Encrusted Urinary Stents: Evaluation and Endourologic Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urology Services in the ASC

Urology Services in the ASC Brad D. Lerner, MD, FACS, CASC Medical Director Summit ASC President of Chesapeake Urology Associates Chief of Urology Union Memorial Hospital Urologic Consultant NFL Baltimore Ravens Learning Objectives: Describe the numerous basic and advanced urology cases/lines of service that can be provided in an ASC setting Discuss various opportunities regarding clinical, operational and financial aspects of urology lines of service in an ASC setting Why Offer Urology Services in Your ASC? Majority of urologic surgical services are already outpatient Many urologic procedures are high volume, short duration and low cost Increasing emphasis on movement of site of service for surgical cases from hospitals and insurance carriers to ASCs There are still some case types where patients are traditionally admitted or placed in extended recovery status that can be converted to strictly outpatient status and would be suitable for an ASC Potential core of fee-for-service case types (microsurgery, aesthetics, prosthetics, etc.) Increasing Population of Those Aged 65 and Over As of 2018, it was estimated that there were 51 million persons aged 65 and over (15.63% of total population) By 2030, it is expected that there will be 72.1 million persons aged 65 and over National ASC Statistics - 2017 Urology cases represented 6% of total case mix for ASCs Urology cases were 4th in median net revenue per case (approximately $2,400) – behind Orthopedics, ENT and Podiatry Urology comprised 3% of single specialty ASCs (5th behind -

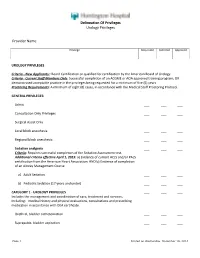

Delineation of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name

Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name: Privilege Requested Deferred Approved UROLOGY PRIVILEGES Criteria - New Applicants:: Board Certification or qualified for certification by the American Board of Urology. Criteria - Current Staff Members Only: Successful completion of an ACGME or AOA approved training program; OR demonstrated acceptable practice in the privileges being requested for a minimum of five (5) years. Proctoring Requirements: A minimum of eight (8) cases, in accordance with the Medical Staff Proctoring Protocol. GENERAL PRIVILEGES: Admit ___ ___ ___ Consultation Only Privileges ___ ___ ___ Surgical Assist Only ___ ___ ___ Local block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Regional block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Sedation analgesia ___ ___ ___ Criteria: Requires successful completion of the Sedation Assessment test. Additional criteria effective April 1, 2015: a) Evidence of current ACLS and/or PALS certification from the American Heart Association; AND b) Evidence of completion of an Airway Management Course a) Adult Sedation ___ ___ ___ b) Pediatric Sedation (17 years and under) ___ ___ ___ CATEGORY 1 - UROLOGY PRIVILEGES ___ ___ ___ Includes the management and coordination of care, treatment and services, including: medical history and physical evaluations, consultations and prescribing medication in accordance with DEA certificate. Urethral, bladder catheterization ___ ___ ___ Suprapubic, bladder aspiration ___ ___ ___ Page 1 Printed on Wednesday, December 10, 2014 Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider -

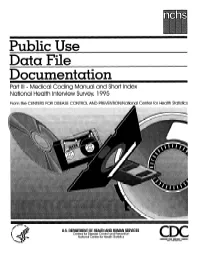

Public Use Data File Documentation

Public Use Data File Documentation Part III - Medical Coding Manual and Short Index National Health Interview Survey, 1995 From the CENTERSFOR DISEASECONTROL AND PREVENTION/NationalCenter for Health Statistics U.S. DEPARTMENTOF HEALTHAND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics CDCCENTERS FOR DlSEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTlON Public Use Data File Documentation Part Ill - Medical Coding Manual and Short Index National Health Interview Survey, 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTHAND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsville, Maryland October 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SECTION I. INTRODUCTION AND ORIENTATION GUIDES A. Brief Description of the Health Interview Survey ............. .............. 1 B. Importance of the Medical Coding ...................... .............. 1 C. Codes Used (described briefly) ......................... .............. 2 D. Appendix III ...................................... .............. 2 E, The Short Index .................................... .............. 2 F. Abbreviations and References ......................... .............. 3 G. Training Preliminary to Coding ......................... .............. 4 SECTION II. CLASSES OF CHRONIC AND ACUTE CONDITIONS A. General Rules ................................................... 6 B. When to Assign “1” (Chronic) ........................................ 6 C. Selected Conditions Coded ” 1” Regardless of Onset ......................... 7 D. When to Assign -

