Plate Armor (Edited from Wikipedia)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIEVAL ARMOR Over Time

The development of MEDIEVAL ARMOR over time WORCESTER ART MUSEUM ARMS & ARMOR PRESENTATION SLIDE 2 The Arms & Armor Collection Mr. Higgins, 1914.146 In 2014, the Worcester Art Museum acquired the John Woodman Higgins Collection of Arms and Armor, the second largest collection of its kind in the United States. John Woodman Higgins was a Worcester-born industrialist who owned Worcester Pressed Steel. He purchased objects for the collection between the 1920s and 1950s. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 3 Introduction to Armor 1994.300 This German engraving on paper from the 1500s shows the classic image of a knight fully dressed in a suit of armor. Literature from the Middle Ages (or “Medieval,” i.e., the 5th through 15th centuries) was full of stories featuring knights—like those of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, or the popular tale of Saint George who slayed a dragon to rescue a princess. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 4 Introduction to Armor However, knights of the early Middle Ages did not wear full suits of armor. Those suits, along with romantic ideas and images of knights, developed over time. The image on the left, painted in the mid 1300s, shows Saint George the dragon slayer wearing only some pieces of armor. The carving on the right, created around 1485, shows Saint George wearing a full suit of armor. 1927.19.4 2014.1 WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 5 Mail Armor 2014.842.2 The first type of armor worn to protect soldiers was mail armor, commonly known as chainmail. -

From Knights' Armour to Smart Work Clothes

September 16, 2020 Suits of steel: from knights’ armour to smart work clothes From traditional metal buttons to futuristic military exoskeletons, which came to the real world from the pages of comics. From the brigandines of medieval dandies to modern fire-resistant clothing for hot work areas. Steel suits have come a long way, and despite a brief retreat caused by a “firearm”, they are again conquering the battlefields and becoming widely used in cutting-edge operations. Ancestors of skins and cotton wool The first armour that existed covered the backs of warriors. For the Germanic tribes who attacked the Roman Empire, it was not considered shameful to escape battle. They protected their chests by dodging, while covering their backs, which became vulnerable when fleeing, with thick animal skins over the shoulders. Soldiers of ancient Egypt and Greece wore multi-layer glued and quilted clothes as armour. Mexican Aztecs faced the conquistadors in quilted wadded coats a couple of fingers thick. In turn, the Spanish borrowed the idea from the Mexicans. In medieval Europe, such protective clothing was widely used up to the 16th century. The famous Caucasian felt cloak also began life as armour. Made of wool using felting technology, it was invulnerable against steel sabres , arrows and even some types of bullets. Metal armour: milestones Another ancient idea for protective clothing was borrowed from animals. The scaled skin of pangolins was widely used as armour by Indian noble warriors, the Rajputs. They began to replicate a scaly body made of copper back in ancient Mesopotamia, then they began to use brass and later steel. -

Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries

Roman Armour Chain Mail Armour Transitional Armour Plate Mail Armour Milanese Armour Gothic Armour Maximilian Armour Greenwich Armour Armour Diagrams Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Replaced old chain mail armour. Made up of dozens of small metal plates, and held together by leather laces. Lorica Segmentata Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers as protection for the lower legs and knees. Attached to legs by leather straps. Roman Greaves Page 1 ?BC - 400AD Used by Roman Legionaries. Handle is located behind the metal boss, which is in the centre of the shield. The boss protected the legionaries hand. Made from several wooden planks stuck together. Could be red or blue. Roman Shield Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Includes cheek pieces and neck protection. Iron helmet replaced old bronze helmet. Plume made of Hoarse hair. Roman Helmet Page 1 100AD - 400AD Soldier on left is wearing old chain mail and bronze helmet. Soldiers on right wear newer iron helmets and Lorica Segmentata. All soldiers carry shields and gladias’. Roman Legionaries Page 1 400BC - 400AD Used as primary weapon by most Roman soldiers. Was used as a thrusting weapon rather than a slashing weapon Roman Gladias Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers. Decorations depict muscles of the body. Made out of a single sheet of metal, and beaten while still hot into shape Roman Cuiruss Page 1 ?- 400AD Chain Mail Armour Page 2 400BC - 1600AD Worn by Vikings, Normans, Saxons and most other West European civilizations of the time. -

