Cover Rebuilding West Africas Food Potential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minmap Region Du Littoral Synthese Des Donnees Sur La Base Des Informations Recueillies

MINMAP REGION DU LITTORAL SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° page Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine de de Douala 94 89 179 421 671 3 2 Communité Urbaine d'édéa 5 89 000 000 14 3 Communité Urbaine de Nkongsamba 6 198 774 344 15 4 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 17 718 555 000 16 Département du Moungo 5 Services déconcentrés départementaux 5 145 000 000 18 6 Commune de BARE BAKEM 2 57 000 000 18 7 Commune de BONALEA 3 85 500 000 19 8 Commune de DIBOMBARI 3 105 500 000 19 9 Commune de LOUM 16 445 395 149 19 10 Commune de MANJO 8 132 000 000 21 11 Commune de MBANGA 3 108 000 000 22 12 Commune de MELONG 12 173 500 000 22 13 Commune de NJOMBE PENJA 5 132 000 000 24 14 Commune d'EBONE 12 299 500 000 25 15 Commune de MOMBO 3 77 000 000 26 16 Commune de NKONGSAMBA I 1 27 000 000 26 17 Commune de NKONGSAMBA II 3 59 250 000 27 18 Commune de NKONGSAMBA III 2 87 000 000 27 TOTAL Département 78 1 933 645 149 Département du Nkam 19 Services déconcentrés départementaux 12 232 596 000 28 20 Commune de NKONDJOCK 16 258 623 000 29 21 Commune de YABASSI 14 221 000 000 31 22 Commune de YINGUI 4 53 500 000 33 23 Commune de NDOBIAN 17 345 418 000 33 TOTAL Département 63 1 111 137 000 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 24 Services déconcentrés départementaux 8 90 960 000 36 25 Commune de Dibamba 3 72 000 000 37 26 Commune de Dizangue 5 88 500 000 37 27 Commune de MASSOCK 4 233 230 000 38 28 Commune de MOUANKO 15 582 770 000 38 29 Commune de NDOM 12 339 237 000 40 Nbre de N° Désignation -

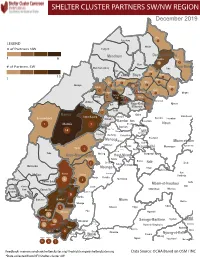

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Programmation De La Passation Et De L'exécution Des Marchés Publics

PROGRAMMATION DE LA PASSATION ET DE L’EXÉCUTION DES MARCHÉS PUBLICS EXERCICE 2021 JOURNAUX DE PROGRAMMATION DES MARCHÉS DES SERVICES DÉCONCENTRÉS ET DES COLLECTIVITÉS TERRITORIALES DÉCENTRALISÉES RÉGION DU LITTORAL EXERCICE 2021 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° page Marchés 1 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 11 476 050 000 3 2 Communauté Urbaine de Nkongsamba 143 49 894 418 496 4 3 Communauté Urbaine de Nkongsamba 1 125 000 000 16 Département du Moungo 4 Services déconcentrés départementaux 2 38 000 000 17 5 Commune de BARE BAKEM 9 312 790 000 17 6 Commune de BONALEA 24 412 000 000 17 7 Commune de DIBOMBARI 11 273 300 000 19 8 Commune de LOUM 8 186 600 000 20 9 Commune de MANJO 8 374 700 000 21 10 Commune de MBANGA 9 222 600 000 21 11 Commune de MELONG 13 293 140 184 22 12 Commune de NJOMBE PENJA 5 221 710 000 23 13 Commune d'EBONE 10 294 400 000 24 14 Commune de MOMBO 6 142 500 000 24 15 Commune de NKONGSAMBA I 11 245 833 000 25 16 Commune de NKONGSAMBA II 11 316 000 000 26 17 Commune de NKONGSAMBA III 6 278 550 000 27 TOTAL Département 133 3 612 123 184 Département du Nkam 18 Services déconcentrés départementaux 2 16 000 000 28 19 Commune de NDOBIAN 12 309 710 000 28 20 Commune de NKONDJOCK 8 377 000 000 29 21 Commune de YABASSI 21 510 500 000 29 22 Commune de YINGUI 11 241 000 000 31 TOTAL Département 54 1 454 210 000 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 23 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 371 600 000 32 24 Commune de Dibamba 13 328 650 000 32 -

