The Human Rights Situation in Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

Canada, the Us and Cuba

CANADA, THE US AND CUBA CANADA, THE US AND CUBA HELMS-BURTON AND ITS AFTERMATH Edited by Heather N. Nicol Centre for International Relations, Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada 1999 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Canada, the US and Cuba : Helms-Burton and its aftermath (Martello papers, ISSN 1183-3661 ; 21) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-88911-884-1 1. United States. Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act of 1996. 2. Canada – Foreign relations – Cuba. 3. Cuba – Foreign relations – Canada. 4. Canada – Foreign relations – United States. 5. United States – Foreign relations – Canada. 6. United States – Foreign relations – Cuba. 7. Cuba – Foreign relations – United States. I. Nicol, Heather N. (Heather Nora), 1953- . II. Queen’s University (Kingston, Ont.). Centre for International Relations. III. Series. FC602.C335 1999 327.71 C99-932101-3 F1034.2.C318 1999 © Copyright 1999 The Martello Papers The Queen’s University Centre for International Relations (QCIR) is pleased to present the twenty-first in its series of security studies, the Martello Papers. Taking their name from the distinctive towers built during the nineteenth century to de- fend Kingston, Ontario, these papers cover a wide range of topics and issues rele- vant to contemporary international strategic relations. This volume presents a collection of insightful essays on the often uneasy but always interesting United States-Cuba-Canada triangle. Seemingly a relic of the Cold War, it is a topic that, as editor Heather Nicol observes, “is always with us,” and indeed is likely to be of greater concern as the post-Cold War era enters its second decade. -

Trading with the Enemy: Opening the Door to U.S. Investment in Cuba

ARTICLES TRADING WITH THE ENEMY: OPENING THE DOOR TO U.S. INVESTMENT IN CUBA KEVIN J. FANDL* ABSTRACT U.S. economic sanctions on Cuba have been in place for nearly seven deca- des. The stated intent of those sanctionsÐto restore democracy and freedom to CubaÐis still used as a justi®cation for maintaining harsh restrictions, despite the fact that the Castro regime remains in power with widespread Cuban public support. Starving the Cuban people of economic opportunities under the shadow of sanctions has signi®cantly limited entrepreneurship and economic development on the island, despite a highly educated and motivated popula- tion. The would-be political reformers and leaders on the island emigrate, thanks to generous U.S. immigration policies toward Cubans, leaving behind the Castro regime and its ardent supporters. Real change on the island will come only if the United States allows Cuba to restart its economic engine and reengage with global markets. Though not a guarantee of political reform, eco- nomic development is correlated with demand for political change, giving the economic development approach more potential than failed economic sanctions. In this short paper, I argue that Cuba has survived in spite of the U.S. eco- nomic embargo and that dismantling the embargo in favor of open trade poli- cies would improve the likelihood of Cuba becoming a market-friendly communist country like China. I present the avenues available today for trade with Cuba under the shadow of the economic embargo, and I argue that real po- litical change will require a leap of faith by the United States through removal of the embargo and support for Cuba's economic development. -

Constitution of Cuba

Constitution of Cuba Preamble WE, CUBAN CITIZENS, heirs and continuators of the creative work and the traditions of combativity, firmness, heroism and sacrifice fostered by our ancestors; by the Indians who preferred extermination to submission; by the slaves who rebelled against their masters; by those who awoke the national consciousness and the ardent Cuban desire for an independent homeland and liberty; by the patriots who in 1868 launched the wars of independence against Spanish colonialism and those who in the last drive of 1895 brought them to the victory of 1898, victory usurped by the military intervention and occupation of Yankee imperialism; by the workers, peasants, students, and intellectuals who struggled for over fifty years against imperialist domination, political corruption, the absence of people’s rights and liberties, unemployment and exploitation by capitalists and landowners; by those who promoted, joined and developed the first organization of workers and peasants, spread socialist ideas and founded the first Marxist and Marxist-Leninist movements; by the members of the vanguard of the generation of the centenary of the birth of Martí who, imbued with his teachings, led us to the people’s revolutionary victory of January; by those who defended the Revolution at the cost of their lives, thus contributing to its definitive consolidation; by those who, en masse, accomplished heroic internationalist missions; GUIDED by the ideology of José Martí, and the sociopolitical ideas of Marx, Engels, and Lenin; SUPPORTED by -

New Castro Same Cuba

New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-562-8 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2009 1-56432-562-8 New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era I. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 7 II. Illustrative Cases ......................................................................................................................... 11 Ramón Velásquez -

