ICRIER Working Paper 267; September

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Pakistan's Automobile Industry

History of Pakistan’s Automobile Industry Following international trends, the automobile industry in Pakistan showed substantial growth in the years under review. The growth was aided by favorable government policies during this period and levy of lower import duties on raw material inputs and on intermediate products. A significant rise in demand for automobiles, propelled at least partly by easy availability of auto leases and loans from banks and leasing companies at low financial cost, was instrumental in the fast growth of the sector. The expansion in the sector, besides boosting the country‟s industrial output, also provided significant direct and indirect employment opportunities. In the past years, there has been a high growth of more than 40 percent per year in the automobile market. The growth declined somewhat in 2008 and 2009 due mainly to a dip in demand because of rising prices and lease financing becoming expensive for the consumers. Pakistan Car Industry The first automobile plant was set up in May 1949 by General Motor & Sales Co. It was set up on an experimental basis, however grew into an assembly plant. Seeing such progress, three major auto manufacturers from the US collaborated with Pakistani business men to set up; Ali Automobiles to manufacture Ford Products in 1955, Haroon Industries to assemble Chrysler Dodge cars in 1956, Khandawalla Industries to assemble American Motor Products in 1962, and Mack Trucks Plant in 1963. However towards the end of the seventies all automobile assembly in Pakistan stopped, until 1983 when Pak Suzuki started manufacturing their vehicles in Pakistan. Further Toyota Indus Motors was set up in 1990, followed by Honda. -

Board of Directors

8 Board of Directors Mr. Yusuf H. Shirazi Chairman Mr. Shirazi is a Law graduate (LLB) with BA (Hons) and JD (Diploma in Journalism) from Punjab University and AMP Harvard. He served in the financial services of the Central Superior Services of Pakistan for eight years. He is the author of five books including ‘Aid or Trade’ adjudged by the Writers Guild as the best book of the year and continues to be a columnist, particularly on economy. Mr. Shirazi is the Chairman of Atlas Group, which among others, has joint ventures with Honda, GS Yuasa, MAN and Total. He has been the President Karachi Chamber of Commerce and Industries for two terms. He has been the founder member of Karachi Stock Exchange, Lahore Stock Exchange and International Chamber of Commerce and Industry. He has been on the Board of Harvard Business School Alumni Association and is the Founder President of Harvard Club of Pakistan and Harvard Business School Club of Pakistan. He has been a visiting Faculty Member at National Defense College, Navy War College and Pakistan Administrative Staff College. He has been on the Board of Governors of LUMS, GIK and FC College. Previously he also served, among others on the Board of Fauji Foundation Institute of Management and Computer Sciences (FFIMCS) and Institute of Space Technology - Space & Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO). Mr.Takeharu Aoki President & CEO Mr. Aoki is President & Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Honda Atlas Cars (Pakistan) Ltd. He has been associated with Honda Motor Company Limited, Japan for last 22 years and has rich experience of Sales & Marketing. -

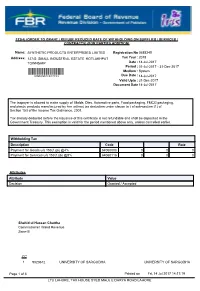

153(4) (Order to Grant / Refuse Reduced Rate of Withholding on Supplies / Services / Contracts) (For Parties Addition)

