Living Entanglements and the Ecological Thought in the Works Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22Nd NFF Announces Screenwriters Tribute

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NANTUCKET FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES TOM MCCARTHY TO RECEIVE 2017 SCREENWRITERS TRIBUTE AWARD NICK BROOMFIELD TO BE RECOGNIZED WITH SPECIAL ACHIEVEMENT IN DOCUMENTARY STORYTELLING NFF WILL ALSO HONOR LEGENDARY TV CREATORS/WRITERS DAVID CRANE AND JEFFREY KLARIK WITH THE CREATIVE IMPACT IN TELEVISION WRITING AWARD New York, NY (April 6, 2017) – The Nantucket Film Festival announced today the honorees who will be celebrated at this year’s Screenwriters Tribute—including Oscar®-winning writer/director Tom McCarthy, legendary documentary filmmaker Nick Broomfield, and ground-breaking television creators and Emmy-nominated writing team David Crane and Jeffrey Klarik. The 22nd Nantucket Film Festival (NFF) will take place June 21-26, 2017, and celebrates the art of screenwriting and storytelling in cinema and television. The 2017 Screenwriters Tribute Award will be presented to screenwriter/director Tom McCarthy. McCarthy's most recent film Spotlight was awarded the Oscar for Best Picture and won him (and his co-writer Josh Singer) an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. McCarthy began his career as a working actor until he burst onto the filmmaking scene with his critically acclaimed first feature The Station Agent, starring Peter Dinklage, Patricia Clarkson, Bobby Cannavale, and Michelle Williams. McCarthy followed this with the equally acclaimed film The Visitor, for which he won the Spirit Award for Best Director. He also shared story credit with Pete Docter and Bob Peterson on the award-winning animated feature Up. Previous recipients of the Screenwriters Tribute Award include Oliver Stone, David O. Russell, Judd Apatow, Paul Haggis, Aaron Sorkin, Nancy Meyers and Steve Martin, among others. -

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23Rd, 2019

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23rd, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 24th ANNUAL NANTUCKET FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES FEATURE FILM LINEUP DANNY BOYLE’S YESTERDAY TO OPEN FESTIVAL ALEX HOLMES’ MAIDEN TO CLOSE FESTIVAL LULU WANG’S THE FAREWELL TO SCREEN AS CENTERPIECE DISNEY•PIXAR’S TOY STORY 4 PRESENTED AS OPENING FAMILY FILM IMAGES AVAILABLE HERE New York, NY (April 23, 2019) – The Nantucket Film Festival (NFF) proudly announced its feature film lineup today. The opening night selection for its 2019 festival is Universal Pictures’ YESTERDAY, a Working Title production written by Oscar nominee Richard Curtis (Four Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually, and Notting Hill) from a story by Jack Barth and Richard Curtis, and directed by Academy Award® winner Danny Boyle (Slumdog Millionaire, Trainspotting, 28 Days Later). The film tells the story of Jack Malik (Himesh Patel), a struggling singer-songwriter in a tiny English seaside town who wakes up after a freak accident to discover that The Beatles have never existed, and only he remembers their songs. Sony Pictures Classics’ MAIDEN, directed by Alex Holmes, will close the festival. This immersive documentary recounts the thrilling story of Tracy Edwards, a 24-year-old charter boat cook who became the skipper of the first ever all-female crew to enter the Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race. The 24th Nantucket Film Festival runs June 19-24, 2019, and celebrates the art of screenwriting and storytelling in cinema. A24’s THE FAREWELL, written and directed by Lulu Wang, will screen as the festival’s Centerpiece film. -

