Breaking up Britain.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

Living Entanglements and the Ecological Thought in the Works Of

LIVING ENTANGLEMENTS AND THE ECOLOGICAL THOUGHT IN THE WORKS OF PAUL KINGSNORTH, TOM MCCARTHY, AND ALI SMITH By Garrett Joseph Peace James J. Arnett Andrew D. McCarthy Associate Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Heather M. Palmer Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) LIVING ENTANGLEMENTS AND THE ECOLOGICAL THOUGHT IN THE WORKS OF PAUL KINGSNORTH, TOM MCCARTHY, AND ALI SMITH By Garrett Joseph Peace A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts: English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee May 2021 ii ABSTRACT In my thesis, I use the work of Donna Haraway, Timothy Morton, Karen Barad, and Anna Tsing to explore how three contemporary British novelists—Paul Kingsnorth, Tom McCarthy, and Ali Smith—deal with the representational and ethical challenges of writing about nature and climate change within the Anthropocene. The question of how to live and write now is a prominent thread in all their works, which show, in both form and content, the entanglements of ecology, materiality, locality, nationality, and personal identity. In doing so, their stories enable readers to engage with what Morton calls the “ecological thought,” i.e. “a practice and process of becoming fully aware of how human beings are connected with other beings,” and provoke us, as Haraway puts it, “to be truly present . as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.” iii DEDICATION For my parents, Robin and James. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As many of the writers present in these pages show us, to be human is to exist in a state of interconnection. -

LANGUAGE VARIETY in ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England

LANGUAGE VARIETY IN ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England One thing that is important to very many English people is where they are from. For many of us, whatever happens to us in later life, and however much we move house or travel, the place where we grew up and spent our childhood and adolescence retains a special significance. Of course, this is not true of all of us. More often than in previous generations, families may move around the country, and there are increasing numbers of people who have had a nomadic childhood and are not really ‘from’ anywhere. But for a majority of English people, pride and interest in the area where they grew up is still a reality. The country is full of football supporters whose main concern is for the club of their childhood, even though they may now live hundreds of miles away. Local newspapers criss-cross the country in their thousands on their way to ‘exiles’ who have left their local areas. And at Christmas time the roads and railways are full of people returning to their native heath for the holiday period. Where we are from is thus an important part of our personal identity, and for many of us an important component of this local identity is the way we speak – our accent and dialect. Nearly all of us have regional features in the way we speak English, and are happy that this should be so, although of course there are upper-class people who have regionless accents, as well as people who for some reason wish to conceal their regional origins. -

The Story of New Jersey

THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY HAGAMAN THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Examination Copy THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY (1948) A NEW HISTORY OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY is for use in the intermediate grades. A thorough story of the Middle Atlantic States is presented; the context is enriohed with illustrations and maps. THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY begins with early Indian Life and continues to present day with glimpses of future growth. Every aspect from mineral resources to vac-| tioning areas are discussed. 160 pages. Vooabulary for 4-5 Grades. List priceJ $1.28 Net price* $ .96 (Single Copy) (5 or more, f.o.b. i ^y., point of shipment) i^c' *"*. ' THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Linooln, Nebraska ..T" 3 6047 09044948 8 lererse The Story of New Jersey BY ADALINE P. HAGAMAN Illustrated by MARY ROYT and GEORGE BUCTEL The University Publishing Company LINCOLN NEW YORK DALLAS KANSAS CITY RINGWOOD PUBLIC LIBRARY 145 Skylands Road Ringwood, New Jersey 07456 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW.JERSEY IN THE EARLY DAYS Before White Men Came ... 5 Indian Furniture and Utensils 19 Indian Tribes in New Jersey 7 Indian Food 20 What the Indians Looked Like 11 Indian Money 24 Indian Clothing 13 What an Indian Boy Did... 26 Indian Homes 16 What Indian Girls Could Do 32 THE WHITE MAN COMES TO NEW JERSEY The Voyage of Henry Hudson 35 The English Take New Dutch Trading Posts 37 Amsterdam 44 The Colony of New The English Settle in New Amsterdam 39 Jersey 47 The Swedes Come to New New Jersey Has New Jersey 42 Owners 50 PIONEER DAYS IN NEW JERSEY Making a New Home 52 Clothing of the Pioneers .. -

Disunited Kingdom?

