July August September 1962

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

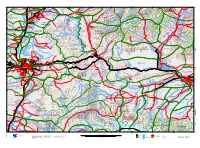

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

Misuse of Licit Trade for Opiate Trafficking in Western and Central

MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA A Threat Assessment A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2012 MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Afghan Opiate Trade Project of the Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA), within the framework of UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and in Pakistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions that shared their knowledge and data with the report team including, in particular, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan, the Ministry of Counter Narcotics of Afghanistan, the customs offices of Afghanistan and Pakistan, the World Customs Office, the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Centre, the Customs Service of Tajikistan, the Drug Control Agency of Tajikistan and the State Service on Drug Control of Kyrgyzstan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Programme management officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Natascha Eichinger (Consultant) Platon Nozadze (Consultant) Hayder Mili (Research expert, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Yekaterina Spassova (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Hamid Azizi (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Shaukat Ullah Khan (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) A. -

Nation Building Process in Afghanistan Ziaulhaq Rashidi1, Dr

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: Saudi J Humanities Soc Sci ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) | ISSN 2415-6248 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: http://scholarsmepub.com/sjhss/ Original Research Article Nation Building Process in Afghanistan Ziaulhaq Rashidi1, Dr. Gülay Uğur Göksel2 1M.A Student of Political Science and International Relations Program 2Assistant Professor, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey *Corresponding author: Ziaulhaq Rashidi | Received: 04.04.2019 | Accepted: 13.04.2019 | Published: 30.04.2019 DOI:10.21276/sjhss.2019.4.4.9 Abstract In recent times, a number of countries faced major cracks and divisions (religious, ethnical and geographical) with less than a decade war/instability but with regards to over four decades of wars and instabilities, the united and indivisible Afghanistan face researchers and social scientists with valid questions that what is the reason behind this unity and where to seek the roots of Afghan national unity, despite some minor problems and ethnic cracks cannot be ignored?. Most of the available studies on nation building process or Afghan nationalism have covered the nation building efforts from early 20th century and very limited works are available (mostly local narratives) had touched upon the nation building efforts prior to the 20th. This study goes beyond and examine major struggles aimed nation building along with the modernization of state in Afghanistan starting from late 19th century. Reforms predominantly the language (Afghani/Pashtu) and role of shared medium of communication will be deliberated. In addition, we will talk how the formation of strong centralized government empowered the state to initiate social harmony though the demographic and geographic oriented (north-south) resettlement programs in 1880s and how does it contributed to the nation building process. -

Yearbook Peace Processes.Pdf

School for a Culture of Peace 2010 Yearbook of Peace Processes Vicenç Fisas Icaria editorial 1 Publication: Icaria editorial / Escola de Cultura de Pau, UAB Printing: Romanyà Valls, SA Design: Lucas J. Wainer ISBN: Legal registry: This yearbook was written by Vicenç Fisas, Director of the UAB’s School for a Culture of Peace, in conjunction with several members of the School’s research team, including Patricia García, Josep María Royo, Núria Tomás, Jordi Urgell, Ana Villellas and María Villellas. Vicenç Fisas also holds the UNESCO Chair in Peace and Human Rights at the UAB. He holds a doctorate in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford, won the National Human Rights Award in 1988, and is the author of over thirty books on conflicts, disarmament and research into peace. Some of the works published are "Procesos de paz y negociación en conflictos armados” (“Peace Processes and Negotiation in Armed Conflicts”), “La paz es posible” (“Peace is Possible”) and “Cultura de paz y gestión de conflictos” (“Peace Culture and Conflict Management”). 2 CONTENTS Introduction: Definitions and typologies 5 Main Conclusions of the year 7 Peace processes in 2009 9 Main reasons for crises in the year’s negotiations 11 The peace temperature in 2009 12 Conflicts and peace processes in recent years 13 Common phases in negotiation processes 15 Special topic: Peace processes and the Human Development Index 16 Analyses by countries 21 Africa a) South and West Africa Mali (Tuaregs) 23 Niger (MNJ) 27 Nigeria (Niger Delta) 32 b) Horn of Africa Ethiopia-Eritrea 37 Ethiopia (Ogaden and Oromiya) 42 Somalia 46 Sudan (Darfur) 54 c) Great Lakes and Central Africa Burundi (FNL) 62 Chad 67 R. -