Hergé and Tintin

Hergé and Tintin PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 20 Jan 2012 15:32:26 UTC Contents Articles Hergé 1 Hergé 1 The Adventures of Tintin 11 The Adventures of Tintin 11 Tintin in the Land of the Soviets 30 Tintin in the Congo 37 Tintin in America 44 Cigars of the Pharaoh 47 The Blue Lotus 53 The Broken Ear 58 The Black Island 63 King Ottokar's Sceptre 68 The Crab with the Golden Claws 73 The Shooting Star 76 The Secret of the Unicorn 80 Red Rackham's Treasure 85 The Seven Crystal Balls 90 Prisoners of the Sun 94 Land of Black Gold 97 Destination Moon 102 Explorers on the Moon 105 The Calculus Affair 110 The Red Sea Sharks 114 Tintin in Tibet 118 The Castafiore Emerald 124 Flight 714 126 Tintin and the Picaros 129 Tintin and Alph-Art 132 Publications of Tintin 137 Le Petit Vingtième 137 Le Soir 140 Tintin magazine 141 Casterman 146 Methuen Publishing 147 Tintin characters 150 List of characters 150 Captain Haddock 170 Professor Calculus 173 Thomson and Thompson 177 Rastapopoulos 180 Bianca Castafiore 182 Chang Chong-Chen 184 Nestor 187 Locations in Tintin 188 Settings in The Adventures of Tintin 188 Borduria 192 Bordurian 194 Marlinspike Hall 196 San Theodoros 198 Syldavia 202 Syldavian 207 Tintin in other media 212 Tintin books, films, and media 212 Tintin on postage stamps 216 Tintin coins 217 Books featuring Tintin 218 Tintin's Travel Diaries 218 Tintin television series 219 Hergé's Adventures of Tintin 219 The Adventures of Tintin 222 Tintin films -

The Goldsmiths Prize and Its Conceptualization of Experimental Literature

The Goldsmiths Prize and Its Conceptualization 35 of Experimental Literature The Goldsmiths Prize and Its Conceptualization of Experimental Literature Wojciech Drąg University of Wrocław Abstract: In the aftermath of a critical debate regarding the Man Booker Prize’s adoption of ‘readability’ as the main criterion of literary value, Goldsmiths College established a new literary prize. The Goldsmiths Prize was launched in 2013 as a celebration of ‘fiction that breaks the mould or extends the possibil- ities of the novel form.’ Throughout its six editions, the prize has been awarded to such writers as Ali Smith, Nicola Barker and Eimear McBride, and has at- tracted a lot of media attention. Annually, its jury have written press features praising the shortlisted books, while invited novelists have given lectures on the condition of the novel. Thanks to its quickly won popularity, the Goldsmiths Prize has become the main institution promoting – and conceptualizing – ‘ex- perimental’ fiction in Britain. This article aims to examine all the promotional material accompanying each edition – including jury statements, press releases and commissioned articles in the New Statesman – in order to analyze how the prize defines experimentalism. Keywords: Goldsmiths Prize, literary prizes, experimental literature, avant-gar- de, contemporary British fiction Literary experimentalism is a notion both notoriously difficult to define and generally disliked by those to whose work it is often applied. B.S. Johnson famously stated that ‘to most reviewers [it] is almost always a synonym for “unsuccessful”’ (1973, 19). Among other acclaimed avant-garde authors who defied the label were Raymond Federmann and Ronald Sukenick (Bray, Gib- bon, and McHale 2012, 2-3). -

Tintin and the Adventure of Transformative and Critical Fandom

. Volume 17, Issue 2 November 2020 Tintin and the adventure of transformative and critical fandom Tem Frank Andersen & Thessa Jensen, Aalborg University, Denmark Abstract: Using Roland Barthes’ and John Fiske’s notion of the readerly, writerly, and producerly text, this article provides an analysis and a tentative categorization of chosen transformative, fanmade texts for the comic book series The Adventures of Tintin. The focus is on the critical transformation of, and engagement with, the original text by academics, professional fans, and fans of popular culture. The analysis identifies different ways of transformational engagement with the original text: ranging from the academic writerly approach of researchers, over professional fans rewriting and critically engaging with the original text, to fanfiction fans reproducing heteroromantic tropes in homoerotic stories, fans of popular culture using Tintin figurines to document their own travels, and finally, fans who use Tintin covers as a way to express critical political sentiments. With Barthes and Fiske these groups are defined by their way of approaching the original text, thus working either in a readerly producerly or writerly producerly way, depending on how critical and political the producerly attitude is in regard to the original text. Keywords: The Adventures of Tintin, fan albums, fanfiction, fan communities; readerly, writerly, producerly reception Introduction In recent years, it has been quiet around the forever young reporter Tintin and his faithful friends Snowy and Captain Haddock. A motion capture movie about three of Tintin’s adventures failed to garner a larger following, despite having Steven Spielberg as the director (The Adventures of Tintin, Columbia Pictures, 2011). -

2020 Spring Adult Rights Guide

Incorporating Gregory & company Highlights London Book Fair 2020 Highlights Welcome to our 2020 International Book Rights Highlights For more information please go to our website to browse our shelves and find out more about what we do and who we represent. Contents Fiction Literary Fiction 4 to 11 Upmarket Fiction 12 to 17 Commercial Fiction 18 to 19 Crime and Thriller 20 to 31 Non-Fiction Politics, Current Affairs, International Relations 32 to 39 History and Philosophy 40 to 43 Nature and Science 44 to 47 Biography and Memoir 48 to 54 Practical, How-To and Self-Care 55 to 57 Upcoming Publications 58 to 59 Recent Highlights 60 Prizes 61 Film and TV News 62 to 64 DHA Co-Agents 65 Primary Agents US Rights: Veronique Baxter; Jemima Forrester; Georgia Glover; Anthony Goff (AG); Andrew Gordon (AMG); Jane Gregory; Lizzy Kremer; Harriet Moore; Caroline Walsh; Laura West; Jessica Woollard Film & TV Rights: Clare Israel; Penelope Killick; Nicky Lund; Georgina Ruffhead Translation Rights Alice Howe: [email protected] Direct: France; Germany Margaux Vialleron: [email protected] Direct: Denmark; Finland; Iceland; Italy, the Netherlands; Norway; Sweden Emma Jamison: [email protected] Direct: Brazil; Portugal; Spain and Latin America Co-agented: Poland Lucy Talbot: [email protected] Direct: Croatia; Estonia; Latvia; Lithuania; Slovenia Co-agented: China; Hungary, Japan; Korea; Russia; Taiwan; Turkey; Ukraine Imogen Bovill: [email protected] Direct: Arabic; Albania; Bulgaria; Greece; Israel; Italy; Macedonia, Vietnam, all other markets. Co-agented: Czech Republic; Indonesia; Romania; Serbia; Slovakia; Thailand Contact t: +44 (0)20 7434 5900 f: +44 (0)20 7437 1072 www.davidhigham.co.uk General translation rights enquiries: Sam Norman: [email protected] THE PALE WITNESS Patricia Duncker A tour de force of historical fiction from the acclaimed novelist Patricia Duncker According to the Gospel of Matthew, the wife of Pontius Pilate interceded on Jesus’ behalf as Pilate was contemplating the prophet’s fate. -

The Prize for the New Novelist of the Year #Discoveradebut Desmondelliottprize.Org

The Prize for the New Novelist of the Year #DiscoverADebut DesmondElliottPrize.org “The most prestigious award for first-time novelists” - Daily Telegraph About the Prize About Desmond Elliott The Desmond Elliott Prize was founded to celebrate the best first novel by a new author and In life, Desmond Elliott incurred the wrath of Dame Edith Sitwell and the love of innumerable authors and colleagues to support writers just starting what will be long and glittering careers. It has succeeded who regarded him as simply “the best”. Jilly Cooper, Sam in its mission in a manner that would make Elliott proud. Llewelyn, Penny Vincenzi, Leslie Thomas and Candida Lycett Green are among the writers forever in his debt. So, too, Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber: if Elliott In the years since its inception, it has managed to stand Every winner since the first in 2008 has gone on to be had not introduced the aspirant lyricist and composer, the out from other prizes due to the quality of its selections, the shortlisted for, and in many cases win, other high-profile West End—and Broadway—would have been the poorer. prestige of its judges and its unusually focused shortlist— literary awards, among them the Baileys Women’s Prize only three titles make it to that stage. With judges of the for Fiction, the Man Booker Prize and the Costa First In death, Desmond Elliott continues to launch careers for calibre of Geordie Grieg, Edward Stourton, Joanne Harris, Novel Award. In less than a decade, the words ‘Winner he stipulated that the proceeds of his estate be invested in a Chris Cleave, Elizabeth Buchan and Viv Groskop, to of the Desmond Elliott Prize’ have become synonymous charitable trust that would fund a literary award “to enrich name just a few, fantastic winners have been chosen year with original, compelling writing by the most exciting the careers of new writers”, launching them on a path on after year. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Gordon Burn Prize 2018: 13-Strong Longlist Highlights Fearless Works of Fiction and Non-Fiction

Gordon Burn Prize 2018: 13-strong longlist highlights fearless works of fiction and non-fiction News release for release 00:00 18 May 2018 The longlist is announced today for the Gordon Burn Prize 2018, which seeks to reward some of the boldest and most fearless new books published in the United Kingdom and the United States. Denise Mina won the prize in 2017 for her true crime novel The Long Drop. Previous winners have included David Szalay’s linked collection of short stories, All That Man Is, and In Plain Sight: The Life and Lies of Jimmy Savile by Dan Davies. Gordon Burn’s writing was precise and rigorous, and often blurred the line Between fact and fiction. He wrote across a wide range of suBjects, from celeBrities to serial killers, politics to contemporary art; his works include the novels Fullalove and Born Yesterday: The News as a Novel and non-fiction Happy Like Murderers: The Story of Fred and Rosemary West, Best and Edwards: Football, Fame and Oblivion and Sex & Violence, Death & Silence: Encounters with Recent Art. The Gordon Burn Prize, founded in 2012 and run in partnership By the Gordon Burn Trust, New Writing North, FaBer & FaBer and Durham Book Festival, seeks to celebrate the work of those who follow in his footsteps: novels that dare to enter history and interrogate the past; non-fiction adventurous enough to inhaBit characters and events to create new and vivid realities. The prize is open to works in English published between 1 July 2017 and 1 July 2018, by writers of any nationality or descent who are resident in the United Kingdom or the United States of America. -

ANNUAL REPORT for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2019

ST. RITA OF CASCIA HIGH SCHOOL ANNUAL REPORT for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2019 TRUTH UNITY LOVE Veritas Unitas Caritas ADMINISTRATION President TRUTH UNITY LOVE James Quaid, Ph.D. VeritasUnitas Caritas Chairman of the Board Ernest J. Mrozek, ‘71 Vice President of Academics Wes Benak, ‘81 Vice President of Student Life CONTENT Josh Blaszak ‘02 Vice President of Finance SCHOOL NEWS Eileen Spulak OFFICE OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT page 1 | A Message from Jim Quaid Director of Institutional Advancement page 2 | Fall Sports Wrap Up Jim Juchcinski ‘97 Director of Annual Appeal and Major Gifts page 4 | The Caritas Project John Schmitt ‘84 Associate Director of Advancement & page 6 | St. Rita Welcomes New President Director of Advancement Communications Laura Fleck page 8 | Students Explore Career Opportunities Database Manager & Director of Special Events Mary Gal Carroll Beyond the Classroom Director of Alumni & Donor Relations page 10 | Faculty Spotlight: Robyn Kurnat Rob Gallik ‘10 BOARD OF DIRECTORS ALUMNI/ADVANCEMENT NEWS Ernest Mrozek ‘71 (Chairman) Victoria Barrios page 12 | Career Day James Brasher ‘71 Bernard DelGiorno HON Lawrence Doyle ‘68 page 14 | Mustangs in the MLB James Gagnard ‘64 Thomas Healy ‘83 page 15 | A Message from Jim Juchcinski ‘97 Catharine Hennessy David Howicz ‘84 Nicholas LoMaglio ‘04 page 16 | Keeping Track Donald Mrozek ‘65 Clare Napleton page 17 | 1905 Guild Charles Nash ‘71 John O’Neill ‘79 page 18 | Summary Financial Statement Fr. Anthony Pizzo, O.S.A. Timothy Ray ‘87 Br. Joe Ruiz, O.S.A. page 19 | Honor Roll of Donors Stephen Schaller ‘83 Fr. Bernard Scianna, O.S.A. -