The Terminology of Armor in Old French

1 A 1 e n-MlS|^^^PP?; The Terminology Of Amor In Old French. THE TERMINOLOGY OF ARMOR IN OLD FRENCH BY OTHO WILLIAM ALLEN A. B. University of Illinois, 1915 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ROMANCE LANGUAGES IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1916 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL CO oo ]J1^J % I 9 I ^ I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPER- VISION BY WtMc^j I^M^. „ ENTITLED ^h... *If?&3!£^^^ ^1 ^^Sh^o-^/ o>h, "^Y^t^C^/ BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF. hu^Ur /] CUjfo In Charge of Thesis 1 Head of Department Recommendation concurred in :* Committee on Final Examination* Required for doctor's degree but not for master's. .343139 LHUC CONTENTS Bibliography i Introduction 1 Glossary 8 Corrigenda — 79 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 http://archive.org/details/terminologyofarmOOalle i BIBLIOGRAPHY I. Descriptive Works on Armor: Boeheim, Wendelin. Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Leipzig, 1890, Quicherat, J, Histoire du costume en France, Paris, 1875* Schultz, Alwin. Das hofische Leben zur Zeit der Minnesinger. Two volumes. Leipzig, 1889. Demmin, August. Die Kriegswaffen in ihren geschicht lichen Ent wicklungen von den altesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Vierte Auflage. Leipzig, 1893. Ffoulkes, Charles. Armour and Weapons. Oxford, 1909. Gautier, Leon. La Chevalerie. Viollet-le-Duc • Dictionnaire raisonne' du mobilier frangais. Six volumes. Paris, 1874. Volumes V and VI. Ashdown, Charles Henry. Arms and Armour. New York. Ffoulkes, Charles. The Armourer and his Craft. -

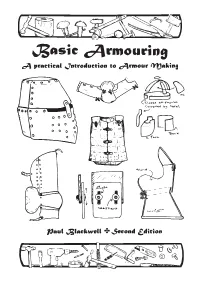

Armour Manual Mark II Ze

Basic Armouring—A Practical Introduction to Armour Making, Second Edition By Paul Blackwell Publishing History March 1986: First Edition March 2002: Second Edition Copyright © 2002 Paul Blackwell. This document may be copied and printed for personal use. It may not be distributed for profit in whole or part, or modified in any way. Electronic copies may be made for personal use. Electronic copies may not be published. The right of Paul Blackwell to be identified as the Author and Illustrator of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The latest electronic version of this book may be obtained from: http://www.brighthelm.org/ Ye Small Print—Cautionary Note and Disclaimer Combat re-enactment in any form carries an element of risk (hey they used to do this for real!) Even making armour can be hazardous, if you drop a hammer on your foot, cut yourself on a sharp piece of metal or do something even more disastrous! It must be pointed out, therefore, that if you partake in silly hobbies such as these you do so at your own risk! The advice and information in this booklet is given in good faith (most having been tried out by the author) however as I have no control over what you do, or how you do it, I can accept no liability for injury suffered by yourself or others while making or using armour. Ye Nice Note Having said all that I’ll just add that I’ve been playing for ages and am still in one piece and having fun. -

Military Technology in the 12Th Century

Zurich Model United Nations MILITARY TECHNOLOGY IN THE 12TH CENTURY The following list is a compilation of various sources and is meant as a refer- ence guide. It does not need to be read entirely before the conference. The breakdown of centralized states after the fall of the Roman empire led a number of groups in Europe turning to large-scale pillaging as their primary source of income. Most notably the Vikings and Mongols. As these groups were usually small and needed to move fast, building fortifications was the most efficient way to provide refuge and protection. Leading to virtually all large cities having city walls. The fortifications evolved over the course of the middle ages and with it, the battle techniques and technology used to defend or siege heavy forts and castles. Designers of castles focused a lot on defending entrances and protecting gates with drawbridges, portcullises and barbicans as these were the usual week spots. A detailed ref- erence guide of various technologies and strategies is compiled on the following pages. Dur- ing the third crusade and before the invention of gunpowder the advantages and the balance of power and logistics usually favoured the defender. Another major advancement and change since the Roman empire was the invention of the stirrup around 600 A.D. (although wide use is only mentioned around 900 A.D.). The stirrup enabled armoured knights to ride war horses, creating a nearly unstoppable heavy cavalry for peasant draftees and lightly armoured foot soldiers. With the increased usage of heavy cav- alry, pike infantry became essential to the medieval army. -

