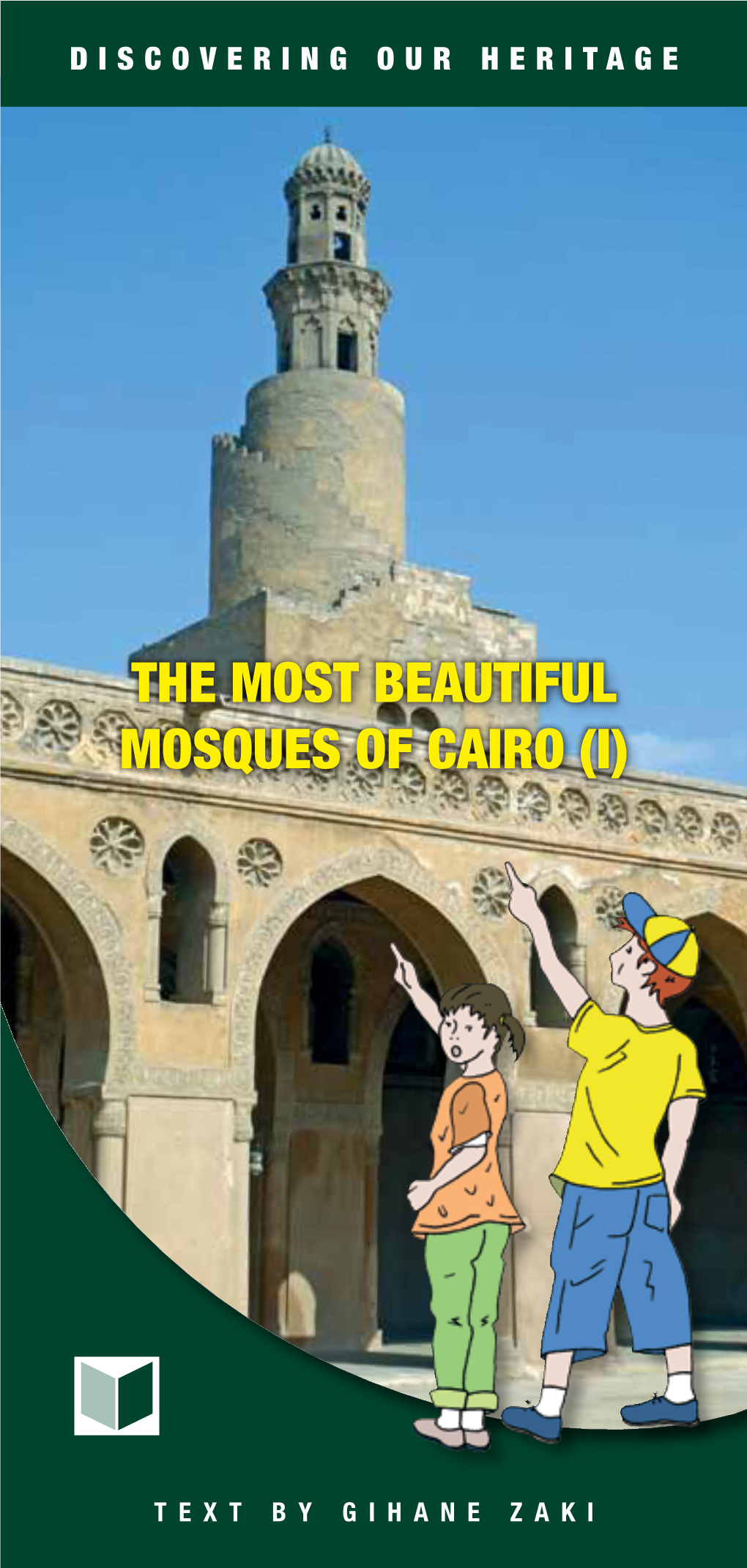

The Most Beautiful Mosques of Cairo (I)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of Islamic Geometric Patterns