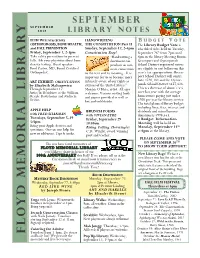

F L O Y D M E M O R Ia L L Ib R

SEPTEMBER s E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 7 Library NOTES ELIH WELLNESS SERIES HANDWRITING B UDGET V OTE OSTEOPOROSIS, BONE HEALTH, THE CONSTITUTION Part II The Library Budget Vote is and FALL PREVENTION Sunday, September 17, 2-4pm scheduled to be held on Tuesday, Friday, September 1, 2-3pm Constitution Day! September 26th from 2pm until Take safety precautions to prevent “Handwriting a 8pm in the library Meeting Room. falls. Ask your physician about bone document can Greenport and Oysterponds density testing. Guest speaker: produce an inti- School District registered voters Fred Carter, MD, Board Certified mate connection are eligible to cast ballots on this Orthopedist. year’s tax appropriation. Green- to the text and its meaning...It is important for us to become more port School District will contri- ART EXHIBIT: ORIENTATION intensely aware of our rights as bute $520,184 and the Oyster- by Elizabeth Malunowicz citizens of the United States.” ponds School District $457,628. l i bThrough r a ry September 17 Morgan O’Hara, artist. All ages This is a decrease of about 7.5% Artist-in-Residence at the William over last year with the average welcome. Various writing tools Steeple Davis home and studio in and papers provided as well as homeowner paying just under Orient. hot and cold drinks. $200 per year for library service. The total planned library budget including fines, fees, interest and APPLE HELP BRUNCH POEMS dividends and miscellaneous with FRED SHARMAN with VIVIAN EYRE donations is $998,653. Tuesdays, September 5–19 Friday, September 29 A Budget Information 3-5pm 10:30am Meeting will be held on Bring your Apple devices and Rising, Falling, Hovering by Monday, September 11th questions. -

Highlights Frankfurt Book Fair 2018 Highlights

Highlights Frankfurt Book Fair 2018 Highlights Welcome to our 2018 International Book Rights Highlights For more information please go to our website to browse our shelves and find out more about what we do and who we represent. Contents Fiction Literary/Upmarket Fiction 1 - 10 Crime, Suspense, Thriller 11 - 24 Historical Fiction 25 - 26 Women’s Fiction 27 - 32 Non-Fiction Philosophy 33 - 36 Memoir 37 - 38 History 39 - 44 Science and Nature 45 - 47 Upcoming Publications 48 - 49 Reissues 50 Prize News 51 Film & TV news 52 Sub-agents 53 Primary Agents US Rights: Veronique Baxter; Jemima Forrester; Georgia Glover; Anthony Goff (AG); Andrew Gordon (AMG); Jane Gregory; Lizzy Kremer; Harriet Moore; Caroline Walsh Film & TV Rights: Clare Israel; Nicky Lund; Penelope Killick; Georgina Ruffhead Translation Rights Alice Howe: [email protected] Direct: France; Germany Claire Morris: [email protected] Direct: Denmark; Finland; Iceland; Italy; the Netherlands; Norway; Sweden Emma Jamison: [email protected] Direct: Brazil; Portugal; Spain and Latin America Sub-agented: Poland Emily Randle: [email protected] Direct: Croatia; Estonia; Latvia; Lithuania; Slovenia Subagented: China; Hungary, Japan; Korea; Russia; Taiwan; Turkey; Ukraine Margaux Vialleron: [email protected] Direct: Arabic; Albania; Greece; Israel; Macedonia, Vietnam plus miscellaneous requests. Audio in France and Germany Sub-agented: Bulgaria; Czech Republic; Indonesia; Romania; Serbia; Slovakia; Thailand Contact t: +44 (0)20 7434 5900 f: +44 (0)20 7437 1072 www.davidhigham.co.uk The Black Prince Anthony Burgess & Adam Roberts A novel by Adam Roberts, adapted from an original script by Anthony Burgess ‘I’m working on a novel intended to express the feel of England in Edward II’s time ..