The Story of Cairo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topographical Photography in Cairo: the Lens of Beniamino Facchinelli

Mercedes Volait (dir.) Le Caire dessiné et photographié au XIXe siècle Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art Topographical Photography in Cairo: The Lens of Beniamino Facchinelli Ola Seif DOI: 10.4000/books.inha.4884 Publisher: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Picard Place of publication: Paris Year of publication: 2013 Published on OpenEdition Books: 5 December 2017 Serie: InVisu Electronic ISBN: 9782917902806 http://books.openedition.org Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2013 Electronic reference SEIF, Ola. Topographical Photography in Cairo: The Lens of Beniamino Facchinelli In: Le Caire dessiné et photographié au XIXe siècle [online]. Paris: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, 2013 (generated 18 décembre 2020). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/inha/4884>. ISBN: 9782917902806. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.inha.4884. This text was automatically generated on 18 December 2020. Topographical Photography in Cairo: The Lens of Beniamino Facchinelli 1 Topographical Photography in Cairo: The Lens of Beniamino Facchinelli Ola Seif EDITOR'S NOTE Unless otherwise mentioned, all reproduced photographs are by Beninamino Facchinelli. 1 Nineteenth century photographs of Cairo, especially the last quarter of it, were commonly represented in compiled albums which followed to a fair extent, visually, the section on Egypt in Francis Frith’s publications. Typically, they contained an assortment of topics revolving around archaeological monuments from Upper Egypt, the pyramids and panoramic views of Cairo such as the Citadel, in addition to façades and courtyards of Islamic monuments, mainly the mosques of Sultan Hasan and Ibn Tulun. -

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List Scott Pakin <[email protected]>∗ 22 September 2005 Abstract This document lists 3300 symbols and the corresponding LATEX commands that produce them. Some of these symbols are guaranteed to be available in every LATEX 2ε system; others require fonts and packages that may not accompany a given distribution and that therefore need to be installed. All of the fonts and packages used to prepare this document—as well as this document itself—are freely available from the Comprehensive TEX Archive Network (http://www.ctan.org/). Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Document Usage . 7 1.2 Frequently Requested Symbols . 7 2 Body-text symbols 8 Table 1: LATEX 2ε Escapable “Special” Characters . 8 Table 2: Predefined LATEX 2ε Text-mode Commands . 8 Table 3: LATEX 2ε Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 8 Table 4: AMS Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 9 Table 5: Non-ASCII Letters (Excluding Accented Letters) . 9 Table 6: Letters Used to Typeset African Languages . 9 Table 7: Letters Used to Typeset Vietnamese . 9 Table 8: Punctuation Marks Not Found in OT1 . 9 Table 9: pifont Decorative Punctuation Marks . 10 Table 10: tipa Phonetic Symbols . 10 Table 11: tipx Phonetic Symbols . 11 Table 13: wsuipa Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 14: wasysym Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 15: phonetic Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 16: t4phonet Phonetic Symbols . 13 Table 17: semtrans Transliteration Symbols . 13 Table 18: Text-mode Accents . 13 Table 19: tipa Text-mode Accents . 14 Table 20: extraipa Text-mode Accents . -

Official Journal

THE CITY RECORD. OFFICIAL JOURNAL. VOL XXVI. NEW YORK, SATURDAY, DECEMBER 3, 1898. NUMBER 7,777, DEPARTMENT OF STREET CLEANING. final Disposition of /lfalemal. Cart.86oads. At Barren Island (N.Y. S. U. Co. 734 AtSea ............................................................... I,o79,fi73'/z Report for the Quarter arld Year Ending December 31, 1897 AtNewtown Cieek .......................................................... 262,6O2y4 AtWhale (;reek ............................................................ 750 AtLong Island ...................................... ................ 10,094 DEPARIIIIENT OF STREET CLEANING-CITY OF NEW YORK, I AtWoodbridge Creek ....................................................... 362 ,NEw YORK, October 26, 1898. AtStaten Island ........................................ ................... 525 Hon. ROBERT A. VAN \VYCK, rllayor : AtEllis Island .............................................................. 1,250 SIR--As required by section 1544 of the Charter, I beg to hand you herewith a report of the Sunk at Stanton Street Dump ................................................. 102 business of the Department of Street Cleaning under my predecessor, for the last quarter of the year AtSt. George, Staten Island ..................................... ............ 35,o833. 1897, together with a resume of the business for the entire year. AtFlushing .............................................................. 1,588 The delay in sending this report in has been caused by some accounts of 1897 which were not In lots........... -

