1 Philosophical Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance U.S

1 Check website or mobile app for full description and content information. description app for full Check website or mobile #sundance • sundance.org/festival sundance.org/festival Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance The U.S. Dramatic Competition Films As You Are The Birth of a Nation U.S. Dramatic Competition Dramatic U.S. Many of these films have not yet been rated by the Motion Picture Association of America. Read the full descriptions online and choose responsibly. Films are generally followed by a Q&A with the director and selected members of the cast and crew. All films are shown in 35mm, DCP, or HDCAM. Special thanks to Dolby Laboratories, Inc., for its support of our U.S.A., 2016, 110 min., color U.S.A., 2016, 117 min., color digital cinema projection. As You Are is a telling and retelling of a Set against the antebellum South, this story relationship between three teenagers as it follows Nat Turner, a literate slave and traces the course of their friendship through preacher whose financially strained owner, PROGRAMMERS a construction of disparate memories Samuel Turner, accepts an offer to use prompted by a police investigation. Nat’s preaching to subdue unruly slaves. Director, Associate Programmers Sundance Film Festival Lauren Cioffi, Adam Montgomery, After witnessing countless atrocities against 2 John Cooper Harry Vaughn fellow slaves, Nat devises a plan to lead his DIRECTOR: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte people to freedom. Director of Programming Shorts Programmers SCREENWRITERS: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, Trevor Groth Dilcia Barrera, Emily Doe, Madison Harrison Ernesto Foronda, Jon Korn, PRINCIPAL CAST: Owen Campbell, DIRECTOR/SCREENWRITER: Nate Parker Senior Programmers Katie Metcalfe, Lisa Ogdie, Charlie Heaton, Amandla Stenberg, PRINCIPAL CAST: Nate Parker, David Courier, Shari Frilot, Adam Piron, Mike Plante, Kim Yutani, John Scurti, Scott Cohen, Armie Hammer, Aja Naomi King, Caroline Libresco, John Nein, Landon Zakheim Mary Stuart Masterson Jackie Earle Haley, Gabrielle Union, Mike Plante, Charlie Reff, Kim Yutani Mark Boone Jr. -

Living Entanglements and the Ecological Thought in the Works Of

LIVING ENTANGLEMENTS AND THE ECOLOGICAL THOUGHT IN THE WORKS OF PAUL KINGSNORTH, TOM MCCARTHY, AND ALI SMITH By Garrett Joseph Peace James J. Arnett Andrew D. McCarthy Associate Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Heather M. Palmer Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) LIVING ENTANGLEMENTS AND THE ECOLOGICAL THOUGHT IN THE WORKS OF PAUL KINGSNORTH, TOM MCCARTHY, AND ALI SMITH By Garrett Joseph Peace A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts: English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee May 2021 ii ABSTRACT In my thesis, I use the work of Donna Haraway, Timothy Morton, Karen Barad, and Anna Tsing to explore how three contemporary British novelists—Paul Kingsnorth, Tom McCarthy, and Ali Smith—deal with the representational and ethical challenges of writing about nature and climate change within the Anthropocene. The question of how to live and write now is a prominent thread in all their works, which show, in both form and content, the entanglements of ecology, materiality, locality, nationality, and personal identity. In doing so, their stories enable readers to engage with what Morton calls the “ecological thought,” i.e. “a practice and process of becoming fully aware of how human beings are connected with other beings,” and provoke us, as Haraway puts it, “to be truly present . as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.” iii DEDICATION For my parents, Robin and James. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As many of the writers present in these pages show us, to be human is to exist in a state of interconnection. -

Post-Postmodern Cinema at the Turn of the Millennium: Paul Thomas Anderson’S Magnolia

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, vol. 24, 2020. Seville, Spain, ISSN 1133-309-X, pp. 1-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/REN.2020.i24.01 POST-POSTMODERN CINEMA AT THE TURN OF THE MILLENNIUM: PAUL THOMAS ANDERSON’S MAGNOLIA JESÚS BOLAÑO QUINTERO Universidad de Cádiz [email protected] Received: 20 May 2020 Accepted: 26 July 2020 KEYWORDS Magnolia; Paul Thomas Anderson; post-postmodern cinema; New Sincerity; French New Wave; Jean-Luc Godard; Vivre sa Vie PALABRAS CLAVE Magnolia; Paul Thomas Anderson; cine post-postmoderno; Nueva Sinceridad; Nouvelle Vague; Jean-Luc Godard; Vivir su vida ABSTRACT Starting with an analysis of the significance of the French New Wave for postmodern cinema, this essay sets out to make a study of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia (1999) as the film that marks the beginning of what could be considered a paradigm shift in American cinema at the end of the 20th century. Building from the much- debated passing of postmodernism, this study focuses on several key postmodern aspects that take a different slant in this movie. The film points out the value of aspects that had lost their meaning within the fiction typical of postmodernism—such as the absence of causality; sincere honesty as opposed to destructive irony; or the loss of faith in Lyotardian meta-narratives. We shall look at the nature of the paradigm shift to link it to the desire to overcome postmodern values through a recovery of Romantic ideas. RESUMEN Partiendo de un análisis del significado de la Nouvelle Vague para el cine postmoderno, este trabajo presenta un estudio de Magnolia (1999), de Paul Thomas Anderson, como obra sobre la que pivota lo que se podría tratar como un cambio de paradigma en el cine estadounidense de finales del siglo XX. -

22Nd NFF Announces Screenwriters Tribute

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NANTUCKET FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES TOM MCCARTHY TO RECEIVE 2017 SCREENWRITERS TRIBUTE AWARD NICK BROOMFIELD TO BE RECOGNIZED WITH SPECIAL ACHIEVEMENT IN DOCUMENTARY STORYTELLING NFF WILL ALSO HONOR LEGENDARY TV CREATORS/WRITERS DAVID CRANE AND JEFFREY KLARIK WITH THE CREATIVE IMPACT IN TELEVISION WRITING AWARD New York, NY (April 6, 2017) – The Nantucket Film Festival announced today the honorees who will be celebrated at this year’s Screenwriters Tribute—including Oscar®-winning writer/director Tom McCarthy, legendary documentary filmmaker Nick Broomfield, and ground-breaking television creators and Emmy-nominated writing team David Crane and Jeffrey Klarik. The 22nd Nantucket Film Festival (NFF) will take place June 21-26, 2017, and celebrates the art of screenwriting and storytelling in cinema and television. The 2017 Screenwriters Tribute Award will be presented to screenwriter/director Tom McCarthy. McCarthy's most recent film Spotlight was awarded the Oscar for Best Picture and won him (and his co-writer Josh Singer) an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. McCarthy began his career as a working actor until he burst onto the filmmaking scene with his critically acclaimed first feature The Station Agent, starring Peter Dinklage, Patricia Clarkson, Bobby Cannavale, and Michelle Williams. McCarthy followed this with the equally acclaimed film The Visitor, for which he won the Spirit Award for Best Director. He also shared story credit with Pete Docter and Bob Peterson on the award-winning animated feature Up. Previous recipients of the Screenwriters Tribute Award include Oliver Stone, David O. Russell, Judd Apatow, Paul Haggis, Aaron Sorkin, Nancy Meyers and Steve Martin, among others. -

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23Rd, 2019

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23rd, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 24th ANNUAL NANTUCKET FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES FEATURE FILM LINEUP DANNY BOYLE’S YESTERDAY TO OPEN FESTIVAL ALEX HOLMES’ MAIDEN TO CLOSE FESTIVAL LULU WANG’S THE FAREWELL TO SCREEN AS CENTERPIECE DISNEY•PIXAR’S TOY STORY 4 PRESENTED AS OPENING FAMILY FILM IMAGES AVAILABLE HERE New York, NY (April 23, 2019) – The Nantucket Film Festival (NFF) proudly announced its feature film lineup today. The opening night selection for its 2019 festival is Universal Pictures’ YESTERDAY, a Working Title production written by Oscar nominee Richard Curtis (Four Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually, and Notting Hill) from a story by Jack Barth and Richard Curtis, and directed by Academy Award® winner Danny Boyle (Slumdog Millionaire, Trainspotting, 28 Days Later). The film tells the story of Jack Malik (Himesh Patel), a struggling singer-songwriter in a tiny English seaside town who wakes up after a freak accident to discover that The Beatles have never existed, and only he remembers their songs. Sony Pictures Classics’ MAIDEN, directed by Alex Holmes, will close the festival. This immersive documentary recounts the thrilling story of Tracy Edwards, a 24-year-old charter boat cook who became the skipper of the first ever all-female crew to enter the Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race. The 24th Nantucket Film Festival runs June 19-24, 2019, and celebrates the art of screenwriting and storytelling in cinema. A24’s THE FAREWELL, written and directed by Lulu Wang, will screen as the festival’s Centerpiece film. -

