The Curious Cat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abyssinian Cat Club Type: Breed

Abyssinian Cat Association Abyssinian Cat Club Asian Cat Association Type: Breed - Abyssinian Type: Breed – Abyssinian Type: Breed – Asian LH, Asian SH www.abycatassociation.co.uk www.abyssiniancatclub.com http://acacats.co.uk/ Asian Group Cat Society Australian Mist Cat Association Australian Mist Cat Society Type: Breed – Asian LH, Type: Breed – Australian Mist Type: Breed – Australian Mist Asian SH www.australianmistcatassociation.co.uk www.australianmistcats.co.uk www.asiangroupcatsociety.co.uk Aztec & Ocicat Society Balinese & Siamese Cat Club Balinese Cat Society Type: Breed – Aztec, Ocicat Type: Breed – Balinese, Siamese Type: Breed – Balinese www.ocicat-classics.club www.balinesecatsociety.co.uk Bedford & District Cat Club Bengal Cat Association Bengal Cat Club Type: Area Type: PROVISIONAL Breed – Type: Breed – Bengal Bengal www.thebengalcatclub.com www.bedfordanddistrictcatclub.com www.bengalcatassociation.co.uk Birman Cat Club Black & White Cat Club Blue Persian Cat Society Type: Breed – Birman Type: Breed – British SH, Manx, Persian Type: Breed – Persian www.birmancatclub.co.uk www.theblackandwhitecatclub.org www.bluepersiancatsociety.co.uk Blue Pointed Siamese Cat Club Bombay & Asian Cats Breed Club Bristol & District Cat Club Type: Breed – Siamese Type: Breed – Asian LH, Type: Area www.bpscc.org.uk Asian SH www.bristol-catclub.co.uk www.bombayandasiancatsbreedclub.org British Shorthair Cat Club Bucks, Oxon & Berks Cat Burmese Cat Association Type: Breed – British SH, Society Type: Breed – Burmese Manx Type: Area www.burmesecatassociation.org -

Feral and Free Ranging Domestic Cats

No. 306 THE WILDLIFER Page 57 FERAL AND FREE-RANGING DOMESTIC CATS Position Statement Free and free-ranging domestic cats are exotic species to North America. Exotic species are recognized as one of the most widespread and serious threats to the integrity of native wildlife populations and natural ecosystems. Exotic species present special challenges for wildlife managers because their negative impacts are poorly understood by the general public, many exotic species have become such an accepted component of the envirom- nent that many people regard them as "natural," some exotic species have advocacy groups that promote their continued presence, and few policies and laws deal directly with their control. Perhaps no issue has captured more of the challenges for contemporary wildlife management than the impacts of feral or free-ranging human companion or domestic animals. The domestic cat is the companion animal that recently has attracted the most attention for its impact on wildlife species. Domestic cats originated from an ancestral wild species, the European and African wild cat (Felis silvestris). The domestic cat (Felis catus) is now considered a separate species. The estimated numbers of pet cats in urban and rural regions of the United States have grown from 30 million in 1970 to nearly 65 million in 2000. Reliable estimates of the present total cat population are not available. Nationwide, approximately 30% of households have cats. In rural areas, approximately 60% of households have cats. The impact of domestic cats on wildlife is difficult to quantify. However, a growing body of literature strongly suggests that domestic cats are a significant factor in the mortality of small mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. -

Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat

UPTEC X 12 012 Examensarbete 30 hp Juni 2012 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Molecular Biotechnology Programme Uppsala University School of Engineering UPTEC X 12 012 Date of issue 2012-06 Author Carolin Johansson Title (English) Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Title (Swedish) Abstract This study presents mitochondrial genome sequences from 22 Egyptian house cats with the aim of resolving the uncertain origin of the contemporary world-wide population of Domestic cats. Together with data from earlier studies it has been possible to confirm some of the previously suggested haplotype identifications and phylogeny of the Domestic cat lineage. Moreover, by applying a molecular clock, it is proposed that the Domestic cat lineage has experienced several expansions representing domestication and/or breeding in pre-historical and historical times, seemingly in concordance with theories of a domestication origin in the Neolithic Middle East and in Pharaonic Egypt. In addition, the present study also demonstrates the possibility of retrieving long polynucleotide sequences from hair shafts and a time-efficient way to amplify a complete feline mitochondrial genome. Keywords Feline domestication, cat in ancient Egypt, mitochondrial genome, Felis silvestris libyca Supervisors Anders Götherström Uppsala University Scientific reviewer Jan Storå Stockholm University Project name Sponsors Language Security English Classification ISSN 1401-2138 Supplementary bibliographical information Pages 123 Biology Education Centre Biomedical Center Husargatan 3 Uppsala Box 592 S-75124 Uppsala Tel +46 (0)18 4710000 Fax +46 (0)18 471 4687 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning Det är inte sedan tidigare känt exakt hur, när och var tamkatten domesticerades. -

Home Range Size, Habitat Utilisation and Movement Patterns of Suburban and Farm Cats Felis Catus

ECOGRAPHY 20: 271-280. Copenhagen 1997 Home range size, habitat utilisation and movement patterns of suburban and farm cats Felis catus David G. Barratt Bdrratt, D G 1997 Home range size, habitat utilisation and movement patterns of suburban and farm cats Felts caius - Ecography 20 271-280 The movements of 10 house cats (4 desexed females, 5 desexed males and 1 intact male) living on the edge of a suburb adjoining grassland and forest/woodland habitat, and a neighbounng colony of seven farm cats, were examined using radio-telemetry over nine months Nocturnal home range areas of the suburban cats vaned between 0 02 and 27 93 ha (mean 7 89 ha), and were larger than diumal home range areas (range 0 02 to 17 19 ha - mean 2 73 ha) Nocturnal home range areas of cats from the farm cat colony vaned between 1 38 and 4 46 ha (mean 2 54 ha), and were also larger than diumal home range areas (range 0 77 to 3 70 ha - mean 1 70 ha) Home ranges of cats in the farm cat colony overlapped extensively, as did those of cats living at the same suburban residence There was no overlap of home ranges of female cats from different residences, and little overlap between males and females from different residences Four of the suburban house cats moved between 390 m and 900 m into habitat adjoining the suburb Polygons descnbing the home ranges of these animals were strongly spatially biased away from the suburban environment, though the cats spent the majonty of their time within the bounds of the suburb Movements further than 100-200 m beyond the suburb edge were -

Missing Cats, Stray Coyotes: One Citizen’S Perspective

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Proceedings for 4-1-2007 MISSING CATS, STRAY COYOTES: ONE CITIZEN’S PERSPECTIVE Judith C. Webster Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_wdmconfproc Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Webster, Judith C., "MISSING CATS, STRAY COYOTES: ONE CITIZEN’S PERSPECTIVE" (2007). Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Proceedings. 78. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_wdmconfproc/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Missing Cats, Stray Coyotes: One Citizen’s Perspective * Judith C. Webster , Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Abstract : The author explores the issue of urban coyotes and coyote management from a cat owner’s perspective, with specific examples from Vancouver, B.C., Canada. Following a personal encounter with two coyotes in July 2005 that led to the death of a cat, the author has delved into the history of Vancouver’s “Co-existing with Coyotes”, a government-funded program run by a non- profit ecological society. The policy’s roots in conservation biology, the environmental movement, and the human dimensions branch of wildlife management are documented. The author contends that “Co-existing with Coyotes” puts people and pets at greater risk of attack by its inadequate response to habituated coyotes, and by an educational component that misrepresents real dangers and offers unworkable advice. -

Printable Breed Introduction

TICA Khaomanee Breed Introduction www.tica.org General Description: With one blue eye and one eye ranging from copper through yellow to green, this shining white cat from Thailand captures the imagination. Khaomanee (sometimes seen as Khao Manee) means White Gem and is thought to have been a favorite in the royal palaces. A heart- shaped face with high cheekbones and a brilliant white coat like diamonds belie the naughtiness of these stunning cats, but their devotion to you will have you admiring the naughtiness that these intelligent cats so enjoy as they entertain you with their antics. History: Several related breeds have their origins, ancient origins, in Thailand. The Siamese (Wichien-maat), the Burmese (Suphalak), the Korat (Dork Lao) and the Khaomanee. The first three breeds are well-established in the West but the Khaomanee has remained a well-kept secret in its native Thailand. Like the other breeds, we find references to the Khaomanee in the Tamra Maew (an ancient collection of Thai cat poems from 1350). Although in that text, it is called the Khao Plort. While the eyes were originally referred to as the color of mercury, the eye color was changed to reflect the odd-eyed cats that were considered lucky and also to have the yellow eyes like canary diamonds that breeders also favored. Interest in these striking cats has grown in the West, and in 1999, Colleen Freymouth imported the first Khaomanee, Sripia, from Thailand to the US. She also imported a male and bred the first Khaomanee litter in North America. Janet Poulsen (Odyssey cattery) exported the first Khaomanee to the UK, and interest in the breed is growing there, as breeders import more of these stunning cats from Thailand to continue developing the breed. -

Understanding Human Factors Involved in the Unwanted Cat Problem

UNDERSTANDING HUMAN FACTORS INVOLVED IN THE UNWANTED CAT PROBLEM Sarah Jane Maria Zito BVetMed MANZCVS (feline medicine) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 School of Veterinary Science I Abstract The large number of unwanted cats in many modern communities results in a complex, worldwide problem causing many societal issues. These include ethical concerns about the euthanasia of many healthy animals, moral stress for the people involved, financial costs to organisations that manage unwanted cats, environmental costs, wildlife predation, potential for disease spread, community nuisance, and welfare concerns for cats. Humans contribute to the creation and maintenance of unwanted cat populations and also to solutions to alleviate the problem. The work in this thesis explored human factors contributing to the unwanted cat problem—including cat ownership perception, cat caretaking, cat semi-ownership and cat surrender—and human factors associated with cat adoption choices and outcomes. To investigate human factors contributing to the unwanted cat problem, data were collected from 141 people surrendering cats to four animal shelters. The aim was to better understand the people and human-cat relationships involved, and ultimately to inform strategies to reduce shelter intake. Participants were recruited for this study when they surrendered a cat to a shelter and information was obtained on their demographics, cat interaction history, cat caretaking, and surrender reasons. This information was used to describe and compare the people, cats, and human-cat relationships contributing to shelter intake, using logistic regression models and biplot visualisation techniques. A model of cat ownership perception in people that surrender cats to shelters was proposed. -

PDF Download the Cat Ebook, Epub

THE CAT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ella Earle | 96 pages | 01 Apr 2012 | Summersdale Publishers | 9781849531429 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom The Cat PDF Book It is noteworthy that the ancestors of the other common household pet , the dog , were social animals that lived together in packs in which there was subordination to a leader, and the dog has readily transferred its allegiance from pack leader to human master. Although the origin of the domesticated cat is hidden in antiquity, studies involving mitochondrial DNA mtDNA suggest that there have been two lineages of Felis catus. Table Of Contents. She tells them that if they want to leave, then they must get a combined score of points, but they have an opponent. He helped her tremendously by giving Coraline the last ghost eye when she thought that she lost the game. Michael W. Take the quiz Forms of Government Quiz Name that government! For an account of the relationship of the family of cats to other carnivores, see carnivore. Company Credits. Wall tiles in Crete dating from bce depict hunting cats. Added to Watchlist. External Reviews. The ancestry of Persian and Siamese cats may well be distinct from that of other domestic breeds, representing a domestication of an Asian wild cat. They first appeared in the early Pliocene Epoch 5. He seems to understand the nature of the other world in full detail, including its history and the terrible truth behind its facade. Book 5. Accessed 21 Oct. Throughout the ages, cats have been more cruelly mistreated than perhaps any other animal. Samantha is a shrewd business-cat, always looking for opportunities to collect unique things and make sales, even of entirely useless items. -

The British Ragdoll Cat Club 5 January 2013. The

THE BRITISH RAGDOLL CAT CLUB 5 TH JANUARY 2013. THE KORAT & THAI CAT ASSOCIATION SHORTHAIR CAT SOCIETY SHEILA P HAMILTON © A very busy and a very enjoyable event staged by seven clubs/societies/associations providing excellent organisation on the part of all concerned. LINDA ASHMORE the Show Manager was in her usual competent and efficient mode as she bustled about. It was good to see her looking so well again. I spent the majority of my day in the Ragdoll section and will therefore report on this show first. Congratulations to PAULA LONG and to her Assistants KAREN HARNELL and MARGARET WALKDEN- all their hard work paid off and their organisation and hospitality left nothing to be desired. My day was made complete by having the very good company of an excellent steward MARGARET LYNCH who handled the cats with expertise and dedication. Thank you Margaret, I look forward to next time My very enjoyable day was made complete by judging the overall Best in Show with a lovely line up of the cream of the Ragdoll Breed. My overall winner was a superb representative of the breed - a very handsome neuter boy with presence owned by MRS M.PENMAN PR DIZZIPAWS ROBERTO 66AW .He showed excellent type throughout with a superb temperament and was beautifully prepared and presented. Congratulations to both ROBERTO and his very happy owner on their successful day. OLYMPIAN CLASS A.C OR PATTERNED IMPERIAL GRAND CHAMPION MALE ( 2 ENTERED) 1ST & OLYMPIAN CERT TO HAWORTH UK & IMP GR CH DIZZIPAWS BRUCE 66 MALE 2/8/06 A very handsome and masculine boy showing excellent classic type to his strong and broad head with excellent top and flat plane. -

RBBA Schedule

Russian Blue Breeders’ Association (A Non-Profit making organisation) Schedule of the 32nd CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW (Held Under The Rules And Licence Of The GCCF) At the Bugbrooke Community Centre Camp Close, Bugbrooke, NN7 3RW on Saturday, 7th October 2017 th Entries close on 16 September 2017 Joint Show Managers Mrs Marlene Buckeridge Stari House, Leeds Road, Langley Heath, Maidstone, Kent, ME17 3JG Tel: 01622 861176 e-mail: [email protected] Mrs Anne Murray-Brooks The Rowans, 128 Barnham Road, Barnham, West Sussex. PO22 0EH Tel: 01243 555222 email [email protected] All Entries to Mrs A. Murray-Brooks Proudly Sponsored By 1 Russian Blue Breeders’ Association OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE 2017 President: MR T TURNER, B.Vet.Med., M.R.C.V.S. Vice-Presidents: MRS M KIDD, MRS L M TROMPETTO, MRS J. JACKSON Chairman: MRS M BUCKERIDGE Vice-Chairman: MRS J FLEMING Hon. Treasurer: MRS V A ANDERSON Hon. Secretary: MRS C MOORE Hon. Cup Secretary (AGM): Mrs J Noble, 14a Bedford Road Stagsden, Beds, MK43 8TP Hon. Cup Secretary (Show): Mrs J Noble, Manor Farm House, 29, Eaton Rd, Appleton, Abingdon, Oxon, OX13 5JR Hon. Show Support Secretary: Miss C Bandy, 6 Hickman’s Hill, Clothall, Baldock, Herts, SG7 6RH Committee and Show Committee Miss C Bandy, Mrs A Cherry, Mrs C Kaye, Mrs J Noble, Mrs J Oakley, Mrs M Ravenscroft, Mrs S Young Mrs A Murray-Brooks Pedigree Judges: Mrs L Ashmore, Mrs N Johnson, Mrs S Luxford-Watts, Mr S Parkin, Miss E Stark Best in Show Panel: Mrs L Ashmore, Mrs N Johnson, Miss E Stark Overall Best in Show Judge: Mrs Luxford-Watts Non-Pedigree Judges: Mr H Bailey, Mrs G Phillips Best Non-Pedigree & Best Pedigree Pet Mr S Parkin Hon. -

Our Friends for Life! Arizona Reading Program Manual. INSTITUTION Arizona State Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 464 324 CS 510 792 TITLE Books and Pets: Our Friends for Life! Arizona Reading Program Manual. INSTITUTION Arizona State Dept. of Library, Archives and Public Records, Phoenix.; Arizona Humanities Council, Phoenix. SPONS AGENCY National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities, Washington, DC. Inst. of Museum and Library Services. PUB DATE 2002-01-00 NOTE 282p.; CD-ROM is not available from ERIC. A Project of Arizona Reads funded under the Library Services and Technology Act. Creative coordination and design by K-READ. AVAILABLE FROM Arizona Humanities Council, 1242 N. Central Ave., Phoenix, AZ 85004-1887. Tel: 602-257-0335; Fax: 602-257-0392; Web Site: http://azhumanities.org/cat02-03/f-azreading.html. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bibliographies; Childrens Literature; Class Activities; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; Handicrafts; Individual Needs; Learning Activities; Nonfiction; *Pets; Reading Games; *Reading Programs; *State Programs IDENTIFIERS Arizona ABSTRACT This reading program manual delineates the "Books and Pets" program, a project of Arizona Reads, which is a collaboration between the Arizona Humanities Council and the Arizona State Library, Archives, and Public Records. A CD-ROM version of the program accompanies the manual. The manual is divided into the following parts: Introduction; Getting Started (Planning with Goals and Objectives; Program Planning and Scheduling; Let's Get Everyone Involved; Awards and Incentives; Program Survey; Publicity -

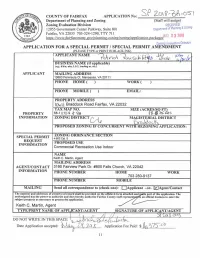

'GC" I Rauisca);- 1' Coi-Iiic ( /1./ A/ BUSINESS NAME (If Applicable) (E.G., D/B/A; Aka; LLC; Trading As, Etc.)

COUNTY OF FAIRFAX APPLICATION No: Department of Planning and Zoning (Staff will assign) Zoning Evaluation Division RECEIVED 12055 Government Center Parkway, Suite 801 Department of Planning & Zoning Fairfax, VA 22035 703-324-1290, TTY 711 https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/planning-zoning/zoning/application-packagesMAY 2 2 2018 Zoning Evaluation Division APPLICATION FOR A SPECIAL PERMIT / SPECIAL PERMIT AMENDMENT PLEASE TYPE or PRINT IN BLACK INK) I APPLICANT NAME 'GC" i RauiSCA);- 1' coi-iiiC ( /1./ A/ BUSINESS NAME (if applicable) (e.g., d/b/a; aka; LLC; trading as, etc.) APPLICANT MAILING ADDRESS 10860 Peninsula Ct. Manassas, VA 20111 PHONE HOME ( ) WORK ( ) PHONE MOBILE ( ) EMAIL: PROPERTY ADDRESS INI i Braddock Road Fairfax, VA 22032 TAX MAP NO. SIZE (ACRES/SQ FT) PROPERTY 68-1 (CI )) 9 4- WI MS f- 12,e5 INFORMATION ZONING DISTRICT eAc MAGISTERIAL DISTRICT PROPOSED ZONING IF CONCURRENT WITH REZONING APPLICATION: ZONING ORDINANCE SECTION SPECIAL PERMIT 4-603 CM. 5 REQUEST PROPOSED USE INFORMATION Commercial Recreation Use Indoor NAME Keith C. Martin, Agent MAILING ADDRESS AGENT/CONTACT 3190 Fairview Park Dr. #800 Falls Church, VA 22042 INFORMATION PHONE NUMBER HOME WORK 703 280-9137 PHONE NUMBER MOBILE MAILING Send all correspondence to (check one): ilApplicant —or- LjAgent/Contact The name(s) and addresses of owner(s) of record shall be provided on the affidavit form attached and e part of this application. The undersigned has the power to authorize and does hereby authorize Fairfax County staff represent • s on official business to enter