Frontiers of Architectural Research (2013) 2, 243–251 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/foar RESEARCH ARTICLE Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns Yahya Abdullahin, Mohamed Rashid Bin Embi1 Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor 81310, Malaysia Received 18 December 2012; received in revised form 27 March 2013; accepted 28 March 2013 KEYWORDS Abstract Islamic geometrical This research demonstrates the suitability of applying Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) to patterns; architectural elements in terms of time scale accuracy and style matching. To this end, a Islamic art; detailed survey is conducted on the decorative patterns of 100 surviving buildings in the Muslim Islamic architecture; architectural world. The patterns are analyzed and chronologically organized to determine the History of Islamic earliest surviving examples of these adorable ornaments. The origins and radical artistic architecture; movements throughout the history of IGPs are identified. With consideration for regional History of architecture impact, this study depicts the evolution of IGPs, from the early stages to the late 18th century. & 2013. Higher Education Press Limited Company. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction three questions that guide this work are as follows. (1) When were IGPs introduced to Islamic architecture? (2) When was For centuries, Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) have been each type of IGP introduced to Muslim architects and artisans? used as decorative elements on walls, ceilings, doors, (3) Where were the patterns developed and by whom? A domes, and minarets. However, the absence of guidelines sketch that demonstrates the evolution of IGPs throughout and codes on the application of these ornaments often leads the history of Islamic architecture is also presented. -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

The Sources of Ibn Tulun's Soffit Decoration

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences The Sources of Ibn Tulun’s Soffit Decoration A Thesis Submitted to Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts by Pamela Mahmoud Azab Under the Supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane December 2015 Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis to my late mother who encouraged me to pursue my masters. Unfortunately she passed away after my first year in the program, may her soul rest in peace. For all the good souls we lost these past years, my Mum, my Mother-in-law and my sister-in-law. I would like to thank my family, my dad, my brother, my husband, my sons Omar, Karim and my little baby girl Lina. I would like to thank my advisor Dr. O’Kane for his patience and guidance throughout writing the thesis and his helpful ideas. I enjoyed Dr. O’Kane’s courses especially “The Art of the book in the Islamic world”. I enjoyed Dr. Scanlon’s courses and his sense of humor, may his soul rest in peace. I also enjoyed Dr. Chahinda’s course “Islamic Architecture in Egypt and Syria” and her field trips. I feel lucky to have attended almost all courses in the Islamic Art and Architecture field during my undergraduate and graduate years at AUC. It is an honor to have a BA and an MA in Islamic Art and Architecture. I want to thank my friends, Nahla Mesbah for her support, encouragement, and help especially with Microsoft word, couldn’t have finished without her, and Rasha Aboul- Enein for driving me to the mosque and loaning me her camera. -

Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization (JITC)

Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization (JITC) Volume 10 Issue 2, Fall 2020 pISSN: 2075-0943, eISSN: 2520-0313 Journal DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc Issue DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.102 Homepage: https://journals.umt.edu.pk/index.php/JITC Journal QR Code: Indexing Partners Comparative Study of Architecture of the Great Mosque at Article: Samarra, Iraq and Ibn Tulun Mosque at Cairo, Egypt Author(s): Zahid Tauqeer Ahmad, Seemin Aslam Published: Fall 2020 Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.102.16 QR Code: Ahmad, Zahid Tauqeer, and Seemin Aslam. "Comparative Study of Architecture of the Great Mosque at Samarra, Iraq and Ibn To cite this Tulun Mosque at Cairo, Egypt." Journal of Islamic Thought article: and Civilization 10, no. 2 (2020): 290-303. Crossref This article is open access and is distributed under the terms of Copyright Creative Commons Attribution – Share Alike 4.0 International Information: License Publisher Department of Islamic Thought and Civilization, School of Social Information: Science and Humanities, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. For more please click here Comparative Study of Architecture of the Great Mosque at Samarra, Iraq and Ibn Tūlūn Mosque at Cairo, Egypt Zahid Tauqeer Ahmad Seemin Aslam School of Architecture and Planning, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan Abstract Ever since the emergence of Islam, mosque has always been the most dominant feature in any Islamic built environment. Over the course of time, mosque architecture has gone through a process of various forms of uses and expressions in terms of its transformation. -

What Is Islamic Architecture Anyway?