Confessions of a Dangerous Mind

CONFESSIONS OF A DANGEROUS MIND a screenplay by Charlie Kaufman based on CONFESSIONS OF A DANGEROUS MIND an unauthorized biography by Chuck Barris third draft (revised) May 5, 1998 MUSIC IN: OMINOUS ORCHESTRAL TEXT, WHITE ON BLACK: This film is a reenactment of actual events. It is based on Mr. Barris's private journals, public records, and hundreds of hours of taped interviews. FADE IN: EXT. NYC STREET - NIGHT SUBTITLE: NEW YORK CITY, FALL 1981 It's raining. A cab speeds down a dark, bumpy side-street. INT. CAB - CONTINUOUS Looking in his rearview mirror, the cab driver checks out his passenger: a sweaty young man in a gold blazer with a "P" insignia over his breast pocket. Several paper bags on the back seat hedge him in. The young man is immersed in the scrawled list he clutches in his hand. A passing street light momentarily illuminates the list and we glimpse a few of the entries: double-coated waterproof fuse (500 feet); .38 ammo (hollowpoint configuration); potato chips (Lays). GONG SHOW An excerpt from The Gong Show (reenacted). The video image fills the screen. We watch a fat man recite Hamlet, punctuating his soliloquy with loud belching noises. The audience is booing. Eventually the man gets gonged. Chuck Barris, age 50, hat pulled over his eyes, dances out from the wings to comfort the agitated performer. PERFORMER Why'd they do that? I wasn't done. BARRIS (AGE 50) I don't understand. Juice, why'd you gong this nice man? JAYE P. MORGAN Not to be. That is the answer. -

Screenwriting: the Feature Film

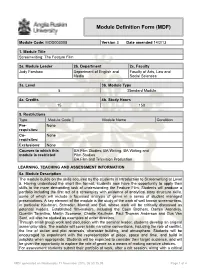

Module Definition Form (MDF) Module Code: MOD003008 Version 3 Date amended 14/2/13 1. Module Title Screenwriting: The Feature Film 2a. Module Leader 2b. Department 2c. Faculty Judy Forshaw Department of English and Faculty of Arts, Law and Media Social Sciences 3a. Level 3b. Module Type 5 Standard Module 4a. Credits 4b. Study Hours 15 150 5. Restrictions Type Module Code Module Name Condition Pre- None requisites: Co- None requisites: Exclusions: None Courses to which this BA Film Studies; BA Writing; BA Writing and module is restricted Film Studies BA Film and Television Production LEARNING, TEACHING AND ASSESSMENT INFORMATION 6a. Module Description The module builds on the skills acquired by the students in Introduction to Screenwriting at Level 5. Having understood the short film format, students now have the opportunity to apply their skills to the more demanding task of understanding the Feature Film. Students will produce a portfolio including the first act of a screenplay with evidence of analytical story structure skills, some of which will include a focussed analysis of genre in a series of student managed presentations. A key element of the module is the study of the work of well known screenwriters, in particular Kaufman, Schrader, Mamet and Ball, whose work will be critically discussed as potential models. Established film-makers, including the Coen Brothers, Darren Aronsksy, Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, Charlie Kaufman, Paul Thomas Anderson and Gus Van Sant, will also be studied as examples of writer directors. Through small group work and discussion with the seminar leader, students develop an original screenplay idea. -

Projection and Control in the Works of Charlie Kaufman

In this careful study of the works of Charlie Kaufman, Larson sets up the problem of the mind's relationship to reality, then explores it through a series of related concepts—how we project ourselves into reality, how we try to control it, and how this limits our ability to connect to others. (Instructor: Victoria Olsen) PLAYING WITH PEOPLE: PROJECTION AND CONTROL IN THE WORKS OF CHARLIE KAUFMAN Audrey Larson ohn Malkovich is falling down a dark, grimy tunnel. With a crash, he finds himself in a restaurant, the camera panning up from a plate set with a perfectly starched napkin to a pair of large Jbreasts in a red dress and a delicate wrist hanging in the air like a question mark. The camera continues panning up to the face that belongs to this body, the face of—John Malkovich. Large-breasted Malkovich looks sensually at the camera and whispers, “Malkovich, Malkovich,” in a sing-song whisper. A waiter pops in, also with the face of Malkovich, and asks, “Malkovich? Malkovich, Malkovich?” The real Malkovich looks down at the menu—every item is “Malkovich.” He opens his mouth, but only “Malkovich,” comes out. A look of horror dawns on his face as the camera jerks around the restaurant, focusing on different groups of people, all with Malkovich’s face. He gets up and starts to run, but stops in his tracks at the sight of a jazz singer with his face, lounging across a piano and tossing a high-heeled leg up in the air. A whimper escapes the real Malkovich. -

