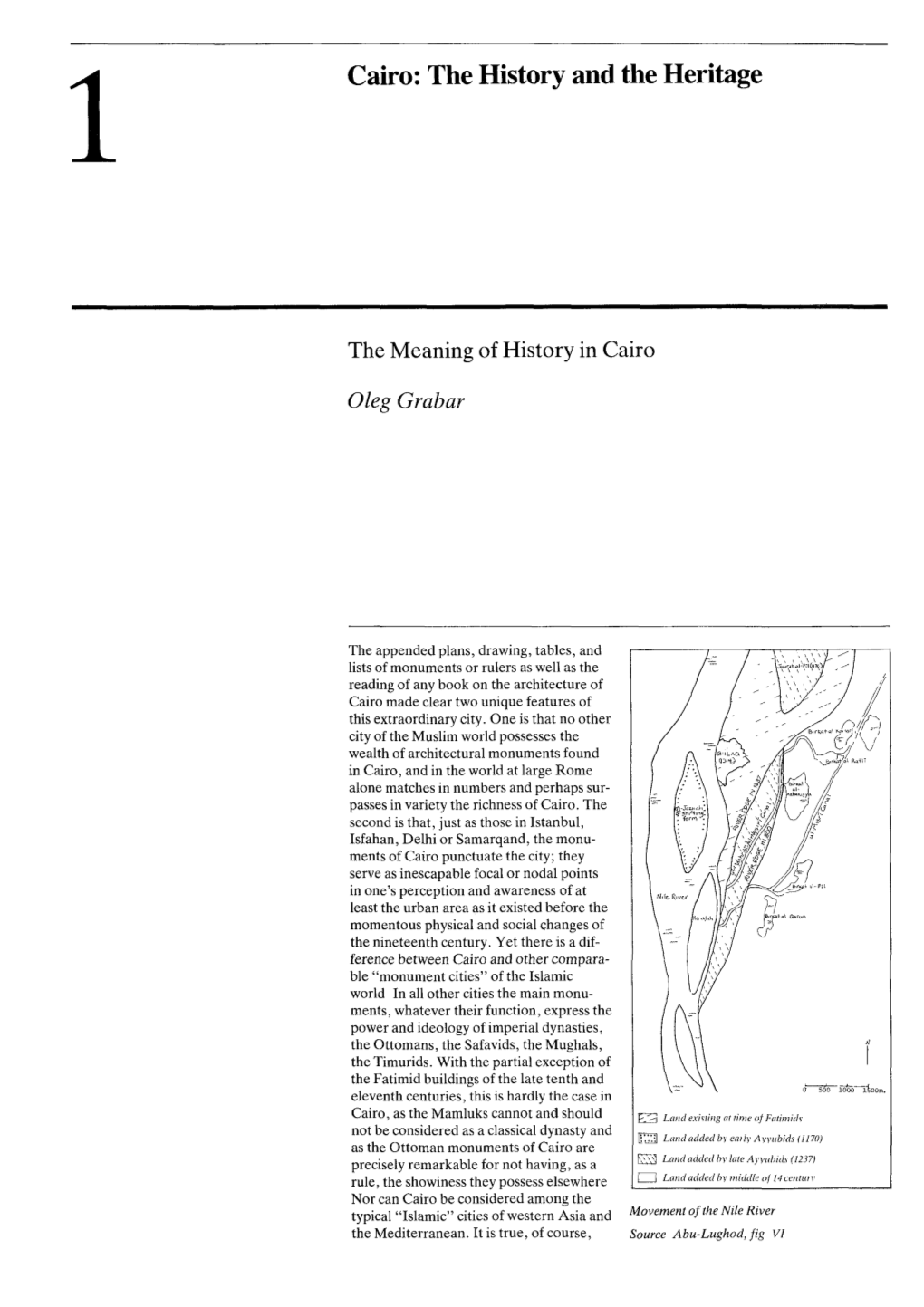

Cairo: the History and the Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval History

