The Journal of the Mail Research Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIEVAL ARMOR Over Time

The development of MEDIEVAL ARMOR over time WORCESTER ART MUSEUM ARMS & ARMOR PRESENTATION SLIDE 2 The Arms & Armor Collection Mr. Higgins, 1914.146 In 2014, the Worcester Art Museum acquired the John Woodman Higgins Collection of Arms and Armor, the second largest collection of its kind in the United States. John Woodman Higgins was a Worcester-born industrialist who owned Worcester Pressed Steel. He purchased objects for the collection between the 1920s and 1950s. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 3 Introduction to Armor 1994.300 This German engraving on paper from the 1500s shows the classic image of a knight fully dressed in a suit of armor. Literature from the Middle Ages (or “Medieval,” i.e., the 5th through 15th centuries) was full of stories featuring knights—like those of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, or the popular tale of Saint George who slayed a dragon to rescue a princess. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 4 Introduction to Armor However, knights of the early Middle Ages did not wear full suits of armor. Those suits, along with romantic ideas and images of knights, developed over time. The image on the left, painted in the mid 1300s, shows Saint George the dragon slayer wearing only some pieces of armor. The carving on the right, created around 1485, shows Saint George wearing a full suit of armor. 1927.19.4 2014.1 WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 5 Mail Armor 2014.842.2 The first type of armor worn to protect soldiers was mail armor, commonly known as chainmail. -

Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries

Roman Armour Chain Mail Armour Transitional Armour Plate Mail Armour Milanese Armour Gothic Armour Maximilian Armour Greenwich Armour Armour Diagrams Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Replaced old chain mail armour. Made up of dozens of small metal plates, and held together by leather laces. Lorica Segmentata Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers as protection for the lower legs and knees. Attached to legs by leather straps. Roman Greaves Page 1 ?BC - 400AD Used by Roman Legionaries. Handle is located behind the metal boss, which is in the centre of the shield. The boss protected the legionaries hand. Made from several wooden planks stuck together. Could be red or blue. Roman Shield Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Includes cheek pieces and neck protection. Iron helmet replaced old bronze helmet. Plume made of Hoarse hair. Roman Helmet Page 1 100AD - 400AD Soldier on left is wearing old chain mail and bronze helmet. Soldiers on right wear newer iron helmets and Lorica Segmentata. All soldiers carry shields and gladias’. Roman Legionaries Page 1 400BC - 400AD Used as primary weapon by most Roman soldiers. Was used as a thrusting weapon rather than a slashing weapon Roman Gladias Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers. Decorations depict muscles of the body. Made out of a single sheet of metal, and beaten while still hot into shape Roman Cuiruss Page 1 ?- 400AD Chain Mail Armour Page 2 400BC - 1600AD Worn by Vikings, Normans, Saxons and most other West European civilizations of the time. -

Semi-Historical Arms and Armor the Following Are Some Notes About The

Semi-Historical Arms and Armor The following are some notes about the weapons and armor tables in D&D 5th edition, as they pertain to their relationship to modern understandings of historical arms and armor. In general, 5th edition is far more accurate to ancient and medieval sources regarding these topics than prior editions, but for the sake of balance and ease of play without the onerous restrictions of reality, there are still some expected incongruences. This article attempts to explain some particular facets about the use of arms and armor throughout our long, shared history, and to offer some suggestions (imbalanced as they may be) on how such items would have been used in particular times and places. A note on generalities: One of the best things 5th edition offers in these tables is the generalization of particular weapons and armor compared to prior editions. Is there a significant, functional difference between a half-sword, arming sword, backsword, wakizashi, tulwar, or any other various forms of predominately one-handed pokey and slashy things with 13 inch, sometimes 14 or 20 or even 30 inch blades? Well, actually yes, but that level of discrimination is often not noticeable in the granularity of the combat mechanics of most systems, and, more importantly, how modern readers often distinguish them is often anachronistic. For instance, almost all straight sword-like weapons, be it arming swords, half-swords, back swords, longswords or even great swords like claymores (but not Messers!) are referred to in ancient and medieval texts (MS I.33, Liberi, etc) as… swords. -

