Digital Geologic Map and Geochronologic, Geochemical and Geothermal Database of the South-Eastern Part of the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexicoi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting

Program Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting June 12–14, 2018 • Knoxville, Tennessee Institutional Support Lunar and Planetary Institute Universities Space Research Association Convener Devon Burr Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Science Organizing Committee David Williams, Chair Arizona State University Devon Burr Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Robert Jacobsen Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Bradley Thomson Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Abstracts for this meeting are available via the meeting website at https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/pgm2018/ Abstracts can be cited as Author A. B. and Author C. D. (2018) Title of abstract. In Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting, Abstract #XXXX. LPI Contribution No. 2066, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. Guide to Sessions Tuesday, June 12, 2018 9:00 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Introduction and Mercury and Venus Maps 1:00 p.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Mars Maps 5:30 p.m. Strong Hall Poster Area Poster Session: 2018 Planetary Geologic Mappers Meeting Wednesday, June 13, 2018 8:30 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room GIS and Planetary Mapping Techniques and Lunar Maps 1:15 p.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Asteroid, Dwarf Planet, and Outer Planet Satellite Maps Thursday, June 14, 2018 8:30 a.m. Strong Hall Optional Field Trip to Appalachian Mountains Program Tuesday, June 12, 2018 INTRODUCTION AND MERCURY AND VENUS MAPS 9:00 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Chairs: David Williams Devon Burr 9:00 a.m. -

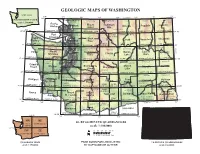

Geologic Maps of Washington

GEOLOGIC MAPS OF WASHINGTON DGER GM-53 124° 117° 123° 122° 121° 120° CANADA 119° 118° 49° 49° WASHINGTON STATE PEND DGER OFR 2000-5 WHATCOM DGER OFR 90-5 USA FERRY (scale 1:500,000) OREILLE Roche Mount Bellingham Robinson Oroville Republic Colville Harbor Baker Mtn 125° OKANOGAN DGER OFR 2003-17 48°30 USGS Map I-2660 DGER OFR 90-10 DGER OFR 90-13 48°30 CANADA DGER OFR 90-11 SAN USA Port JUAN SKAGIT DGER DGER OFR 90-12 ISLAND OFR 90-9 Cape Angeles Port Sauk Nespelem Chewelah Flattery Townsend River Twisp Omak USGS Map I-1198F DGER OFR 2003-5 DGER OFR 2003-6 DGER DGER OFR 90-14 48° USGS Map I-1198G USGS Map I -2592 OFR 95-3 DGER OFR 90-16 48° CLALLAM USGS OFR 93-233 STEVENS IDAHO SNOHOMISH DOUGLAS JEFFERSON USGS OFR 91-147 CHELAN Mount Coulee Forks Seattle Skykomish Banks Spokane Olympus River Chelan Lake Dam DGER OFR 2000-4 DGER OFR 2003-4 DGER OFR 90-17 47°30 KITSAP USGS Map I-1963 USGS Map I-1661 DGER OFR 90-6 DGER OFR 90-15 47°30 GRAYS GIS data only KING LINCOLN SPOKANE Copalis HARBOR GRANT Snoqualmie Moses Beach Shelton Tacoma Wenatchee Ritzville Rosalia MASON Pass Lake DGER OFR 2003-16 KITTITAS DGER OFR 2003-15 47° DGER OFR 87-3 USGS Map I-2538 USGS Map I-1311 DGER OFR 90-1 DGER OFR 90-2 DGER OFR 90-7 47° WHITMAN PIERCE ADAMS THURSTON Westport Chehalis Mount Priest Pullman River Centralia Yakima Connell LEWIS Rainier Rapids FRANKLIN DGER DGER OFR 87-8 DGER OFR 87-8 DGER 46°30 DGER OFR 87-11 DGER OFR 87-16 OFR 86-4 OFR 94-12 DGER OFR 94-13 DGER OFR 94-14 DGER OFR 94-6 46°30 PACIFIC GARFIELD YAKIMA DGER COLUMBIA OFR 86-3 BENTON Ilwaco WAHKIAKUM Mount Clarkston Mount Richland Walla Walla Astoria St. -

