Chapter 13.2: Topographic Maps 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 4–How to Read a Topographic Map

Lesson 4–How to Read a Topographic Map Key teaching points Suggestions for teaching Ask students to answer these ques- this lesson (3, 35-minute sessions) tions and fill in their answers on A topographic map is a representa- Activity Sheet #4: tion of a three-dimensional surface on On the poster is a topographic map a flat piece of paper. The digital eleva- of Salt Lake City. This lesson will help Which is higher, hill A or hill B? tion model on the poster is helpful in students learn how to read that map. (Answer: hill B) understanding topographic maps. Learning to use a topographic map is a difficult skill, because it requires stu- Which is steeper, hill A or hill B? Contour lines, sometimes called "level dents to visualize a three-dimensional (Answer: hill B) lines," join points of equal elevation. surface from a flat piece of paper. The closer together the contour lines Students need both practice and imag- 3. Compare a topographic map to a picture of the same place. Now have appear on a topographic map, the ination to learn to visualize hills and steeper the slope (assuming constant valleys from the contour lines on a the students look at the topographic of the same two hills. Say, "The contour intervals). topographic map. map lines you see on this map are called contour lines. Can you see why they Topographic maps have a variety of A digital terrain model of Salt Lake City uses, from planning the best route for is shown on the poster. -

Survey of India Department of Science & Technology Rashtriya Manchitran Niti NATIONAL MAP POLICY 1

Survey of India Department of Science & Technology Rashtriya Manchitran Niti NATIONAL MAP POLICY 1. PREAMBLE All socio-economic developmental activities, conservation of natural resources, planning for disaster mitigation and infrastructure development require high quality spatial data. The advancements in digital technologies have now made it possible to use diverse spatial databases in an integrated manner. The responsibility for producing, maintaining and disseminating the topographic map database of the whole country, which is the foundation of all spatial data vests with the Survey of India (SOI). Recently, SOI has been mandated to take a leadership role in liberalizing access of spatial data to user groups without jeopardizing national security. To perform this role, the policy on dissemination of maps and spatial data needs to be clearly stated. 2. OBJECTIVES • To provide, maintain and allow access and make available the National Topographic Database (NTDB) of the SOI conforming to national standards. • To promote the use of geospatial knowledge and intelligence through partnerships and other mechanisms by all sections of the society and work towards a knowledge-based society. 3. TWO SERIES OF MAPS To ensure that in the furtherance of this policy, national security objectives are fully safeguarded, it has been decided that there will be two series of maps namely (a) Defence Series Maps (DSMs)- These will be the topographical maps (on Everest/WGS-84 Datum and Polyconic/UTM Projection) on various scales (with heights, contours and full content without dilution of accuracy). These will mainly cater for defence and national security requirements. This series of maps (in analogue or digital forms) for the entire country will be classified, as appropriate, and the guidelines regarding their use will be formulated by the Ministry of Defence. -

Digital Mapping & Spatial Analysis

Digital Mapping & Spatial Analysis Zach Silvia Graduate Community of Learning Rachel Starry April 17, 2018 Andrew Tharler Workshop Agenda 1. Visualizing Spatial Data (Andrew) 2. Storytelling with Maps (Rachel) 3. Archaeological Application of GIS (Zach) CARTO ● Map, Interact, Analyze ● Example 1: Bryn Mawr dining options ● Example 2: Carpenter Carrel Project ● Example 3: Terracotta Altars from Morgantina Leaflet: A JavaScript Library http://leafletjs.com Storytelling with maps #1: OdysseyJS (CartoDB) Platform Germany’s way through the World Cup 2014 Tutorial Storytelling with maps #2: Story Maps (ArcGIS) Platform Indiana Limestone (example 1) Ancient Wonders (example 2) Mapping Spatial Data with ArcGIS - Mapping in GIS Basics - Archaeological Applications - Topographic Applications Mapping Spatial Data with ArcGIS What is GIS - Geographic Information System? A geographic information system (GIS) is a framework for gathering, managing, and analyzing data. Rooted in the science of geography, GIS integrates many types of data. It analyzes spatial location and organizes layers of information into visualizations using maps and 3D scenes. With this unique capability, GIS reveals deeper insights into spatial data, such as patterns, relationships, and situations - helping users make smarter decisions. - ESRI GIS dictionary. - ArcGIS by ESRI - industry standard, expensive, intuitive functionality, PC - Q-GIS - open source, industry standard, less than intuitive, Mac and PC - GRASS - developed by the US military, open source - AutoDESK - counterpart to AutoCAD for topography Types of Spatial Data in ArcGIS: Basics Every feature on the planet has its own unique latitude and longitude coordinates: Houses, trees, streets, archaeological finds, you! How do we collect this information? - Remote Sensing: Aerial photography, satellite imaging, LIDAR - On-site Observation: total station data, ground penetrating radar, GPS Types of Spatial Data in ArcGIS: Basics Raster vs. -