What is Islamic architecture anyway? Nasser Rabbat I have been teaching Islamic architecture at MIT for the past twenty-one years. My classes have by and large attracted two types of students. There are those who see Islamic architecture as their heritage: Muslim students from abroad, Muslim- American students, and Arab-American non-Muslims. Then there are the students who imagine Islamic architecture as exotic, mysterious, and aesthetically curious, carrying the whiff of far-distant lands. They have seen it mostly in fiction (Arabian Nights for an earlier generation, Disney’s Aladdin for this one) and they are intrigued and somewhat titillated by that fiction. These two types of students are but a microcosmic – and perhaps faintly comical – reflection of the status of Islamic architecture within both academia and architectural practice today. The two dominant factions in the field are indeed the aesthetes and the partisans, although neither side would agree to those appellations. Nor would either faction claim total disengagement from each other or exclusive representation of the field. The story of their formation and rise and the trajectories they have followed is another way of presenting the evolution of Islamic architecture as a field of inquiry since the first use of the term ‘Islamic architecture’ in the early nineteenth century. This is a fascinating story in and of itself. In the present context of a volume dedicated to the historiography of Islamic art and architectural history, tracing the genesis of these two strains in the study and practice of Islamic architecture also allows me to develop my own critical position vis-à-vis the ‘unwieldy field’ of Islamic art and architecture, to use a recent controversial description.1 To begin with, the study of the architecture of the Islamic world was a post- Enlightenment European project. -

A Cosmopolitan City: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Old Cairo February 17–September 13, 2015

oi.uchicago.edu a cosmopolitan city 1 oi.uchicago.edu Exterior of a house in cairo (photo by J. Brinkmann) oi.uchicago.edu a cosmopolitan city MusliMs, Christians, and Jews in old Cairo edited by t asha vordErstrassE and tanya trEptow with new object photography by anna r. ressman and Kevin Bryce lowry oriEntal institutE musEum puBlications 38 thE oriEntal institutE of thE univErsity of chicago oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2014958594 ISBN: 978-1-61491-026-8 © 2015 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2015. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago This volume has been published in conjunction with the exhibition A Cosmopolitan City: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Old Cairo February 17–September 13, 2015 Oriental Institute Museum Publications 38 Published by The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois, 60637 USA oi.uchicago.edu Cover Illustration Fragment of a fritware bowl depicting a horse. Fustat. Early 14th century. 4.8 × 16.4 cm. OIM E25571. Catalog No. 19. Cover design by Josh Tulisiak Photography by Anna R. Ressman: Catalog Nos. 2–15, 17–23, 25–26, 30–33, 35–55, 57–63, 65–72; Figures 1.5–6, 7.1, 9.3–4 Photography by K. Bryce Lowry: Catalog Nos. 27–29, 34, and 56 Printed through Four Colour Print Group by Lifetouch, Loves Park, Illinois, USA The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Service — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Mosques Ofegypt

