Zahir Shah's Cabinet, Afghanistan 1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Nouvelles D'afghanistan

Trente-troisième année N°139 Décembre 2012 (4ème trimestre) 6 Euros Les Nouvelles d’AFGHANISTAN spécial ISSN 0249-0072 ISSN Afghanistan-Pakistan Editorial Les Nouvelles d’Afghanistan SOMMAIRE N°139 Afghanistan et Pakistan deux destins indissociables d’une histoire commune Dépasser les malentendus par Pierre LAFRANCE 3 Pourquoi tant d’acharnement ? par Zia FARHANG 12 On sait qu’une des clefs du problème afghan se trouve au Pakistan. Nous Les ambitions du Pakistan en Afghanistan avons donc décidé d’ouvrir dans ce numéro le dossier des relations entre le par Homayoun Chah ASSEFY 15 Pakistan et l’Afghanistan. Dossier bien délicat. Pierre Lafrance montre dans son étude approfondie de la préhistoire de ces relations, combien les siècles La Ligne Durand par Léa MÉRILLON 18 ont fait bouger les peuples et les dynasties, au point que Pakistan et Afghanis- tan sont héritiers d’une histoire commune, tout en se disputant une partie de Survol des relations économiques cet héritage. Ah qu’il est difficile d’être frères sur des terres si voisines ! afghano-pakistanaises Notre dossier n’épuise pas le sujet. Bien d’autres aspects auraient pu être par Daood MOOSA 20 étudiés : par exemple les relations entre tribus pachtouns des deux côtés de la Les relations indo-pakistanaises frontière. Certes, la ligne Durand est le fait d’un arbitraire colonial. Mais il serait et l’Afghanistan intéressant d’étudier s’il y a des différences entre les Pachtouns d’Afghanistan par Olivier BLAREL 23 et ceux qu’on appelle Pathans côté pakistanais. Nous pourrons compléter ce dossier dans nos numéros à venir. -

Hadith and Its Principles in the Early Days of Islam

HADITH AND ITS PRINCIPLES IN THE EARLY DAYS OF ISLAM A CRITICAL STUDY OF A WESTERN APPROACH FATHIDDIN BEYANOUNI DEPARTMENT OF ARABIC AND ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Glasgow 1994. © Fathiddin Beyanouni, 1994. ProQuest Number: 11007846 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007846 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 M t&e name of &Jla&, Most ©racious, Most iKlercifuI “go take to&at tfje iHessenaer aikes you, an& refrain from to&at tie pro&tfuts you. &nO fear gJtati: for aft is strict in ftunis&ment”. ©Ut. It*. 7. CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................4 Abbreviations................................................................................................................ 5 Key to transliteration....................................................................6 A bstract............................................................................................................................7 -

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

SSC-SUPPL-2018-RESULT.Pdf

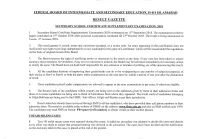

FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 1 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 SALIENT FEATURES OF RESULT ALL AREAS G r a d e W i s e D i s t r i b u t i o n Pass Sts. / Grp. / Gender Enrolled Absent Appd. R.L. UFM Fail Pass A1 A B C D E %age G.P.A EX/PRIVATE CANDIDATES Male 6965 132 6833 16 5 3587 3241 97 112 230 1154 1585 56 47.43 1.28 Female 2161 47 2114 12 1 893 1220 73 63 117 625 335 7 57.71 1.78 1 SCIENCE Total : 9126 179 8947 28 6 4480 4461 170 175 347 1779 1920 63 49.86 1.40 Male 1086 39 1047 2 1 794 252 0 2 7 37 159 45 24.07 0.49 Female 1019 22 997 4 3 614 380 1 0 18 127 217 16 38.11 0.91 2 HUMANITIES Total : 2105 61 2044 6 4 1408 632 1 2 25 164 376 61 30.92 0.70 Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 Grand Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 2 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE GAZETTE Subjects EHE:I ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - I PST-II PAKISTAN STUDIES - II (HIC) AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I EHE:II ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - II U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I (HIC) F-N:I FOOD AND NUTRITION - I U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I (HIC) AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II F-N:II FOOD AND NUTRITION - II U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II (HIC) G-M:I MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - I U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II (HIC) ARB:I ARABIC - I G-M:II MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - II U-S URDU SALEES (IN LIEU OF URDU II) ARB:II ARABIC - II G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I WEL:I WELDING (ARC & GAS) - I BIO:I BIOLOGY - I G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I (HIC) WEL:II WELDING (ARC AND GAS) - II BIO:II BIOLOGY - II G-S:II GENERAL SCIENCE - II WWF:I WOOD WORKING AND FUR. -

The Cooperation Between China and Afghanistan Under the “Belt and Road Initiative”

International Relations and Diplomacy, June 2018, Vol. 6, No. 6, 359-368 doi: 10.17265/2328-2134/2018.06.005 DDAVID PUBLISHING The Cooperation Between China and Afghanistan Under the “Belt and Road Initiative” YAN Wei Northwest University, Shaanxi, China Afghanistan is a neighboring country to China. The Afghanistan issue has had an important impact on China’s national security. Since the establishment of the new Afghan government in 2001, China has been committed to promoting Afghanistan’s economic, social, and security reconstruction, and has invested heavily resources in Afghanistan’s reconstruction. The main cause of the Afghan problem is that the Afghan government lacked enough resources and can only rely on the foreign powers’ aids. Afghanistan eventually loses its independence, and triggers interference in big powers. At present, Afghanistan still has not escaped this predicament. Near 50% of the Afghan government’s revenue comes from foreign aids. In 2013, the “Belt and Road Initiative” proposed by China provided opportunity for the reconstruction of Afghanistan. Afghanistan, as the crossroads of the land Silk Road and the heart of Asia, has become more prominent in its geopolitical status for “Belt and Road Initiative”. By participating “Belt and Road Initiative”, Afghanistan can help to activate its own economic vitality and promote the cross-border trade. It has changed the situation that Afghanistan is highly dependent on external aids. This helps to solve the problems of reconstruction in Afghanistan. Keywords: China, Afghanistan, Belt and Road Initiative The Rise of Afghan Problem: From the Cross of Silk Road to Buffer State From a geographic perspective, Afghanistan is a crossroads of Asia (Carter, 1989) and the hub of the ancient Silk Road. -

418338 1 En Bookbackmatter 205..225

Glossary Abhayamudra A style of keeping hands while sitting Abhidhama The Abhidhamma Pitaka is a detailed scholastic reworking of material appearing in the Suttas, according to schematic classifications. It does not contain systematic philosophical treatises, but summaries or enumerated lists. The other two collections are the Sutta Pitaka and the Vinaya Pitaka Abhog It is the fourth part of a composition. The last movement gradually goes back to the sthayi after completion of the paraphrasing and improvisation of the composition, which can cover even three octaves in the recital of a master performer Acharya A teacher or a tutor who is the symbol of wisdom Addhayoga One of seven kinds of lodgings where monks are allowed to live. Addhayoga is a building with a roof sloping on either one side or both. It is shaped like wings of the Garuda Agganna-sutta AggannaSutta is the 27th Sutta of the Digha Nikaya collection. The sutta describes a discourse imparted by the Buddha to two Brahmins, Bharadvaja, and Vasettha, who left their family and caste to become monks Ahankar Haughtiness, self-importance A-hlu-khan mandap Burmese term, a temporary pavilion to receive donation Akshamala A japa mala or mala (meaning garland) which is a string of prayer beads commonly used by Hindus, Buddhists, and some Sikhs for the spiritual practice known in Sanskrit as japa. It is usually made from 108 beads, though other numbers may also be used Amulets An ornament or small piece of jewellery thought to give protection against evil, danger, or disease. Clay tablets have also been used as amulets. -

Afghan Internationalism and the Question of Afghanistan's Political Legitimacy

This is a repository copy of Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan's political legitimacy. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/126847/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Leake, E orcid.org/0000-0003-1277-580X (2018) Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan's political legitimacy. Afghanistan, 1 (1). pp. 68-94. ISSN 2399-357X https://doi.org/10.3366/afg.2018.0006 This article is protected by copyright. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Edinburgh University Press on behalf of the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies in "Afghanistan". Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan’s political legitimacy1 Abstract This article uses Afghan engagement with twentieth-century international politics to reflect on the fluctuating nature of Afghan statehood and citizenship, with a particular focus on Afghanistan’s political ‘revolutions’ in 1973 and 1978. -

