Staging the City: Or How Mamluk Architecture Coopted the Streets of Cairo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

A New Path to Urban Rehabilitation in Cairo

A New Path to Urban Rehabilitationin Cairo STEFANO BIANCA, DIRECTOR, HISTORIC CITIES SUPPORT PROGRAMME xposed as they are to ever increasing pressures of modern urban development and to creep- ing globalised uniformity, the historic cities of the Islamic world represent a rich cultural legacy worth preserving as a reference and source of inspiration for future generations. Un- like most of their Western counterparts, many of them managed to survive as authentic living cities, in spite of physical decline and economic depression. Their skilfully adorned monuments, whether made of stone, brick or timber, carry the imprint of timeless spiritual messages which still speak to present users. The cohesive patterns of their historic urban fabric embody meaningful modes of so- cial interaction and tangible environmental qualities, which transmit the experience of past gener- ations and are still able to shape and support contemporary community life; for the values inherent to their spatial configurations transcend short-lived changes and fashions. Such contextual values, sadly absent in most of our planned modern towns, constitute the cul- tural essence of historic cities. To use an analogy from literature, the qualitative rapport between single components has the power to transform a series of words into significant information or, even better, to make the difference between 'prose' and 'poetry'. This is why a city can become a collective work of art, or rather a living cultural experience, perpetuated by means of social rit- uals and local myths and tales. Cairo, in particular, is engraved in the cultural memory of Muslim visitors, readers, and listeners. Since medieval times, prominent travellers such as Nasir- i-Khosraw, Ibn Jubayr and Ibn Battuta have praised its splendours.' The endless flow of stories contained in The Thousandand One Nights features Cairo, together with Baghdad, as the most re- current backdrop for all sorts of experiences and adventures. -

Harry-Potter-Clue-Rules.Pdf

AGES 9+ 3-5 Players shows the Dark Mark – take a Check this card off on your 5. Make an Accusation card from the Dark Deck and If all players run out of house • If you are in a room at the notepad – this proves the How to Play – read it out loud. points before the game is end of one turn, you must card is not in the envelope. When you’re sure you’ve solved At a Glance over, the Dark Forces have leave it on your next turn. Your turn is now over. the mystery, use your roll to get Each Dark card describes won and the missing student You may not re-enter the to Dumbledore’s office as fast as On each turn: an event likely to have been meets an unfortunate end! same room on that turn. • If the player to your left does you can. From here, you can make caused by Dark Forces and each not have any of the Mystery your accusation by naming the 1. Roll card shows: • You cannot pass through a cards you suggested, the player suspect, item and location you 3. Move closed door unless you have to their left must show a card think are correct. For example: 2. Check the Hogwarts die • What is happening an Alohomora Help card. if they have one. Keep going 3. Move (using the other dice Check the two normal dice. until a player shows you a “I accuse Dolores Umbridge with or a secret passage) • Who is affected You can either: card or until all players have the Sleeping Draught in the Great 4. -

The Traditional Arts and Crafts of Turnery Or Mashrabiya

THE TRADITIONAL ARTS AND CRAFTS OF TURNERY OR MASHRABIYA BY JEHAN MOHAMED A Capstone submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Art Graduate Program in Liberal Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Martin Rosenberg And Approved by ______________________________ Dr. Martin Rosenberg Camden, New Jersey May 2015 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT The Traditional Arts and Crafts of Turnery or Mashrabiya By JEHAN MOHAMED Capstone Director: Dr. Martin Rosenberg For centuries, the mashrabiya as a traditional architectural element has been recognized and used by a broad spectrum of Muslim and non-Muslim nations. In addition to its aesthetic appeal and social component, the element was used to control natural ventilation and light. This paper will analyze the phenomenon of its use socially, historically, artistically and environmentally. The paper will investigate in depth the typology of the screen; how the different techniques, forms and designs affect the function of channeling direct sunlight, generating air flow, increasing humidity, and therefore, regulating or conditioning the internal climate of a space. Also, in relation to cultural values and social norms, one can ask how the craft functioned, and how certain characteristics of the mashrabiya were developed to meet various needs. Finally, the study of its construction will be considered in relation to artistic representation, abstract geometry, as well as other elements of its production. ii Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………….……….…..ii List of Illustrations………………………………………………………………………..iv Introduction……………………………………………….…………………………….…1 Chapter One: Background 1.1. Etymology………………….……………………………………….……………..3 1.2. Description……………………………………………………………………...…6 1.3. -

