The Introduction and Development of Plate Armour in Medieval Western Europe C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIEVAL ARMOR Over Time

The development of MEDIEVAL ARMOR over time WORCESTER ART MUSEUM ARMS & ARMOR PRESENTATION SLIDE 2 The Arms & Armor Collection Mr. Higgins, 1914.146 In 2014, the Worcester Art Museum acquired the John Woodman Higgins Collection of Arms and Armor, the second largest collection of its kind in the United States. John Woodman Higgins was a Worcester-born industrialist who owned Worcester Pressed Steel. He purchased objects for the collection between the 1920s and 1950s. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 3 Introduction to Armor 1994.300 This German engraving on paper from the 1500s shows the classic image of a knight fully dressed in a suit of armor. Literature from the Middle Ages (or “Medieval,” i.e., the 5th through 15th centuries) was full of stories featuring knights—like those of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, or the popular tale of Saint George who slayed a dragon to rescue a princess. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 4 Introduction to Armor However, knights of the early Middle Ages did not wear full suits of armor. Those suits, along with romantic ideas and images of knights, developed over time. The image on the left, painted in the mid 1300s, shows Saint George the dragon slayer wearing only some pieces of armor. The carving on the right, created around 1485, shows Saint George wearing a full suit of armor. 1927.19.4 2014.1 WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 5 Mail Armor 2014.842.2 The first type of armor worn to protect soldiers was mail armor, commonly known as chainmail. -

Weaponry & Armor

Weaponry & Armor “Imagine walking five hundred miles over the course of two weeks, carrying an arquebus, a bardiche, a stone of grain, another stone of water, ten pounds of shot, your own armor, your tent, whatever amenities you want for yourself, and your lord’s favorite dog. In the rain. In winter. With dysentery. Alright, are you imagining that? Now imagine that as soon as you’re done with that, you need to actually fight the enemy. You have a horse, but a Senator’s nephew is riding it. You’re knee-deep in mud, and you’ve just been assigned a rookie to train. He speaks four languages, none of which are yours, and has something to prove. Now he’s drunk and arguing with your superiors, you haven’t slept in thirty hours, you’ve just discovered that the fop has broken your horse’s leg in a gopher hole, and your gun’s wheellock is broken, when just then out of the dark comes the beating of war-drums. Someone screams, and a cannonball lands in your cooking fire, where you were drying your boots. “Welcome to war. Enjoy your stay.” -Mago Straddock Dacian Volkodav You’re probably going to see a lot of combat in Song of Swords, and you’re going to want to be ready for it. This section includes everything you need to know about weapons, armor, and the cost of carrying them to battle. That includes fatigue and encumbrance. When you kit up, remember that you don’t have to wear all of your armor all of the time, nor do you need to carry everything physically on your person. -

Stab Resistant Body Armour

IAN HORSFALL STAB RESISTANT BODY ARMOUR COLLEGE OF DEFENCE TECHNOLOGY SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF PhD CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY ENGINEERING SYSTEMS DEPARTMENT SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF PhD 1999-2000 IAN HORSFALL STAB RESISTANT BODY ARMOUR SUPERVISOR DR M. R. EDWARDS MARCH 2000 ©Cranfield University, 2000. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT There is now a widely accepted need for stab resistant body armour for the police in the UK. However, very little research has been done on knife resistant systems and the penetration mechanics of sharp projectiles are poorly understood. This thesis explores the general background to knife attack and defence with a particular emphasis on the penetration mechanics of edged weapons. The energy and velocity that can be achieved in stabbing actions has been determined for a number of sample populations. The energy dissipated against the target was shown to be primarily the combined kinetic energy of the knife and the arm of the attacker. The compliance between the hand and the knife was shown to significantly affect the pattern of energy delivery. Flexibility and the resulting compliance of the armour was shown to have a significant effect upon the absorption of this kinetic energy. The ability of a knife to penetrate a variety of targets was studied using an instrumented drop tower. It was found that the penetration process consisted of three stages, indentation, perforation and further penetration as the knife slides through the target. Analysis of the indentation process shows that for slimmer indenters, as represented by knives, frictional forces dominate, and indentation depth becomes dependent upon the coefficient of friction between indenter and sample. -