Ureteroscopic Treatment of Larger Renal Calculi (>2 Cm)

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons Department of Urology Faculty Papers Department of Urology 9-1-2012 Ureteroscopic treatment of larger renal calculi (>2 cm). Demetrius H. Bagley Thomas Jefferson University Kelly A. Healy Thomas Jefferson University Nir Kleinmann Thomas Jefferson University Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/urologyfp Part of the Urology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Bagley, Demetrius H.; Healy, Kelly A.; and Kleinmann, Nir, "Ureteroscopic treatment of larger renal calculi (>2 cm)." (2012). Department of Urology Faculty Papers. Paper 45. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/urologyfp/45 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Urology Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. Arab Journal of Urology (2012) 10, 296–300 Arab Journal of Urology (Official Journal of the Arab -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Urolithiasis

Guidelines on Urolithiasis C. Türk (chairman), T. Knoll (vice-chairman), A. Petrik, K. Sarica, M. Straub, C. Seitz © European Association of Urology 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. METHODOLOGY 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Data identification 7 1.3 Evidence sources 7 1.4 Level of evidence and grade of recommendation 7 1.5 Publication history 8 1.5.1 Summary of changes 8 1.6 References 9 2. CLASSIFICATION OF STONES 10 2.1 Stone size 10 2.2 Stone location 10 2.3 X-ray characteristics 10 2.4 Aetiology of stone formation 10 2.5 Stone composition 10 2.6 Risk groups for stone formation 11 2.7 References 12 3. DIAGNOSIS 12 3.1 Diagnostic imaging 12 3.1.1 Evaluation of patients with acute flank pain 13 3.1.2 Evaluation of patients for whom further treatment of renal stones is planned 14 3.1.3 References 14 3.2 Diagnostics - metabolism-related 15 3.2.1 Basic analysis - non-emergency stone patients 16 3.2.2 Analysis of stone composition 16 3.3 References 17 4. TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH RENAL COLIC 17 4.1 Renal colic 17 4.1.1 Pain relief 17 4.1.2 Prevention of recurrent renal colic 18 4.1.3 Recommendations for analgesia during renal colic 18 4.1.4 References 18 4.2 Management of sepsis in obstructed kidney 19 4.2.1 Decompression 19 4.2.2 Further measures 20 4.2.3 References 20 5. STONE RELIEF 21 5.1 Observation of ureteral stones 21 5.1.1 Stone-passage rates 21 5.2 Observation of kidney stones 21 5.3 Medical expulsive therapy (MET) 21 5.3.1 Choice of medical agent 22 5.3.1.1 Alpha-blockers 22 5.3.1.2 Calcium-channel blockers 22 5.3.1.2.1 Tamsulosin versus -

Surgical Management of Urolithiasis in Patients After Urinary Diversion

Surgical Management of Urolithiasis in Patients after Urinary Diversion Wen Zhong1, Bicheng Yang1, Fang He2, Liang Wang3, Sunil Swami4, Guohua Zeng1* 1 Department of Urology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangdong Key Laboratory of Urology, Guangzhou, China, 2 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China, 3 Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, College of Public Health, East Tennessee State University, Johnson, Tennessee, United States of America, 4 Department of Epidemiology, College of Public Health and Health Professions, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, United States of America Abstract Objective: To present our experience in surgical management of urolithiasis in patients after urinary diversion. Patients and Methods: Twenty patients with urolithiasis after urinary diversion received intervention. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy, percutaneous based antegrade ureteroscopy with semi-rigid or flexible ureteroscope, transurethral reservoir lithotripsy, percutaneous pouch lithotripsy and open operation were performed in 8, 3, 2, 6, and 1 patients, respectively. The operative finding and complications were retrospectively collected and analyzed. Results: The mean stone size was 4.563.1 (range 1.5–11.2) cm. The mean operation time was 82.0611.5 (range 55–120) min. Eighteen patients were rendered stone free with a clearance of 90%. Complications occurred in 3 patients (15%). Two patients (10%) had postoperative fever greater than 38.5uC, and one patient (5%) suffered urine extravasations from percutaneous tract. Conclusions: The percutaneous based procedures, including percutaneous nephrolithotomy, antegrade ureteroscopy with semi-rigid ureteroscope or flexible ureteroscope from percutaneous tract, and percutaneous pouch lithotripsy, provides a direct and safe access to the target stones in patients after urinary diversion, and with high stone free rate and minor complications. -

