Topographic Maps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting

Program Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting June 12–14, 2018 • Knoxville, Tennessee Institutional Support Lunar and Planetary Institute Universities Space Research Association Convener Devon Burr Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Science Organizing Committee David Williams, Chair Arizona State University Devon Burr Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Robert Jacobsen Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Bradley Thomson Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, University of Tennessee Knoxville Abstracts for this meeting are available via the meeting website at https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/pgm2018/ Abstracts can be cited as Author A. B. and Author C. D. (2018) Title of abstract. In Planetary Geologic Mappers Annual Meeting, Abstract #XXXX. LPI Contribution No. 2066, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. Guide to Sessions Tuesday, June 12, 2018 9:00 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Introduction and Mercury and Venus Maps 1:00 p.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Mars Maps 5:30 p.m. Strong Hall Poster Area Poster Session: 2018 Planetary Geologic Mappers Meeting Wednesday, June 13, 2018 8:30 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room GIS and Planetary Mapping Techniques and Lunar Maps 1:15 p.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Asteroid, Dwarf Planet, and Outer Planet Satellite Maps Thursday, June 14, 2018 8:30 a.m. Strong Hall Optional Field Trip to Appalachian Mountains Program Tuesday, June 12, 2018 INTRODUCTION AND MERCURY AND VENUS MAPS 9:00 a.m. Strong Hall Meeting Room Chairs: David Williams Devon Burr 9:00 a.m. -

Lesson 4–How to Read a Topographic Map

Lesson 4–How to Read a Topographic Map Key teaching points Suggestions for teaching Ask students to answer these ques- this lesson (3, 35-minute sessions) tions and fill in their answers on A topographic map is a representa- Activity Sheet #4: tion of a three-dimensional surface on On the poster is a topographic map a flat piece of paper. The digital eleva- of Salt Lake City. This lesson will help Which is higher, hill A or hill B? tion model on the poster is helpful in students learn how to read that map. (Answer: hill B) understanding topographic maps. Learning to use a topographic map is a difficult skill, because it requires stu- Which is steeper, hill A or hill B? Contour lines, sometimes called "level dents to visualize a three-dimensional (Answer: hill B) lines," join points of equal elevation. surface from a flat piece of paper. The closer together the contour lines Students need both practice and imag- 3. Compare a topographic map to a picture of the same place. Now have appear on a topographic map, the ination to learn to visualize hills and steeper the slope (assuming constant valleys from the contour lines on a the students look at the topographic of the same two hills. Say, "The contour intervals). topographic map. map lines you see on this map are called contour lines. Can you see why they Topographic maps have a variety of A digital terrain model of Salt Lake City uses, from planning the best route for is shown on the poster. -

Survey of India Department of Science & Technology Rashtriya Manchitran Niti NATIONAL MAP POLICY 1

Survey of India Department of Science & Technology Rashtriya Manchitran Niti NATIONAL MAP POLICY 1. PREAMBLE All socio-economic developmental activities, conservation of natural resources, planning for disaster mitigation and infrastructure development require high quality spatial data. The advancements in digital technologies have now made it possible to use diverse spatial databases in an integrated manner. The responsibility for producing, maintaining and disseminating the topographic map database of the whole country, which is the foundation of all spatial data vests with the Survey of India (SOI). Recently, SOI has been mandated to take a leadership role in liberalizing access of spatial data to user groups without jeopardizing national security. To perform this role, the policy on dissemination of maps and spatial data needs to be clearly stated. 2. OBJECTIVES • To provide, maintain and allow access and make available the National Topographic Database (NTDB) of the SOI conforming to national standards. • To promote the use of geospatial knowledge and intelligence through partnerships and other mechanisms by all sections of the society and work towards a knowledge-based society. 3. TWO SERIES OF MAPS To ensure that in the furtherance of this policy, national security objectives are fully safeguarded, it has been decided that there will be two series of maps namely (a) Defence Series Maps (DSMs)- These will be the topographical maps (on Everest/WGS-84 Datum and Polyconic/UTM Projection) on various scales (with heights, contours and full content without dilution of accuracy). These will mainly cater for defence and national security requirements. This series of maps (in analogue or digital forms) for the entire country will be classified, as appropriate, and the guidelines regarding their use will be formulated by the Ministry of Defence. -

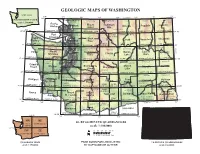

Geologic Maps of Washington

GEOLOGIC MAPS OF WASHINGTON DGER GM-53 124° 117° 123° 122° 121° 120° CANADA 119° 118° 49° 49° WASHINGTON STATE PEND DGER OFR 2000-5 WHATCOM DGER OFR 90-5 USA FERRY (scale 1:500,000) OREILLE Roche Mount Bellingham Robinson Oroville Republic Colville Harbor Baker Mtn 125° OKANOGAN DGER OFR 2003-17 48°30 USGS Map I-2660 DGER OFR 90-10 DGER OFR 90-13 48°30 CANADA DGER OFR 90-11 SAN USA Port JUAN SKAGIT DGER DGER OFR 90-12 ISLAND OFR 90-9 Cape Angeles Port Sauk Nespelem Chewelah Flattery Townsend River Twisp Omak USGS Map I-1198F DGER OFR 2003-5 DGER OFR 2003-6 DGER DGER OFR 90-14 48° USGS Map I-1198G USGS Map I -2592 OFR 95-3 DGER OFR 90-16 48° CLALLAM USGS OFR 93-233 STEVENS IDAHO SNOHOMISH DOUGLAS JEFFERSON USGS OFR 91-147 CHELAN Mount Coulee Forks Seattle Skykomish Banks Spokane Olympus River Chelan Lake Dam DGER OFR 2000-4 DGER OFR 2003-4 DGER OFR 90-17 47°30 KITSAP USGS Map I-1963 USGS Map I-1661 DGER OFR 90-6 DGER OFR 90-15 47°30 GRAYS GIS data only KING LINCOLN SPOKANE Copalis HARBOR GRANT Snoqualmie Moses Beach Shelton Tacoma Wenatchee Ritzville Rosalia MASON Pass Lake DGER OFR 2003-16 KITTITAS DGER OFR 2003-15 47° DGER OFR 87-3 USGS Map I-2538 USGS Map I-1311 DGER OFR 90-1 DGER OFR 90-2 DGER OFR 90-7 47° WHITMAN PIERCE ADAMS THURSTON Westport Chehalis Mount Priest Pullman River Centralia Yakima Connell LEWIS Rainier Rapids FRANKLIN DGER DGER OFR 87-8 DGER OFR 87-8 DGER 46°30 DGER OFR 87-11 DGER OFR 87-16 OFR 86-4 OFR 94-12 DGER OFR 94-13 DGER OFR 94-14 DGER OFR 94-6 46°30 PACIFIC GARFIELD YAKIMA DGER COLUMBIA OFR 86-3 BENTON Ilwaco WAHKIAKUM Mount Clarkston Mount Richland Walla Walla Astoria St. -

US Topo Map Users Guide

US Topo Map Users Guide April 2018. Based on Adobe Reader XI version 11.0.20 (Minor updates and corrections, November 2017.) April 2018 Updates Based on Adobe Reader DC version 2018.009.20050 In 2017, US Topo production systems were redesigned. This system change has few impacts on the design and appearance of US Topo maps, but does affect the geospatial characteristics. The previous version of this Users Guide is frozen in its current form, and applies to US Topo maps created The previous version of this Users Guide, which before approximately June 2017 and to all HTMC applies to US Topo maps created before June maps. The document you are now reading applies 2017 and to all HTMC maps, is linked from to US Topo maps created after June 2017, and https://nationalmap.gov/ustopo will be maintained into the future. US Topo maps are the current generation of USGS topographic maps. The first of these maps were published in 2009. They are modeled on the legacy 7.5-minute series of the mid-20th century, but unlike traditional topographic maps they are mass produced from GIS databases, and are published as PDF documents instead of as paper maps. US Topo maps include base data from The National Map and other sources, including roads, hydrography, contours, boundaries, woodland cover, structures, geographic names, an aerial photo image, Federal land boundaries, and shaded relief. For more information see the project web page at https://nationalmap.gov/ustopo. The Historical Topographic Map Collection (HTMC) includes all editions and all scales of USGS standard topographic quadrangle maps originally published as paper maps in the period 1884-2006. -

Chapter 13.2: Topographic Maps 1

Chapter 13.2: Topographic Maps 1 A map is a model or representation of objects and terrain in the actual environment. There are numerous types of maps. Some of the types of maps include mental, planimetric, topographic, and even treasure maps. The concept of mapping was introduced in the section using natural features. Maps are created for numerous purposes. A treasure map is used to find the buried treasure. Topographic maps were originally used for military purposes. Today, they have been used for planning and recreational purposes. Although other types of maps are mentioned, the primary focus of this section is on topographic maps. Types of Maps Mental Maps – The mind makes mental maps all the time. You drive to the grocery store. You turn right onto the boulevard. You identify a street sign, building or other landmark and know where this is where you turn. You have made a mental map. This was discussed under using natural features. Planimetric Maps – A planimetric map is a two dimensional representation of objects in the environment. Generally, planimetric maps do not include topographic representation. Road maps, Rand McNally ® and GoogleMaps ® (not GoogleEarth) are examples of planimetric maps. Topographic Maps – Topographic maps show elevation or three-dimensional topography two dimensionally. Topographic maps use contour lines to show elevation. A chart refers to a nautical chart. Nautical charts are topographic maps in reverse. Rather than giving elevation, they provide equal levels of water depth. Topographic Maps Topographic maps show elevation or three-dimensional topography two dimensionally. Topographic maps use contour lines to show elevation. -

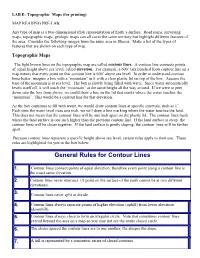

General Rules for Contour Lines

6/30/2015 EASC111LabEFor Printing LAB E: Topographic Maps (for printing) MAP READING PRELAB: Any type of map is a twodimensional (flat) representation of Earth’s surface. Road maps, surveying maps, topographic maps, geologic maps can all cover the same territory but highlight different features of the area. Consider the following images from the same area in Illinois. Make a list of the types of features that are shown on each type of map. Topographic Maps The light brown lines on the topographic map are called contour lines. A contour line connects points of equal height above sea level, called elevation. For example, a 600’ (six hundred foot) contour line on a map means that every point on that contour line is 600’ above sea level. In order to understand contour lines better, imagine a box with a “mountain” in it with a clear plastic lid on top of the box. Assume the base of the mountain is at sea level. The box is slowly being filled with water. Since water automatically levels itself off, it will touch the “mountain” at the same height all the way around. If we were to peer down into the box from above, we could draw a line on the lid that marks where the water touches the “mountain”. This would be a contour line for that elevation. As the box continues to fill with water, we would draw contour lines at specific intervals, such as 1”. Each time the water level rises one inch, we will draw a line marking where the water touches the land. -

Maps and Charts

Name:______________________________________ Maps and Charts Lab He had bought a large map representing the sea, without the least vestige of land And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be, a map they could all understand - Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark Map Projections: All maps and charts produce some degree of distortion when transferring the Earth's spherical surface to a flat piece of paper or computer screen. The ways that we deal with this distortion give us various types of map projections. Depending on the type of projection used, there may be distortion of distance, direction, shape and/or area. One type of projection may distort distances but correctly maintain directions, whereas another type may distort shape but maintain correct area. The type of information we need from a map determines which type of projection we might use. Below are two common projections among the many that exist. Can you tell what sort of distortion occurs with each projection? 1 Map Locations The latitude-longitude system is the standard system that we use to locate places on the Earth’s surface. The system uses a grid of intersecting east-west (latitude) and north-south (longitude) lines. Any point on Earth can be identified by the intersection of a line of latitude and a line of longitude. Lines of latitude: • also called “parallels” • equator = 0° latitude • increase N and S of the equator • range 0° to 90°N or 90°S Lines of longitude: • also called “meridians” • Prime Meridian = 0° longitude • increase E and W of the P.M. -

(GIS)-Based Approach to Derivative Map Production and Visualizing Bedrock Topography Within the Town of Rutland, Vermont, USA

ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2014, 3, 130-142; doi:10.3390/ijgi3010130 OPEN ACCESS ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information ISSN 2220-9964 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijgi/ Article A Geographic Information Systems (GIS)-Based Approach to Derivative Map Production and Visualizing Bedrock Topography within the Town of Rutland, Vermont, USA John G. Van Hoesen Department of Environmental Studies, Green Mountain College, One Brennan Circle, Poultney, VT 05764, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-802-287-8387; Fax: +1-802-287-8080 Received: 17 December 2013; in revised form: 21 January 2014 / Accepted: 22 January 2014 / Published: 29 January 2014 Abstract: Many state and national geological surveys produce map products from surficial and bedrock geologic maps as a value-added deliverable for a variety of stakeholders. Improvements in powerful geostatistical exploratory tools and robust three-dimensional capabilities within geographic information systems (GIS) can facilitate the production of derivative products. In addition to providing access to geostatistical functions, many software packages are also capable of rendering three-dimensional visualizations using spatially distributed point data. A GIS-based approach using ESRI’s® Geostatistical Analyst® was used to create derivative maps depicting surficial overburden, bedrock topography, and potentiometric surface using well data and bedrock exposures. This methodology describes the importance and relevance of creating three-dimensional visualizations in tandem with traditional two-dimensional map products. These 3D products are especially useful for town managers and planners—often unfamiliar with interpreting two-dimensional geologic map products—so they can better visualize and understand the relationships between surficial overburden and potential groundwater resources. -

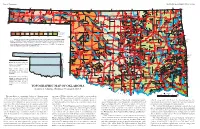

TOPOGRAPHIC MAP of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 2, Topographic EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 Contour lines (in feet) are generalized from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps (scale, 1:250,000). Principal meridians and base lines (dotted black lines) are references for subdividing land into sections, townships, and ranges. Spot elevations ( feet) are given for select geographic features from detailed topographic maps (scale, 1:24,000). The geographic center of Oklahoma is just north of Oklahoma City. Dimensions of Oklahoma Distances: shown in miles (and kilometers), calculated by Myers and Vosburg (1964). Area: 69,919 square miles (181,090 square kilometers), or 44,748,000 acres (18,109,000 hectares). Geographic Center of Okla- homa: the point, just north of Oklahoma City, where you could “balance” the State, if it were completely flat (see topographic map). TOPOGRAPHIC MAP OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. Johnson, Oklahoma Geological Survey This map shows the topographic features of Oklahoma using tain ranges (Wichita, Arbuckle, and Ouachita) occur in southern contour lines, or lines of equal elevation above sea level. The high- Oklahoma, although mountainous and hilly areas exist in other parts est elevation (4,973 ft) in Oklahoma is on Black Mesa, in the north- of the State. The map on page 8 shows the geomorphic provinces The Ouachita (pronounced “Wa-she-tah”) Mountains in south- 2,568 ft, rising about 2,000 ft above the surrounding plains. The west corner of the Panhandle; the lowest elevation (287 ft) is where of Oklahoma and describes many of the geographic features men- eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas is a curved belt of forested largest mountainous area in the region is the Sans Bois Mountains, Little River flows into Arkansas, near the southeast corner of the tioned below. -

Application of Geologic Mapping and Geographic Information Systems To

APPLICATION OF GEOLOGIC MAPPING AND GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS TO DELINEATE SENSITIVE KARST AREAS FOR LAND-USE DECISIONS Jim Cichon, Alex Wood, Alan Baker and Jon Arthur Florida Geological Survey, Hydrogeology Program The Problem: The Floridan aquifer system (FAS), a thick sequence of Tertiary carbonates, is the major fresh water resource in the Florida panhandle. The expanding population of the State places an ever-growing demand on the fresh-water resources through increased land and water use. Overburden comprised of surficial aquifer sediments or intermediate confining unit (ICU) sediments may act to protect the FAS from potential contamination sources where it is present. This overburden can be several hundred feet thick where it provides variable confinement for the FAS, or it can be thin to absent in areas where carbonate units comprising the FAS are exposed at or near land surface. In areas where the overburden is thin to absent, the potential for karst terrain development is increased. Sinkholes and collapse features are more common and occur at a much Figure 1: Generalized geologic map of northwestern Florida (modified from Scott, et al. 2001). greater rate than in well-confined areas. The nature of karst terrain provides preferential flow paths for surface water to enter the underlying aquifer system, and therefore aquifer systems underlying karst terrain are at a greater risk to surface contamination potential. The Geologic Map: In Florida, areas of karst topography are associated with, but not limited to shallow and exposed carbonate rocks. The state geologic map of Florida and associated cross-sections provide this detailed lithologic information (Scott, et al, 2001). -

Observations on USGS-State Cooperative Mapping

DR.WALLACE W. HACAN Director Kentucky Geological Survey (Ret.) Observations on USGS-State Cooperative Mapping HE DICTIONARY defines the word cooper- selective based on immediate needs of our T ate to mean: to work together willingly country. A state may attract the uscs to map for a common purpose. Thus, when The in it, or accelerate mapping in progress, by United States Geological Survey and a state entrance into a cooperative program. This agency enter into a cooperative agreement, also reduces the cost to the federal govern- they have definite objectives which involve ment, and produces a base map sooner, and both state and federal agencies. The signed consequently enhances economic develop- agreements are quite simple and indicate ment in the State. the nature of the funding, who performs the Fourteen states now have complete 7.5 operations, who owns the original materials, minute topographic map coverage on a the mutual considerations, and the publica- 1:24,000 scale, most of which was done in tion of the results. cooperative programs. Last year in FY 1978, There are several types of cooperative 38 states and Puerto Rico contributed $3.5 programs: million toward the National Mapping Pro- The uses furnishes the personnel, super- -gram, .- primarily for new 7.5 minute topo- vises personnel and operations, in field graphic mapping. Some states' cooperative and ofice, reviews, approves, does cartog- mapping agreements included: raphy, and publishes. Plans and priorities are formulated mutually, and funds are High-altitude aerial photography, photo- matched. inspection, and photorevision of published 7.5 minute maps in the states of Indiana, This is the same, except by agreement the state furnishes some of the personnel and Kansas, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Virginia.