The Terminology of Armor in Old French

1 A 1 e n-MlS|^^^PP?; The Terminology Of Amor In Old French. THE TERMINOLOGY OF ARMOR IN OLD FRENCH BY OTHO WILLIAM ALLEN A. B. University of Illinois, 1915 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ROMANCE LANGUAGES IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1916 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL CO oo ]J1^J % I 9 I ^ I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPER- VISION BY WtMc^j I^M^. „ ENTITLED ^h... *If?&3!£^^^ ^1 ^^Sh^o-^/ o>h, "^Y^t^C^/ BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF. hu^Ur /] CUjfo In Charge of Thesis 1 Head of Department Recommendation concurred in :* Committee on Final Examination* Required for doctor's degree but not for master's. .343139 LHUC CONTENTS Bibliography i Introduction 1 Glossary 8 Corrigenda — 79 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 http://archive.org/details/terminologyofarmOOalle i BIBLIOGRAPHY I. Descriptive Works on Armor: Boeheim, Wendelin. Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Leipzig, 1890, Quicherat, J, Histoire du costume en France, Paris, 1875* Schultz, Alwin. Das hofische Leben zur Zeit der Minnesinger. Two volumes. Leipzig, 1889. Demmin, August. Die Kriegswaffen in ihren geschicht lichen Ent wicklungen von den altesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Vierte Auflage. Leipzig, 1893. Ffoulkes, Charles. Armour and Weapons. Oxford, 1909. Gautier, Leon. La Chevalerie. Viollet-le-Duc • Dictionnaire raisonne' du mobilier frangais. Six volumes. Paris, 1874. Volumes V and VI. Ashdown, Charles Henry. Arms and Armour. New York. Ffoulkes, Charles. The Armourer and his Craft. -

Plate Armor (Edited from Wikipedia)

Plate Armor (Edited from Wikipedia) SUMMARY Plate armor is a historical type of personal body armor made from iron or steel plates, culminating in the iconic suit of armor entirely encasing the wearer. While there are early predecessors, full plate armor developed in Europe during the Late Middle Ages, especially in the context of the Hundred Years' War, from the coat of plates worn over mail suits during the 13th century. In Europe, plate armor reached its peak in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The full suit of armor is thus a feature of the very end of the Middle Ages and of the Renaissance period. Its popular association with the "medieval knight" is due to the specialized jousting armor which developed in the 16th century. Full suits of Gothic plate armor were worn on the battlefields of the Burgundian and Italian Wars. The most heavily armored troops of the period were heavy cavalry such as the gendarmes and early cuirassiers, but the infantry troops of the Swiss mercenaries and the landsknechts also took to wearing lighter suits of "three quarters" munition armor, leaving the lower legs unprotected. The use of plate armor declined in the 17th century, but it remained common both among the nobility and for the cuirassiers throughout the European wars of religion. After 1650, plate armor was mostly reduced to the simple breastplate (cuirass) worn by cuirassiers. This was due to the development of the flintlock musket, which could penetrate armor at a considerable distance. For infantry, the breastplate gained renewed importance with the development of shrapnel in the late Napoleonic wars. -

The Evolution of Plate Armor in Medieval Europe and Its Relation to Contemporary Weapons Development

History, Department of History Theses University of Puget Sound Year 2016 Clad In Steel: The Evolution of Plate Armor in Medieval Europe and its Relation to Contemporary Weapons Development Jason Gill [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/history theses/21 Clad in Steel: The Evolution of Plate Armor in Medieval Europe and its Relation to Contemporary Arms Development Jason Gill History 400 Professor Douglas Sackman 1 When thinking of the Middle Ages, one of the first things that comes to mind for many is the image of the knight clad head to toe in a suit of gleaming steel plate. Indeed, the legendary plate armor worn by knights has become largely inseparable from their image and has inspired many tales throughout the centuries. But this armor was not always worn, and in fact for most of the years during which knights were a dominant force on battlefields plate was a rare sight. And no wonder, for the skill and resources which went into producing such magnificent suits of armor are difficult to comprehend. That said, it is only rarely throughout history that soldiers have gone into battle without any sort of armor, for in the chaotic environment of battle such equipment was often all that stood between a soldier and death. Thus, the history of both armor and weapons is essential to a fuller understanding of the history of war. In light of this importance, it is remarkable how little work has been done on charting the history of soldiers’ equipment in the Middle Ages. -