Application of Geologic Mapping and Geographic Information Systems To

APPLICATION OF GEOLOGIC MAPPING AND GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS TO DELINEATE SENSITIVE KARST AREAS FOR LAND-USE DECISIONS Jim Cichon, Alex Wood, Alan Baker and Jon Arthur Florida Geological Survey, Hydrogeology Program The Problem: The Floridan aquifer system (FAS), a thick sequence of Tertiary carbonates, is the major fresh water resource in the Florida panhandle. The expanding population of the State places an ever-growing demand on the fresh-water resources through increased land and water use. Overburden comprised of surficial aquifer sediments or intermediate confining unit (ICU) sediments may act to protect the FAS from potential contamination sources where it is present. This overburden can be several hundred feet thick where it provides variable confinement for the FAS, or it can be thin to absent in areas where carbonate units comprising the FAS are exposed at or near land surface. In areas where the overburden is thin to absent, the potential for karst terrain development is increased. Sinkholes and collapse features are more common and occur at a much Figure 1: Generalized geologic map of northwestern Florida (modified from Scott, et al. 2001). greater rate than in well-confined areas. The nature of karst terrain provides preferential flow paths for surface water to enter the underlying aquifer system, and therefore aquifer systems underlying karst terrain are at a greater risk to surface contamination potential. The Geologic Map: In Florida, areas of karst topography are associated with, but not limited to shallow and exposed carbonate rocks. The state geologic map of Florida and associated cross-sections provide this detailed lithologic information (Scott, et al, 2001). -

Observations on USGS-State Cooperative Mapping

DR.WALLACE W. HACAN Director Kentucky Geological Survey (Ret.) Observations on USGS-State Cooperative Mapping HE DICTIONARY defines the word cooper- selective based on immediate needs of our T ate to mean: to work together willingly country. A state may attract the uscs to map for a common purpose. Thus, when The in it, or accelerate mapping in progress, by United States Geological Survey and a state entrance into a cooperative program. This agency enter into a cooperative agreement, also reduces the cost to the federal govern- they have definite objectives which involve ment, and produces a base map sooner, and both state and federal agencies. The signed consequently enhances economic develop- agreements are quite simple and indicate ment in the State. the nature of the funding, who performs the Fourteen states now have complete 7.5 operations, who owns the original materials, minute topographic map coverage on a the mutual considerations, and the publica- 1:24,000 scale, most of which was done in tion of the results. cooperative programs. Last year in FY 1978, There are several types of cooperative 38 states and Puerto Rico contributed $3.5 programs: million toward the National Mapping Pro- The uses furnishes the personnel, super- -gram, .- primarily for new 7.5 minute topo- vises personnel and operations, in field graphic mapping. Some states' cooperative and ofice, reviews, approves, does cartog- mapping agreements included: raphy, and publishes. Plans and priorities are formulated mutually, and funds are High-altitude aerial photography, photo- matched. inspection, and photorevision of published 7.5 minute maps in the states of Indiana, This is the same, except by agreement the state furnishes some of the personnel and Kansas, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Virginia. -

Prototytpe Implementations of the North American Data Model

Prototype Implementations of the North American Data Model Steering Committee Data Model for a Geologic Map Database by Ronald R. Wahl, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado, USA ABSTRACT The National Geologic Map Database Project (NGMDB) of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has been working to implement the North American Data Model Steering Committee (NADMSC) data model in a number of software systems. The NGMDB has implemented a number of prototype databases using object-relational software. Additional benefits discovered from this work are: iterative changes to the underlying data model do not change the data already in place, implementation of dynamic map generation based on map unit generalizations is straight-forward, and the geologic features are not necessary referred to by the geometry of the feature. Some of the problems encountered so far are: geologic language tables to accompany the database have been difficult to develop, a list of routine queries for use with the database have been slow to evolve, and the routine importation of multiple data formats from the same GIS software has not been solved. Introduction History Since enacting of the Geologic Mapping Act (GMA) by the Congress of the United States in 1992, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has been charged with building a national geologic map database. Under the provisions of the GMA, the Congress set forth the following objectives: “The objectives of the geologic mapping program shall include-- (1) determining the Nation's geologic framework through systematic -

Topographic Maps

Topographic Maps Say Thanks to the Authors Click http://www.ck12.org/saythanks (No sign in required) To access a customizable version of this book, as well as other interactive content, visit www.ck12.org CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based collaborative model termed the FlexBook®, CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide an adaptive environment for learning, powered through the FlexBook Platform®. Copyright © 2014 CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org The names “CK-12” and “CK12” and associated logos and the terms “FlexBook®” and “FlexBook Platform®” (collectively “CK-12 Marks”) are trademarks and service marks of CK-12 Foundation and are protected by federal, state, and international laws. Any form of reproduction of this book in any format or medium, in whole or in sections must include the referral attribution link http://www.ck12.org/saythanks (placed in a visible location) in addition to the following terms. Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Com- mons from time to time (the “CC License”), which is incorporated herein by this reference. -