CONTENTS MEDIEVAL HISTORY 1. MAJOR DYNASTIES (EARLY ....... 01-22 2. EARLY MUSLIM INVASIONS ........23-26 MEDIEVAL INDIA 750-1200 AD) 2.1 Early Muslim Invasions ..................24 1.1 Major Dynasties of North ...............02 The Arab Conquest of Sindh ............... 24 India (750-1200 Ad) Mahmud of Ghazni ............................ 24 Introduction .......................................2 Muhammad Ghori ............................. 25 The Tripartite Struggle ........................2 th th The Pratiharas (8 to 10 Century) ........3 3. THE DELHI SULTANATE ................27-52 th th The Palas (8 to 11 Century) ...............4 (1206-1526 AD) The Rashtrakutas (9th to 10th Century) ....5 The Senas (11th to 12th Century) ............5 3.1 The Delhi Sultanate ......................28 The Rajaputa’s Origin ..........................6 Introduction ..................................... 28 Chandellas ........................................6 Slave/Mamluk Dynasty (Ilbari ............ 28 Chahamanas ......................................7 Turks)(1206-1526 AD) Gahadvalas ........................................8 The Khalji Dynasty (1290-1320 AD) ..... 32 Indian Feudalism ................................9 The Tughlaq Dynasty (1320-1414 AD) .. 34 Administration in Northern India ........ 09 The Sayyid Dynasty ........................... 38 between 8th to 12th Century Lodi Dynasty .................................... 38 Nature of Society .............................. 11 Challenges Faced by the Sultanate ...... 39 Rise -

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

A New Path to Urban Rehabilitation in Cairo

A New Path to Urban Rehabilitationin Cairo STEFANO BIANCA, DIRECTOR, HISTORIC CITIES SUPPORT PROGRAMME xposed as they are to ever increasing pressures of modern urban development and to creep- ing globalised uniformity, the historic cities of the Islamic world represent a rich cultural legacy worth preserving as a reference and source of inspiration for future generations. Un- like most of their Western counterparts, many of them managed to survive as authentic living cities, in spite of physical decline and economic depression. Their skilfully adorned monuments, whether made of stone, brick or timber, carry the imprint of timeless spiritual messages which still speak to present users. The cohesive patterns of their historic urban fabric embody meaningful modes of so- cial interaction and tangible environmental qualities, which transmit the experience of past gener- ations and are still able to shape and support contemporary community life; for the values inherent to their spatial configurations transcend short-lived changes and fashions. Such contextual values, sadly absent in most of our planned modern towns, constitute the cul- tural essence of historic cities. To use an analogy from literature, the qualitative rapport between single components has the power to transform a series of words into significant information or, even better, to make the difference between 'prose' and 'poetry'. This is why a city can become a collective work of art, or rather a living cultural experience, perpetuated by means of social rit- uals and local myths and tales. Cairo, in particular, is engraved in the cultural memory of Muslim visitors, readers, and listeners. Since medieval times, prominent travellers such as Nasir- i-Khosraw, Ibn Jubayr and Ibn Battuta have praised its splendours.' The endless flow of stories contained in The Thousandand One Nights features Cairo, together with Baghdad, as the most re- current backdrop for all sorts of experiences and adventures. -

Islamic Civilisation in the Mediterranean Nicosia, I-4 December 2010

IRCICA RESEARCH CENTRE FOR ISLAM lC HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Proceedings of the International Conference on Islamic Civilisation in the Mediterranean Nicosia, ı-4 December 2010 Akdeniz'de İslam Medeniyeti Milletlerarası Konferans Tebliğleri Lefkoşa, ı -4 Aralık 20 ı o Türkiye Dlyanet Vakfı .. \ . Islam Araştımıaları Met'k.ezi Kü'rtlphanesi Tas. No: İstanbul2013 The Blazon Western lnfluences on Mamluk Art after the Crusades Sumiyo Okumura* In Mamluk art, w e often see rounded or oval shaped ran k/ runuk (emblems, blazons or coats-of-arms), which are decorated with differentkinds ofheraldic symbols. They were use d by Mamluk amirs to identify the passessors and their status in the structure of Mamluk government. Although many important studies have been conducted on this subject, 1 histarical documents do not give much information ab out the origin of Mamluk emblems. There existed many kinds of emblems that indicated occupations including saqi (cup bearer) with the cup (Fig. 1); dawadar (inkwell holder the secretary or officer) with the pen box (Fig. 2); and djamdar (master of the robe keeper of clothes) with the shape of napkin, barfcP (postman, courier) with straight lines, jukandaf3 (çevgandar = holder of polo stick) with a hall and polo stick, and silahdar (swoi:d bearer) was symbolized with the sword (Fig. 3). The Ayyubid Sultan, Melikü's-Salih Najim al-Din Ayyub (r. 1240-1249) bestawed the emblem of a smail dining table, called Honca 1 Han çe, 4 on an amir who was appointed to the position of jashnkir. Jashnkir was the taster of the Sultan's food and drink. -

The Introduction of a Contemporary Building Into a Historic Fabric

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2000 The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric Gregory John Saldaña University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Saldaña, Gregory John, "The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric" (2000). Theses (Historic Preservation). 423. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/423 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Saldaña, Gregory John (2000). The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/423 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Saldaña, Gregory John (2000). The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/423 piPK^I!^!^^ ;^-"v \^««> r.A <^'{5^ -;>• i' W 'if UNIVERSITY^ PENNSYLVANIA. UBRARIE5 THE INTRODUCTION OF A CONTEMPORARY BUILDING INTO A HISTORIC FABRIC Gregory John Saldana A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2000 N^1_.^>,LjL->--v->^ isor eadCT David De Long FhsikiS. -