The Political Economy of the New Egyptian Republic

ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﻓﻲ اﻟﻌﻠﻮم اﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ Hopkins The Political Economy of اﻹﻗﺘﺼﺎد اﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﻰ the New Egyptian Republic ﻟﻠﺠﻤﻬﻮرﻳﺔ اﳉﺪﻳﺪة ﻓﻰ ﻣﺼﺮ The Political Economy of the New Egyptian of the New Republic Economy The Political Edited by ﲢﺮﻳﺮ Nicholas S. Hopkins ﻧﻴﻜﻮﻻس ﻫﻮﺑﻜﻨﺰ Contributors اﳌﺸﺎرﻛﻮن Deena Abdelmonem Zeinab Abul-Magd زﻳﻨﺐ أﺑﻮ اﻟﺪ دﻳﻨﺎ ﻋﺒﺪ اﳌﻨﻌﻢ Yasmine Ahmed Sandrine Gamblin ﺳﺎﻧﺪرﻳﻦ ﺟﺎﻣﺒﻼن ﻳﺎﺳﻤﲔ أﺣﻤﺪ Ellis Goldberg Clement M. Henry ﻛﻠﻴﻤﻨﺖ ﻫﻨﺮى إﻟﻴﺲ ﺟﻮﻟﺪﺑﻴﺮج SOCIAL SCIENCE IN CAIRO PAPERS Dina Makram-Ebeid Hans Christian Korsholm Nielsen ﻫﺎﻧﺰ ﻛﺮﻳﺴﺘﻴﺎن ﻛﻮرﺷﻠﻢ ﻧﻴﻠﺴﻦ دﻳﻨﺎ ﻣﻜﺮم ﻋﺒﻴﺪ David Sims دﻳﭭﻴﺪ ﺳﻴﻤﺰ Volume ﻣﺠﻠﺪ 33 ٣٣ Number ﻋﺪد 4 ٤ ﻟﻘﺪ اﺛﺒﺘﺖ ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﻓﻰ اﻟﻌﻠﻮم اﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ أﻧﻬﺎ ﻣﻨﻬﻞ ﻻ ﻏﻨﻰ ﻋﻨﻪ ﻟﻜﻞ ﻣﻦ اﻟﻘﺎرئ اﻟﻌﺎدى واﳌﺘﺨﺼﺺ ﻓﻰ ﺷﺌﻮن CAIRO PAPERS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE is a valuable resource for Middle East specialists اﻟﺸﺮق اﻷوﺳﻂ. وﺗﻌﺮض ﻫﺬه اﻟﻜﺘﻴﺒﺎت اﻟﺮﺑﻊ ﺳﻨﻮﻳﺔ - اﻟﺘﻰ ﺗﺼﺪر ﻣﻨﺬ ﻋﺎم ١٩٧٧ - ﻧﺘﺎﺋﺞ اﻟﺒﺤﻮث اﻟﺘﻰ ﻗﺎم ﺑﻬﺎ ﺑﺎﺣﺜﻮن and non-specialists. Published quarterly since 1977, these monographs present the results of ﻣﺤﻠﻴﻮن وزاﺋﺮون ﻓﻰ ﻣﺠﺎﻻت ﻣﺘﻨﻮﻋﺔ ﻣﻦ اﳌﻮﺿﻮﻋﺎت اﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﻴﺔ واﻻﻗﺘﺼﺎدﻳﺔ واﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ واﻟﺘﺎرﻳﺨﻴﺔ ﺑﺎﻟﺸﺮق اﻷوﺳﻂ. ,current research on a wide range of social, economic, and political issues in the Middle East وﺗﺮﺣﺐ ﻫﻴﺌﺔ ﲢﺮﻳﺮ ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﺑﺎﳌﻘﺎﻻت اﳌﺘﻌﻠﻘﺔ ﺑﻬﺬه اﻟﺎﻻت ﻟﻠﻨﻈﺮ ﻓﻰ ﻣﺪى ﺻﻼﺣﻴﺘﻬﺎ ﻟﻠﻨﺸﺮ. وﻳﺮاﻋﻰ ان ﻳﻜﻮن اﻟﺒﺤﺚ .and include historical perspectives ﻓﻰ ﺣﺪود ١٥٠ ﺻﻔﺤﺔ ﻣﻊ ﺗﺮك ﻣﺴﺎﻓﺘﲔ ﺑﲔ اﻟﺴﻄﻮر، وﺗﺴﻠﻢ ﻣﻨﻪ ﻧﺴﺨﺔ ﻣﻄﺒﻮﻋﺔ وأﺧﺮى ﻋﻠﻰ اﺳﻄﻮاﻧﺔ ﻛﻤﺒﻴﻮﺗﺮ (ﻣﺎﻛﻨﺘﻮش Submissions of studies relevant to these areas are invited. Manuscripts submitted should be أو ﻣﻴﻜﺮوﺳﻮﻓﺖ وورد). أﻣﺎ ﺑﺨﺼﻮص ﻛﺘﺎﺑﺔ اﳌﺮاﺟﻊ، ﻓﻴﺠﺐ ان ﺗﺘﻮاﻓﻖ ﻣﻊ اﻟﺸﻜﻞ اﳌﺘﻔﻖ ﻋﻠﻴﻪ ﻓﻰ ﻛﺘﺎب ”اﻻﺳﻠﻮب ﳉﺎﻣﻌﺔ around 150 doublespaced typewritten pages in hard copy and on disk (Macintosh or Microsoft ﺷﻴﻜﺎﻏﻮ“ (The Chicago Manual of Style) ﺣﻴﺚ ﺗﻜﻮن اﻟﻬﻮاﻣﺶ ﻓﻰ ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ ﻛﻞ ﺻﻔﺤﺔ، أو اﻟﺸﻜﻞ اﳌﺘﻔﻖ ﻋﻠﻴﻪ ﻓﻰ Word). -

Timeline / 600 to 1700 / EGYPT

Timeline / 600 to 1700 / EGYPT Date Country | Description 619 A.D. Egypt Egypt, Jerusalem and Damascus come under the rule of the Persian Emperor Xerxes II. 627 A.D. Egypt Prophet Muhammad sends a letter to Cyrus, the Byzantine Patriarch of Alexandria and ruler of Egypt, inviting him to accept Islam. Cyrus sends gifts to the Prophet in answer, together with two sisters from Upper Egypt. The Prophet married one of them, called Maria the Copt. She bore him his only son, who died in boyhood. 639 A.D. Egypt The first mosque in Egypt is built in Bilbis, east of the Delta, to honour the martyrs and 120 companions of the Prophet who died in battle there during the Arab invasion of Egypt. It followed the ground plan of the Prophet's mosque in Medina. 641 A.D. Egypt Babylon (the Roman settlement south of present-day Cairo) capitulates to the Muslim armies led by Amr ibn al-'As.The first Islamic capital of Egypt, Fustat, is founded. 655 A.D. Egypt Ali ibn Abi Talib, the Prophet's cousin and companion, isappointed wali (ruler) of Egypt by ‘Uthman ibn ‘Affan, the third Righteous Caliph. 750 A.D. Egypt Egypt comes under the control of the Abbasid Caliphate and al-Askar, the second Islamic capital of Egypt, is founded. Marwan ibn Muhammad, the last Umayyad Caliph in the East, is murdered in Abu Seir, Fayyum, west of the Delta. 764 A.D. Egypt A great famine strikes the country due to the low Nile flood, during the rule of Amir Yazid ibn Hakim al-Mahdi, ruler of the Abbasids. -