DISUNITED KINGDOM? ATTITUDES TO THE EU ACROSS THE UK Rachel Ormston Head of Social Attitudes at NatCen Social Research Disunited kingdom? Attitudes to the EU across the UK This paper examines the nature and scale of differences in support for the European Union across the four constituent countries of the UK. It assesses how far apart opinion in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland appears to be. It reviews the current state of the polls in each country and what this suggests about whose views might determine the outcome of the referendum. Finally, it examines potential reasons for the variation between England, Scotland and Wales in the level of support for EU membership, including differences in demographic profile, party structure and national identity. FAR FROM UNITED ON EUROPE Although recent poll and survey data suggests a slight majority favour remaining in the EU, the size of this majority is much narrower in England than in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. 52% 55% 64% 75% Figures based on mean of recent polls 2 DISUNITED KINGDOM? ATTITUDES TO THE EU ACROSS THE UK PARTY POLITICS AND PUBLIC OPINION England’s relatively anti-EU mood reflects the relatively high level of support for (anti-EU) UKIP and (partly Eurosceptic) Conservatives. LEAVE REMAIN UKIP SNP LABOUR LIBERAL PLAID CYMRU CONSERVATIVE DEMOCRATS AN ENGLISH REFERENDUM? Within England, people who feel particularly strongly English are the most likely to want Britain to leave the EU. LEAVE! DISUNITED KINGDOM? ATTITUDES TO THE EU ACROSS THE UK 3 INTRODUCTION From the perspective of 2015, constant constitutional wrangling seems to have become the norm in the UK. -

A Guide to English Culture and Customs

A GUIDE TO ENGLISH CULTURE AND CUSTOMS This document has been prepared for you to read before you leave for England, and to refer to during your time there. It gives you information about English customs and describes some points that may be different from your own culture. Part of the fun of coming to live or study in another country is observing and learning about the culture and customs of its people. We don’t want to spoil the surprise for you but we do understand that it can be useful to know how other people will expect you to behave, and will behave towards you whilst you’re away from home. This can avoid awkward misunderstandings for both you and the people you meet and make friends with! We hope that your stay in England will be thoroughly enjoyable and we very much look forward to welcoming you at St Giles College. Queues – The English are famous for being very polite. Always join the back of the queue and wait your turn when buying tickets, waiting in a bank, post office or for a bus or train. If you ‘jump the queue’ in England you are known as a ‘queue jumper’ and although people may not say anything to you, they will make very unhappy noises! If there is any confusion about whether there is one queue or more for several different cashiers, you should still wait your turn and stay behind everyone who arrived before you. English people do not try to get to the front first; they are very fair. -

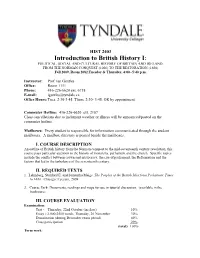

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

The History of England A. F. Pollard

The History of England A study in political evolution A. F. Pollard, M.A., Litt.D. CONTENTS Chapter. I. The Foundations of England, 55 B.C.–A.D. 1066 II. The Submergence of England, 1066–1272 III. Emergence of the English People, 1272–1485 IV. The Progress of Nationalism, 1485–1603 V. The Struggle for Self-government, 1603–1815 VI. The Expansion of England, 1603–1815 VII. The Industrial Revolution VIII. A Century of Empire, 1815–1911 IX. English Democracy Chronological Table Bibliography Chapter I The Foundations of England 55 B.C.–A.D. 1066 "Ah, well," an American visitor is said to have soliloquized on the site of the battle of Hastings, "it is but a little island, and it has often been conquered." We have in these few pages to trace the evolution of a great empire, which has often conquered others, out of the little island which was often conquered itself. The mere incidents of this growth, which satisfied the childlike curiosity of earlier generations, hardly appeal to a public which is learning to look upon historical narrative not as a simple story, but as an interpretation of human development, and upon historical fact as the complex resultant of character and conditions; and introspective readers will look less for a list of facts and dates marking the milestones on this national march than for suggestions to explain the formation of the army, the spirit of its leaders and its men, the progress made, and the obstacles overcome. No solution of the problems presented by history will be complete until the knowledge of man is perfect; but we cannot approach the threshold of understanding without realizing that our national achievement has been the outcome of singular powers of assimilation, of adaptation to changing circumstances, and of elasticity of system. -

Understanding Wales: Nationalism and Culture

Colonial Academic Alliance Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 4 Article 7 2015 Understanding Wales: Nationalism and Culture Yen Nguyen University of North Carolina - Wilmington, [email protected] Robin Reeves University of North Carolina - Wilmington, [email protected] Cassius M. Hossfeld University of North Carolina - Wilmington, [email protected] Angelique Karditzas University of North Carolina - Wilmington, [email protected] Bethany Williams University of North Carolina - Wilmington, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/caaurj Recommended Citation Nguyen, Yen; Reeves, Robin; Hossfeld, Cassius M.; Karditzas, Angelique; Williams, Bethany; Hayes, Brittany; Price, Chelsea; Sherwood, Kate; Smith, Catherine; and Simons, Roxy (2015) "Understanding Wales: Nationalism and Culture," Colonial Academic Alliance Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/caaurj/vol4/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colonial Academic Alliance Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Understanding Wales: Nationalism and Culture Cover Page Note Acknowledgements The authors thank Dr. Leslie Hossfeld of the Department of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington for the valuable comments and guidance given with much patience -

The Prize for the New Novelist of the Year #Discoveradebut Desmondelliottprize.Org

The Prize for the New Novelist of the Year #DiscoverADebut DesmondElliottPrize.org “The most prestigious award for first-time novelists” - Daily Telegraph About the Prize About Desmond Elliott The Desmond Elliott Prize was founded to celebrate the best first novel by a new author and In life, Desmond Elliott incurred the wrath of Dame Edith Sitwell and the love of innumerable authors and colleagues to support writers just starting what will be long and glittering careers. It has succeeded who regarded him as simply “the best”. Jilly Cooper, Sam in its mission in a manner that would make Elliott proud. Llewelyn, Penny Vincenzi, Leslie Thomas and Candida Lycett Green are among the writers forever in his debt. So, too, Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber: if Elliott In the years since its inception, it has managed to stand Every winner since the first in 2008 has gone on to be had not introduced the aspirant lyricist and composer, the out from other prizes due to the quality of its selections, the shortlisted for, and in many cases win, other high-profile West End—and Broadway—would have been the poorer. prestige of its judges and its unusually focused shortlist— literary awards, among them the Baileys Women’s Prize only three titles make it to that stage. With judges of the for Fiction, the Man Booker Prize and the Costa First In death, Desmond Elliott continues to launch careers for calibre of Geordie Grieg, Edward Stourton, Joanne Harris, Novel Award. In less than a decade, the words ‘Winner he stipulated that the proceeds of his estate be invested in a Chris Cleave, Elizabeth Buchan and Viv Groskop, to of the Desmond Elliott Prize’ have become synonymous charitable trust that would fund a literary award “to enrich name just a few, fantastic winners have been chosen year with original, compelling writing by the most exciting the careers of new writers”, launching them on a path on after year. -

Changing Englishness: in Search of National Identity*

ISSN 1392-0561. INFORMACIJOS MOKSLAI. 2008 45 Changing Englishness: In search of national identity* Elke Schuch Cologne University of Applied Sciences Institute of Translation and Multilingual Communication Mainzer Str. 5, D-50678 Köln, Germany Ph. +49-221/8275-3302 E-mail: [email protected] The subsumation of Englishness into Britishness to the extent that they were often indistinguishable has contributed to the fact that at present an English identity is struggling to emerge as a distinct category. While devolved Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have been able to construct a strong sense of local identity for themselves in opposition to the dominant English, England, without an e�uivalent Other, has never had to explain herself in the way Scotland or Wales have had to. But now, faced with the af- ter-effects of globalisation, devolution and an increasingly cosmopolitan and multicultural society as a conse�uence of de-colonisation and migration, the English find it difficult to invent a postimperial identity for themselves. This paper argues that there are chances and possibilities to be derived from the alleged crisis of Englishness: Britain as a nation-state has always accommodated large numbers of non-English at all levels of society. If England manages to re-invent itself along the lines of a civic, non- ethnic Britishness with which it has been identified for so long, the crisis might turn into the beginning of a more inclusive and cosmopolitan society which acknowledges not just the diversification of the people, particularly the legacy of the Empire, but also realises that the diversity of cultures has to be accommo- dated within a common culture. -

YOUNG PEOPLE and BRITISH IDENTITY Gayatri Ganesh, Senior Research Executive, Ipsos MORI 79-81 Borough Road London SE1 1FY

YOUNG AND BRITISHY PEOPLEIDENTIT Research Study Conducted for The Camelot Foundation by Ipsos MORI Contact Details This research was carried out by the Ipsos MORI Qualitative HotHouse: Annabelle Phillips, Research Director, Ipsos MORI YOUNG PEOPLE AND BRITISH IDENTITY Gayatri Ganesh, Senior Research Executive, Ipsos MORI 79-81 Borough Road London SE1 1FY. Tel: 020 7347 3000 Fax: 020 7347 3800 Email: fi [email protected] Internet: www.ipsos-mori.com ©Ipsos MORI/Camelot Foundation J28609 CCheckedhecked & AApproved:pproved: MModels:odels: Annabelle Phillips Pedro Moro Gayatri Ganesh Brandon Palmer Sarah Castell Triston Davis Rachel Sweetman Fiona Bond Joe Lancaster Laura Grievson Samantha Hyde Nosheen Akhtar Helen Bryant Zabeen Akhtar Emma Lynass PPhotographyhotography & DDesign:esign: Diane Hutchison Jay Poyser Dan Rose Julia Burstein CONTENTS Forward.....1 Acknowledgements.....2 Background and Objectives 3 Methodology.....4 Qualitative phase.....4 The group composition.....5 Quantitative phase.....6 Interpretation of qualitative research.....6 Semiotics.....7 Interpretation of semiotics.....9 Report structure.....10 Publication of data.....10 Executive summary 11 Young people’s lives today.....13 The challenge of Britishness.....14 Where next for British youth identity?.....16 Young people in Britain today 19 Young people’s lives today.....21 My identity.....21 My local area.....23 Young people’s views on living in Britain.....28 Where is the concept of Britain relevant.....30 National and ethnic identities 37 England.....39