FSF #4 Low Res

Bulletin 1, January, 2015 Bulletin 4, October, 2015 North Africa Horizons NorthNorth AfricaAfrica HorizonsHorizons A monitoring bulletinA monitoring published bulletin by FSF published (Futures by Studies FSF (Futures Forum Studiesfor Africa Forum and the for MiddleAfrica and East) the Middle East) Future of North Africa's Slums: "Slums ofSECURING Hope" or "Slums of Despair"? WHEAT AVAILABILITY What Prospects for North Africa? http://www.foresightfordevelopment.org/fsf/all-pages http://www.foresightfordevelopment.org/fsf/all-pages Contents Introduction 1 Editorial 2 Urbanization and Future Prospects of Slums in NA 5 The Slum Economy:The Base of the Pyramid that Holds The Formal City 14 Building Resilience of Slum Communities 22 Future of North Africa's Slums: "Slums of Hope" or "Slums of Despair"? Introduction For decades, urbanization was probably the most visible future trend and the easiest to forecast. We now know that the future is urban and glimpses of the future can be seen already in North Africa (NA), where some countries are over 80% urbanized. However, the nature of this future is contested. While urban planners look to Dubai and other shiny cities as the model for the future, the realities are very different as most cities in NA have already formed their character; and to many this portrait is ugly and dysfunctional. Indeed many cities are teaming with slums and despite concerted efforts over the years to rid NA cities of slums, they continue to be pervasive future of the city. Slums are the entry point to address the cities’ challenges and there is a need to realize that as long as the urbanization process continues there will never be enough resources to provide decent housing for all. -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

CAIRO T E N a L 109 P Y L E N Park O L

© Lonely Planet 109 Cairo CAIRO Let’s address the drawbacks first. The crowds on a Cairo footpath make Manhattan look like a ghost town. You will be hounded by papyrus sellers at every turn. Your life will flash before your eyes each time you venture across a street. And your snot will run black from the smog. But it’s a small price to pay to visit the city Cairenes call Umm ad-Dunya – the Mother of the World. This city has an energy, palpable even at three in the morning, like no other. It’s the product of its 20 million inhabitants waging a battle against the desert and winning (mostly), of 20 million people simultaneously crushing the city’s infrastructure under their collective weight and lifting the city’s spirit up with their uncommon graciousness and humour. One taxi ride can span millennia, from the resplendent mosques and mausoleums built at the pinnacle of the Islamic empire, to the 19th-century palaces and grand avenues (which earned the city the nickname ‘Paris on the Nile’), to the brutal concrete blocks of the Nasser years – then all the way back to the days of the pharaohs, as the Pyramids of Giza hulk on the western edge of the city. The architectural jumble is smoothed over by an even coating of beige sand, and the sand is a social equaliser as well: everyone, no matter how rich, gets dusty when the spring khamsin blows in. So blow your nose, crack a joke and learn to look through the dirt to see the city’s true colours. -

Urban Rehabilitation and Community Developmentin Al-Darbal-Ahmar FRANCESCO SIRAVO

Urban Rehabilitation and Community Developmentin al-Darbal-Ahmar FRANCESCO SIRAVO T|he - work on the park and the historic wall along the critical western edge of the Darassa site raised the issue of how best to harness the dynamics unleashed by the park project on- to the adjacent urban area of al-Darb al-Ahmar, a densely built-up district of historic Cairo. The area lies south of the prestigious al-Azhar Mosque and the popular Khan al-Khalili, historic Cairo's principal tourist bazaar, and is bound by al-Azhar Street, the Darassa Hills and al-Darb al-Ahmar Street. Today, the area is the focus of much public interest, and is on the verge of major changes induced by a number of large-scale projects, including the recent completion of the Azhar Street tunnel, the planned pedestrian square between al-Azhar and al-Hussein, the de- velopment of new parking and commercial facilities on the 'Urban Plaza' site, and, lastly, the cre- ation of the new Azhar Park on top of the Darassa Hills, a strategic location between the Fatimid city, the Mamluk cemeteries and the Citadel. These developments will dramatically improve the image and importance of al-Darb al-Ahmar over the next several years and call for a carefully stud- ied urban plan of action to guide future interventions in the district. RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES A vital residential district with many artisans, small enterprises and a strong social cohesion, al- Darb al-Ahmar suffers today from poverty, inadequate infrastructure and a lack of community services. Although endowed with sixty-five registered monuments and several hundred historic buildings, its residential building stock is in very poor condition due to the area's low family in- comes and an economic base that often lags behind other parts of Cairo. -