Cameroon, Cocoa's Other Nation

MAJOR PROJECTS AGRICULTURE ENERGY BUSINESS IN MINING INDUSTRY SERVICES FINANCE December 2017/January 2018 - N° 58/59 2018 December 2017/January CAMEROON Cameroon, cocoa’s other nation Pierre Zumbach: “An 398,000 jobs created in international promotion 2017, what’s more? tool each year” FREE - CANNOT BE SOLD BUSINESSIN CAMEROON .COM Daily business news from Cameroon Compatible with iPads, smartphones or tablets APP AVAILABLE ON IOS AND ANDROID 3 Yasmine Bahri-Domon “Well done” ameroon was in 2017 the completion, and Wouri’s second bridge member-State of the econom- has come online. Infrastructures are ic and monetary community being developed at a good pace. It is of Central Africa (CEMAC) obvious that Cameroon would have Cthat resisted the most to the shocks of fared better if not for the severe drop in the global economic crisis. Leveraging prices of commodities (coffee, cocoa, on its diversified agricultural produc- rubber…) However, you will discover tion, and the efficient multiplication of in this edition of our magazine that tax and custom revenue sources, the the government gradually creates country was able to keep its economic better perspectives for the country’s growth rate above 4.5% against 2.5% for cocoa, which is one of the pillars of its its neighbors. In the Doing Business, its agriculture. ranking has significantly increased. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Overall, 2017 was a year where many fact lauded the various measures taken palpable and multifaceted realizations by the government in face of economic have been achieved, to the general sat- challenges. Cameroon actually did not isfaction of Cameroon’s international exclusively focus on its oil revenues. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Kribi Power Project

AES SONEL Kribi Power Project Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Report January 2010 AES Sonel Kribi Power Project, Cameroon Revision Schedule Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Report January 2010 Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 January 2010 Combined ESIA Becky Humphrey Julie Raynor Andrew McNab & Addendum Environmental Consultant Principal Environmental Director Reports Consultant Danny Duce Air Quality Specialist Scott Wilson 6-8 Greencoat Place London This document has been prepared in accordance with the scope of Scott Wilson's appointment with its client and is subject to the terms of that appointment. It is addressed SW1P 1PL to and for the sole and confidential use and reliance of Scott Wilson's client. Scott Wilson UK accepts no liability for any use of this document other than by its client and only for the purposes for which it was prepared and provided. No person other than the client may copy (in whole or in part) use or rely on the contents of this document, without the prior written permission of the Company Secretary of Scott Wilson Ltd. Any advice, opinions, Tel 0044 (0) 20 7798 5000 or recommendations within this document should be read and relied upon only in the Fax 0044 (0) 20 7798 5001 context of the document as a whole. The contents of this document do not provide legal or tax advice or opinion. © Scott Wilson Ltd 2010 www.scottwilson.com AES Sonel Kribi Power Project, Cameroon Table of Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................1-1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Terms of Reference...................................................................................................... -

Chapter 16. Enhancing Cassava Marketing and Processing in Cameroon 505

Chapter 16 Enhancing cassava marketing and processing in Cameroon: Drivers, constraints, and prospects of the value chain* Tolly Lolo EMMANUEL1 * Correct citation: Emmanuel, T. (2013), Enhancing Cassava Marketing and Processing in Cameroon: Drivers, Constraints, and Prospects of the Value Chain, In: Rebuilding West Africa’s Food Potential, A. Elbehri (ed.), FAO/IFAD. 1 The author is consultant with PNDRT (Programme National des Racines et Tubercules). The article is based on various documents, studies and reports on cassava value chain in Cameroon and on the author experience with the IFAD- funded PNDRT program on cassava in Cameroon. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 505 2. A General overview of the cassava value chain in Cameroon 506 2.1 Contribution of the cassava value chain to the agricultural sector 506 2.2 Stylized facts on consumption 507 2.3 Cassava production in Cameroon 509 2.4 Market analysis of cassava supply and demand 510 3. The downstream nodes of the cassava value chain 513 3.1 Large wholesalers 514 3.2 Retailers 516 3.3 Exporters 517 3.4 Modern retailing channels 519 4. Constraints and opportunities for the cassava value chain in Cameroon 520 4.1 The main constraints and bottlenecks in the cassava value chain 521 4.2 Cassava producers and processors’ organizations 522 4.3 Processing and marketing capacities of cassava producers 524 5. Policies and initiatives to revamp Cameroon’s cassava value chain 527 5.1 Current policies for Cassava in Cameroon 527 5.2 Initiatives required to revamp the Cameroon’s cassava value chain 528 6. Conclusion and general recommendations 533 7. -

Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralization

MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION AND DECENTRALIZATION DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL PROTECTION Cameroon Civil Protection Report, 2008/2009 Civil defence through life-saving actions With assistance from: • United Nations Development Programme, UNDP • United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF • Cooperation and Cultural Action Service, French Embassy SCAC • National Hydrocarbons Company, SNH • Local Council Support Fund for Mutual Assistance, FEICOM • National Civil Engineering Laboratory, LABOGENIE Copyright © 2009 by DPC/MINATD Cameroon Civil Protection Report, 2008/2009 Theme: Civil defence through life - saving actions Initiative and coordination: Department of Civil Protection Published by: The Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralisation, MINATD Supported by: - United Nations Development Programme, UNDP - United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF - Cooperation and Cultural Action Service, French Embassy, SCAC - National Hydrocarbons Corporation, SNH - Local Council Support Fund for Mutual Assistance, FEICOM - National Civil Engineering Laboratory, LABOGENIE Consultant: Cabinet White Dove Company, BP 3774 Yaounde Editors: Guy KETCHATCHAM NGAMY ([email protected]) and Franklin Ludovic KAMTCHE Translation team leader: UBANAKO Valentine NJENDE Supervision: Minister of State, Minister of Territorial Administration and Decentralisation, MINATD This book is the sixth edition of a yearly publication on civil protection in Cameroon. All events reported cover the period between 1 December 2007 and 30 November 2008. Some of the views herein -

Republique Du Cameroun Republic of Cameroon

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX - TRAVAIL - PATRIE PEACE - WORK - FATHERLAND JOURNAL DES PROJETS PAR CHAPITRE, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJET (DETAILS DES PROJETS D'INVESTISSEMENT) PROJECT LOG-BOOK PER HEAD, PROGRAMME, ACTION ET PROJECT(DETAILS OF INVESTMENT PROJECT) Exercice/ Financial year : 2016 Chapitre 07 MINISTERE DE L'ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION Head MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION AND DECENTRALIZATION Programme 092 MODERNISATION DE L'ADMINISTRATION DU TERRITOIRE Code service: 2004 MODERNISATION OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION Action 04 OPTIMISATION DES CAPACITES OPERATIONNELLES DES AUTORITES ADMINISTRATIVES OPTIMIZING THE OPERATIONAL CAPACITIES ADMINISTRATIVE AUTHORITIES En Milliers de FCFA In Thousand CFAF Région/ Region Tache Num Montant AE Montant CP Année Structure Poste Comptable Localité Unité physique Mode gestion Gestionnaire Département/ Division Task Num AE Amount CP Amount Start Structure Accounting sta. Locality Unité physique Management Gestionnaire Year Arrondiss./ Sub-division Paragraphe Réhabilitation des Sous-Préfectures Projet/Project Rehabilitation of Sub-Divisional Offices Pouma: Réhabilitation Sous-Préfecture 6 100 6 100 2016 47 14 44 LITTORAL PERCEPTION POUMA 2220 222032 - Un Service Délégation SOUS-PREFET POUMA d’une autorité Automatique POUMA Pouma: Rehabilitation of the Sub-Divisional Office SOUS- SANAGA MARITIME administrative réhabilité PRÉFECTURE DE POUMA [Qté:1] POUMA Total Projet/Project 6 100 6 100 Total Action 6 100 6 100 Total Programme 6 100 6 100 Total -

Dekadal Climate Alerts and Probable Impacts for the Period 21St to 30Th November 2020

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix-Travail-Patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland ----------- ----------- OBSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUR NATIONAL OBSERVATORY LES CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES ON CLIMATE CHANGE ----------------- ----------------- DIRECTION GENERALE DIRECTORATE GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- ONACC www.onacc.cm; [email protected]; Tel : (+237) 693 370 504 / 654 392 529 BULLETIN N° 63 Dekadal climate alerts and probable impacts for the period 21st to 30th November 2020 st 21 November 2020 © NOCC November 2020, all rights reserved Supervision Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). Production Team (NOCC) Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). BATHA Romain Armand Soleil, PhD student and Technical staff, NOCC. ZOUH TEM Isabella, M.Sc. in GIS-Environment and Technical staff, NOCC. NDJELA MBEIH Gaston Evarice, M.Sc. in Economics and Environmental Management. MEYONG René Ramsès, M.Sc. in Physical Geography (Climatology/Biogeography). ANYE Victorine Ambo, Administrative staff, NOCC. ELONG Julien Aymar, M.Sc. in Business and Environmental law. I. Introduction This dekadal -