Governance and Militancy in Pakistan's Kyber Agency

December 2011 1 Governance and Militancy in Pakistan’s Khyber Agency Mehlaqa Samdani Introduction and Background In mid-October 2011, thousands of families were fleeing Khyber, one of the seven tribal agencies in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), to refugee camps or relatives living outside of FATA. Their flight was in response to the announcement by the Pakistani military that it was undertaking a fresh round of operations against militant groups operating in the area. Militants have been active in Khyber (and FATA more generally) for several years. Some have used the area as a safe haven, resting between their own military operations in Afghanistan or other parts of Pakistan. Others have competed locally for influence by providing justice or security services, by decrying the ruling elite’s failure to provide these and other services to the local population, or by using force against those people the militants consider threatening or un-Islamic. The Pakistani military’s actions against militants in Khyber have already driven most of these nonstate groups out of the more populated areas and into Khyber’s remote Tirah Valley. But beyond that, the government of Pakistan has failed to implement most of the legal and political changes required to reform Khyber’s dysfunctional governance system to meet the needs of its residents. Khyber Agency is home to some half-million people, all of whom are ethnic Pashtuns from four major tribal groupings: Afridi, Shinwari, Mullagori, and Shalmani. It is also home to the historic Khyber Pass (to Afghanistan’s Nangarhar Province). Khyber Agency covers an area of 2,576 square kilometers, with Mohmand Agency to the north, the district of Peshawar to the east, Orakzai Agency to the south, and Kurram Agency to the west. -

Afghanistan Topographic Maps with Background (PI42-07)

Sufikhel # # # # # # # # # # # ChayelGandawo Baladeh # Ashorkhel Khwaja-ghar Karak # Kashkha Kawdan Kotale Darrahe Kalan Dasht # Chaharmaghzdara # Eskenya # Zekryakhe# l Korank # # # # Zabikhel # # Qal'a Safed # Khwaja Ahmad # Matan # # # # Ofyane Sharif # # Abdibay # # # Koratas # Wayar # # # Margar Baladeh Walikhel # Tawachyan # Zaqumi# Tayqala Balaghel Qal'a Mirza # Tarang Sara # # Mangalpur Qala Faqirshah # # # # # # Aghorsang Gyawa-i-Payan # # # Darrahe Estama Charikar # # Darrah Kalan Mirkhankhel # # Dadokhel# # Ghazibikhel Dehe-Qadzi # Sedqabad(Qal'a Wazir) Kalawut # # Paytak Nilkhan Dolana Alikhel # Pasha'i Tauskhel # # # # # # # Dehe Babi Y Sherwani Bala # # # Gulghundi # Sayadan Jamchi # Angus # # Tarwari Lokakhel # # # # Jolayan Baladeh # Sharuk # # # # Y # Karezak Bagi Myanadeh # Khwaja Syarane Ulya Dashte Ofyan Bayane Pain Asorkhel Zwane # Dinarkhel Kuhnaqala # Dosti # # # Hazaraha # Sherwani Paya# n Pash'i# Hasankhankhel Goshadur # 69°00' # 10' Dehe Qadzi 20' # 30' 40' 50' 70°00' 10' # Sama2n0d' ur 70# °30' Mirkheli # Sharif Khel # # # iwuh # # Daba 35°00' # # # # 35°00' Zargaran # Qaracha Qal'eh-ye Naw # # Kayli # Pashgar # Ny# azi # Kalacha # Pasha'i # Kayl Daba # # # # # # Paryat Gamanduk # Sarkachah Jahan-nema # # Sadrkhel Yakhel Ba# ltukhel # # # Bebakasang # # # # # # Qoroghchi Badamali # # Qal'eh-ye Khwajaha Qal`eh-ye Khanjar Hosyankhankhel # Odormuk # Mayimashkamda # Sayad # # # # NIJRAB # # Khanaha-i-Gholamhaydar Topdara # Babakhel Kharoti Kundi # Woturu # # Tokhchi # # # Qal`eh-ye Khanjar Sabat Nawjoy # # # Dugran -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Air Operations Are on the Rise As the Air Force Disperses Throughout Afghanistan to Take the Fight to the Enemy

Air operations are on the rise as the Air Force disperses throughout Afghanistan to take the fight to the enemy. Boom Time in Afghanistan fghanistan’s Paktika prov- as the contrails of tankers occasionally in the thick of insurgent and Taliban ince lies due south of the crossed the mountain-studded landscape territory. Concurrently, the metrics for capital Kabul by just over and low flying fighter aircraft crossed US and coalition airpower reflect an 100 miles, over moun- the plains in between. intense fight. In 2008, Air Forces Central Atainous and rugged terrain, abutting Now closing in on its 10th year, the recorded 20,359 close air support sorties, Pakistan’s border to the east. There are war in Afghanistan is flaring anew. but in 2010, AFCENT flew 33,679 CAS few paved roads, but in early March An infusion of troops and resources is missions. In addition, with the arrival there was plenty of traffic high above, placing American and coalition troops of Gen. David H. Petraeus, US Forces Two Army Chinook helicopters lift off on a mission from Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, behind an F-15E Strike Eagle deployed from Sey- mour Johnson AFB, N.C. Bagram, located north of Kabul, has expand- ed significantly since the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom in 2001, as a large number of close air support, airlift, and supply sorties originate from, or route through, the airfield every week. 28 AIR FORCE Magazine / June 2011 Boom Time in Afghanistan By Marc V. Schanz, Senior Editor Afghanistan commander, in July 2010, US and coalition forces entering con- nearly daily clearance and interdiction sorties with weapons releases began tested areas—and staying. -

Great Game to 9/11

Air Force Engaging the World Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland COVER Aerial view of a village in Farah Province, Afghanistan. Photo (2009) by MSst. Tracy L. DeMarco, USAF. Department of Defense. Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland Washington, D.C. 2014 ENGAGING THE WORLD The ENGAGING THE WORLD series focuses on U.S. involvement around the globe, primarily in the post-Cold War period. It includes peacekeeping and humanitarian missions as well as Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom—all missions in which the U.S. Air Force has been integrally involved. It will also document developments within the Air Force and the Department of Defense. GREAT GAME TO 9/11 GREAT GAME TO 9/11 was initially begun as an introduction for a larger work on U.S./coalition involvement in Afghanistan. It provides essential information for an understanding of how this isolated country has, over centuries, become a battleground for world powers. Although an overview, this study draws on primary- source material to present a detailed examination of U.S.-Afghan relations prior to Operation Enduring Freedom. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government. Cleared for public release. Contents INTRODUCTION The Razor’s Edge 1 ONE Origins of the Afghan State, the Great Game, and Afghan Nationalism 5 TWO Stasis and Modernization 15 THREE Early Relations with the United States 27 FOUR Afghanistan’s Soviet Shift and the U.S. -

Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION BOARD REPORT E-11A, T/N 11-9358 430TH EXPEDITIONARY ELECTRONIC COMBAT SQUADRON 455TH AIR EXPEDITIONARY WING BAGRAM AIRFIELD, AFGHANISTAN LOCATION: GHAZNI PROVINCE, AFGHANISTAN DATE OF ACCIDENT: 27 JANUARY 2020 BOARD PRESIDENT: BRIG GEN CRAIG BAKER Conducted IAW Air Force Instruction 51-307 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION E-11A, T/N 11-9358 GHAZNI PROVINCE, AFGHANISTAN 27 JANUARY 2020 On 27 January 2020, at approximately 1309 hours local time (L), an E-11A, tail number (T/N) 11- 9358, was destroyed after touching down in a field in Ghanzi Province, Afghanistan (AFG) following a catastrophic left engine failure. The mishap crew (MC) were deployed and assigned to the 430th Expeditionary Electronic Combat Squadron (EECS), Kandahar Airfield (KAF), AFG. The MC consisted of mishap pilot 1 (MP1) and mishap pilot 2 (MP2). The mission was both a Mission Qualification Training – 3 (MQT-3) sortie for MP2 and a combat sortie for the MC, flown in support of Operation FREEDOM’S SENTINEL. MP1 and MP2 were fatally injured as a result of the accident, and the Mishap Aircraft (MA) was destroyed. At 1105L, the MA departed KAF. The mission proceeded uneventfully until the left engine catastrophically failed one hour and 45 minutes into the flight (1250:52L). Specifically, a fan blade broke free causing the left engine to shutdown. The MC improperly assessed that the operable right engine had failed and initiated shutdown of the right engine leading to a dual engine out emergency. Subsequently, the MC attempted to fly the MA back to KAF, approximately 230 nautical miles (NM) away. -

JPRSS-Vol-02-No-02-Winter-2015.Pdf

JPRSS, Vol. 02, No. 02, Winter 2015 JOURNAL OF PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES Prof. Dr. Naudir Bakht Editor In-Chief It is a matter of great honor and dignity for me and my team that by your (National and International) fabulous and continuous cooperation we are able to present our Research Journal, “Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences, Vol. 2, No.2, Winter 2015, is in your hands. The Center has made every effort to improve the quality and standard of the paper, printing and of the matter. I feel honored to acknowledge your generous appreciation input and response for the improvement of the Journal. I offer my special thanks to 1. Prof. Dr. Neelambar Hatti, Professor Emeritus, Department of Economic History, Lund University, Sweden. 2. Prof. Dr. Khalid Iraqi Dean Public Administration University of Karachi-Karachi 3. Vice Chancellor City University of Science and Information Technology Dalazak Road-Peshawar 4. Prof. Dr. Faizullah Abbasi Vice Chancellor Dawood University of Engineering and Technology M.A. Jinnah Road, Karachi 5. Prof. Dr. Rukhsana David Principal Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences JPRSS, Vol. 02, No. 02, Winter 2015 Kinnaird College for Women Lahore 6. Prof. Dr. Parveen Shah Vice Chancellor Shah Abdul Latif University Khair Pur-Sindh 7. Engr. Prof. Dr. Sarfraz Hussain, TI(M), SI(M) Vice Chancellor DHA SUFA UNIVERSITY DHA, Karachi 8. Vice Chancellor University of Agriculture Faisal Abad 9. Vice Chancellor SZABIST-Islamabad Campus H-8/4, IslamAbad 10. Vice Chancellor Dr. Abdul Salam Ganghara University, Canal road-Peshawar 11. Vice Chancellor, Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad. -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision.