Decision Making for Wildfires: a Guide for Applying a Risk Management Process at the Incident Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Reading Smoke for Rapid Decision Making

The Art of Reading Smoke for Rapid Decision Making Dave Dodson teaches the art of reading smoke. This is an important skill since fighting fires in the year 2006 and beyond will be unlike the fires we fought in the 1900’s. Composites, lightweight construction, engineered structures, and unusual fuels will cause hostile fires to burn hotter, faster, and less predictable. Concept #1: “Smoke” is FUEL! Firefighters use the term “smoke” when addressing the solids, aerosols, and gases being produced by the hostile fire. Soot, dust, and fibers make up the solids. Aerosols are suspended liquids such as water, trace acids, and hydrocarbons (oil). Gases are numerous in smoke – mass quantities of Carbon Monoxide lead the list. Concept #2: The Fuels have changed: The contents and structural elements being burned are of LOWER MASS than previous decades. These materials are also more synthetic than ever. Concept #3: The Fuels have triggers There are “Triggers” for Hostile Fire Events. Flash point triggers a smoke explosion. Fire Point triggers rapid fire spread, ignition temperature triggers auto ignition, Backdraft, and Flashover. Hostile fire events (know the warning signs): Flashover: The classic American Version of a Flashover is the simultaneous ignition of fuels within a compartment due to reflective radiant heat – the “box” is heat saturated and can’t absorb any more. The British use the term Flashover to describe any ignition of the smoke cloud within a structure. Signs: Turbulent smoke, rollover, and auto-ignition outside the box. Backdraft: A “true” backdraft occurs when oxygen is introduced into an O2 deficient environment that is charged with gases (pressurized) at or above their ignition temperature. -

Respirator Usage by Wildland Firefighters

United States Department of Agriculture Fire Forest Service Management National Technology & Development Program March 2007 Tech Tips 5200 0751 1301—SDTDC Respirator Usage by Wildland Firefighters David V. Haston, P.E., Mechanical Engineer Tech Tip Highlights ß Based on a 7-year comprehensive study by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG), a 1997 consensus conference concluded that routine use of air purifying respirators (APRs) should not be required. ß APRs provide protection against some, but not all harmful components of wood smoke, and may expose firefighters to higher levels of unfiltered contaminants, such as carbon monoxide. In addition, APRs do not protect firefighters against superheated gases and do not supply oxygen. ß Firefighters may use APRs on a voluntary basis if certain conditions are met. Introduction All firefighters, fire management officers, and safety personnel should understand the issues related to using air purifying respirators (APRs) in the wildland firefighting environment. This Tech Tip is intended to provide information regarding the regulatory requirements for using APRs, how APRs function, and the benefits and risks associated with their use. Respirator Types and Approvals Respirators are tested and approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) in accordance with 42 CFR Part 84 (Approval of Respiratory Protection Devices). Respirators fall into two broad classifications: APRs that filter ambient air, and atmosphere-supplying respirators that supply clean air from another source, such as self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). APRs include dust masks, mouthpiece respirators (used for escape only), half- and full-facepiece respirators, gas masks, and powered APRs. They use filters or cartridges that remove harmful contaminants when air is passed through the air-purifying element. -

NFIRS 5.0 Self-Study Program Introduction and Overview

U.S. Fire Administration NFIRS 5.0 Self-Study Program National Fire Incident Reporting System October 2006 National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS) 5.0 Self-Study Program Department of Homeland Security United States Fire Administration National Fire Data Center Contents – NFIRS 5.0 Self-Study Program INTRODUCTION & OVERVIEW ............................................ Intro-1 BASIC MODULE: NFIRS-1 ......................................................1-1 SUPPLEMENTAL FORM: NFIRS-1S ..............................................1S-1 FIRE MODULE: NFIRS-2 .......................................................2-1 STRUCTURE FIRE MODULE: NFIRS-3 ........................................... .3-1 CIVILIAN FIRE CASUALTY MODULE: NFIRS-4 ......................................4-1 FIRE SERVICE CASUALTY MODULE: NFIRS-5 .......................................5-1 EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES (EMS) MODULE: NFIRS-6 .......................... .6-1 HAZARDOUS MATERIALS MODULE: NFIRS-7 ..................................... .7-1 WILDLAND FIRE MODULE: NFIRS-8 ............................................ .8-1 APPARATUS OR RESOURCES MODULE: NFIRS-9 ....................................9-1 PERSONNEL MODULE: NFIRS-10 ...............................................10-1 ARSON & JUVENILE FIRESETTER MODULE: NFIRS-11 ...............................11-1 SUMMARY AND WRAP UP ....................................................12-1 APPENDIX A: SCENARIO ANSWERS ..................................... APPENDIX A-1 APPENDIX B: PRETEST ANSWERS .......................................APPENDIX -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families

A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families JULY 2019 A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families July 2019 NOTE: This publication is a draft proof of concept for NWCG member agencies. The information contained is currently under review. All source sites and documents should be considered the authority on the information referenced; consult with the identified sources or with your agency human resources office for more information. Please provide input to the development of this publication through your agency program manager assigned to the NWCG Risk Management Committee (RMC). View the complete roster at https://www.nwcg.gov/committees/risk-management-committee/roster. A Preparedness Guide for Firefighters and Their Families provides honest information, resources, and conversation starters to give you, the firefighter, tools that will be helpful in preparing yourself and your family for realities of a career in wildland firefighting. This guide does not set any standards or mandates; rather, it is intended to provide you with helpful information to bridge the gap between “all is well” and managing the unexpected. This Guide will help firefighters and their families prepare for and respond to a realm of planned and unplanned situations in the world of wildland firefighting. The content, designed to help make informed decisions throughout a firefighting career, will cover: • hazards and risks associated with wildland firefighting; • discussing your wildland firefighter job with family and friends; • resources for peer support, individual counsel, planning, and response to death and serious injury; and • organizations that support wildland firefighters and their families. Preparing yourself and your family for this exciting and, at times, dangerous work can be both challenging and rewarding. -

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

To Provide Procedures and Guidelines for Personnel Responding to and Operating at Working Structure Fire Incidents

I. INTRODUCTION A. Purpose: To provide procedures and guidelines for personnel responding to and operating at working structure fire incidents. B. Scope: This instruction applies to all personnel responsible for performing tasks in the operational area of a structure fire. C. Author: The chief deputy of Emergency Operations is responsible for the content, revision, and annual review of this instruction. D. Definitions: See Appendix I E. Underwriters Lab (UL) studies: See Appendix II F. Operational Modes: See Appendix III II. RESPONSIBILITY A. The first arriving company officer is responsible for: 1. Performing an initial size-up. 2. Developing a mental incident action plan (IAP) to determine the initial operational mode. 3. Transmitting the size-up radio report to the Los Angeles Communications Center (LACC). 4. Taking initial actions consistent with the incident priorities and tactical operations of the incident. 5. Considering the use of transitional attack when operating in the offensive mode and with fire showing. 6. Establishing the Incident Command System (ICS). 08/13/2014 1 of 23 V11-C3-S2 Structure Fires Structure Firefighting Standard Operating Procedures B. The incident commander (IC) is responsible for: 1. Overall management of the incident. 2. Identifying incident objectives. 3. Communicating the current operational mode and providing status reports to LACC. C. The incident safety officer is responsible for: 1. Identifying and evaluating hazards, knowing the current operational mode, and advising the IC in the area of personnel safety. The safety officer has the authority to alter, suspend, or terminate any unsafe activity. The safety officer investigates accidents and near misses involving Department personnel. -

2019 Interagency Standards for Fire and Fire Aviation Operations

Executive Summary of Changes - Interagency Standards for Fire and Fire Aviation Operations 2019 Chapter 1 – Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy and Doctrine Overview • Changed chapter title from “Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy Overview” to “Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy and Doctrine Overview.” • Clarified text under subheading “Guiding Principles of the Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy,” 7., regarding FMPs and activities incorporate firefighter exposure, public health, compliance with Clean Air Act and environment quality considerations. • Under heading “Definitions”: o Clarified “Wildland Fire” as a general term describing any non-structure fire that occurs in the wildland. o Clarified “Suppression” as all the work of extinguishing a fire or confining fire spread. o Clarified “Protection” as the actions taken to mitigate the adverse effects of fire on environmental, social, political, and economical effects of fire. o Clarified “Prescribed Fire” as a wildland fire originating from a planned ignition to meet specific objectives identified in a written, approved, prescribed fire plan for which NEPA requirements (where applicable) have been met prior to ignition. o Inserted “National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS),” “Criteria Pollutants,” “State Implementation Plan (SIP),” “Federal Implementation Plan (FIP),” “Attainment Area,” “Nonattainment Area,” “Maintenance Area,” and associated text. Chapter 2 – BLM • Clarified under heading “Fire and Aviation Directorate” that the BLM Fire and Aviation Directorate -

NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management PMS 902 April 2021 NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management April 2021 PMS 902 The NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management, assists participating agencies of the NWCG to constructively work together to provide effective execution of each agency’s incident business management program by establishing procedures for: • Uniform application of regulations on the use of human resources, including classification, payroll, commissary, injury compensation, and travel. • Acquisition of necessary equipment and supplies from appropriate sources in accordance with applicable procurement regulations. • Management and tracking of government property. • Financial coordination with the jurisdictional agency and maintenance of finance, property, procurement, and personnel records, and forms. • Use and coordination of incident business management functions as they relate to sharing of resources among federal, state, and local agencies, including the military. • Documentation and reporting of claims. • Documentation of costs and cost management practices. • Administrative processes for all-hazards incidents. Uniform application of interagency incident business management standards is critical to successful interagency fire operations. These standards must be kept current and made available to incident and agency personnel. Changes to these standards may be proposed by any agency for a variety of reasons: new law or regulation, legal interpretation or opinion, clarification of meaning, etc. If the proposed change is relevant to the other agencies, the proponent agency should first obtain national headquarters’ review and concurrence before forwarding to the NWCG Incident Business Committee (IBC). IBC will prepare draft NWCG amendments for all agencies to review before finalizing and distributing. -

Structural Fire Assignment

Cumberland County Standard Operating Guideline Order of Apparatus Arrival - Structural Fire Assignment Purpose: To establish a standard method for fire apparatus arrival and positioning at structure fire incidents. All personnel must use the procedures below during structure firefighting operations. It is important to note that unless otherwise directed by the Incident Commander you must follow this apparatus positioning guideline. Unit Officers must LIMIT radio transmissions to critical fire ground information. Single units should routinely not contact the Incident Commander for “instructions and assignments”. Procedure: While enroute to the incident scene Unit Officers must maintain situational awareness of their specific location and order of apparatus arrival. Personnel must not take action until their Unit Officer in charge directs them to do so. All drivers who are not specifically assigned to apparatus operations will assemble with their crew. Fire ground discipline is critical during all incident responses. In addition to the listed responsibilities Unit Officers must: A. Maintain crew integrity B. Ensure that personnel and apparatus take their assigned positions C. Follow this and other applicable policies, including the Incident Command System. The IC may modify these assignments as necessary. First Due Engine 1. Unit Responsibilities Initiate water supply by laying a supply line from the most suitable water supply, beginning a split lay or give instructions for reverse lay as necessary. Position the engine on Side Alpha, reserving adequate space for the aerial unit to position. Connect to the building standpipe and/or sprinkler system, if so equipped, on or closest to Side Alpha. Activate VTAC for optimal portable radio coverage. -

Structure Fires in Dormitories, Fraternities, Sororities and Barracks

STRUCTURE FIRES IN DORMITORIES, FRATERNITIES, SORORITIES AND BARRACKS Jennifer D. Flynn August 2009 National Fire Protection Association Fire Analysis and Research Division STRUCTURE FIRES IN DORMITORIES, FRATERNITIES, SORORITIES AND BARRACKS Jennifer D. Flynn August 2009 National Fire Protection Association Fire Analysis and Research Division Abstract In 2003-2006, U.S. fire departments responded to an estimated annual average of 3,570 structure fires in dormitories, fraternities, sororities, and barracks. These fires caused an annual average of 7 civilian deaths, 54 civilian fire injuries, and $29.4 million in direct property damage. Fires in these properties accounted for 0.7% of all reported structure fires within the same time period. These estimates are based on data from the U.S. Fire Administration’s (USFA) National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS) and the National Fire Protection Association’s (NFPA) annual fire department experience survey. Cooking equipment was involved in 75% of reported structure fires. Only 5% of fires in these properties began in the bedroom, but these fires accounted for 62% of the civilian deaths and 26% of civilian fire injuries. Fires in dormitories, fraternities, sororities, and barracks are more common during the evening hours, between 5 p.m. and 11 p.m., and on weekends. Keywords: fire statistics, dormitory fires, fraternity fires, sorority fires, barrack fires Acknowledgements The National Fire Protection Association thanks all the fire departments and state fire authorities who participate in the National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS) and the annual NFPA fire experience survey. These firefighters are the original sources of the detailed data that make this analysis possible. -

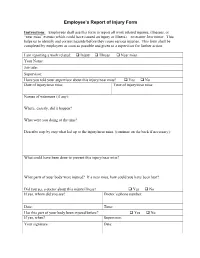

Employee's Report of Injury Form

Employee’s Report of Injury Form Instructions: Employees shall use this form to report all work related injuries, illnesses, or “near miss” events (which could have caused an injury or illness) – no matter how minor. This helps us to identify and correct hazards before they cause serious injuries. This form shall be completed by employees as soon as possible and given to a supervisor for further action. I am reporting a work related: Injury Illness Near miss Your Name: Job title: Supervisor: Have you told your supervisor about this injury/near miss? Yes No Date of injury/near miss: Time of injury/near miss: Names of witnesses (if any): Where, exactly, did it happen? What were you doing at the time? Describe step by step what led up to the injury/near miss. (continue on the back if necessary): What could have been done to prevent this injury/near miss? What parts of your body were injured? If a near miss, how could you have been hurt? Did you see a doctor about this injury/illness? Yes No If yes, whom did you see? Doctor’s phone number: Date: Time: Has this part of your body been injured before? Yes No If yes, when? Supervisor: Your signature: Date: Supervisor’s Accident Investigation Form Name of Injured Person _________________________________________________ Date of Birth _________________ Telephone Number ____________________ Address ______________________________________________________________ City _____________________________ State_______ Zip _____________ (Circle one) Male Female What part of the body was injured? Describe