US Topo Map Users Guide

US Topo Map Users Guide April 2018. Based on Adobe Reader XI version 11.0.20 (Minor updates and corrections, November 2017.) April 2018 Updates Based on Adobe Reader DC version 2018.009.20050 In 2017, US Topo production systems were redesigned. This system change has few impacts on the design and appearance of US Topo maps, but does affect the geospatial characteristics. The previous version of this Users Guide is frozen in its current form, and applies to US Topo maps created The previous version of this Users Guide, which before approximately June 2017 and to all HTMC applies to US Topo maps created before June maps. The document you are now reading applies 2017 and to all HTMC maps, is linked from to US Topo maps created after June 2017, and https://nationalmap.gov/ustopo will be maintained into the future. US Topo maps are the current generation of USGS topographic maps. The first of these maps were published in 2009. They are modeled on the legacy 7.5-minute series of the mid-20th century, but unlike traditional topographic maps they are mass produced from GIS databases, and are published as PDF documents instead of as paper maps. US Topo maps include base data from The National Map and other sources, including roads, hydrography, contours, boundaries, woodland cover, structures, geographic names, an aerial photo image, Federal land boundaries, and shaded relief. For more information see the project web page at https://nationalmap.gov/ustopo. The Historical Topographic Map Collection (HTMC) includes all editions and all scales of USGS standard topographic quadrangle maps originally published as paper maps in the period 1884-2006. -

Maps and Charts

Name:______________________________________ Maps and Charts Lab He had bought a large map representing the sea, without the least vestige of land And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be, a map they could all understand - Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark Map Projections: All maps and charts produce some degree of distortion when transferring the Earth's spherical surface to a flat piece of paper or computer screen. The ways that we deal with this distortion give us various types of map projections. Depending on the type of projection used, there may be distortion of distance, direction, shape and/or area. One type of projection may distort distances but correctly maintain directions, whereas another type may distort shape but maintain correct area. The type of information we need from a map determines which type of projection we might use. Below are two common projections among the many that exist. Can you tell what sort of distortion occurs with each projection? 1 Map Locations The latitude-longitude system is the standard system that we use to locate places on the Earth’s surface. The system uses a grid of intersecting east-west (latitude) and north-south (longitude) lines. Any point on Earth can be identified by the intersection of a line of latitude and a line of longitude. Lines of latitude: • also called “parallels” • equator = 0° latitude • increase N and S of the equator • range 0° to 90°N or 90°S Lines of longitude: • also called “meridians” • Prime Meridian = 0° longitude • increase E and W of the P.M. -

(GIS)-Based Approach to Derivative Map Production and Visualizing Bedrock Topography Within the Town of Rutland, Vermont, USA

ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2014, 3, 130-142; doi:10.3390/ijgi3010130 OPEN ACCESS ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information ISSN 2220-9964 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijgi/ Article A Geographic Information Systems (GIS)-Based Approach to Derivative Map Production and Visualizing Bedrock Topography within the Town of Rutland, Vermont, USA John G. Van Hoesen Department of Environmental Studies, Green Mountain College, One Brennan Circle, Poultney, VT 05764, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-802-287-8387; Fax: +1-802-287-8080 Received: 17 December 2013; in revised form: 21 January 2014 / Accepted: 22 January 2014 / Published: 29 January 2014 Abstract: Many state and national geological surveys produce map products from surficial and bedrock geologic maps as a value-added deliverable for a variety of stakeholders. Improvements in powerful geostatistical exploratory tools and robust three-dimensional capabilities within geographic information systems (GIS) can facilitate the production of derivative products. In addition to providing access to geostatistical functions, many software packages are also capable of rendering three-dimensional visualizations using spatially distributed point data. A GIS-based approach using ESRI’s® Geostatistical Analyst® was used to create derivative maps depicting surficial overburden, bedrock topography, and potentiometric surface using well data and bedrock exposures. This methodology describes the importance and relevance of creating three-dimensional visualizations in tandem with traditional two-dimensional map products. These 3D products are especially useful for town managers and planners—often unfamiliar with interpreting two-dimensional geologic map products—so they can better visualize and understand the relationships between surficial overburden and potential groundwater resources. -

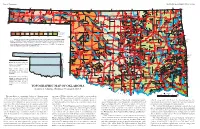

TOPOGRAPHIC MAP of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 2, Topographic EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 Contour lines (in feet) are generalized from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps (scale, 1:250,000). Principal meridians and base lines (dotted black lines) are references for subdividing land into sections, townships, and ranges. Spot elevations ( feet) are given for select geographic features from detailed topographic maps (scale, 1:24,000). The geographic center of Oklahoma is just north of Oklahoma City. Dimensions of Oklahoma Distances: shown in miles (and kilometers), calculated by Myers and Vosburg (1964). Area: 69,919 square miles (181,090 square kilometers), or 44,748,000 acres (18,109,000 hectares). Geographic Center of Okla- homa: the point, just north of Oklahoma City, where you could “balance” the State, if it were completely flat (see topographic map). TOPOGRAPHIC MAP OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. Johnson, Oklahoma Geological Survey This map shows the topographic features of Oklahoma using tain ranges (Wichita, Arbuckle, and Ouachita) occur in southern contour lines, or lines of equal elevation above sea level. The high- Oklahoma, although mountainous and hilly areas exist in other parts est elevation (4,973 ft) in Oklahoma is on Black Mesa, in the north- of the State. The map on page 8 shows the geomorphic provinces The Ouachita (pronounced “Wa-she-tah”) Mountains in south- 2,568 ft, rising about 2,000 ft above the surrounding plains. The west corner of the Panhandle; the lowest elevation (287 ft) is where of Oklahoma and describes many of the geographic features men- eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas is a curved belt of forested largest mountainous area in the region is the Sans Bois Mountains, Little River flows into Arkansas, near the southeast corner of the tioned below. -

What Is Geovisualization? to the Growing Field of Geovisualization

This issue of GeoMatters is devoted What is Geovisualization? to the growing field of geovisualization. Brian McGregor uses geovisualiztion to by Joni Storie produce animated maps showing settle- ment patterns of Hutterite colonies. Dr. Marc Vachon’s students use it to produce From a cartography perspective, dynamic presentation options to com- videos about urban visualization (City geovisualization represents a change in municate knowledge. For example, at- Hall and Assiniboine Park), while Dr. how knowledge is formed and repre- lases require extra planning compared Chris Storie shows geovisualiztion for sented. Traditional cartography is usu- to individual maps, structurally they retail mapping in Winnipeg. Also in this issue Honours students describe their ally seen a visualization (a.k.a. map) could include hundreds of maps, and thesis projects for the upcoming collo- that is presented after the conclusion all the maps relate to each other. Dr. quium next March, Adrienne Ducharme is reached to emphasize or compliment Danny Blair and Dr. Ian Mauro, in the tells us about her graduate research at the research conclusions. Geovisual- Department of Geography, provide an ELA, we have a report about Cultivate ization changes this format by incor- excellent example of this integration UWinnipeg and our alumni profile fea- porating spatial data into the analysis with the Prairie Climate Atlas (http:// tures Michelle Méthot (Smith). (O’Sullivan and Unwin, 2010). Spatial www.climateatlas.ca/). The combina- Please feel free to pass this newsletter data, statistics and analysis are used to tion of maps with multimedia provides to anyone with an interest in geography. answer questions which contribute to for better understanding as well as en- Individuals can also see GeoMatters at the Geography website, or keep up with the conclusion that is reached within riched and informative experiences of us on Facebook (Department of Geog- the research. -

Loading and Managing OS Mastermap Topography Layer

Loading and Managing OS MasterMap® Topography Layer An ESRI (UK) White Paper Confidentiality Statement This document contains information which is confidential to ESRI (UK) Limited. No part of this document should be reproduced or revealed to third parties without the express permission of ESRI (UK) Limited. © 2008 ESRI (UK) Ltd and its third party licensors. All rights reserved. ESRI (UK) Ltd Millennium House 65 Walton Street Aylesbury Buckinghamshire HP21 7QG Tel: +44 (0) 1296 745500 Fax: +44 (0) 1296 745544 Website: www.esriuk.com Released: 10/11/2008 Version: 5.3 Document History: Version Date Changes 1.0 31/08/2003 Document initial release. 2.0 16/12/2003 Document Updated/ Name Change. 3.0 23/11/2004 Document Reviewed/ Name Change. 4.0 05/06/05 OS MasterMap v6 4.1 11/08/05 Edits after Ordnance Survey review 5.0 19/05/2006 Technology updates 5.1 19/05/2006 Len Laver and Wai-Ming Lee review and edit of sections relevant to OS MasterMap-to-Go service 5.2 01/04/2008 Updated to new ESRI (UK) branding and style. 5.3 10/11/2008 Updates for new ‘minimise load on database’ option. © ESRI (UK) 2008 2 Contents Page 1. Introduction ........................................................................... 5 2. OS MasterMap® ...................................................................... 6 2.1. What is OS MasterMap? ............................................................... 6 2.2. Benefits of OS MasterMap ............................................................ 7 2.3. TOIDs and TOID-Associations ....................................................... 8 2.4. How OS MasterMap Topography Layer is Structured ........................ 9 2.5. OS MasterMap Topography Layer Data Schema ............................. 10 3. OS MasterMap Topography Layer Data Supply ................... 16 3.1. Initial OS MasterMap Topography Layer Data Supply ..................... -

The Topography of the Earth's Surface

CHAPTER 3 THE LAY OF THE LAND: THE TOPOGRAPHY OF THE EARTH’S SURFACE 1. LATITUDE AND LONGITUDE 1.1 You probably know already that the basic coordinate system that’s used to describe the position of a point on the Earth's surface is latitude and longitude. In this system (Figure 3-1), the Earth is imagined to be cut by a series of planes that pass through the north–south axis of rotation. The intersection of such a plane with the Earth’s surface is called a line (really a curve) of longitude, or a meridian. Longitude is measured in degrees, from zero to 360. One meridian (the one that passes through Greenwich, England) is called the prime meridian, and longitude is measured 180 degrees to the west of that and 180 degrees to the east of that. The opposite meridian, 180 degrees around the world from the prime meridian (and the intersection of the longitude plane with the other side of the world) lies about in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. 1.2 One consequence of this definition of longitude is that the spacing between two meridians gets smaller as you go north or south from the equator. Think about this the next time you fly west in a jetliner: You would have to move awfully fast to keep up with the sun, and land at the same time of day you took off, if you're flying along the equator, but if you're flying east to west in the far north or far south on the earth, you could easily arrive at your destination a lot earlier in the day than you took off! 1.3 The other element of the coordinate system is a series of latitude circles (Figure 3-1). -

Bibliographical Index

Bibliographical Index BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ACCESS TO THIS VOLUME Bacon, Roger. Opus Majus. 305, 322, 345 Basil, Saint. Homilies. 328 Three modes of access to bibliographical information are used Bede, the Venerable. De natura rerum. 137 in this volume: the footnotes; the bibliographies; and the Bib ---. De temporum ratione. 321 liographical Index. The footnotes provide the full form of a reference the first Cassiodorus. Institutiones divinarum et saecularium time it is cited in each chapter with short-title versions in litterarum. 172, 255, 259, 261 subsequent citations. In each of the short-title references, the Cato the Elder. Origines. 205 note number of the fully cited work is given in parentheses. Censorinus. De die natalie 255 The bibliographies following each chapter provide a selec Chaucer, Geoffrey. Prologue to the Canterbury Tales. 387 tive list of major books and articles relevant to its subject Cicero. Arataea (translation of Aratus's versification of matter. Eudoxus's Phaenomena). 143 The Bibliographical Index comprises a complete list, ar ---. Letters to Atticus. 255 ranged alphabetically by author's name, of all works cited in ---. De natura deorum. 160,168 the footnotes. Numbers in bold type indicate the pages on --. The Republic. 159, 160, 255 which references to these works can be found. This index is ---. Tusculan Disputations. 160 divided into two parts. The first part identifies the texts of Cleomedes. De motu circulari. 152, 154, 169 classical and medieval authors. The second part lists the mod Cosmas Indicopleustes. Christian Topography. 143, 144, ern literature. 261 Ctesias of Cnidus. Indica. 149 TEXTS OF CLASSICAL AND MEDIEVAL ---. Persica. 149 AUTHORS Dicuil. -

49 Chapter 5 Topographical Maps

Topographical Maps Chapter 5 Topographical Maps You know that the map is an important geographic tool. You also know that maps are classified on the basis of scale and functions. The topographical maps, which have been referred to in Chapter 1 are of utmost importance to geographers. They serve the purpose of base maps and are used to draw all the other maps. Topographical maps, also known as general purpose maps, are drawn at relatively large scales. These maps show important natural and cultural features such as relief, vegetation, water bodies, cultivated land, settlements, and transportation networks, etc. These maps are prepared and published by the National Mapping Organisation of each country. For example, the Survey of India prepares the topographical maps in India for the entire country. The topographical maps are drawn in the form of series of maps at different scales. Hence, in the given series, all maps employ the same reference point, scale, projection, conventional signs, symbols and colours. The topographical maps in India are prepared in two series, i.e. India and Adjacent Countries Series and The International Map Series of the World. India and Adjacent Countries Series: Topographical maps under India and Adjacent Countries Series were prepared by the Survey of India till the coming into existence of Delhi Survey Conference in 1937. Henceforth, the preparation of maps for the adjoining 49 countries was abandoned and the Survey of India confined itself to prepare and publish the topographical maps for India as per the specifications laid down for the International Map Series of the World.