From Knights' Armour to Smart Work Clothes

September 16, 2020 Suits of steel: from knights’ armour to smart work clothes From traditional metal buttons to futuristic military exoskeletons, which came to the real world from the pages of comics. From the brigandines of medieval dandies to modern fire-resistant clothing for hot work areas. Steel suits have come a long way, and despite a brief retreat caused by a “firearm”, they are again conquering the battlefields and becoming widely used in cutting-edge operations. Ancestors of skins and cotton wool The first armour that existed covered the backs of warriors. For the Germanic tribes who attacked the Roman Empire, it was not considered shameful to escape battle. They protected their chests by dodging, while covering their backs, which became vulnerable when fleeing, with thick animal skins over the shoulders. Soldiers of ancient Egypt and Greece wore multi-layer glued and quilted clothes as armour. Mexican Aztecs faced the conquistadors in quilted wadded coats a couple of fingers thick. In turn, the Spanish borrowed the idea from the Mexicans. In medieval Europe, such protective clothing was widely used up to the 16th century. The famous Caucasian felt cloak also began life as armour. Made of wool using felting technology, it was invulnerable against steel sabres , arrows and even some types of bullets. Metal armour: milestones Another ancient idea for protective clothing was borrowed from animals. The scaled skin of pangolins was widely used as armour by Indian noble warriors, the Rajputs. They began to replicate a scaly body made of copper back in ancient Mesopotamia, then they began to use brass and later steel. -

![Educational Charts. [Arms and Armor]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4584/educational-charts-arms-and-armor-264584.webp)

Educational Charts. [Arms and Armor]

u UC-NRLF 800 *B ST 1S1 CO CO Q n . OPOIIT, OF ART EDUCATIONAL G E A H I S Table of Contents: 1 Periods, of armor, 2 Suit of armor: pts. named. Evolution of 3 Helmets. 4 Breastplates. 5 Gauntlets. 6 Shields. 7 Swords. 8 Pole Arms. 9 Guns,. 10 Crossbows. 11 Spurs. 12 Photos s h ov; i ?: how a helmet is ma d e ft 4- HALF ARMOR COMPLETE ARMOR LATE XVI CENTURY COMPLETE ARMOR XVI CENTURY MAXIMILIAN TRANSITIONAL MAIL AND PLATE EUROPEAN ARMOR AND ITS DEVELOPMENT DURING A THOUSAND YEARS FROM A.D. 650 TO 165O 650 MASHIKE MURAYAMft.DCI.. 366451 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/educationalchartOOmetrrich S u BOWL or SKULL, timbre, scheitelstuck, COPPO, CALVA JUGULAR. JUCULAIRE. BACKENSTUCK. JUGULARE. YUGULAR VENTAIL, VENTAIL. SCHEMBART, VENTACL10 VENTALLE. [UPPER PART BECOMES VISOR] BEVOR, MENTONNIERE, KINREFF, BAVIERA, BARBOTE RONDEL, RONDELLE. SCHEIBE, ROTELLINO, LUNETA GORGET. GORGERIN, KRAGEN, GOLETTA, GORJAL NECK-GUARD garde-col, brech- RANDER, GUARDA-GOLETTA, BUFETA . PAULDRON, EPAULIERE, ACHSEL. I SPALL ACCIO, GUARDABRAZO / _ 11^4 LANCE -REST, faucre. rust- HAKEN, RESTA, RESTA DE MUELLE REREBRACE, arrie re- bras. OBERARMZEUG, BRACCIALE. BRAZAL BREASTPLATE, plas- tron. BRUST, PETTO, PETO /o^ - ELBOW-COP. CUBIT1ERE. ARMKACHEL. CUBITIERA, CODAL '' BACKPLATE. dossi- ERE. RUCKEN, SCHIENA, DOS VAMBRACE. avant- BRAS. UNTERARMROHR, BRACCIALE, BRAZAL GAUNTLET, gantelet, hand- SCHUH, GANTLET, MANOPLA LOIN-GUARD GARDE- ' REINS. GESASSREIFEN, FALDA FALDAR 'TACES BRACCONIERE, BAUCH- REIFEN. PANZIERA. FALDAR TASSET. TASSETTE, BEINTASCHEN, FIANCALE. ESCARCELA - ' FALD. BRAYETTE. STAHLMACHENUN TERSHUTZ. BRAGHETTA. BRAGADURA CUISHE. CUISSARD, DIECHLINGE, COS- CIALE, OUIJOTES KNEE-COP. -

Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries

Roman Armour Chain Mail Armour Transitional Armour Plate Mail Armour Milanese Armour Gothic Armour Maximilian Armour Greenwich Armour Armour Diagrams Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Replaced old chain mail armour. Made up of dozens of small metal plates, and held together by leather laces. Lorica Segmentata Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers as protection for the lower legs and knees. Attached to legs by leather straps. Roman Greaves Page 1 ?BC - 400AD Used by Roman Legionaries. Handle is located behind the metal boss, which is in the centre of the shield. The boss protected the legionaries hand. Made from several wooden planks stuck together. Could be red or blue. Roman Shield Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Includes cheek pieces and neck protection. Iron helmet replaced old bronze helmet. Plume made of Hoarse hair. Roman Helmet Page 1 100AD - 400AD Soldier on left is wearing old chain mail and bronze helmet. Soldiers on right wear newer iron helmets and Lorica Segmentata. All soldiers carry shields and gladias’. Roman Legionaries Page 1 400BC - 400AD Used as primary weapon by most Roman soldiers. Was used as a thrusting weapon rather than a slashing weapon Roman Gladias Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers. Decorations depict muscles of the body. Made out of a single sheet of metal, and beaten while still hot into shape Roman Cuiruss Page 1 ?- 400AD Chain Mail Armour Page 2 400BC - 1600AD Worn by Vikings, Normans, Saxons and most other West European civilizations of the time. -

Constructing a Heavy-List Gambeson Tips and Techniques

Constructing a Heavy-List Gambeson Tips and Techniques Lady Magdalena von Regensburg mka Marla Berry [email protected] July 16, 2005 An Historic Overview “Mail is tough but flexible; it resists a cutting sword-stroke but needs a padded or quilted undergarment as a shock absorber against a heavy blow.”1 Quilted garments were part of soldiers’ kits in varying forms and with varying names throughout most of the SCA timeline. As early as the late Roman/early Byzantine period there is documentation for quilted or padded coats called Zabai or Kabadia.2 Illuminations from Maciejowski Bible (circa 1250) show aketons or gambesons. “These terms seem to have been interchangeable but the weight of evidence From “Jonathan and his Armor- suggests that ‘aketon’ refers to garments worn under the mail while bearer Attack the Philistines,” gambesons were worn over or instead of it...The gambeson is often from the Maciejowski Bible, referred to in contemporary accounts as being worn by the common circa 1250. soldiery and, indeed, is part of the equipment required by the Assize of Arms of 1185 of Edward I of England.”3 Extant examples from the fourteenth century include the pourpoint of Charles de Blois (d. 1364) and the late fourteenth century jupon of Charles VI. Fifteenth century documents mention arming doublets and padded jacks. These garments were worn under maille, over maille, under plate, over plate, or on their own. Some were designed to encase maille or plate. “Infantry, as laid down in the Assize of Arms of 1182, often wore one of two types of gambeson. -

Semi-Historical Arms and Armor the Following Are Some Notes About The

Semi-Historical Arms and Armor The following are some notes about the weapons and armor tables in D&D 5th edition, as they pertain to their relationship to modern understandings of historical arms and armor. In general, 5th edition is far more accurate to ancient and medieval sources regarding these topics than prior editions, but for the sake of balance and ease of play without the onerous restrictions of reality, there are still some expected incongruences. This article attempts to explain some particular facets about the use of arms and armor throughout our long, shared history, and to offer some suggestions (imbalanced as they may be) on how such items would have been used in particular times and places. A note on generalities: One of the best things 5th edition offers in these tables is the generalization of particular weapons and armor compared to prior editions. Is there a significant, functional difference between a half-sword, arming sword, backsword, wakizashi, tulwar, or any other various forms of predominately one-handed pokey and slashy things with 13 inch, sometimes 14 or 20 or even 30 inch blades? Well, actually yes, but that level of discrimination is often not noticeable in the granularity of the combat mechanics of most systems, and, more importantly, how modern readers often distinguish them is often anachronistic. For instance, almost all straight sword-like weapons, be it arming swords, half-swords, back swords, longswords or even great swords like claymores (but not Messers!) are referred to in ancient and medieval texts (MS I.33, Liberi, etc) as… swords. -

The Terminology of Armor in Old French

1 A 1 e n-MlS|^^^PP?; The Terminology Of Amor In Old French. THE TERMINOLOGY OF ARMOR IN OLD FRENCH BY OTHO WILLIAM ALLEN A. B. University of Illinois, 1915 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ROMANCE LANGUAGES IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1916 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL CO oo ]J1^J % I 9 I ^ I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPER- VISION BY WtMc^j I^M^. „ ENTITLED ^h... *If?&3!£^^^ ^1 ^^Sh^o-^/ o>h, "^Y^t^C^/ BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF. hu^Ur /] CUjfo In Charge of Thesis 1 Head of Department Recommendation concurred in :* Committee on Final Examination* Required for doctor's degree but not for master's. .343139 LHUC CONTENTS Bibliography i Introduction 1 Glossary 8 Corrigenda — 79 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 http://archive.org/details/terminologyofarmOOalle i BIBLIOGRAPHY I. Descriptive Works on Armor: Boeheim, Wendelin. Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Leipzig, 1890, Quicherat, J, Histoire du costume en France, Paris, 1875* Schultz, Alwin. Das hofische Leben zur Zeit der Minnesinger. Two volumes. Leipzig, 1889. Demmin, August. Die Kriegswaffen in ihren geschicht lichen Ent wicklungen von den altesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Vierte Auflage. Leipzig, 1893. Ffoulkes, Charles. Armour and Weapons. Oxford, 1909. Gautier, Leon. La Chevalerie. Viollet-le-Duc • Dictionnaire raisonne' du mobilier frangais. Six volumes. Paris, 1874. Volumes V and VI. Ashdown, Charles Henry. Arms and Armour. New York. Ffoulkes, Charles. The Armourer and his Craft. -

Plate Armor (Edited from Wikipedia)

Plate Armor (Edited from Wikipedia) SUMMARY Plate armor is a historical type of personal body armor made from iron or steel plates, culminating in the iconic suit of armor entirely encasing the wearer. While there are early predecessors, full plate armor developed in Europe during the Late Middle Ages, especially in the context of the Hundred Years' War, from the coat of plates worn over mail suits during the 13th century. In Europe, plate armor reached its peak in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The full suit of armor is thus a feature of the very end of the Middle Ages and of the Renaissance period. Its popular association with the "medieval knight" is due to the specialized jousting armor which developed in the 16th century. Full suits of Gothic plate armor were worn on the battlefields of the Burgundian and Italian Wars. The most heavily armored troops of the period were heavy cavalry such as the gendarmes and early cuirassiers, but the infantry troops of the Swiss mercenaries and the landsknechts also took to wearing lighter suits of "three quarters" munition armor, leaving the lower legs unprotected. The use of plate armor declined in the 17th century, but it remained common both among the nobility and for the cuirassiers throughout the European wars of religion. After 1650, plate armor was mostly reduced to the simple breastplate (cuirass) worn by cuirassiers. This was due to the development of the flintlock musket, which could penetrate armor at a considerable distance. For infantry, the breastplate gained renewed importance with the development of shrapnel in the late Napoleonic wars. -

Heroic Armor of the Italian Renaissnace

30. MASKS GARNITURE OF CHARLES V Filippo Negroli and his brothers Milan, dated 1539 Steel, gold, and silver Wt. 31 lb. 3 oz. (14,490 g) RealArmeria, Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid (A 139) he Masks Garniture occupies a special place in the Negroli Toeuvre as the largest surviving armor ensemble signed by Filippo N egroli and the only example of his work to specify unequivocally the participation of two or more of his broth ers. The armor's appellation, "de los mascarones," derives from the grotesque masks that figure prominently in its dec oration, and it was coined by Valencia de Don Juan (1898) to distinguish it from the many other harnesses of Charles V in the Real Armeria. Indeed, for Valencia, none of the emperor's numerous richly embellished armors could match this one for the beauty of its decoration. As the term "garniture" implies, the harness possesses a number of exchange and reinforcing pieces that allow it to be employed, with several variations, for mounted use in the field as well as on foot. The exhibited harness is composed of the following ele ments: a burgonet with hinged cheekpieces and a separate, detachable buffe to close the face opening; a breastplate with two downward-overlapping waist lames and a single skirt lame supporting tassets (upper thigh defenses) of seven lames each that are divisible between the second and third lames; a backplate with two waist lames and a single culet (rump) lame; asymmetrical pauldrons (shoulder defenses) made in one with vambraces (arm defenses) and having large couters open on the inside of the elbows; articulated cuisses (lower thigh defenses) with poleyns (knees); and half greaves open on the inside of the leg. -

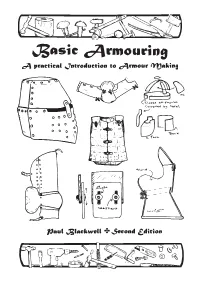

Armour Manual Mark II Ze

Basic Armouring—A Practical Introduction to Armour Making, Second Edition By Paul Blackwell Publishing History March 1986: First Edition March 2002: Second Edition Copyright © 2002 Paul Blackwell. This document may be copied and printed for personal use. It may not be distributed for profit in whole or part, or modified in any way. Electronic copies may be made for personal use. Electronic copies may not be published. The right of Paul Blackwell to be identified as the Author and Illustrator of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The latest electronic version of this book may be obtained from: http://www.brighthelm.org/ Ye Small Print—Cautionary Note and Disclaimer Combat re-enactment in any form carries an element of risk (hey they used to do this for real!) Even making armour can be hazardous, if you drop a hammer on your foot, cut yourself on a sharp piece of metal or do something even more disastrous! It must be pointed out, therefore, that if you partake in silly hobbies such as these you do so at your own risk! The advice and information in this booklet is given in good faith (most having been tried out by the author) however as I have no control over what you do, or how you do it, I can accept no liability for injury suffered by yourself or others while making or using armour. Ye Nice Note Having said all that I’ll just add that I’ve been playing for ages and am still in one piece and having fun.