True and False New Realities in the Films of Wes Anderson, Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 121–131 True and False New Realities in the Films of Wes Anderson, Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman André Crous University of Stellenbosch (South Africa) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The filmmakers of the French Nouvelle Vague, in the spirit of post- war modernism, wanted to get at the truth of everyday life, and braved oncoming traffic to capture people living real lives. Since the turn of the millennium, Wes Anderson, Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman have taken the opposite track, showing a remarkable tendency to undermine their own representations of reality – often humorously collapsing the boundaries between the actual and fictional worlds. The particular filmmakers never content themselves with simple exercises in mimesis, but instead openly acknowledge the elusive objective of faithfully representing reality: examples include the subversively deceptively Godardian cut-away of a film set in Anderson’s Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), the symbiotic relationship between the diegetic writing of two screenplays and the events unfolding around the characters in Jonze’s Adaptation (2002), and the multiple mise- en-abyme structure of Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York (2008). In the course of their films, Anderson, Jonze and Kaufman playfully yet confidently turn our perception of diegetic reality on its head, placing emphasis on the idea of “performance” – as it relates to the characters as well as the films themselves. Introduction The late 1950s and the early 1960s saw a handful of French directors setting out to revitalize a film industry whose output, according to them, had become dull and conventional. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

ANNUAL REPORT for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2019

ST. RITA OF CASCIA HIGH SCHOOL ANNUAL REPORT for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2019 TRUTH UNITY LOVE Veritas Unitas Caritas ADMINISTRATION President TRUTH UNITY LOVE James Quaid, Ph.D. VeritasUnitas Caritas Chairman of the Board Ernest J. Mrozek, ‘71 Vice President of Academics Wes Benak, ‘81 Vice President of Student Life CONTENT Josh Blaszak ‘02 Vice President of Finance SCHOOL NEWS Eileen Spulak OFFICE OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT page 1 | A Message from Jim Quaid Director of Institutional Advancement page 2 | Fall Sports Wrap Up Jim Juchcinski ‘97 Director of Annual Appeal and Major Gifts page 4 | The Caritas Project John Schmitt ‘84 Associate Director of Advancement & page 6 | St. Rita Welcomes New President Director of Advancement Communications Laura Fleck page 8 | Students Explore Career Opportunities Database Manager & Director of Special Events Mary Gal Carroll Beyond the Classroom Director of Alumni & Donor Relations page 10 | Faculty Spotlight: Robyn Kurnat Rob Gallik ‘10 BOARD OF DIRECTORS ALUMNI/ADVANCEMENT NEWS Ernest Mrozek ‘71 (Chairman) Victoria Barrios page 12 | Career Day James Brasher ‘71 Bernard DelGiorno HON Lawrence Doyle ‘68 page 14 | Mustangs in the MLB James Gagnard ‘64 Thomas Healy ‘83 page 15 | A Message from Jim Juchcinski ‘97 Catharine Hennessy David Howicz ‘84 Nicholas LoMaglio ‘04 page 16 | Keeping Track Donald Mrozek ‘65 Clare Napleton page 17 | 1905 Guild Charles Nash ‘71 John O’Neill ‘79 page 18 | Summary Financial Statement Fr. Anthony Pizzo, O.S.A. Timothy Ray ‘87 Br. Joe Ruiz, O.S.A. page 19 | Honor Roll of Donors Stephen Schaller ‘83 Fr. Bernard Scianna, O.S.A. -

F L O Y D M E M O R Ia L L Ib R

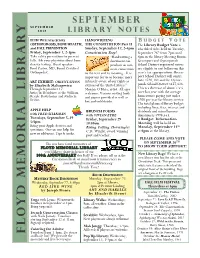

SEPTEMBER s E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 7 Library NOTES ELIH WELLNESS SERIES HANDWRITING B UDGET V OTE OSTEOPOROSIS, BONE HEALTH, THE CONSTITUTION Part II The Library Budget Vote is and FALL PREVENTION Sunday, September 17, 2-4pm scheduled to be held on Tuesday, Friday, September 1, 2-3pm Constitution Day! September 26th from 2pm until Take safety precautions to prevent “Handwriting a 8pm in the library Meeting Room. falls. Ask your physician about bone document can Greenport and Oysterponds density testing. Guest speaker: produce an inti- School District registered voters Fred Carter, MD, Board Certified mate connection are eligible to cast ballots on this Orthopedist. year’s tax appropriation. Green- to the text and its meaning...It is important for us to become more port School District will contri- ART EXHIBIT: ORIENTATION intensely aware of our rights as bute $520,184 and the Oyster- by Elizabeth Malunowicz citizens of the United States.” ponds School District $457,628. l i bThrough r a ry September 17 Morgan O’Hara, artist. All ages This is a decrease of about 7.5% Artist-in-Residence at the William over last year with the average welcome. Various writing tools Steeple Davis home and studio in and papers provided as well as homeowner paying just under Orient. hot and cold drinks. $200 per year for library service. The total planned library budget including fines, fees, interest and APPLE HELP BRUNCH POEMS dividends and miscellaneous with FRED SHARMAN with VIVIAN EYRE donations is $998,653. Tuesdays, September 5–19 Friday, September 29 A Budget Information 3-5pm 10:30am Meeting will be held on Bring your Apple devices and Rising, Falling, Hovering by Monday, September 11th questions.