The Mosques of Egypt Bernard O’Kane The Mosques of Egypt Contents Preface and Acknowledgments ix Introduction xi Mosque of ‘Amr (Cairo, 641–twenty-first century) 2 Mosque of Ibn Tulun (Cairo, 876–79) 4 Mosque of al-Azhar (Cairo, 970–72 and later) 10 Mosque of al-Hakim (Cairo, 990–1013) 16 of al-Juyushi (Cairo, 1085) 22 Mashhad Three minarets: ‘Amri Mosque (Esna, 1081); al-Bahri (Shallal, eleventh century); al-Mujahadin MosqueMashhad (Asyut, 1708) 24 This edition published in 2016 by The American University in Cairo Press Mosque of Hasan ibn Salih (Bahnasa, twelfth century and later) 26 113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt 420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 Mosque of al-Aqmar (Cairo, 1125) 28 www.aucpress.com Copyright © 2016 by Bernard O’Kane Mosque of al-‘Amri (Qus, 1155–56 and later) 32 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Mosque of al-Salih Tala’i‘ (Cairo, 1160) 38 reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the Funerary Mosque of Sayyidna al-Husayn (Cairo, 1154–1873) 42 prior written permission of the publisher. Mosque of al-Lamati (Minya, 1182) 46 Exclusive distribution outside Egypt and North America by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd., Mausoleum of Imam al-Shafi‘i (Cairo, 1211) 50 6 Salem Road, London, W4 2BU Dar el Kutub No. 7232/15 Shrine of Abu’l-Hajaj (Luxor, 1850) 54 ISBN 978 977 416 732 4 Mosque of Sultan al-Zahir Baybars (Cairo, 1267–69) 56 Dar el Kutub Cataloging-in-Publication Data Funerary Complex of Sultan Qalawun (Cairo, 1283–84) 60 O’Kane, Bernard The Mosques of Egypt / Bernard O’Kane.— Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2016. -

GIPE-002860-Contents.Pdf (2.016Mb)

Heroes of the Nations A Series or Biographical Studies presenting the lives and work of certain representative histori cal characters, about whom have gathered the traditions or the nations to which they belong, and who have, in the majority or instances, been accepted as types or the several national ideals. 12°' Illustrated, cloth, each, 5/ Half Leather, gilt top, each, 6/• l'OR. rut.L UST SEE i:ND OF THIS VOLUME 1beroes of tbe 'Rations BDITBD BY IS9CI'I!n :Bbbott, m.:B. FBU.OW OF BALLIOL COLLBGBt OXPORD PAOTA DUell VI'IIIITt ONROMQUI 8l.OIIIA RUUM.-OYID, IN t.IYtAM, 111. THI: H!.RO'I DHDI AJID MMD-WON PANI aHAU. LIYL SALADIN F,-ontispitu. THE CITADEL OF CAIRO, EAST ANGLE. SALADIN. AND THE FALL OF THE KINGDOM OF JERUSALEM BY STANLEY LANE-POOLE, M.A. AUTHOR OF THE u LIPB OF STRATFORD CANNING," "TH& ART 011' TRB SARACENS n "CAJR01" "STUDIES IN A MOSQUE,'' "THB MOORS 1M SPAIN" 11 "TURKBY1 "THB BARBAKY CORSAIRS" ETC. G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS ICitW YOB.B: LONDON • 2F WllST TWBNTY-THIRD STJl.BBT 84 B&DPORD STRBBT1 STRAHD l:~c Jnidurbodur Jrcs& 1903 COYJIIGHT, 111<}8 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Eotered at Statiooers' Hall, Loodoa PREFACE. ALADIN is one of the few Oriental Personages who need no introduction to English readers. S Sir Walter Scott has performed that friendly office with the warmth and insight of apJ>~eciative genius. It was Saladin's good fortune to attract the notke not only of the great romancer, but also of King Richard, and to this accident·he partly owes the result that, instead of remaining a dry historical expression, under the Arabic style of" d-Melik en-NasirSa/ak-ed din Yusuf ibn Ayyub," he has become, by the abbrevi ated name of " Saladin," that familiar and amiable companion which is called a household word. -