Simplified Operative Nephroscopy

SIMPLIFIED OPERATIVE NEPHROSCOPY STEPHEN A. KOFF, M.D. From the Department of Surgery, Section of Urology, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan ABSTRACT - Zntraoperative nephroscopy is a valuable and practical adjunct to renal surgery. A simpli$ed methodology is described usingfamiliar cystoscopic equipment and techniques. Its particular usefulness in the definition of small radiolucent defects of the renal collecting system is illustrated. Intraoperative nephroscopy is a technique for en- The instrument ordinarily used is a 24 F doscopic visualization of the renal pelvis and McCarthy panendoscope with a straight sheath calyceal system. When operation is indicated, it fitted with water and lighting conduits in a fashion can be a valuable means of assisting in the diag- identical to that used during cystoscopy. Biopsy nosis and treatment of calculi and lesions in the forceps and fulgurating electrodes are available as renal collecting system. As originally described needed. by Trattner,’ standard endoscopic equipment and At operation the kidney is exposed and maneuvers were used to perform the intrarenal mobilized completely. The instrument is care- inspection and manipulations. Modifications of fully inserted through a small pyelotomy incision this equipment and technique have generated a on either the anterior or posterior surface of the more elaborate procedure and may have reduced pelvis. No attempt is made to prevent leakage of its practicability for routine use.2-4 irrigating fluid, but the wound is carefully packed We have found intraoperative nephroscopy to with pads, and the fluid is suctioned off as soon as be a valuable and practical adjunct to open renal it appears. -

1 Supplementary Material Urolithiasis Read Codes

Supplementary Material Urolithiasis Read Codes Read code Description Counta K120.12 Renal calculus 22804 K120.13 Renal stone 7508 7B0B.00 Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy for renal calculus 6354 K120.00 Calculus of kidney 5289 K121.11 Ureteric calculus 4691 7B07.12 Percutaneous lithotripsy of renal calculus 4508 4G4..11 O/E: kidney stone 4467 K121.12 Ureteric stone 4188 C341111 Renal stone - uric acid 4142 K12z.00 Urinary calculus NOS 3863 K12..00 Calculus of kidney and ureter 3355 K121.00 Calculus of ureter 3045 K120z00 Renal calculus NOS 2339 4G4..00 O/E: renal calculus 1989 7B18.00 Ureteroscopic operations for ureteric calculus 1736 7B1C.00 Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy of ureteric calculus 1638 7B07.13 PCNL - Percutaneous nephrolithotomy 1163 4G6..00 O/E - ureteric calculus 1142 7B07.00 Percutaneous renal stone surgery 957 7B15000 Unspecified open ureterolithotomy 954 7B05600 Pyelolithotomy 953 7B05800 Simple nephrolithotomy 785 K120.11 Nephrolithiasis NOS 685 K12..12 Urinary calculus 514 7B05000 Unspecified open removal of calculus from kidney 467 7B18100 Other ureteroscopic fragmentation of ureteric calculus 461 7B18200 Ureteroscopic extraction of ureteric calculus 426 7B19.00 Cystoscopic removal of ureteric calculus 336 7B19000 Cystoscopic laser lithotripsy of ureteric calculus 309 7B18000 Ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy of ureteric calculus 306 7B17111 Other nephroscopic lithotripsy of ureteric calculus 290 K12..11 Kidney calculus 272 7B0C200 Percutaneous nephrolithotomy NEC 183 7B0B000 ESWL for renal calculus of unspecified -

Effects of Various Catheter Fix Sites on Catheter‑Associated Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 21: 47, 2021 Effects of various catheter fix sites on catheter‑associated lower urinary tract symptoms LIKUN ZHU1,2, RUI JIANG1,2, XIANGJUN KONG1,2, XINWEI WANG1,2, LIJUN PEI1,2, QINGFU DENG1,2 and XU LI1,2 1Department of Urology Surgery, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, 2Sichuan Clinical Medical Research Center for Nephropathy, Luzhou, Sichuan 646000, P.R. China Received March 5, 2020; Accepted July 17, 2020 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2020.9478 Abstract. The present study aimed to compare the effects of urethral (Foley) catheters are used annually in the United various catheter fix sites on catheter‑associated lower urinary States (1) and ~20% of hospitalized patients have a urethral tract symptoms (CALUTS) in 450 patients who underwent catheter at any given time (2,3). Catheter‑associated lower surgical removal of upper urinary calculi 24 h earlier. All patients urinary tract symptoms (CALUTS) refer to a range of had 16 French Foley catheters inserted and the balloons were symptoms, including frequency, urgency, burning during filled. In group A, the catheters were fixed on the top one‑third of micturition, odynuria and suprapubic pain (3). These symp‑ the thigh. In group B, the catheters were fixed on the abdominal toms may be caused by involuntary detrusor contractions wall. Patients in whom the catheters were neither fixed on the induced by activation of muscarinic type III receptors, also thigh nor abdominal wall were designated as controls. There known as M3mAChR, and the increased release of acetylcho‑ were 150 patients in each group. CALUTS, such as frequency, line, which are caused by reactions of the mucosa in the trigone urgency, burning during micturition, odynuria, bladder pain and and urethra after insertion of a catheter (1‑8). -

Laparoscopic - Assisted Transpyelic Rigid Nephroscopy - Simple Alternative When Flexible Ureteroscopy Is Not Available ______

VIDEO SECTION Vol. 42 (4): 853-854, July - August, 2016 doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2014.0588 Laparoscopic - assisted transpyelic rigid nephroscopy - simple alternative when flexible ureteroscopy is not available _______________________________________________ Marcos Tobias-Machado 1, Alexandre Kiyoshi Hidaka 1, Igor Nunes-Silva 1, Carlos Alberto Chagas 2, Leandro Correa Leal 2, Antonio Carlos Lima Pompeo 1 1 Departamento de Urologia, Faculdade de Medicina do ABC - FMABC - Santo André, São Paulo, Brasil; 2 Departamento de Urologia do Meridional Hospital - Cariacica, Espírito Santo, Brasil _______________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Introduction: In special situations such as malrotated or ectopic kidneys and UPJ stenosis treatment of renal lithiasis can be challenging. In these rare cases laparoscopy can be indicated. Objective: Describe the Laparoscopic-assisted rigid nephroscopy performed via transpyelic approach and report the feasibility. Patients and methods: We present two cases of caliceal lithiasis. The first is a patient that ESWL and previous percutaneous lithotripsy have failed, with pelvic kidney where laparoscopic dissection of renal pelvis was carried out followed by nephroscopy utilizing the 30 Fr rigid nephroscope to remove the cal- culus. Ideal angle between the major axis of renal pelvis and the rigid nephroscope to allow success with this technique was 60-90 grades. In the second case, the kidney had a dilated infundibulum. Results: The operative time was 180 minutes for both procedures. No significant blood loss or periope- rative complications occurred. The bladder catheter was removed in the postoperative day 1 and Penrose drain on day 2 when patients were discharged. The convalescence was completed after 3 weeks. Patients were stone free without symptons in one year of follow-up. -

Coding Companion for Urology/Nephrology a Comprehensive Illustrated Guide to Coding and Reimbursement

Coding Companion for Urology/Nephrology A comprehensive illustrated guide to coding and reimbursement 2015 Contents Getting Started with Coding Companion .............................i Scrotum ..........................................................................328 Integumentary.....................................................................1 Vas Deferens....................................................................333 Arteries and Veins ..............................................................15 Spermatic Cord ...............................................................338 Lymph Nodes ....................................................................30 Seminal Vesicles...............................................................342 Abdomen ..........................................................................37 Prostate ...........................................................................345 Kidney ...............................................................................59 Reproductive ...................................................................359 Ureter ..............................................................................116 Intersex Surgery ..............................................................360 Bladder............................................................................153 Vagina .............................................................................361 Urethra ............................................................................226 Medicine