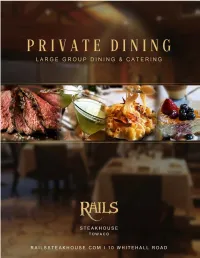

Private Dining [email protected]

LARGE GROUP DINING & CATERING Pat Leone, Director of Private Dining [email protected] Rails Steakhouse 10 Whitehall Road Towaco, NJ 07082 973.487.6633 cell / text 973.335.0006 restaurant 2 Updated 8/2/2021 PRIVATE DINI NG P L A N N I N G INFORMATION RAILS STEAKHOUSE IS LOCATED IN MORRIS COUNTY IN THE HEART ROOM ASSIGNMENTS OF MONTVILLE TOWNSHIP AND RANKS AMONG THE TOP ROOMS ARE RESERVED ACCORDING TO THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE STEAKHOUSES IN NEW JERSEY. RAILS IS KNOWN FOR USDA PRIME ANTICIPATED AT THE TIME OF THE BOOKING. ROOM FEES ARE AND CAB CORN-FED BEEF, DRY-AGED 28-30 DAYS ON PREMISE IN APPLICABLE IF GROUP ATTENDANCE DROPS BELOW THE ESTIMATED OUR DRY AGING STEAK ROOM, AND AN AWARD WINNING WINE ATTENDANCE AT THE TIME OF BOOKING. RAILS RESERVES THE LIST RECOGNIZED BY WINE SPECTATOR FIVE CONSECTUTIVE YEARS. RIGHT TO CHANGE ROOMS TO A MORE SUITABLE SIZE, WITH NOTIFICATION, IF ATTENDANCE DECREASES OR INCREASES. DINING AT RAILS THE INTERIOR DESIGN IS BREATHTAKING - SPRAWLING TIMBER, EVENT ARRANGEMENTS NATURAL STONE WALLS, GLASS ACCENTS, FIRE AND WATER TO ENSURE EVERY DETAIL IS HANDLED IN A PROFESSIONAL FEATURES. GUESTS ARE INVITED TO UNWIND IN LEATHER MANNER, RAILS REQUIRES THAT YOUR MENU SELECTIONS AND CAPTAIN'S CHAIRS AND COUCHES THAT ARE ARRANGED TO INSPIRE SPECIFIC NEEDS BE FINALIZED 3 WEEKS PRIOR TO YOUR FUNCTION. CONVERSATION IN ONE OF THREE LOUNGES. AT THAT POINT YOU WILL RECEIVE A COPY OF OUR BANQUET EVENT ORDER ON WHICH YOU MAY MAKE ADDITIONS AND STROLL ALONG THE CATWALK AND EXPLORE RAFTER'S LOUNGE DELETIONS AND RETURN TO US WITH YOUR CONFIRMING AND THE MOSAIC ROOM. -

Locating Masculinities from the Gothic Novel to Henry James

Gero Bauer Houses, Secrets, and the Closet Lettre Gero Bauer is a research fellow at the Center for Gender and Diversity Research, University of Tübingen. His academic interests include gender and queer stu- dies, and European literary and cultural history. Gero Bauer Houses, Secrets, and the Closet Locating Masculinities from the Gothic Novel to Henry James An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-3468-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivs 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non- commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contac- ting [email protected] © 2016 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover -

The Introduction of a Contemporary Building Into a Historic Fabric

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2000 The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric Gregory John Saldaña University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Saldaña, Gregory John, "The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric" (2000). Theses (Historic Preservation). 423. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/423 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Saldaña, Gregory John (2000). The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/423 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Saldaña, Gregory John (2000). The Introduction of a Contemporary Building into a Historic Fabric. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/423 piPK^I!^!^^ ;^-"v \^««> r.A <^'{5^ -;>• i' W 'if UNIVERSITY^ PENNSYLVANIA. UBRARIE5 THE INTRODUCTION OF A CONTEMPORARY BUILDING INTO A HISTORIC FABRIC Gregory John Saldana A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2000 N^1_.^>,LjL->--v->^ isor eadCT David De Long FhsikiS. -