Geologic Map Homework

Amherst College Department of Geology INTRODUCTION TO GEOLOGIC MAPS A geologic map represents the distribution of rocks across the surface of the map area by drawing lines (“contacts”) between different rock units (commonly called “formations”) and by representing each rock unit with a different color. Typically colors and contacts of a geologic map are superimposed on a topographic base map so that the contours of the surface of the earth and the rocks underlying those contours can be studied together. (For this reason, colors used are muted so that topo lines and other information are not obscured.) A geologic map also includes a variety of geologic information regarding the attitude of the rock units (their strike and dip) and the location of folds or faults that affect the rocks. A little familiarity with the conventions used in a geologic map will allow you to use any available geologic map to get to know the geology of any new or interesting area. Your objective this week is to work with a large color copy of a geologic map of an area in Montana to become more knowledgeable about how to read geologic maps in general. For the purposes of this exercise, you may write directly on the map copy. LEARNING YOUR WAY AROUND A GEOLOGIC MAP All geologic maps include basic elements that aid the reader in using the map. These include the following important components. 1) A title that indicates the area of the map. Find the title and label it 1. What area does this geologic map cover? Where is it located? 2) A bar scale (in km in newer maps and miles in older ones) that allows you to determine distances on the map. -

Gems (Geologic Map Schema)—A Standard Format for the Digital Publication of Geologic Maps

GeMS (Geologic Map Schema)—A Standard Format for the Digital Publication of Geologic Maps Chapter 10 of Section B, U.S. Geological Survey Standards, of Book 11, Collection and Delineation of Spatial Data Techniques and Methods 11–B10 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Geologic map of the western United States and surrounding areas, extracted from the “Geologic map of North America” (Reed and others, 2005; database from Garrity and Soller, 2009). Image downloaded from the National Geologic Map Database (https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_86688.htm). GeMS (Geologic Map Schema)—A Standard Format for the Digital Publication of Geologic Maps By the U.S. Geological Survey National Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program Chapter 10 of Section B, U.S. Geological Survey Standards, of Book 11, Collection and Delineation of Spatial Data Techniques and Methods 11–B10 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2020 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Geologic Maps

GEOLOGIC MAPS PURPOSE: To be able to understand, visualize, and analyze geologic maps Geologic maps show the distribution of the various igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks at Earth’s surface in plan view. The contacts between different geologic formations and the various structures that occur in the rocks are typically superimposed upon the contour lines of topography in the map area. Geologic cross sections often appear with geologic maps. They are diagrams illustrating the distribution of geologic units in the vertical dimension along a line through the map area. They may also show the topographic profile of the land surface. Map Explanations or Keys are also found accompanying geologic maps. The formations are presented and described in chronological sequence, with the oldest unit at the bottom and the youngest unit at the top. Geologic maps make use of specific map symbols to relate important information. Illustrations of common structure symbols and fault/fold relations are on pages 2 and 3. Useful items on geologic maps: • The symbol for a geologic unit, labeled on the map and in the explanation, begins with the capitalized symbol for the geologic period (or era), followed by lowercase letters that designate the name of the formation. for example, the Ordovician Swan Peak Formation is labeled “Osp” • Contact lines on a map separate and mark the boundary between two adjacent geologic formations. • Outcrops are those places where a geologic formation is exposed at the Earth’s surface. Three factors control the width of a formation’s outcrop on a geologic map: 1) the formation’s thickness; 2) the slope of the land in the area of an outcrop; and 3) the dip angle of the beds in the formation. -