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

Introduction Chapter 1 Chapter 2

Notes Introduction 1. I am grateful to Richard Boyd for his teaching and supervision, as a result of which I was introduced to the eminent importance, both within and outside philosophy, of arguments for naturalistic realism in Anglo- American analytic philosophy. See Boyd 1982, 1983, 1985, 1988, 1999, 2010. 2. This is how the term is spelled in Goodman 1973. Chapter 1 1. This took place at a talk at the University of Havana on the occasion of receiving an honorary degree December 8, 2001, Havana, Cuba. 2. Take, for example, Senel Paz saying, “I have always thought that it is the duty of the intellectuals . to examine closely all of our errors and negative tendencies, to study them with courage and without shame” (my translation) in Heras 1999: 148. 3. I have discussed this view at some length in Babbitt 1996. 4. Julia Sweig’s statement is significant given that she was director of Latin Ameri- can studies at the Council of Foreign Relations, a major foreign policy forum for the US government. See Sweig 2007, cited in Veltmeyer & Rushton 2013: 301. 5. “US Governor in First Trip to Castro’s Cuba” (1999, October 24), New York Times, p. 14, http:// search .proquest .com .proxy .queensu .ca /docview /110125370 / pageviewPDF ?accountid = 6180 [accessed March 10, 2013]. 6. The fact- value distinction emerged in European Enlightenment philosophy, originating, arguably, with Hume (1711– 1776) who argued that normative arguments (about value) cannot be derived logically from arguments about what exists. 7. The view that the mind, understood as consciousness, is physical, although distinctly so, is defended by philosophers of mind (Searle 1998; see also Prado 2006). -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago De Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago de Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof, Co-Chair Professor Rebecca J. Scott, Co-Chair Associate Professor Paulina L. Alberto Professor Emerita Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Jean M. Hébrard, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Professor Martha Jones To Paul ii Acknowledgments One of the great joys and privileges of being a historian is that researching and writing take us through many worlds, past and present, to which we become bound—ethically, intellectually, emotionally. Unfortunately, the acknowledgments section can be just a modest snippet of yearlong experiences and life-long commitments. Archivists and historians in Cuba and Spain offered extremely generous support at a time of severe economic challenges. In Havana, at the National Archive, I was privileged to get to meet and learn from Julio Vargas, Niurbis Ferrer, Jorge Macle, Silvio Facenda, Lindia Vera, and Berta Yaque. In Santiago, my research would not have been possible without the kindness, work, and enthusiasm of Maty Almaguer, Ana Maria Limonta, Yanet Pera Numa, María Antonia Reinoso, and Alfredo Sánchez. The directors of the two Cuban archives, Martha Ferriol, Milagros Villalón, and Zelma Corona, always welcomed me warmly and allowed me to begin my research promptly. My work on Cuba could have never started without my doctoral committee’s support. Rebecca Scott’s tireless commitment to graduate education nourished me every step of the way even when my self-doubts felt crippling. -

Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009

16 April 2009 OpenȱSourceȱCenter Report Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009 Raul Castro has overhauled the leadership of top government bodies, especially those dealing with the economy, since he formally succeeded his brother Fidel as president of the Councils of State and Ministers on 24 February 2008. Since then, almost all of the Council of Ministers vice presidents have been replaced, and more than half of all current ministers have been appointed. The changes have been relatively low-key, but the recent ousting of two prominent figures generated a rare public acknowledgement of official misconduct. Fidel Castro retains the position of Communist Party first secretary, and the party leadership has undergone less turnover. This may change, however, as the Sixth Party Congress is scheduled to be held at the end of this year. Cuba's top military leadership also has experienced significant turnover since Raul -- the former defense minister -- became president. Names and photos of key officials are provided in the graphic below; the accompanying text gives details of the changes since February 2008 and current listings of government and party officeholders. To view an enlarged, printable version of the chart, double-click on the following icon (.pdf): This OSC product is based exclusively on the content and behavior of selected media and has not been coordinated with other US Government components. This report is based on OSC's review of official Cuban websites, including those of the Cuban Government (www.cubagob.cu), the Communist Party (www.pcc.cu), the National Assembly (www.asanac.gov.cu), and the Constitution (www.cuba.cu/gobierno/cuba.htm). -

Educational Experiences During the “Special Period” in Cuba

Dr. Martin Camacho Dean, Fain Collegeof Fine Arts Midwestern State University Arts Education in Cuba Revolutionary Period Expansion of artistic education and prioritization from 1961 Incorporation of music, dance and visual arts disciplines in primary education (1975) Creation of the Escuela Nacional de Arte System ENA (National Schools of Arts) 1962 – Music, Visual Arts, Theatre, Ballet, Dance, Circus Creation of Specialized Artistic Elementary System (Vocational Schools) ISA – Instituto Superior de Arte University of the Arts Created in 1976 for three disciplines: music, visual arts, and theatre. It recently added Media Arts (FAMCA) and four units outside Havana Specialized Artistic Education Music Example VOCATIONAL SHOOLS - Music Children enter Vocational Music Schools between ages 6-10 and complete K 1-9. Schools are available at the province (state) level. NATIONAL SCHOOLS OF ART - After a competitive process, selected students move to the National Schools or Art to complete professional training and grades K 10-12. Schools are available only at the regional level. UNIVERSITY - After a competitive process, selected students are admitted at ISA, University of the Arts, the only institution of higher education in the arts in Cuba. Cuban Curricula and Soviet Support (Music) Musical educational model was copied and supported by and large by the Soviet Union. The music curricula favored the formation of trained musicians in classical and the Western European tradition. Disciplines such as jazz, afro-Cuban, or traditional Cuban music were not particularly thought as strong within the music curricula, but as a co-curricular or extra-curricular activity. Special Period – Periodo Especial of 1990 The collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and the toughening of the American Embargo (Torricelli and Helms-Burton law) brought very negative economic consequences. -

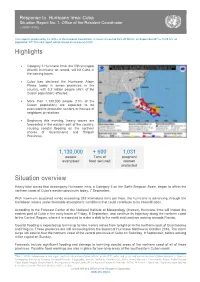

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida.