How Serious Is Corruption in the Non-Wood Forest Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINMAP Région Du Centre SERVICES DECONCENTRES REGIONAUX ET DEPARTEMENTAUX

MINMAP Région du Centre SERVICES DECONCENTRES REGIONAUX ET DEPARTEMENTAUX N° Désignation des MO/MOD Nbre de Marchés Montant des Marchés N° page 1 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 19 2 278 252 000 4 Département de la Haute Sanaga 2 Services déconcentrés départementaux 6 291 434 000 7 3 COMMUNE DE BIBEY 2 77 000 000 8 4 COMMUNE DE LEMBE YEZOUM 8 119 000 000 8 5 COMMUNE DE MBANDJOCK 3 50 000 000 10 6 COMMUNE DE MINTA 5 152 500 000 10 7 COMMUNE DE NANGA-EBOKO 12 139 500 000 11 8 COMMUNE DE NKOTENG 5 76 000 000 13 9 COMMUNE DE NSEM 1 27 000 000 13 TOTAL 42 932 434 000 Département de la Lekié 10 Services déconcentrés départementaux 8 268 357 000 14 11 COMMUNE DE BATCHENGA 2 35 000 000 15 12 COMMUNE DE LOBO 8 247 000 000 15 13 COMMUNE DE MONATELE 11 171 500 000 16 14 COMMUNE DE SA'A 16 384 357 000 18 15 COMMUNE D'ELIG-MFOMO 7 125 000 000 20 16 COMMUNE D'EVODOULA 9 166 250 000 21 17 COMMUNE D'OBALA 14 223 500 000 22 18 COMMUNE D'OKOLA 22 752 956 000 24 19 COMMUNE D’EBEBDA 6 93 000 000 27 TOTAL 103 2 466 920 000 Département du Mbam et Inoubou 20 Services déconcentrés départementaux 4 86 000 000 28 21 COMMUNE DE BAFIA 5 75 500 000 28 22 COMMUNE DE BOKITO 12 213 000 000 29 23 COMMUNE DE KIIKI 4 134 000 000 31 24 COMMUNE DE KONYAMBETA 6 155 000 000 32 25 COMMUNE DE DEUK 2 77 000 000 33 26 COMMUNE DE MAKENENE 3 17 000 000 33 27 COMMUNE DE NDIKINIMEKI 4 84 000 000 34 28 COMMUNE D'OMBESSA 5 91 000 000 34 29 COMMUNE DE NITOUKOU 6 83 000 000 35 TOTAL 51 1 015 500 000 MINMAP/DIVISION DE LA PROGRAMMATION ET DU SUIVI DES MARCHES PUBLICS Page 1 de 88 N° Désignation -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Nyong Et Kellé

OFFICE 3j;E LA RECHERCHE REPUBLIQUE FEDERALE SCIEhTBFIQUE ET TECHNIQUE DU OUTRE-MER CAMEROUN CENTRE ORSTOM DE YAOUNDE DICTIO..NN,AIREDES VILLAGES DU NYONG ET KELLE (2' 6dition) D'après la documentation réuriie par la Sectioiî de Géographie de I'ORSTOM1 REPERTOIRE GEOÇRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN FASCICULE No 8 SH. nu 57 Avril 1970 REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHlQUE DU CAMEROUN Fasc. I Tableau de Io population du Cameroun, 68 p. Fév. 1965 SH. NO 17 Fasc. 2 Dictionnaire des villages du Dia-et-Lobo, 89 p. Juin 1965 SH. NO 22 Fasc. 3 Dictionnaire des villages de la Haute-Sanaga, 44 p. Août 1965 SH. No 50 (2' éd. 1969 1 ' Fasc. 4 Dictionnaire des vtllages du Nyong-et-Mfoumou, 49 p. Oct'obre 1965 SH. NO 24 Fasc. 5 Dictionnaire d,es villages du Nyon;-etspo 45 p. Novembre t965 SH. No 25 Fasc. 6 Dictionneire. des villages du Ntsm 102 p. WC. 1965. SH. NO46 (2' édition Juin 1969 1 d 1% Fasc. 7 ~ictionnair. der village; de la Mefou 100; P. Jahvier 1966 SH. NOk7 1 1 1 , Fasc. 8 Dictionnaire des iillagei du Nyong-et-Ksllé, 5 1 p. Fév: 1b66 SH. 5712' éd. avril 1970 1 1 Fasc. 9 Dictionnsire ;des villages de la Lékié 7 1 p. Merr 1966~~.29. Fasc. 10 ~iction&re des villages de Kr*i 29 p. \ Man- 1965SH. Irp W (2' Bdit. octobre 1969 1 ' 5 ' , Fasc. I I Dictionnaire;diss vlllsg~sdu Mba.r(--60 p. %i 1966 Sç-! W 52 t2' édit. sept. 1969) 1 l Fasc. 12 Dictionnaire de* vfllqgbr de BQU~~~-N~O~O34 p. -

Minmap Region Du Littoral Synthese Des Donnees Sur La Base Des Informations Recueillies

MINMAP REGION DU LITTORAL SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° page Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine de de Douala 94 89 179 421 671 3 2 Communité Urbaine d'édéa 5 89 000 000 14 3 Communité Urbaine de Nkongsamba 6 198 774 344 15 4 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 17 718 555 000 16 Département du Moungo 5 Services déconcentrés départementaux 5 145 000 000 18 6 Commune de BARE BAKEM 2 57 000 000 18 7 Commune de BONALEA 3 85 500 000 19 8 Commune de DIBOMBARI 3 105 500 000 19 9 Commune de LOUM 16 445 395 149 19 10 Commune de MANJO 8 132 000 000 21 11 Commune de MBANGA 3 108 000 000 22 12 Commune de MELONG 12 173 500 000 22 13 Commune de NJOMBE PENJA 5 132 000 000 24 14 Commune d'EBONE 12 299 500 000 25 15 Commune de MOMBO 3 77 000 000 26 16 Commune de NKONGSAMBA I 1 27 000 000 26 17 Commune de NKONGSAMBA II 3 59 250 000 27 18 Commune de NKONGSAMBA III 2 87 000 000 27 TOTAL Département 78 1 933 645 149 Département du Nkam 19 Services déconcentrés départementaux 12 232 596 000 28 20 Commune de NKONDJOCK 16 258 623 000 29 21 Commune de YABASSI 14 221 000 000 31 22 Commune de YINGUI 4 53 500 000 33 23 Commune de NDOBIAN 17 345 418 000 33 TOTAL Département 63 1 111 137 000 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 24 Services déconcentrés départementaux 8 90 960 000 36 25 Commune de Dibamba 3 72 000 000 37 26 Commune de Dizangue 5 88 500 000 37 27 Commune de MASSOCK 4 233 230 000 38 28 Commune de MOUANKO 15 582 770 000 38 29 Commune de NDOM 12 339 237 000 40 Nbre de N° Désignation -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Mbam P

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE REPUBliQUE FEDERALE SCIENTIFIQUE ET TECHNIQUE DU OUT,RE·MER CAMEROUN CENTRE OR5TOM DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES _VILLAGES DU MBAM D'après la documentation réunie par ~la Section de Géographie de l'I.R.CAM.3 REPERTQIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN FASCICULE n° 1 1 rR-GAM 8. P. '9J SH. n° 31 YAOUNDÉ Mai 1966 REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN Fasc. Tableau de la population du Cameroun, 68 p. Fév. 1965 SH, N° 17 Fasc. 2 Dictionnaire des villages du Dia et Lobo, 89 p. Juin 1965 SH. N° 22 Fasc. 3 Dictionnaire des villages de la Haute-Sanaga, 53 p. Août 1965 SH. N° 23 Fasc. 4 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Mfoumou, 49 p. Octobre 1965 SH. N° 24 Fasc. 5 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Soo 45 p. Novembre 1965 SH. N° 25 Fasc. 6 Dictionnaire des villages du Ntem 126 p. Décembre 1965 SH. N° 26 Fasc. 7 Dictionnaire- des villages de la Mefou 108 p. Janvier 1966 SH. N° 27 Fasc. 8 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Kellé 51 p. Février 1966 SH. N° 28 Fasc. 9 Dictionnaire des villages de la Lékié 71 p. Mars 1966 SH. N° 29 Fasc. 10 Dictionnaire des villages de Kribi P. Mars 1966 SH. N° 30 Fasc. 11 Dictionnaire des villages du Mbam P. 60 Mai 1966 SH. N° 31 Fasc. 12 Dictionnaire des villages de Boumba Ngoko (en préparation) Fasc. 13 ùictionnaire des villages de Lom-et-Diérem (en préparation! omCE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE RERJBLlQUE FEDERALE ET TECHNI~E OUmE-MER ID CAMEROUN _ • _cee- -- - CENTRE ORSTOM DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE ~ VILLAGES DU ...........M B A M MAI 1!66 S.R. -

Dictionnaire Des Villages De La Haute Sanaga a Été Entièrement Remise À Jour Et Corrigée En Fonction Des Derniers Renseignements Que Nous Possédons

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE REPUBLIQUE FEDEIlA~ SCIENTIFIQUE ET TECHNIQUE DU OUTRE-MER CAMEROUN CENTRE ORSTOM DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIR'E DES VILLAGES DE LA HAUTE SANAGA (2ème Editan) ~aprèS la documentation réunie ~-:-l ~ection de Géographie de l' ORST~ "~fUTOJkGEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN FASCICULE N° 3 B. P. 193 SH. n° 50 YAOUNDE Août 1968 REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN Fasc. Tableau de la population du Cameroun, 68 p. Fév. 1965 SH. N° 17 Fasc. 2 Dictionnaire des villages du Dia et lobo, 89 p. Juin 1965 SH. N° 22 Fasc. 3 Dictionnaire des villages de la Haute-Sanaga, 44 p. Août 1968 SH. N° 50 (2éme édition) Fasc. 4 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Mfoumou, 49 p. Octobre 1965 SH. N° 24 ~: Fasc. 5 Dictio~riaire des villages du Nyong et Soo 45 p. Novembre 1965 SH. N° 25 Fasc. 6 Dictionnaire des villages du Ntem 102 p. Juin 1968 SH. N° 46 (2ème édition) Fasc. 7 Dictionnaire des villages de la Mefou 108 p. Janvier 1966 SH. N° 27 Fa sc. 8 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Kellé 51 p. Février 1966 SH. N° 28 Fa sc. 9 Dictionnaire des villages de la lékié 71 p. Mars 1966 SH. N° 29 Fasc. 10 Dictionnaire des villages de Kribi P. Mars 1966 SH. N° 30 Fasc. 11 Dictionnaire des villages du Mbam 60 P. Mai 1966 SH. N° 31 Fasc. 12 Dictionnaire des villages de Boumba Ngoko 34 p. Juin 1966 SH. 39 Fasc. 13 Dictionnaire des villages de lom-et-Djérem 35 p. Juillet 1967 SH. 40 Fasc. 14 Dictionnaire des villages de la Kadei 52 p. -

Approved by the Ministry of the Environment and Forests

Project of Independent Observation in Support of Forest Law Enforcement in Cameroon Approved by the Ministry of the Environment and Forests Report No. 027 En Joint Mission: Central Control Unit – Independent Observer ------------------------------- Title: None Location: Central Province Mission date: September 20-21, 2002 Company: GCI Nyanzom, IBC Independent Observer (Global Witness): Mr. Stuart Wilson, Project Director Mr. Owada Jean Cyrille, Technical Assistant Mr. Tangyie Ché Célestine, Driver TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. 1 2. RESOURCES USED ............................................................................................. 2 3. COMPOSITION OF THE MISSION................................................................ 2 4. CONSTRAINTS ..................................................................................................... 2 5. RESULTS OF THE MISSION............................................................................ 2 5.1. Summary of the case ............................................................................................. 2 5.2. Meetings with IBC representatives and various external services representatives 2 5.3. Official hearing of the Ombessa forest law enforcement official ......................... 3 6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS......................................... 4 Appendix ......................................................................................................................... -

Evidence of Iron Mineralization Channels in the Messondo Area (Centre-Cameroon) Using Geoelectrical (DC & IP) Methods: a Case Study

International Journal of Geosciences, 2014, 5, 346-361 Published Online March 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ijg http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijg.2014.53034 Evidence of Iron Mineralization Channels in the Messondo Area (Centre-Cameroon) Using Geoelectrical (DC & IP) Methods: A Case Study Ngoumou Paul Claude1, Ndougsa-Mbarga Théophile2*, Assembe Stéphane Patrick1, Kofane Timoleon Crepin1 1Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé, Cameroon 2Department of Physics Advanced Teachers’ Training College, University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé, Cameroon Email: *[email protected] Received 1 April 2013; revised 2 May 2013; accepted 4 June 2013 Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract A geophysical survey was conducted in the Kelle-Bidjocka village, Messondo subdivision, in the Centre Region, Cameroon. The data acquisition was made by combining Schlumberger profiling and electrical soundings along six (06) profiles of 1500 m in length for a total of 64 geoelectrical stations’ survey conducted through a variable mesh 100 m × 200 m, or 100 m × 300 m. The equipment used is the DC resistivimeter Syscal Junior 48 (Iris Instrument). Processing and model- ling of field data are made by using the Res2Dinv, Qwseln and Surfer software. The investigation methods used are electrical resistivity (DC) and induced polarization (IP) methods. The analyses and interpretations have helped to highlight areas of weakness or conductive discontinuities (fractures, faults, shear zones, etc.) in Precambrian gneiss formations, sometimes undergoing weathering processes. -

Joshua Osih President

Joshua Osih President THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 2018 JOSHUA OSIH | THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY | P . 1 MY CONTRACT WITH THE NATION Build a new Cameroon through determination, duty to act and innovation! I decided to run in the presidential election of October 7th to give the youth, who constitute the vast majority of our population, the opportunity to escape the despair that has gripped them for more than three decades now, to finally assume responsibility for the future direction of our highly endowed nation. The time has come for our youth to rise in their numbers in unison and take control of their destiny and stop the I have decided to run in the presidential nation’s descent into the abyss. They election on October 7th. This decision, must and can put Cameroon back on taken after a great deal of thought, the tracks of progress. Thirty-six years arose from several challenges we of selfish rule by an irresponsible have all faced. These crystalized into and corrupt regime have brought an a single resolution: We must redeem otherwise prosperous Cameroonian Cameroon from the abyss of thirty-six nation to its knees. The very basic years of low performance, curb the elements of statecraft have all but negative instinct of conserving power disappeared and the citizenry is at all cost and save the collapsing caught in a maelstrom. As a nation, system from further degradation. I we can no longer afford adequate have therefore been moved to run medical treatment, nor can we provide for in the presidential election of quality education for our children. -

Programmation De La Passation Et De L'exécution Des Marchés Publics

PROGRAMMATION DE LA PASSATION ET DE L’EXÉCUTION DES MARCHÉS PUBLICS EXERCICE 2021 JOURNAUX DE PROGRAMMATION DES MARCHÉS DES SERVICES DÉCONCENTRÉS ET DES COLLECTIVITÉS TERRITORIALES DÉCENTRALISÉES RÉGION DU CENTRE EXERCICE 2021 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES N° Désignation des MO/MOD Nbre de Marchés Montant des Marchés N°Page 1 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 17 736 645 000 3 2 Communauté Urbaine de Yaoundé 62 10 459 000 000 5 Département de la Haute Sanaga 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 2 24 000 000 10 4 Commune de Bibey 12 389 810 000 10 5 Commune de Lembe Yezoum 17 397 610 000 11 6 Commune de Mbandjock 12 214 000 000 12 7 Commune de Minta 8 184 500 000 12 8 Commune de Nanga Ebogo 21 372 860 000 13 9 Commune de Nkoteng 12 281 550 000 14 10 Commune de Nsem 5 158 050 000 15 TOTAL 89 2 022 380 000 Département de la Lekié 11 Services déconcentrés départementaux 9 427 000 000 16 12 Commune de Batchenga 8 194 000 000 17 13 Commune d'Ebebda 10 218 150 000 18 14 Commune d'Elig-Mfomo 8 174 000 000 19 15 Commune d'Evodoula 10 242 531 952 20 16 Commune de Lobo 11 512 809 000 21 17 Commune de Monatélé 12 288 500 000 22 18 commune d'Obala 11 147 000 000 23 19 commune d'Okola 14 363 657 000 24 20 commune de Sa'a 17 319 500 000 25 TOTAL 110 2 887 147 952 Département du Mbam et Inoubou 21 Services déconcentrés départementaux 6 144 385 000 27 22 Commune Bafia 13 213 500 000 27 23 Commune de Bokito 9 167 500 000 28 24 Commune de DEUK 17 379 500 000 29 25 Commune Kiiki 10 285 000 000 30 26 Commune Konyambeta 12 295 -

Cholera Outbreak

Emergency appeal final report Cameroon: Cholera outbreak Emergency appeal n° MDRCM011 GLIDE n° EP-2011-000034-CMR 31 October 2012 Period covered by this Final Report: 04 April 2011 to 30 June 2012 Appeal target (current): CHF 1,361,331. Appeal coverage: 21%; <click here to go directly to the final financial report, or here to view the contact details> Appeal history: This Emergency Appeal was initially launched on 04 April 2011 for CHF 1,249,847 for 12 months to assist 87,500 beneficiaries. CHF 150,000 was initially allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the national society in responding by delivering assistance. Operations update No 1 was issued on 30 May 2011 to revise the objectives and budget of the operation. Operations update No 2 was issued on 31st May 2011 to provide financial statement against revised budget. Operations update No 3 was issued on 12 October 2011 to summarize the achievements 6 months into the operation. Operations update No 4 was issued on 29 February 2012 to extend the timeframe of the operation from 31st March to 30 June 2012 to cover the funding agreement with the American Embassy in Cameroon. PBR No M1111087 was submitted as final report of this operation to the American Embassy in Cameroon on 03 August 2012. Throughout the operation, Cameroon Red Cross volunteers sensitized the populations on PBR No M1111127 was submitted as final report of this how to avoid cholera. Photo/IFRC operation to the British Red Cross on 14 August 2012. Summary: A serious cholera epidemic affected Cameroon since 2010. -

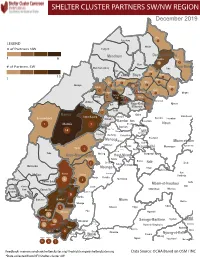

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Project : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2

PROJECT : TRANSPORT SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMME PHASE 2 COUNTRY : REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Joseph Kouassi N’GUESSAN, OITC.1/CMFO Chief Transport Engineer Jean-Pierre KALALA, Chief OITC1/CDFO Socio-Economist Modeste KINANE, Principal ONEC.3 Environmentalist Jean Paterne MEGNE EKOGA, OITC.1 Team Members Senior Transport Economist Project Samuel MBA, Senior Transport OSHD.2/CMFO Team Engineer S. KEITA, Principal Financial OITC1 Management Specialist C. DJEUFO, Procurement ONEC.3 Specialist Sector Division Manager J. K. KABANGUKA OITC.1 Resident Representative R. KANE CMFO Sector Director A. OUMAROU OITC Regional Director M. KANGA ORCE SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Programme Name : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 SAP Code: P-CM-DB0-015 Country : Cameroon Department : OITC Division : OITC-1 1. INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 which involves the execution of works on the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Bamenda road. The impact assessment of the project was conducted in 2012. This assessment seeks to harmonize and update the previous one conducted in 2012. According to national regulations, the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Babadjou road section rehabilitation project is one of the activities that require the conduct of a full environmental and social impact assessment. This project has been classified under Environmental Category 1 in accordance with the African Development Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) of July 2014. This summary has been prepared in accordance with AfDB’s environmental and social impact assessment guidelines and procedures for Category 1 projects.