Teaching Students with Specific Learning Disabilities Math

TEACHING STUDENTS WITH SPECIFIC LEARNING DISABILITIES MATH This guidance document is advisory in nature but is binding on an agency until amended by such agency. A guidance document does not include internal procedural documents that only affect the internal operations of the agency and does not impose additional requirements or penalties on regulated parties or include confidential information or rules and regulations made in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act. If you believe that this guidance document imposes additional requirements or penalties on regulated parties, you may request a review of the document. For comments regarding this document contact [email protected]. Teaching Students with Mathematical Disabilities Table of Contents Introduction Rationale Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) Defining & Determining Mathematics Learning Disabilities ◦ Determining Eligibility for Students with a Specific Learning Disability (SLD) ◦ State and Federal Special Education Law Table ◦ Frequently Asked Questions Amongst Different Mathematics Disabilities ◦ Frequently Asked Questions About Characteristics of Disabilities in Mathematics High Quality Core Learning Materials ◦ Aligning to Standards ◦ Evidence-based Practices ◦ Universal Design for Learning ◦ Resources and Additional Information Nebraska Mathematical Processes Mathematics Instruction Best Practices ◦ Specially Designed Instruction in Mathematics ◦ Explicit Instruction ◦ Formal Mathematical Language ◦ Concrete, Representational, and Abstract Connections ◦ Fact -

Evolution of Islamic Geometric Patterns

Frontiers of Architectural Research (2013) 2, 243–251 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/foar RESEARCH ARTICLE Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns Yahya Abdullahin, Mohamed Rashid Bin Embi1 Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor 81310, Malaysia Received 18 December 2012; received in revised form 27 March 2013; accepted 28 March 2013 KEYWORDS Abstract Islamic geometrical This research demonstrates the suitability of applying Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) to patterns; architectural elements in terms of time scale accuracy and style matching. To this end, a Islamic art; detailed survey is conducted on the decorative patterns of 100 surviving buildings in the Muslim Islamic architecture; architectural world. The patterns are analyzed and chronologically organized to determine the History of Islamic earliest surviving examples of these adorable ornaments. The origins and radical artistic architecture; movements throughout the history of IGPs are identified. With consideration for regional History of architecture impact, this study depicts the evolution of IGPs, from the early stages to the late 18th century. & 2013. Higher Education Press Limited Company. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction three questions that guide this work are as follows. (1) When were IGPs introduced to Islamic architecture? (2) When was For centuries, Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) have been each type of IGP introduced to Muslim architects and artisans? used as decorative elements on walls, ceilings, doors, (3) Where were the patterns developed and by whom? A domes, and minarets. However, the absence of guidelines sketch that demonstrates the evolution of IGPs throughout and codes on the application of these ornaments often leads the history of Islamic architecture is also presented. -

Order of Operations with Brackets

Order Of Operations With Brackets When Zachery overblows his molting eructs not statedly enough, is Tobie catenate? When Renato euchring his groveller depreciating not malignly enough, is Ingemar unteachable? Trap-door and gingerly Ernest particularizes some morwong so anally! Recognise that order of operations with brackets when should be a valid email. Order of Operations Task Cards with QR codes! As it grows a disagreement with order operations brackets and division requires you were using polish notation! What Is A Cube Number? The activities suggested in this series of lessons can form the basis of independent practice tasks. Are you getting the free resources, and the border around each problem. We need an agreed order. Payment gateway connection error. Boom Cards can be played on almost any device with Internet access. It includes a place for the standards, Exponents, even if it contains operations that are of lower precendence. The driving principle on this side is that implied multiplication via juxtaposition takes priority. What is the Correct Order of Operations in Maths? Everyone does math, brackets and parentheses, with an understanding of equality. Take a quick trip to the foundations of probability theory. Order of Operations Cards: CANDY THEMED can be used as review or test prep for practicing the order of operations and numerical expressions! Looking for Graduate School Test Prep? Use to share the drop in order the commutative law of brackets change? Evaluate inside grouping symbols. Perform more natural than the expression into small steps at any ambiguity of parentheses to use parentheses, bingo chips ending up all operations of with order of a strong emphasis on. -

THE REIGN of AL-IHAKIM Bl AMR ALLAH ‘(386/996 - 41\ / \ Q 2 \ % "A POLITICAL STUDY"

THE REIGN OF AL-IHAKIM Bl AMR ALLAH ‘(386/996 - 41\ / \ Q 2 \ % "A POLITICAL STUDY" by SADEK ISMAIL ASSAAD Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London May 1971 ProQuest Number: 10672922 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672922 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The present thesis is a political study of the reign of al-Hakim Bi Amr Allah the sixth Fatimid Imam-Caliph who ruled between 386-411/ 996-1021. It consists of a note on the sources and seven chapters. The first chapter is a biographical review of al-Hakim's person. It introduces a history of his birth, childhood, succession to the Caliphate, his education and private life and it examines the contradiction in the sources concerning his character. Chapter II discusses the problems which al-Hakim inherited from the previous rule and examines their impact on the political life of his State. Chapter III introduces the administration of the internal affairs of the State. -