153(4) (ORDER TO GRANT / REFUSE REDUCED RATE OF WITHHOLDING ON SUPPLIES / SERVICES / CONTRACTS) (FOR PARTIES ADDITION) Name: SYNTHETIC PRODUCTS ENTERPRISES LIMITED Registration No 0688349 Address: 127-S SMALL INDUSTRIAL ESTATE KOTLAKHPAT Tax Year : 2018 TOWNSHIP Date : 14-Jul-2017 Period : 01-Jul-2017 - 31-Dec-2017 Medium : System Due Date : 14-Jul-2017 Valid Upto : 31-Dec-2017 Document Date 14-Jul-2017 The taxpayer is allowed to make supply of Molds, Dies, Automotive parts, Food packaging, FMCG packaging, and plastic products manufactured by him without tax deduction under clause (a ) of sub-section (1) of Section 153 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001. Tax already deducted before the issuance of this certificate is not refundable and shall be deposited in the Government Treasury. This exemption is valid for the period mentioned above only, unless cancelled earlier. Withholding Tax Description Code Rate Payment for Goods u/s 153(1)(a) @4% 64060008 0 0 0 Payment for Services u/s 153(1)(b) @8% 64060116 0 0 0 Attributes Attribute Value Decision Granted / Accepted Shahid ul Hassan Chattha Commissioner Inland Revenue Zone-III CC 1 9020612 UNIVERSITY OF SARGODHA UNIVERSITY OF SARGODHA Page 1 of 6 Printed on Fri, 14 Jul 2017 14:17:19 LTU LAHORE, TAX HOUSE SYED MAUJ E DARYA ROAD LAHORE 153(4) (ORDER TO GRANT / REFUSE REDUCED RATE OF WITHHOLDING ON SUPPLIES / SERVICES / CONTRACTS) (FOR PARTIES ADDITION) Name: SYNTHETIC PRODUCTS ENTERPRISES LIMITED Registration No 0688349 Address: 127-S SMALL INDUSTRIAL ESTATE KOTLAKHPAT Tax Year : 2018 TOWNSHIP -

Financial Analysis of Toyota Indus Motor Company

Financial Analysis of Toyota Indus Motor Company 2017 Financial Analysis of Toyota Indus Motor Company Financial Year 2011-2016 Ayesha Majid Lahore School of economics 5/1/2017 Financial Analysis of Toyota Indus Motor Company i Table of Contents Preamble .................................................................................................................... 1 Categories of Financial Ratios Analysed ................................................................ 1 Limitations .............................................................................................................. 2 Toyota Indus Motors................................................................................................... 3 Company Profile ..................................................................................................... 3 Financial Profile ...................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 Mission Statement ............................................................................................... 5 Vision Statement ................................................................................................. 5 Slogan ................................................................................................................. 5 Quote Summary as on 1st May 2017 .......................................................................... 6 -

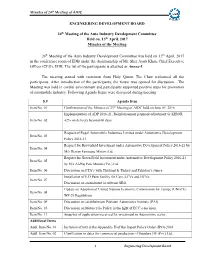

ENGINEERING DEVELOPMENT BOARD 24Th Meeting of the Auto

th Minutes of 24 Meeting of AIDC ENGINEERING DEVELOPMENT BOARD 24th Meeting of the Auto Industry Development Committee Held on, 13th April, 2017 Minutes of the Meeting 24th Meeting of the Auto Industry Development Committee was held on 13th April, 2017 in the conference room of EDB under the chairmanship of Mr. Sher Ayub Khan, Chief Executive Officer (CEO), EDB. The list of the participants is attached as Annex-I. The meeting started with recitation from Holy Quran. The Chair welcomed all the participants. After introduction of the participants, the forum was opened for discussion. The Meeting was held in cordial environment and participants supported positive steps for promotion of automobile industry. Following Agenda Items were discussed during meeting. S.# Agenda Item Item No. 01 Confirmation of the Minutes of 23rd Meeting of AIDC held on June 09, 2016 Implementation of ADP 2016-21, Reimbursement payment adjustment @ KIBOR Item No. 02 +2% on delivery beyond 60 days Request of Regal Automobile Industries Limited under Automotive Development Item No. 03 Policy 2016-21 Request for Brownfield Investment under Automotive Development Policy 2016-21 by Item No. 04 M/s Dewan Farooque Motors Ltd. Request for Green Field Investment under Automotive Development Policy 2016-21 Item No. 05 by M/s Al-Haj Faw Motors (Pvt.) Ltd Item No. 06 Discussion on FTA’s with Thailand & Turkey and Pakistan’s stance. Installation of E.D Paint facility for Cars, LCVs and HCVs: Item No. 07 Discussion on amendment in relevant SRO. Update on Adoption of United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Item No. -