How Serious Is Corruption in the Non-Wood Forest Products

Transparency and governance in non-wood forest product commodity chains, an example from Cameroon: a need to include NWFP in the FLEGT mechanism. Julius Chupezi TIEGUHONG1, Ousseynou NDOYE, Sophie GROUWELS, Armand ASSENG ZE, Juliane MASUCH, Ignace Fokou SAKAM and William MALA 1Email: [email protected] & [email protected]; Tel: +237 75622222 Fax: +237 22204811 At the World Forestry Congresses (WFC) in 2003 and 2009, good governance and efficient institutions were reiterated as necessary indicators to consider when measuring positive outcomes resulting from long-term thinking in the forest discourse at all levels. It was further stressed that without good governance and effective institutions, the scope of sustainable forest management will remain limited. This discourse dwells on concepts such as democratisation, accountability, empowerment, equity, corruption, illegality, governance and transparency. Examined in this paper are the practical applications of four of the latter interrelated concepts as they relate to the production, transportation and trade of non-wood forest products, and looking specifically at a case study on Gnetum spp, a leafy vegetable in Cameroon. Data was collected from traders on all of the financial transactions involved in accessing, transporting and selling Gnetum spp from the zone of production to the point of export over a period of one year. A total of 18368 transactions were documented during 302 journeys. 81.6% of the transactions were illegal but covered 33.5% of the total costs of all transactions (341 250 960 CFAF equivalent to US$ 780558) over the study period. There were a total of 122 locations and major reasons for making a financial transaction with only 10.7% that covered legal transactions while 65.6% covered completely illegal transactions and 23.7% both legal and illegal transactions. -

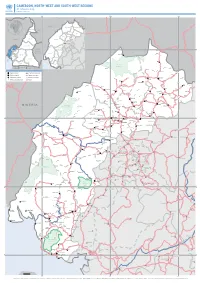

CAMEROON, NORTH-WEST and SOUTH-WEST REGIONS A1 Reference Map Update of June 2018

CAMEROON, NORTH-WEST AND SOUTH-WEST REGIONS A1 reference map Update of June 2018 9.0°E 10.0°E 11.0°E NIGERIA DONGA-MANTUNG EXTRÊME-NORD MENCHUMMENCHUM DONGA-MANTUNG FAR-NORTH CHAD BOYO BOYO BUIBUI MEZAM NGO- MOMOMOMO MEZAM NGOKETUNJIA-KETUNJIA NORTHNORD NIGERIA MANYUMANYU LEBIALEMLEBIALEM ADAMAOUAADAMAOUA NORTH- KUPE- 7.0°N NORD-OUEST-WEST CENTRAL -MUANENGUBA KUPE-MUANENGUBA Abonshie WESTOUEST AFRICAN SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC -WEST NDIANNDIAN Buku CENTRECENTRE Furu Awa LITTORALLITTORAL MEMEMEME EASTEST Ako SOUTHSUD FAKOFAKO Kimbi-Fungom EQ. Natianal Park GABON Akwaja GUINEA CONGO Munkep Dumbu Adere Ande Jevi Berabe Region capital International border Lus Kom Division capital Region boundary Subdivision capital Division boundary Abar NKAMBE Mfom Esu Misaje Ntong Other populated place Road Binka Iyahe Zhoa Akumaye Baworo Fonfuka Gom Ballin Nwa Yang Weh Kumfutu Mbwat Benade Lassin Ngale Ndu Benakuma Rom Benagudi Konene WUM Kuk Nkor Akwaya Sabongari Mmen Tatum Ntumbaw Modelle Aduk Ngu Nkim Assaka Ajung Befang Ntem Bu Tinta FUNDONG Mbonso Mbenkas Elak Shishong Njinikom Obang Dzeng Takamanda Mbakong KUMBO NIGERIA Mbiame Nskumba Ayi Mejang Natianal Park Tingoh Belo Ote Njikwa Oshie Babanki Ibal Tava Ngwo Tugi Bafut Jakiri Babungo Akwa Akanunku Tinachong Lip Bambui Sabga 6.0°N Mbu MBENGWI Baba I Babessi Dadi Menka Bambili NDOP 6.0°N Andek Kajifu Acha Tugui Mankon Nkwen Nyang Bamessing Bangolan Magba Ebinsi Teze Abebung BAMENDA Olorunti Kai Bangourain Akum Bambalang Oshum Balikumbat Agborkem Widikum Bali Mukoyong Bamukumbit Baliben Njimom Batibo