Knllhtsj^ARMOR

School Picture Sei Number 10 KNllHTSj^ARMOR THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART KNIGHTS IN ARMOR The knight was a warrior on horseback. He and his men had to fight for their liege lord when ever their services were demanded. In return the knight received a grant of land or special privi leges to provide for the cost of his armor, the care of his horse, and the upkeep of his household and retinue. He was considered a member of the nobility and obeyed the code of ethics which we call chivalry. Thus a knight should be loyal, courageous, and courteous as well as skilled in all the arts of war. His obligations to his lord and his own sense of honor brought him into many conflicts. He fought in major wars and countless minor ones. As a Crusader he "took the cross" and journeyed to the Holy Land to fight the infidels. As a champion of the wronged or to settle a point of honor, he challenged another knight in single combat. In quest of adventure he wandered about strange lands as a knight errant. When times were peace ful, he kept in training by fighting in jousts and tournaments. In these enclosed pictures you will see the vari ous activities of the knight, as well as some of his weapons and the armor that provided the pro tection he needed. THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART 1. NORMAN CONQUEST Detail, Bayeux embroidery French, Late 11th Century Bayeux THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART In the time of William the Conqueror, knights seem to have worn armor of rings sewed on heavily padded garments, conical helmets, and carried javelins, swords, and kite-shaped shields. -

From Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Medieval Romance from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight RL 1 Cite textual evidence Romance by the Gawain Poet Translated by John Gardner to support inferences drawn KEYWORD: HML12-228 from the text. RL 3 Analyze VIDEO TRAILER the impact of the author’s choices regarding how to develop and relate elements of a story. RL 5 Analyze how Meet the Author an author’s choices concerning how to structure specific parts of a text contribute to its includes a dozen rough illustrations of overall structure. SL 1c Propel the four poems, though it is impossible conversations by responding to questions that probe reasoning to verify who created the images for this and evidence. L 2b Spell correctly. manuscript. Because Pearl is the most technically brilliant of the four poems, the did you know? Gawain Poet is sometimes also called the Pearl Poet. • The first modern edition of Sir Gawain A Man for All Seasons The Gawain and the Green Knight Poet’s works reveal that he was widely was translated by read in French and Latin and had some J. R. R. Tolkien, a respected scholar of knowledge of law and theology. Although Old and Middle he was familiar with many details of English as well as the medieval aristocratic life, his descriptions author of The Lord of The Gawain Poet’s rich imagination and metaphors also show a love of the the Rings. and skill with language have earned him countryside and rural life. recognition as one of the greatest medieval The Ideal Knight In the person of Sir English poets. -

Armour & Weapons in the Middle Ages

& I, Ube 1bome Hnttquarg Series ARMOUR AND WEAPONS IN THE MIDDLE AGES t Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/armourweaponsinmashd PREFACE There are outward and visible signs that interest in armour and arms, so far from abating, is steadily growing. When- ever any examples of ancient military equipment appear n in sale-rooms a keen and eager throng of buyers invariably | assembles ; while one has only to note the earnest and ' critical visitors to museums at the present time, and to compare them with the apathetic onlookers of a few years J ago, to realize that the new generation has awakened to j j the lure of a fascinating study. Assuredly where once a single person evinced a taste for studying armour many | now are deeply interested. t The books dealing with the subject are unfortunately ' either obsolete, like the works of Meyrick, Planche, Fos- broke, Stothard, and others who flourished during the last L century, or, if recent, are beyond the means of many would-be students. My own book British and Foreign Arms and Armour is now out of print, while the monographs of I Charles ffoulkes, the Rev. Charles Boutell, and | Mr Mr Starkie Gardner are the only reasonably priced volumes j now obtainable. It seemed, therefore, desirable to issue a small handbook which, while not professing in the least to be comprehensive, would contain sufficient matter to give the young student, y the ' man in the street,' and the large and increasing number of persons who take an intelligent interest in the past just j that broad outline which would enable them to understand more exhaustive tomes upon armour and weapons, and 5 ARMOUR AND WEAPONS possibly also to satisfy those who merely wish to glean sufficient information to enable them to discern inac- curacies in brasses, effigies, etc., where the mind of the medieval workman—at all times a subject of the greatest interest—has led him to introduce features which were not in his originals, or details which he could not possibly have seen. -