1 Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title The slave dynasty (1206-1290) Module Id I C/ OIH/ 20 Knowledge in Medieval Indian History and Delhi Pre-requisites Sultanate To know the History of Slave/ Mamluk dynasty Objectives and their role in Delhi sultanate Qutb-ud-din Aibak / Iltutmish/ Razia / Balban / Keywords Slave / Mamluk / Delhi Sultanate E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Introduction The Sultanate of Delhi, said to have been formally founded by Qutb-ud-din Aibak, one of the Viceroys of Muhammad Ghori. It is known as the Sultanate of Delhi because during the greater part of the Sultanate, its capital was Delhi. The Sultanate of Delhi (1206–1526) had five ruling dynasties viz., 1) The Slave dynasty (1206-1290), 2) The Khilji Dynasty (1290–1320) 3), The Tughlaq Dynasty (1320–1414), 4) The Sayyad Dynasty (1414–1451) and 5) The Lodi dynasty (1451–1526). The first dynasty of the Sultanate has been designated by various historians as ‘The Slave’, ‘The Early Turk’, ‘The Mamluk’ and ‘The Ilbari’ 2. Slave/Mamluk Dynasty 2.1. Qutb-ud-din Aibak (1206 – 1210) Qutb-ud-din Aibak was the founder of the Slave/Mamluk dynasty. He was the Turk of the Aibak tribe. In his childhood he was first purchased by a kind hearted Qazi of Nishapur as Slave. He received education in Islamic theory and swordmanship along with the son of his master. When Qazi died, he was sold by his son to a merchant who took him to Ghazni where he was purchased by Muhammad Ghori. -

Evolution of Islamic Geometric Patterns

Frontiers of Architectural Research (2013) 2, 243–251 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/foar RESEARCH ARTICLE Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns Yahya Abdullahin, Mohamed Rashid Bin Embi1 Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor 81310, Malaysia Received 18 December 2012; received in revised form 27 March 2013; accepted 28 March 2013 KEYWORDS Abstract Islamic geometrical This research demonstrates the suitability of applying Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) to patterns; architectural elements in terms of time scale accuracy and style matching. To this end, a Islamic art; detailed survey is conducted on the decorative patterns of 100 surviving buildings in the Muslim Islamic architecture; architectural world. The patterns are analyzed and chronologically organized to determine the History of Islamic earliest surviving examples of these adorable ornaments. The origins and radical artistic architecture; movements throughout the history of IGPs are identified. With consideration for regional History of architecture impact, this study depicts the evolution of IGPs, from the early stages to the late 18th century. & 2013. Higher Education Press Limited Company. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction three questions that guide this work are as follows. (1) When were IGPs introduced to Islamic architecture? (2) When was For centuries, Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) have been each type of IGP introduced to Muslim architects and artisans? used as decorative elements on walls, ceilings, doors, (3) Where were the patterns developed and by whom? A domes, and minarets. However, the absence of guidelines sketch that demonstrates the evolution of IGPs throughout and codes on the application of these ornaments often leads the history of Islamic architecture is also presented. -

Enabling Rooted History: a Synopsis of Medieval Cairo Yasser M

Enabling Rooted History: A Synopsis of Medieval Cairo Yasser M. Ayad 2013 ESRIUC – San Diego, CA July 8-12, 2013 Enabling Rooted History: A Synopsis of Medieval Cairo Yasser Ayad - Clarion University of PA Abstract During the period of middle ages, the Islamic Empire reached its peak and art and architecture flourished to a great extent. Egypt in general and Cairo in specific was sometimes marginalized in history, but it was also glorified in other periods. This was mainly dependent on the interest of the ruling power at the time. The current work is an attempt to link literary work with spaces in the historical Islamic district in Cairo. It presents dynasty successions and their main characteristics in the location, design, art and architecture of the city. It also extends to cover a review of the available online resources of historic Cairo and the efforts towards the development of an interactive atlas of the city’s spaces and places. Introduction Egypt is known with its wealth of historical monuments representing great civilizations that inhabited its land for thousands of years. For the western casual tourist, visiting Egypt means the indulgence in its Pharos civilization, old Egyptian customs and stories that do not necessarily constitute any importance in the shaping up of contemporary Egypt. This paper is concerned with bringing to light an era that touches modern Egyptians who are nowadays living its continuum. Not necessarily in its same exact shape or form, but in a very similar manner, and in many cases, in the same places, structures and spaces. It is the era that is well known to the west as the "dark ages".