Home Range Size, Habitat Utilisation and Movement Patterns of Suburban and Farm Cats Felis Catus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feral and Free Ranging Domestic Cats

No. 306 THE WILDLIFER Page 57 FERAL AND FREE-RANGING DOMESTIC CATS Position Statement Free and free-ranging domestic cats are exotic species to North America. Exotic species are recognized as one of the most widespread and serious threats to the integrity of native wildlife populations and natural ecosystems. Exotic species present special challenges for wildlife managers because their negative impacts are poorly understood by the general public, many exotic species have become such an accepted component of the envirom- nent that many people regard them as "natural," some exotic species have advocacy groups that promote their continued presence, and few policies and laws deal directly with their control. Perhaps no issue has captured more of the challenges for contemporary wildlife management than the impacts of feral or free-ranging human companion or domestic animals. The domestic cat is the companion animal that recently has attracted the most attention for its impact on wildlife species. Domestic cats originated from an ancestral wild species, the European and African wild cat (Felis silvestris). The domestic cat (Felis catus) is now considered a separate species. The estimated numbers of pet cats in urban and rural regions of the United States have grown from 30 million in 1970 to nearly 65 million in 2000. Reliable estimates of the present total cat population are not available. Nationwide, approximately 30% of households have cats. In rural areas, approximately 60% of households have cats. The impact of domestic cats on wildlife is difficult to quantify. However, a growing body of literature strongly suggests that domestic cats are a significant factor in the mortality of small mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. -

Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat

UPTEC X 12 012 Examensarbete 30 hp Juni 2012 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Molecular Biotechnology Programme Uppsala University School of Engineering UPTEC X 12 012 Date of issue 2012-06 Author Carolin Johansson Title (English) Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Title (Swedish) Abstract This study presents mitochondrial genome sequences from 22 Egyptian house cats with the aim of resolving the uncertain origin of the contemporary world-wide population of Domestic cats. Together with data from earlier studies it has been possible to confirm some of the previously suggested haplotype identifications and phylogeny of the Domestic cat lineage. Moreover, by applying a molecular clock, it is proposed that the Domestic cat lineage has experienced several expansions representing domestication and/or breeding in pre-historical and historical times, seemingly in concordance with theories of a domestication origin in the Neolithic Middle East and in Pharaonic Egypt. In addition, the present study also demonstrates the possibility of retrieving long polynucleotide sequences from hair shafts and a time-efficient way to amplify a complete feline mitochondrial genome. Keywords Feline domestication, cat in ancient Egypt, mitochondrial genome, Felis silvestris libyca Supervisors Anders Götherström Uppsala University Scientific reviewer Jan Storå Stockholm University Project name Sponsors Language Security English Classification ISSN 1401-2138 Supplementary bibliographical information Pages 123 Biology Education Centre Biomedical Center Husargatan 3 Uppsala Box 592 S-75124 Uppsala Tel +46 (0)18 4710000 Fax +46 (0)18 471 4687 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning Det är inte sedan tidigare känt exakt hur, när och var tamkatten domesticerades. -

Missing Cats, Stray Coyotes: One Citizen’S Perspective

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Proceedings for 4-1-2007 MISSING CATS, STRAY COYOTES: ONE CITIZEN’S PERSPECTIVE Judith C. Webster Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_wdmconfproc Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Webster, Judith C., "MISSING CATS, STRAY COYOTES: ONE CITIZEN’S PERSPECTIVE" (2007). Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Proceedings. 78. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_wdmconfproc/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Missing Cats, Stray Coyotes: One Citizen’s Perspective * Judith C. Webster , Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Abstract : The author explores the issue of urban coyotes and coyote management from a cat owner’s perspective, with specific examples from Vancouver, B.C., Canada. Following a personal encounter with two coyotes in July 2005 that led to the death of a cat, the author has delved into the history of Vancouver’s “Co-existing with Coyotes”, a government-funded program run by a non- profit ecological society. The policy’s roots in conservation biology, the environmental movement, and the human dimensions branch of wildlife management are documented. The author contends that “Co-existing with Coyotes” puts people and pets at greater risk of attack by its inadequate response to habituated coyotes, and by an educational component that misrepresents real dangers and offers unworkable advice. -

Understanding Human Factors Involved in the Unwanted Cat Problem

UNDERSTANDING HUMAN FACTORS INVOLVED IN THE UNWANTED CAT PROBLEM Sarah Jane Maria Zito BVetMed MANZCVS (feline medicine) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 School of Veterinary Science I Abstract The large number of unwanted cats in many modern communities results in a complex, worldwide problem causing many societal issues. These include ethical concerns about the euthanasia of many healthy animals, moral stress for the people involved, financial costs to organisations that manage unwanted cats, environmental costs, wildlife predation, potential for disease spread, community nuisance, and welfare concerns for cats. Humans contribute to the creation and maintenance of unwanted cat populations and also to solutions to alleviate the problem. The work in this thesis explored human factors contributing to the unwanted cat problem—including cat ownership perception, cat caretaking, cat semi-ownership and cat surrender—and human factors associated with cat adoption choices and outcomes. To investigate human factors contributing to the unwanted cat problem, data were collected from 141 people surrendering cats to four animal shelters. The aim was to better understand the people and human-cat relationships involved, and ultimately to inform strategies to reduce shelter intake. Participants were recruited for this study when they surrendered a cat to a shelter and information was obtained on their demographics, cat interaction history, cat caretaking, and surrender reasons. This information was used to describe and compare the people, cats, and human-cat relationships contributing to shelter intake, using logistic regression models and biplot visualisation techniques. A model of cat ownership perception in people that surrender cats to shelters was proposed. -

The Behaviour of the Domestic Cat, Second Edition

12 Physiological and Pathological Causes of Behavioural Change Introduction Overt behaviour is the consequence of a cat perceiving some change in its environment, evaluating this change, deciding on an appropriate response and the response being generated through the motor systems of the brain to the elements of the skeletal system that control activity. Hence, although behaviour occurs as a consequence of changes in the external environment, the responses generated also depend on internal variations in the processing of information. These processes are susceptible to alteration due not only to normal physiological variations but also to pathological changes. Interpretation of behaviour, therefore, requires an understanding of how the generation of behaviour is modulated by factors influencing the internal state, as well as how responses are generated to events in the external environment. Pathological changes can be the sole cause of behavioural change – indeed, behavioural signs such as lameness are common first indicators of disease in veterinary medicine. In some cases complex behavioural signs, such as aggressive behaviour towards an owner, can occur entirely as a consequence of pathological events, such as focal seizures. Although such events are rare, their characteristics need to be distinguished from behaviours generated in response to external stimuli when investigating the cause of undesired behaviours. However, physiological or pathological changes more commonly modify cats’ behaviour rather than solely cause it. This is through alterations in one or more of the following: (i) perception of external events; (ii) the motivation to show a response; (iii) the threshold at which a response is shown; and (iv) the manner in which a response is generated. -

Barn Cats-Part 1

Cats International What are Barn Cats? Generally NOT Cared For - Victims Vulnerable to People - Generally Not Well Cared For - Sickly - Work for Little Pay UNDERSTANDING WHAT BARN CATS REALLY NEED Table of contents: What Is A Barn Cat? ………………………………………………. 1-6 How to Care for A Barn Cat …………………………………… 7 If Relocation is Necessary ……………………………………… 8-13 Explained Barn Cat Behavior …………………………………. 14-16 The Barn Cat Is a Great Asset ………………………………… 17 What Is A Barn Cat? A Happy Healthy Neutered Barn Cat Every circumstance is quite the same. You buy a farm with a barn, already present are the faces of hungry cats and kittens looking to call the barn still their home. People sell or leave the farm with all animals taken except the cats. Most farm cats possess no worth to people. People seem to love the fact that cats will keep the area rodent free, still they are considered a nuisance and not cared for or wanted. They seem to just show up as soon as you turn on a light or show any sign of activity in the barn. More than likely, they have lived there before you did. Most people view the barn/farm cat as a disposable animal that has no worth. Quite the opposite, they are worth their weight in gold. They rid your barn and farm from varmints that can make your farm an unhealthy place for other animals and yourself. 1 Given the respect they deserve, spay or neutered and a clean safe environment to work from, food, water and shelter from the elements outside, they will earn and prove just how dedicated and valuable they can become to any size of barn or farm. -

Madison County, IL Code of Ordinances

Madison County, IL Code of Ordinances - ANIMALS Section General Provisions 50.001 Short title 50.002 Definitions 50.003 Animal Control Program Administration 50.015 Administrator 50.016 Personnel and facilities 50.017 Funding 50.018 Authorization for requiring registration 50.019 Duties 50.020 Police power; cooperation of Police Department 50.021 Causes for removal of Administrator from office 50.022 Inspections; entry 50.023 Fees for registration of dogs and cats 50.024 Fees for registration of litters Impoundment 50.040 Impoundment 50.041 Registration of impounded dogs and cats 50.042 Notice of impoundment 50.043 Redemption of impounded animal; conditions for redemption 50.044 Animals not redeemed 50.045 Release without spaying or neutering prohibited 50.046 Humane societies exempt 50.047 Payment for rabies inoculation 50.048 Notice of picking up or confining strays to pound 50.049 Dogs and cats in heat Reporting and Confinement After Biting 50.060 Confinement of animal after reported bite 50.061 Veterinarian to examine and report to Administrator 50.062 Confinement in owner’s house 50.063 Post-confinement examination of dog 50.064 Noncompliance; violations 50.065 Confinement period for animal which has bitten a person 50.066 Bite reporting and investigation 50.067 Sterilization of biting animals Vicious and Dangerous Dogs 50.080 Enforcement and authorization 50.081 Dangerous dogs 50.082 Control methods for dangerous dogs 50.083 Vicious dogs 50.084 Microchip identification of dangerous and vicious dogs 50.085 Appeals 50.086 Exemptions -

Truth About Cats and Dogs

Everybody wants to be a cat Bengal Cat Siberian Cat Savanah Cat Siamese Cat Sphinx Cat Russian Blue Memories Big Ear Cat . One of the most popular breeds of cat in the USA, this short-haired breed has the old name for the country where it was thought to have originated. Which fine-boned, slender, medium-sized breed of cat is this? Abyssinian Abyssinian • Although this breed was developed in Great Britain, it was given the old name for what is now Ethiopia/Abyssinia. • It was thought the breed developed from kittens brought home by returning soldiers coming from that part of the world. • There is an element of truth in the story but, it now seems that the soldiers almost certainly bought their kittens from Egyptian traders, rather than Ethiopian ones. Indeed, recent research suggests that the breed may have developed from a single cat, named Zula, bought by a soldier in Alexandria in 1868. • This breed is sometimes called a "Purebred Long-haired Siamese", since is developed as a mutation from the standard Siamese. Noted for its sapphas a light-coloured body with darker extremities. Considered the most intelligent of all long- haired breeds, which cat is this? Bengal Bengal cat • This is a rare breed of domestic cat from France. Large and muscular(called cobby) with relatively short, fine-boned limbs, and very fast reflexes. They are known for their blue (grey) water-resistant short hair double coats and orange or copper-colored eyes. They are also known for their “smile”. These cats are exceptional hunters and are highly prized by farmers. -

North Utah Valley Animal Services: The

NORTH UTAH VALLEY ANIMAL SERVICES SPECIAL SERVICE DISTRICT THE SCIENCE OF FERAL CATS A Research Based Report STEVE ALDER Environmental Health Bureau Director Utah County Health Department TRENT COLLEDGE Lieutenant Orem City Police Department JOSH CHRISTENSEN Lieutenant American Fork Police Department TUG GETTLING Director North Utah Valley Animal Services OWEN JACKSON Assistant City Manager Saratoga Springs CARL NIELSON Sergeant Pleasant Grove Police Department YVETTE RICE Lieutenant Utah County Sheriff’s Office 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….3 2. Best Friends Animal Society Proposal…………………………………………………………………………………..………4 3. Statistical Comparison Brief……………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 4. Addressing Inaccurate Claims…………………………………………………………………………………………………...6 5. Scientific Excerpts by Topic of Concern………………………………………………………………………………………...8 6. Summary of Select Peer-Reviewed Scientific Literature………………………………………………………………………15 7. Subject Matter Expert Statement…………………………………………………………………………………………...…..22 8. Position Statements…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….27 9. Research-based Conclusions……………………………………………………………………………………………...……36 10. Organizations Opposed to TNR Programs………………………………………………………………………………..……37 11. References…………………………………………………………………...…………………………………. ……………..40 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The North Utah Valley Animal Services Special Service District (NUVAS) provides animal sheltering, regulation, care, control, and services for the municipalities that exist within our district -

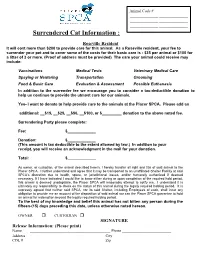

Surrendered Cat Information

Animal Code # _____________ _____________ _____________ _____________ _____________ _____________ Surrendered Cat Information : Roseville Resident It will cost more than $200 to provide care for this animal. As a Roseville resident, your fee to surrender your pet and to cover some of the costs for their basic care is : $35 per animal or $100 for a litter of 3 or more. (Proof of address must be provided) The care your animal could receive may include: Vaccinations Medical Tests Veterinary Medical Care Spaying or Neutering Transportation Grooming Food & Basic Care Evaluation & Assessment Possible Euthanasia In addition to the surrender fee we encourage you to consider a tax-deductible donation to help us continue to provide the utmost care for our animals. Yes- I want to donate to help provide care to the animals at the Placer SPCA. Please add an additional: __$15, __$25, __$50, __$100, or $_________ donation to the above noted fee. Surrendering Party please complete: Fee: $_____________ Donation: $_____________ (This amount is tax deductible to the extent allowed by law.) In addition to your receipt, you will receive an acknowledgment in the mail for your donation. Total: $_____________ As owner, or custodian, of the animal described herein, I hereby transfer all right and title of said animal to the Placer SPCA. I further understand and agree that it may be transported to an unaffiliated Shelter Facility at said SPCA’s discretion due to health, space, or jurisdictional issues, and/or humanely euthanized if deemed necessary. If I have indicated I would like to know either during or upon completion of the required hold period, this animal is deemed unadoptable, the Placer SPCA will reasonably attempt to notify me. -

Overview 1CHAPTER

Overview 1CHAPTER 1.1 Defining the Problem he mere mention of feral cats creates a storm of emotion and con- troversy for many people. Where do feral cats come from? What Tshould be done about them? What is best for them? Who is responsi- ble for them? Although the cats themselves often are at the center of the storm, feral cats are a “people problem.” They are the offspring of outdoor, intact cats—owned or abandoned. They are on farms and in cities, sub- urbs, and wilderness areas. They can be found near schools, restaurants, hospitals, barns, apartments, and abandoned buildings—anywhere there is adequate food and shelter (Mahlow and Slater 1996). Some people feed them, others provide veterinary care; some feel sorry for them but do nothing, others that believe they should be removed and destroyed. Even the veterinary profession is divided on how to view feral cats, as reflected in conflicting and often emotional letters in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (Hughes 1993; DeBrito and Doffermyre 1994; Heerens 1994; Heerens 1996; Gross et al. 1996; McGrath 1996; Patronek 1996). These letters were responses to an article on controlling 1 2 Community Approaches to Feral Cats feral cats through neuter and release (Zaunbrecher and Smith 1993) and a later American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) report on cat wel- fare and overpopulation (Kahler 1996). What is a “feral” cat? For this book, any cat who is too poorly socialized to be handled (and therefore must be trapped or sedated for examination) and who cannot be placed into a typical pet home is feral. -

The Curious Cat

THE CURIOUS CAT Miebael Allaby and Peter Crawford Michael Joseph « London First published in Great Britain by Michael Joseph Limited 44 Bedford Square, London W.C.1 1982 © 1982 by Michael Allaby and Peter Crawford All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means,electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Copyright owner ISBN 0 7181 2065 5 Filmset and printed in Great Britain by BAS Printers Limited, Over Wallop, Hampshire and bound by Hunterand Foulis Ltd., Edinburgh Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Downon the farm 12 Staking out territories 29 Hunting 44 The technology 60 Social life among the cats 72 Whatis a cat? 88 The next generation 104 Learning to be a cat 119 The winter 138 The outside world I§1 Postscript 158 Index 159 Geknowledgements The authorswish to thankthe following for permission to reproduce the photographs usedin this book: Vanellus Productions Ltd., Maurice Tibbles: for those appearing on pages 13, 49, §5, 82, 107 and 118 (right) Radio Times: for those appearing on pages 14, 68, 139 and 144 Peter Apps: for those appearing on pages 20, 36, 41, 42, 46, 97, IIO, 118 (deft), 122, 128, 129, 132, 134 (both), 141 and 143 Peter Crawford took the photographs which appearon the following pages: 16, 17, 21, 25, 27, 33, 50, 64, 65, 127, 136, 148, 153, 155 Boris Weltman drew the endpaper map Introduction EARLYIN 1978,as one of the harshest winters ever knownin that part of the country was promising to turn into a North Devon spring, a small team of people began work in a barn and a hut not far from the Atlantic coast.