Master at Arms Regulations

Master-at-Arms Regulations Version 4 Master- at- Arms Regulations Version 4.0 - Autumn 2015 1 Master-at-Arms Regulations Version 4 Contents 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Definitions 3 2. Code of Law 4 2.1 Weapons and the Law 5 3. MaA Kit Specifications 6 4. MaA Kit Checks 7 4.1 Disputes 7 4.2 Master at Arms Checks at Local Events 7 5. General Rules for Kit 8 6. Mandatory Rulings for All Weapons 9 7. Individual Weapons Guidelines 11 7.1 Seaxes and Double Edged Fighting Knives 11 7.2 Swords 14 7.3 Axes 16 7.4 Broad Axes 17 7.5 Maces 18 7.6 Spears 20 7.7 Agricultural Implements 22 8. Armour Guidelines 23 8.1 General Guidelines 23 8.2 Mail Shirts and Metal Armour 23 8.3 Leather, Cloth and Padded Armour 26 8.4 Limb Armour 28 8.5 Head Protection 29 8.6 Shield Guidelines 31 8.6.1 Round Shields 32 8.6.2 Shield Designs 33 8.6.3 Long (Kite) Shields 35 8.6.4 Long Shield Designs 35 9. Warriors 37 10. Battlefield Authentic 38 Appendix 1: Some Notes on Spring Steel 39 Bending Test 39 Notch Hardness (Strike) Test 39 Weapons at a Glance 40 Appendix 2: How To Fit a Spear Head 41 The intellectual property of this document is vested in Regia Anglorum. The whole or parts may be reproduced by paid-up members of the Society for onward trans-mission to other members of Regia Anglorum for use in the context of a set of regulations. -

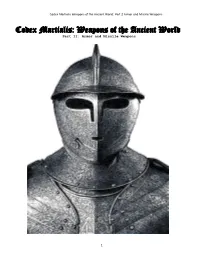

Codex Martialis: Weapons of the Ancient World

Cod ex Mart ial is Weapo ns o f t he An cie nt Wor ld : Par t 2 Arm or a nd M issile Weapo ns Codex Martialis : Weapons of the A ncient World Par t II : Ar mo r an d Mi ss il e We ap on s 1 188.6.65.233 Cod ex Mart ial is Weapo ns o f t he An cie nt Wor ld : Par t 2 Arm or a nd M issile Weapo ns Codex Martialis: Weapons of the Ancient World Part 2 , Ar mor an d Missile Weapo ns Versi on 1 .6 4 Codex Ma rtia lis Copyr ig ht 2 00 8, 2 0 09 , 20 1 0, 2 01 1, 20 1 2,20 13 J ean He nri Cha nd ler 0Credits Codex Ma rtia lis W eapons of th e An ci ent Wo rld : Jean He nri Chandler Art ists: Jean He nri Cha nd ler , Reyna rd R ochon , Ram on Esteve z Proofr ead ers: Mi chael Cur l Special Thanks to: Fabri ce C og not of De Tail le et d 'Esto c for ad vice , suppor t and sporad ic fa ct-che cki ng Ian P lum b for h osting th e Co de x Martia lis we bsite an d co n tinu in g to prov id e a dvice an d suppo rt wit ho ut which I nev e r w oul d have publish ed anyt hi ng i ndepe nd ent ly. -

Examination and Assessment of the Wenceslaus Mail Hauberk

KOMUNIKATY – ANNOUNCEMENTS Acta Militaria Mediaevalia VIII Kraków – Rzeszów – Sanok 2012, s. 229-242 Nicholas Checksfield David Edge Alan Williams EXAMINATION AND ASSESSMENT OF THE WENCESLAUS MAIL HAUBERK Abstract: N. Checksfield, D. Edge, A. Williams 2012, Examination and assessment of the Wenceslaus mail hauberk, AMM VIII: 229-242 The mail shirt kept in Prague Castle which is said to have belonged to Sv. Vaclav (Saint Wenceslaus) has been examined to assess the methods used in its construction. The use of “tailoring” (alterations in the number of links attached to each link in order to alter the shape of the shirt) is discussed, as well as the presence of repairs. A number of features of its construction appear to suggest an earlier rather than a later date. Key words: Mail shirt, riveted links, welded links, mail tailoring, hauberk, ventail, hood, standard The Mail Coat and affixed to a polypropylene supporting mesh In 2011 small group of armour curators and (Fig. 3). It was not possible to remove the garment conservators from the Wallace Collection in London from its support, since it was comprehensively travelled to Prague at the invitation of the Castle tied down onto it with a fine clear nylon filament authorities to view and assess the Wenceslaus mail (Fig. 4). This method of securing loose rings and coat. The Wallace Collection had organised an rendering the coat as stable as possible for both exhibition (We’ve Got Mail) on the origins and movement and display was an extremely effective construction of historic mail armour only the year solution to a serious problem, given the age and before, so all those involved were particularly fragility of the piece; however, it did have the absorbed and interested in the subject, and especially disadvantage that once the mail had been secured excited to be granted the privilege of viewing and onto its support it was very difficult to assess handling such an important historic garment out of the ‘flow’ of the material and the more subtle its display case.