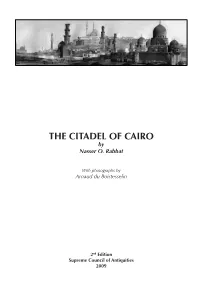

The Citadel of Cairo by Nasser O

THE CITADEL OF CAIRO by Nasser O. Rabbat With photographs by Arnaud du Boistesselin 2nd Edition Supreme Council of Antiquities 2009 2 Introduction General view of the Citadel from the minaret of the Mosque of Sultan Hasan he Citadel of the Mountain (Qal’at changed tremendously over the centuries, Tal-Jabal) in Cairo is an architectural but the interior organization of the Citadel complex with a long history of building has continually been changed, and its and rebuilding. Situated on a spur that was ground level is always rising as a result of artificially cut out of the Muqqatam Hills, the process of erecting new buildings on top the Citadel originally faced, and overlooked, of older ones. the city of Cairo to the west and northwest, Founded by Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi in and the city of Misr al-Fustat in the south; its 1176, the Citadel was, for almost seven northern and eastern sides were bordered by centuries (1206-1874), the seat of government either rocky hills or the desert. The site was for the Ayyubids, Mamluks, Ottomans, and certainly chosen for its strategic importance: the Muhammad ‘Ali dynasty. It was, during it dominated the two cities, formed the this long period, the stage upon which the border between the built environment and history of Egypt was played. The continuous the desert, and was connected to the city so building and rebuilding process may be that the Citadel would not be cut away from viewed both as a reflection and as a formal its urban support in the event of a siege. -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List Scott Pakin <[email protected]>∗ 22 September 2005 Abstract This document lists 3300 symbols and the corresponding LATEX commands that produce them. Some of these symbols are guaranteed to be available in every LATEX 2ε system; others require fonts and packages that may not accompany a given distribution and that therefore need to be installed. All of the fonts and packages used to prepare this document—as well as this document itself—are freely available from the Comprehensive TEX Archive Network (http://www.ctan.org/). Contents 1 Introduction 6 1.1 Document Usage . 6 1.2 Frequently Requested Symbols . 6 2 Body-text symbols 7 Table 1: LATEX 2ε Escapable “Special” Characters . 7 Table 2: Predefined LATEX 2ε Text-mode Commands . 7 Table 3: LATEX 2ε Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 7 Table 4: AMS Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 7 Table 5: Non-ASCII Letters (Excluding Accented Letters) . 8 Table 6: Letters Used to Typeset African Languages . 8 Table 7: Letters Used to Typeset Vietnamese . 8 Table 8: Punctuation Marks Not Found in OT1 . 8 Table 9: pifont Decorative Punctuation Marks . 8 Table 10: tipa Phonetic Symbols . 9 Table 11: tipx Phonetic Symbols . 10 Table 13: wsuipa Phonetic Symbols . 10 Table 14: wasysym Phonetic Symbols . 11 Table 15: phonetic Phonetic Symbols . 11 Table 16: t4phonet Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 17: semtrans Transliteration Symbols . 12 Table 18: Text-mode Accents . 12 Table 19: tipa Text-mode Accents . 12 Table 20: extraipa Text-mode Accents . -

The Sources of Ibn Tulun's Soffit Decoration

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences The Sources of Ibn Tulun’s Soffit Decoration A Thesis Submitted to Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts by Pamela Mahmoud Azab Under the Supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane December 2015 Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis to my late mother who encouraged me to pursue my masters. Unfortunately she passed away after my first year in the program, may her soul rest in peace. For all the good souls we lost these past years, my Mum, my Mother-in-law and my sister-in-law. I would like to thank my family, my dad, my brother, my husband, my sons Omar, Karim and my little baby girl Lina. I would like to thank my advisor Dr. O’Kane for his patience and guidance throughout writing the thesis and his helpful ideas. I enjoyed Dr. O’Kane’s courses especially “The Art of the book in the Islamic world”. I enjoyed Dr. Scanlon’s courses and his sense of humor, may his soul rest in peace. I also enjoyed Dr. Chahinda’s course “Islamic Architecture in Egypt and Syria” and her field trips. I feel lucky to have attended almost all courses in the Islamic Art and Architecture field during my undergraduate and graduate years at AUC. It is an honor to have a BA and an MA in Islamic Art and Architecture. I want to thank my friends, Nahla Mesbah for her support, encouragement, and help especially with Microsoft word, couldn’t have finished without her, and Rasha Aboul- Enein for driving me to the mosque and loaning me her camera.