NASA's Planetary Geologic Mapping Program: Overview

NASA’s Planetary Geologic Mapping Program: Overview David A. Williams Chair, Geologic Mapping Subcommittee Mapping and Planetary Spatial Infrastructure Team ISPRS Meeting Prague July 17, 2016 INTRODUCTION • Why Planetary Geologic Mapping • Advantages of Planetary Mapping • History of Planetary Map production (USGS) • Current Organization: GEMS & MAPSIT • NASA Funding: Planetary Mapping • Current Map Production Approach & Techniques • Summary WHY PLANETARY GEOLOGIC MAPPING? “On first examining a new district [planet] nothing can appear more hopeless than the chaos of rocks [landforms]; but by recording the stratification and nature of rocks [morphology, superposition & crosscutting relations] at many points, always reasoning and predicting what will be found elsewhere, light soon begins to dawn on the district [planet], and the structure of the whole becomes more or less intelligible.” Charles Darwin, autobiography (1958) (w/paraphrasing by J.F. McCauley & J.M. Moore) “… a geological map is like a graph to a physicist: it allows one to understand many observations in a comprehensive form that would be more difficult without it.” John Guest, Principles of Extraterrestrial Geologic Mapping (1974) WHY PLANETARY GEOLOGIC MAPPING? • Geologic mapping documents main geologic units and features and their relative ages and other characteristics. These form the basis for the recognition of major resurfacing events and processes operative on planetary surfaces through time Specific accomplishments include: • 1. Documentation of the geological evolution -

(For and At) Data on Mountain Issues: the Contribution of Information

IPROMO, 5 th august 2008 Paola Carrara (IREA-CNR & LNSA-UniTo) Looking (for and at) data on mountain issues: the contribution of Information Technologies and Remote Sensing Index (main road) l Basic concepts of Information Systems: Data, information, geographic data l Geograhic Information Systems (GIS): basic concepts and evolutions l How to look for or “I do not wish to reinvent the wheel”: a Spatial Data Infrasctructure to move data around l What I’m looking: RS contribution to IT systems Materials from: l Spatial Databases, P. Rigaux, M. Scholl, A. Voisard, Morgan Kaufmann, 2002 l Principles of Geographical Information Systems, P. A. Burrough, R. A. McDonnell, 2004 l Lessons from the course of Sistemi inormativi III UniBG Ingegneria l http://www.ucgis.org University Consortium for Geographic Information Science l http://www.opengeospatial.org Open Geospatial Consortium OGC l http://education.usgs.gov/common/lessons/gis.html Education resources of USGS l http://inspire.jrc.it/reports.cfmDocument archive of INSPIRE and documents of http://www.opengeospatial.org/resource/cookbooks Data … information ... datum : element of information represented by symbols/values to be elaborated/interpreted information : any aggregation of data the meaning of which is known (besides its values) Data … information ... Classification of snow covered pixels in Valle d’Aosta (white pixels=snow; black pixels=no snow) From data to information …. 94%Knowledge 60,3% increase 2006 2007 percentage of VdA surface covered by snow = 94% percentage of VdA surface -

Base Line a Newsletter of the Map and Geography Roundtable

ISSN 0272-8532 base line a newsletter of the Map and Geography Roundtable TABLE OF CONTENTS Our Man in England 24 Ramb 1ings from the Cha ir 25 And From the Ed itor 25 Conferences •.•.......•.••..•.••.•.....•......• 26 News...••...••.•••..••..•..•.•••.•.......••... 27 On the Cataloging/Cataloguing Front .........•. 28 New Books and Maps 33 Question Box •.•......•........•....•..••.•.... 35 New Periodical Articles .....•.•..•........•... 36 Dealers Catalogs 37 Duplicate Maps 39 On the Lighter Side ..............•............ 39 Volume 3, Number 2 March, 1982 base line is an official publication of the American Library Association's Hap & Geography Round Table. The purpose of base line is to provide current information on cartographic materials, other publications of interest to map and geography librarians, meetings, related governmental activities, and map librarianship. It is a medium of communication for members of the Round Table, and information and short articles of interest to Round Table members are welcomed. The opinions expressed by contributors are their cvn and do not necessarily represent those of ALA or of HAGERT, Editor: }lary Larsgaard Contributing Editors: Arthur Lakes Library James Coombs (JC), Southwest Missouri State Colorado School of Phil Hoehn (PU). University of California. Berkeley Mines Alice Hudson (AH), New York Public Library Golden CO 80401 Nancy Kandoisn (NK) , New York Public Library (303)279-0300x2697 J.B. Post (JBP), Free Library of Philadelphia Advertising Manager: INTERESTED IN BECOMING A CONTRIBUTING EDITOR? James Coombs Let the Editor know; the more, the better I Short notices and other information should be submitted to the Editor. Advertising is accepted; contact Advertising Manager (Jim Coombs, Hap Collection, 349 Library.Southwest Missouri State Univeraity, Springfield 65802; (417)836-5105).