Indian Trade Cloth in Egypt: the Newberry Collection

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1990 Indian Trade Cloth in Egypt: The Newberry Collection Ruth Barnes Ashmolean Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Barnes, Ruth, "Indian Trade Cloth in Egypt: The Newberry Collection" (1990). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 594. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/594 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -179- Indian Trade Cloth in Egypt: holdings are vast by comparison: there is a total of 1225 The Newberry Collection block-printed fragments. The size is matched by quality and variation of design; virtually any pattern known in this kind RUTH BARNES of textile is well represented, and there are pieces which are Ashiaolean Museum probably unique.3 However, the collection is not widely known, Oxford and until very recently (May 1990) it could not be used as research material, as the fragments had not been properly The Department of Eastern Art in the Ashmolean Museum, accessioned into the Department's holdings, hence had no Oxford, holds what is undoubtably one of the largest single number or" other means -of identification which made them collections of block-printed textiles produced in India, but available as a reference. -

Trip to Egypt January 25 to February 8, 2020. Day 1

Address : Group72,building11,ap32, El Rehab city. Cairo ,Egypt. tel : 002 02 26929768 cell phone: 002 012 23 16 84 49 012 20 05 34 44 Website : www.mirusvoyages.com EMAIL:[email protected] Trip to Egypt January 25 to February 8, 2020. Day 1 Travel from Chicago to Cairo Day 2 Arrival at Cairo airport, meet & assistance, transfer to the hotel. Overnight at the hotel in Cairo. Day 3 Saqqara, the oldest complete stone building complex known in history, Saqqara features numerous pyramids, including the world-famous Step pyramid of Djoser, Visit the wonderful funerary complex of the King Zoser & Mastaba (Arabic word meaning 'bench') of a Noble. Lunch in a local restaurant. Visit the three Pyramids of Giza, the pyramid of Cheops is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the only one to remain largely intact. ), the Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world for more than 3,800 years. The temple of the valley & the Sphinx. Overnight at the hotel in Cairo. Day 4 Visit the Mokattam church, also known by Cave Church & garbage collectors( Zabbaleen) Mokattam, it is the largest church in the Middle East, seating capacity of 20,000. Visit the Coptic Cairo, Visit The Church of St. Sergius (Abu Sarga) is the oldest church in Egypt dating back to the 5th century A.D. The church owes its fame to having been constructed upon the crypt of the Holy Family where they stayed for three months, visit the Hanging Church (The Address : Group72,building11,ap32, El Rehab city. -

CAIRO T E N a L 109 P Y L E N Park O L

© Lonely Planet 109 Cairo CAIRO Let’s address the drawbacks first. The crowds on a Cairo footpath make Manhattan look like a ghost town. You will be hounded by papyrus sellers at every turn. Your life will flash before your eyes each time you venture across a street. And your snot will run black from the smog. But it’s a small price to pay to visit the city Cairenes call Umm ad-Dunya – the Mother of the World. This city has an energy, palpable even at three in the morning, like no other. It’s the product of its 20 million inhabitants waging a battle against the desert and winning (mostly), of 20 million people simultaneously crushing the city’s infrastructure under their collective weight and lifting the city’s spirit up with their uncommon graciousness and humour. One taxi ride can span millennia, from the resplendent mosques and mausoleums built at the pinnacle of the Islamic empire, to the 19th-century palaces and grand avenues (which earned the city the nickname ‘Paris on the Nile’), to the brutal concrete blocks of the Nasser years – then all the way back to the days of the pharaohs, as the Pyramids of Giza hulk on the western edge of the city. The architectural jumble is smoothed over by an even coating of beige sand, and the sand is a social equaliser as well: everyone, no matter how rich, gets dusty when the spring khamsin blows in. So blow your nose, crack a joke and learn to look through the dirt to see the city’s true colours.