The Story of Cairo

UNIVERSITY OP CAL F' N A . SAN DIEGO ^^ - - , The Story of Cairo All rights reserved The Story of Cairo by Stanley Lane-Poole Litt.D. M.A. Professor of Arabic at Trinity College Dublin London: J. M. Dent & Co. Aldine House 29 and 30 Bedford Street Co-vent Garden W.C. ^ ^ 1902 HE WHO HATH NOT SEEN CAIRO HATH NOT SEEN THE WORLD. HER SOIL is GOLD ; HER NILE is A MARVEL ; HER WOMEN ARE AS THE BRIGHT-EYED HOURJS or PARADISE ; HER HOUSES ARE PALACES, AND HER AIR is SOFT, WITH AN ODOUR ABOVE ALOES, REFRESHING THE HEART ; AND HOW SHOULD CAIRO BE OTHERWISE, WHEN SHE is THE MOTHER OF THE WORLD ? PREFACE is in the fullest sense a mediaeval city. It existence before the Middle its CAIROhad no Ages ; vigorous life as a separate Metropolis almost coincides with the arbitrary millennium of the middle period of and it still retains to this of its history ; day much mediaeval character and aspect. The aspect is chang- ing, but not the life. The amazing improvements of the past twenty years have altered the Egyptian's material condition, but scarcely as yet touched his character. We have given him public order and security, solvency without too heavy taxation, an efficient administration, even-handed justice, the means of higher education, and above all to every man his fair share of the enriching Nile, ^pvooppori; in the truest sense, without which nothing else avails. For all these, and especially the last, the peasant is grateful in his when their merits are out to but way, pointed him ; not so the Cairene. -

Jswbf80x9d.Pdf

2 CHAPTER 6 and political structure, as Tunisia and western Algeria lost much of their agricultural wealth and entered by the twelfth Central Islamic Lands century into a western rather than eastern Islamic and Mediterranean cultural sphere. During the last century of For reasons provided in the Prologue to Part II of this vol- their existence the Fatimids controlled hardly anything but ume, the presentation of the medieval arts in central Islamic- Egypt. Whether the major changes in Islamic art which they lands has been divided into two sections. had earlier set in motion were the result of their own, The first section deals with the rule of the Fatimid Mediterranean, contacts with the classical tradition or of the dynasty, which began in Ifriqiya (present-day Tunisia) upheavals which, especially in the eleventh century, affected around 908, moved its capital to Egypt in 969 under the the whole eastern Muslim world remains an open question. f leadership of the brilliant caliph al-Mu izz, and ruled from there an area of shifting frontiers which, at its time of great- Architecture and Architectural est expanse, extended from central Algeria to northern Decoration' Syria, the middle Euphrates valley, and the holy places of x\rabia. Its very diminished authority, affected by internal north africa dissensions and by the Crusades, was eliminated by Saladin in 1 171. The dynasties dependent on them vanished from The Fatimids founded their first capital at Mahdiyya on the 4 North Africa by 11 59, while Sicily had been conquered by eastern coast of Tunisia. Not much has remained of its the Normans in 1071. -

The Influence of Spolia on Islamic Architecture

M. Ali & S. Magdi, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 3 (2017) 334–343 THE INFLUENCE OF SPOLIA ON ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE M. ALI & S. MAGDI Department of Architecture, Canadian International College, Egypt. ABSTRACT Since the beginning of its long history, Egypt has continuously experienced and practised despolia- tion and looting of monuments, of its past from antiquity through the 19th century, and it is clearly visible that many Islamic monuments have been built with materials removed from ancient buildings. Also the city of Rome is built of layers and layers of history. It was this fascinating accumulation of history, literally, the accumulation of old stones in medieval buildings, which first triggered our research into the field of Spolia – i.e. the art or historical term for older building elements reused in a new context. In light of the previous context; the researchers in this paper are trying to shed light on the phenom- enon of the reusing of some architectural elements in Islamic architecture in Cairo, in order to outline the reasons for such phenomenon and its motives, and examine the types of those elements and places of their existence in Islamic architecture through examples of intact Islamic monuments in Cairo such as the Al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun Mosque. Keywords: ancient building, Ibn Qalawun mosque, Islamic architecture, reuse, Spolia 1 INTRODUCTION Cairo, still surrounded by her walls and spectacular gates, is today the most splendid city in the Islamic world. The most prestigious buildings were the work of the sultans and their emirs, but civilians also created many fine buildings.