The Evolution of Plate Armor in Medieval Europe and Its Relation to Contemporary Weapons Development

History, Department of History Theses University of Puget Sound Year 2016 Clad In Steel: The Evolution of Plate Armor in Medieval Europe and its Relation to Contemporary Weapons Development Jason Gill [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/history theses/21 Clad in Steel: The Evolution of Plate Armor in Medieval Europe and its Relation to Contemporary Arms Development Jason Gill History 400 Professor Douglas Sackman 1 When thinking of the Middle Ages, one of the first things that comes to mind for many is the image of the knight clad head to toe in a suit of gleaming steel plate. Indeed, the legendary plate armor worn by knights has become largely inseparable from their image and has inspired many tales throughout the centuries. But this armor was not always worn, and in fact for most of the years during which knights were a dominant force on battlefields plate was a rare sight. And no wonder, for the skill and resources which went into producing such magnificent suits of armor are difficult to comprehend. That said, it is only rarely throughout history that soldiers have gone into battle without any sort of armor, for in the chaotic environment of battle such equipment was often all that stood between a soldier and death. Thus, the history of both armor and weapons is essential to a fuller understanding of the history of war. In light of this importance, it is remarkable how little work has been done on charting the history of soldiers’ equipment in the Middle Ages. -

For BUHURT CATEGORIES Rules for BUHURT CATEGORIES

Historical Medieval Battle International Association Rules for BUHURT CATEGORIES Rules for BUHURT CATEGORIES GENERAL REGULATIONS 1.1 Historical Medieval Battle (HMB) is full contact sporting combat in which historical protective and offensive arms of the Middle Ages – made especially and adjusted to suit this kind of competition – are used. HMBs are held in the lists of standardized dimensions, with different types of authentic weapons, depending on the kind of a battle. The concept of HMB includes all kinds of full contact combat with the use of items of Historical Reenactment of the Middle Ages (HRMA), namely historical fencing, buhurts, melee, duels, small group battles, mass field battles, professional fights, etc. HMBs are always held in full contact, but are represented by different categories with various authorized and prohibited techniques. In addition, victory conditions, battle regulations, tournament schemes and other parameters are different. 1.2 All HMBs are held under control and observation of a marshal’s (referee’s) group, including one knight marshal (main referee), field referees, linesmen and referees monitoring the video coverage and authenticity master. The number of members of the marshal’s group is established separately for each event, depending on its format and content. The presence of the knight marshal and field referees is required in every type of combat. The presence of a member of authenticity committee is strongly recommended. 1.2.1. The knighvt marshal is selected by the event organizers. In case of any disagreement the knight marshal’s decision is final. 1.2.2. The records of the combat process and combat results are made by the secretariat. -

Selection and Application Guide to Personal Body Armor NIJ Guide 100–01 (Update to NIJ Guide 100–98) U.S

NOTICE Portions of this guide have been superseded by NCJ 247281, Selection and Application Guide to Ballistic-Resistant Body Armor For Law Enforcement, Corrections and Public Safety: NIJ Selection and Application Guide-0101.06. This new resource supersedes the portions of NIJ Guide 100-01 (NCJ 189633) that deal with ballistic-resistant armor. It does not supersede those portions that deal with stab-resistant armor. A separate guide on stab-resistant armor will be published when NIJ Standard-0115.00, Stab Resistance of Personal Body Armor (NCJ 183652), is updated. U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice Selection and Application Guide to Personal Body Armor NIJ Guide 100–01 (Update to NIJ Guide 100–98) U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street N.W. Washington, DC 20531 John Ashcroft Attorney General Deborah J. Daniels Assistant Attorney General Sarah V. Hart Director, National Institute of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice World Wide Web Site World Wide Web Site http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice Selection and Application Guide to Personal Body Armor NIJ Guide 100–01 (Replaces Selection and Application Guide to Police Body Armor, NIJ Guide 100–98) November 2001 Published by: The National Institute of Justice’s National Law Enforcement and Corrections Technology Center Lance Miller, Testing Manager P.O. Box 1160, Rockville, MD 20849–1160 800–248–2742; 301–519–5060 NCJ 189633 National Institute of Justice Sarah V. -

Knllhtsj^ARMOR

School Picture Sei Number 10 KNllHTSj^ARMOR THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART KNIGHTS IN ARMOR The knight was a warrior on horseback. He and his men had to fight for their liege lord when ever their services were demanded. In return the knight received a grant of land or special privi leges to provide for the cost of his armor, the care of his horse, and the upkeep of his household and retinue. He was considered a member of the nobility and obeyed the code of ethics which we call chivalry. Thus a knight should be loyal, courageous, and courteous as well as skilled in all the arts of war. His obligations to his lord and his own sense of honor brought him into many conflicts. He fought in major wars and countless minor ones. As a Crusader he "took the cross" and journeyed to the Holy Land to fight the infidels. As a champion of the wronged or to settle a point of honor, he challenged another knight in single combat. In quest of adventure he wandered about strange lands as a knight errant. When times were peace ful, he kept in training by fighting in jousts and tournaments. In these enclosed pictures you will see the vari ous activities of the knight, as well as some of his weapons and the armor that provided the pro tection he needed. THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART 1. NORMAN CONQUEST Detail, Bayeux embroidery French, Late 11th Century Bayeux THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART In the time of William the Conqueror, knights seem to have worn armor of rings sewed on heavily padded garments, conical helmets, and carried javelins, swords, and kite-shaped shields. -

The Classic Suit of Armor

Project Number: JLS 0048 The Classic Suit of Armor An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by _________________ Justin Mattern _________________ Gregory Labonte _________________ Christopher Parker _________________ William Aust _________________ Katrina Van de Berg Date: March 3, 2005 Approved By: ______________________ Jeffery L. Forgeng, Advisor 1 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................. 5 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 6 RESEARCH ON ARMOR: ......................................................................................................................... 9 ARMOR MANUFACTURING ......................................................................................................................... 9 Armor and the Context of Production ................................................................................................... 9 Metallurgy ........................................................................................................................................... 12 Shaping Techniques ............................................................................................................................ 15 Armor Decoration -

From Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Medieval Romance from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight RL 1 Cite textual evidence Romance by the Gawain Poet Translated by John Gardner to support inferences drawn KEYWORD: HML12-228 from the text. RL 3 Analyze VIDEO TRAILER the impact of the author’s choices regarding how to develop and relate elements of a story. RL 5 Analyze how Meet the Author an author’s choices concerning how to structure specific parts of a text contribute to its includes a dozen rough illustrations of overall structure. SL 1c Propel the four poems, though it is impossible conversations by responding to questions that probe reasoning to verify who created the images for this and evidence. L 2b Spell correctly. manuscript. Because Pearl is the most technically brilliant of the four poems, the did you know? Gawain Poet is sometimes also called the Pearl Poet. • The first modern edition of Sir Gawain A Man for All Seasons The Gawain and the Green Knight Poet’s works reveal that he was widely was translated by read in French and Latin and had some J. R. R. Tolkien, a respected scholar of knowledge of law and theology. Although Old and Middle he was familiar with many details of English as well as the medieval aristocratic life, his descriptions author of The Lord of The Gawain Poet’s rich imagination and metaphors also show a love of the the Rings. and skill with language have earned him countryside and rural life. recognition as one of the greatest medieval The Ideal Knight In the person of Sir English poets.