Enabling Economic Corridors Through Sustainable Transport Sector Development

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 49063 August 2019 Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Enabling Economic Corridors through Sustainable Transport Sector Development Prepared by NTU International Aalborg, Denmark For Ministry of Communications Engineering Development Board, Ministry of Industries & Production This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. FINAL DRAFT NATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR VEHICLE GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN LICENCING MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATIONS ENGINEERING DEVELOPMENT BOARD GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF INDUSTRIES & PRODUCTION The preparation of these Guidelines was assisted by a technical assistance grant financed by the UK Department for international Development (DFID) and administered by the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The document does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB, DFID or the Government concerned, and ADB, DFID and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. Published by: Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Communications, Islamabad August 2019 www.communication.gov.pk Guidelines for Vehicle Licencing FOREWORD The National Guidelines for Vehicle Licencing have been developed to assist the Government of Pakistan (GoP) to improve motor vehicle safety. Motor vehicles provide many benefits to modern society, enhancing connectivity and facilitating economic development. There has been a rapid increase in vehicle numbers in recent years, and this is projected to continue. With the increase in vehicle numbers, there has come an increase in deaths and injuries. It is essential that measures be taken arrest this trend by ensuring that vehicles are constructed, maintained and operated safely. Under the laws of Pakistan most motor vehicles must be registered if they are to be used on public roads. -

Monthly Magazine

Issue 6, January 2007 With circulation of over 31,000+ copies every month Monthly Magazine Pakistan Rs. 50 U.A.E. AED 5 International US$ 5 )NTERVIEWWITH 'ET TOGETHERS (YUNDAI$EWAN-OTORS 3POTTED %XPLAINING#64 (OW2ADIATORS7ORK www.pakwheels.com January 2007 www.pakwheels.com January 2007 www.pakwheels.com January 2007 safaa.u.t.o.m.o.b.i.l.e.s Deals in all kinds of New and Used Automobiles R 111/2, Khalid Bin Walid Road, Block 2, P.E.C.H.S. Karachi. Ph: 4529256, 4388788, 4388799 Fax: 4559642 E-mail: [email protected] www.pakwheels.com January 2007 www.pakwheels.com January 2007 3)2%.(/2.3%2)%3 !,!2-,)'(43%2)%3 ,)'(4"!23%2)%3 Editors Note FASCOMCOM % MAILAUTOLINE &AX #ELL 4EL -!*INNAH2OAD +ARACHI ' 2IMPA0LAZA (EAD/FFICE ,%$LIGHT Editor #ARELECTRONICHORN Well, well this time with the celebrations of New Year we’ve tweaked our traditional cover story from wheels into wheels! YES, Superbikes is ,%$ what we have featured this month, though most of them are stock but still hell fast. This issue, along with our usual stuff, we did an interview Jag 8$ ! with Hyundai Dewan Motors CEO and MD so make sure you have a look at it. 5LTRA THINREVOLVINGLIGHTBAR To fill the missing gap we have included quite a few more short articles for your reading pleasure for which we have been receiving Associate Editor complains that there are too less of articles – also a regular review of Imported Toyota Corolla can be found on page 0! Sania Zafar 4"$ '! $ 3TREETEAGLE,%$LIGHTBAR Usually December is a slow monthly mainly due to end of the year with Christmas & Eid coming up. -

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Atlas Honda is the market leader in the motorcycle industry and its efficient working shows this position can be maintained and improved even further in the years to come. Its nearest competitors have still a long way to reach Atlas. The reasons behind this are the quality standards at Atlas, its committed workforce and ample chances of growth at all levels in the organization. Atlas Honda has this exemplary tradition of orientation which gives its new recruits a clear picture of the industry and production employed at the industry. I would like to appreciate Atlas Honda on their efforts and wish them future success (Amen). This report contains the workings of the departments that I visited during the orientation program at Atlas Honda. This report also has suggestions for further improvements to the current working and processes in the organization. 1 ATLAS HONDA ± COMPANY PROFILE Atlas Honda Limited is a joint venture between the Atlas Group and Honda Motor Co. Japan. The company was created by the merger of Panjdarya Limited, Sheikhupura successor to Atlas Epak Ltd., Dhaka since taken over by the Government of Bangladesh and Atlas Autos Ltd. in 1991. Both these motorcycle manufacturing concerns were established by the Atlas Group. Atlas Honda Limited manufactures and markets Honda motorcycles in collaboration with Honda Motor Company. The Company also manufactures shock absorbers under a Technical Assistance Agreement with Showa of Japan, world leaders in shock absorber technology. Honda motorcycles are by far the best selling motorcycles in the country with an unmatched reputation for high quality, reliability and after-sales-service. -

Updated July 2021 1

2021 Honda Digital FactBook Updated July 2021 1 Table of Contents Key Locations and Contacts by Region 2 Public Relations Directory North America: Automobile North America: Power Equipment Torrance, CA Motorsports Power Equipment American Honda Motor Co., Inc. Chuck Schifsky Alpharetta, GA 1919 Torrance Boulevard [email protected] American Honda Motor Co., Inc. Torrance, CA 90501-2746 4900 Marconi Drive Safety, Regulatory and Recalls Alpharetta, GA 30005 Phone: 310-783-3170 Fax: 310-783-3622 Chris Martin Jessica Fini [email protected] Phone: 770-712-3082 Fax: 678-339-2670 [email protected] Honda and Acura: Regional North America: Powersports Shigeki Endo Lynn Seely [email protected] (Midwest Media Relations) Torrance, CA [email protected] American Honda Motor Co., Inc. Honda 4900 Marconi Drive Natalie Kumaratne Chris Naughton Alpharetta, GA 30005 [email protected] (North East Media Relations) Phone: 310-783-3846 [email protected] Carl Pulley Brandon Wilson (West Coast Media Relations) [email protected] [email protected] Colin Miller Acura (2-Wheel, On/Off-Road) Andrew Quillin [email protected] [email protected] Ryan Dudek Karina Gonzalez (2-Wheel, Off-Road) (West Coast Media Relations) [email protected] [email protected] Ben Hoang (ATV, Side-by-Side) [email protected] 3 Public Relations Directory North America: Corporate Communications Public Affairs Torrance, CA Ohio Manufacturing and R&D: Washington, -

Overview Association Major Players

Brief on Automotive Sector Overview The auto sector is considered the sixth largest manufacturing sector in Pakistan and is therefore of prime importance to the economy of Pakistan. Pakistan’s automotive industry started with an automobile plant set up by General Motors in 1949. To achieve 75 per cent local content levels, auto manufacturers started to look for local sourcing. They also started to provide auto parts manufacturers with technical assistance to ensure quality and uninterrupted supply, which led to the development of the auto vending industry. Pakistan automobile industry is the sixth largest manufacturing sub‐sector with annual contribution of 2.8 percent in GDP. Automotive sector still thrives to make significant contribution to the domestic economy in form of foreign investments, foreign exchange earnings, employment, and revenue generation. Association • Pakistan Automotive Manufacturers Association (PAMA) • Pakistan Association of Automotive Parts & Accessories Manufacturers (PAAPAM) Major Players Pak Suzuki Co. Ltd Atlas Honda Ltd. Indus Motor Co. Ltd. Plum Qingqi Motors Ltd. Honda Atlas Cars (Pakistan) Ltd. Fateh Motors Ltd. Sigma Motors Ltd. Ravi Automobile Pvt. Ltd. Ghandhara Industries Ltd. Sazgar Engineering Works Ltd. Ghandhara Nissan Ltd. Orient Automotive Industries Pvt. Ltd. Master Motor Corporation Ltd. Eiffel Industries Ltd. Millat Tractors Ltd. Yamaha Motor Pakistan Pvt. Ltd. Al-Ghazi Tractors Ltd. United Auto Industries Pvt. Ltd. Hyundai Nishat Motor Pvt. Ltd. Hinopak Motors Limited Ghandhara DF (Pvt) Ltd. Fuso Master Motor Pvt Ltd. Afzal Motors Pvt Ltd PM Auto Industries Daewoo Pak Motors (Pvt) Ltd. Al Haj FAW Motors (Pvt) Ltd. Al-Ghazi Tractors Ltd MTW Pak Assembling Industries (Pvt) Ltd. -

Mr. Aamir H Shirazi

Mr. Aamir H Shirazi Chairman Mr. Aamir H. Shirazi is the President of Atlas Group. He graduated from Claremont Mckenna College, California and completed his OPM from Harvard Business School. He was the Chief Executive of Atlas Honda Limited for over ten years. He was also appointed as a professional director on the Board of Lahore Stock Exchange for two consecutive terms by the Securities & Exchange Commission of Pakistan. He has been Honorary Consul General of Japan, Lahore since 2002. He is also on the board of Murree Brewery Company Limited and Total Parco Pakistan Limited. Mr. Hironobu Yoshimura President /CEO Honda Atlas Cars (Pakistan) Limited Mr. Hironobu Yoshimura has been associated with Honda Motor Company Limited, Japan for more than 30 years. He joined Honda in 1988 and began his career in Service Technology Division in Japan. Mr. Hironobu Yoshimura has experience in the Automobile industry, having worked in several planning divisions. In his previous assignment, he has worked as Department Manager at Automobile Marketing Planning Office in Honda Motor Company Limited, Japan. HE joined on the Board of Honda Atlas Cars (Pakistan) Limited as President & Chief Executive Office from November 1, 2017. Mr. Yoshimura is graduate from Sophia University, Japan. Mr. Saquib H. Shirazi Director & Senior Advisor Mr. Saquib H. Shirazi is a graduate of the Wharton School of Finance and did his MBA from the Harvard Business School. He started his career with the Bank of Tokyo and was subsequently appointed as the CEO of Atlas BOT Investment Bank. In addition to being a member of the Atlas Group, he is a Director of Pakistan Cables and Vice Chairman of Pakistan Business Council. -

Mr. Aamir H. Shirazi Chairman Mr. Hironobu Yoshimura President

Mr. Aamir H. Shirazi Chairman Mr. Aamir H. Shirazi is the President of Atlas Group. He graduated from Claremont Mckenna College and attended the OPM at the Harvard Business School. He has over 35 years of corporate management experience. He has to his credit, work experience in Honda America, besides working at various positions in Atlas Group, including serving as the Chief Executive of Atlas Honda Limited for eleven years. He is currently Chairman of Honda Atlas Cars, Atlas Honda, Atlas Engineering and Atlas Autos. He also serves on the Boards of Shirazi Investment (Group Holding Company), Shirazi Trading, and Murree Brewery Company Limited. He is a member of the Board of Governors, Lahore University of Management Science and member Syndicate, University of Engineering & Technology. He was also appointed as a Professional Director on the Board of Lahore Stock Exchange for two consecutive terms by the Securities & Exchange Commission of Pakistan. He has been serving the Honorary Consul General of Japan in Lahore, since 2002 and is the Patron-in-Chief, Pakistan Japan Cultural Association, Lahore. Mr. Hironobu Yoshimura President & CEO Mr. Hironobu Yoshimura has been associated with Honda Motor Company Limited, Japan for more than 32 years. He joined Honda in 1988 and began his career in Service Technology Division, Honda Motor Company, Japan. Mr. Hironobu Yoshimura has extensive experience in the Automobile industry, having worked in several planning divisions. In his previous assignment, he has worked as Department Manager at Automobile Marketing Planning Office in Honda Motor Company Limited, Japan and General Manager Asian Honda Motor Co. Ltd., Thailand.