Emperor Of! Japan Pm Zahir Watches "Inspecter

' ' V.I Hi- ; ' KABIRI & CO. LTD NAWROZ CARPET 'A n Biggest exporters of Afghan EXPORT CO, s t; PHi rri handicrafts offering' the best quality Afghan products at: displays highest quality newold H rugs, genuine antlqae arms, po. Ac n osteenchas and ' other Afghan iahlR tbuTIQtE: ' ' ' Address; ::Charahi '.Ansarl (Share handicrafts: . v A A r:AA's A Address: Share Nau opposite h.!u;i v i 30189 '.":!"30183. Blue Mosque . J -- "'";.-- . Teh: and ? .( , n If '..''i''"'"-.- I Post Box; .406. Tela: 32035 and 31051. AA Cable. PUST1NCHA Cable: Nawroz-Kabul- . VOL. XN0.125 KABUL, THURSDAY, AUGUST 19, 1971 (ASAP 28, 1350 PRICE AF. 4 HM SENDS Royal audience ; " ' KABUL, Augv 'ig;;. '(Bakhitar) . p MESSAGE TO During' the ' week ending to--(2 I'! dajf, (Hrs'esty the received, in audience, the foll-- v EMPEROR owing,, according to a Royal if 4 ft-- ; 'I Protocol Depaijtmen(t (announ-- OF! JAPAN cement: ; Senate President Abdul Hadi . K i KABUL, Aug. 19, (BMakhtar). , , Dawi.' National Defence Mi-- - friendly . message t from v y r histet General' Khan Moham-- i Ills Majesty the King of Afgba mad, ' Interior MjAister 1 Aman-- ; nistan was presented to the ullah ' Mansuri, Justice wMinis-- Emperor of Japan last week. a Argha-- , ter Mohammad Anwar f aa presentation Minis-te- r, The was made , . ndiwal,; .Public, Works v, by the Afghan Ambassador to Gen. Khwazak Zamai, Mi-- A Tokyo, .. Sayed Kassem Rlshtya, nister,. portfolio,. j, Mrs. 4 without ' through . ' ' the Minister of State . Shafiqa Ziayee,; minister with- - and acting Foreign Minister, ';iout portfolio Abdul ' Sattar" Si- - ' ';: Toshio Kimufa, , ,. , ' i rat, Justice Dr. -

Cyrtopodion Baturense (Khan and Baig 1992) and Cyrtopodion Walli (Ingoldby 1922) (Sauria: Gekkonidae)

Zootaxa 2636: 1–20 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Studies on Pakistan Lizards: Cyrtopodion baturense (Khan and Baig 1992) and Cyrtopodion walli (Ingoldby 1922) (Sauria: Gekkonidae) KURT AUFFENBERG1,4, KENNETH L. KRYSKO2 & HAFIZUR REHMAN3 1Florida Museum of Natural History, Powell Hall, P. O. Box 112710, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Florida Museum of Natural History, Division of Herpetology, P.O. Box 117800, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 3Zoological Survey Department, Government of Pakistan, Karachi 72400 Pakistan 4Corresponding author Abstract The taxonomy of Eurasian angular or thin-toed geckos has undergone a great deal of revision over the last 30 years. However, it is clear that a desirable level of taxonomic resolution has not yet been attained as their taxonomic assignments are somewhat arbitrary. In this paper, we discuss two lesser-known gecko species, Cyrtopodion baturense (Khan and Baig 1992) and C. walli (Ingoldby 1922). One adult specimen of Cyrtopodion baturense (the only known specimen other than the type series) and a series of 53 C. walli collected by Walter Auffenberg and the Zoological Survey Department of Pakistan (ZSD) and subsequently deposited in the University of Florida Herpetology collection were compared to the type specimens. Specimens were examined for 46 morphological characters and measurements. Cyrtopodion baturense and C. walli are diagnosable and confirmed to be distinct species. Cyrtopodion baturense is known only from the holotype locality of Pasu and the nearby village of Dih, Hunza District, in the Gilgit Agency, Federally Administered Northern Areas (FANA), Pakistan, at 2,438–3,078 m elevations. -

Turkomans Between Two Empires

TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) A Ph.D. Dissertation by RIZA YILDIRIM Department of History Bilkent University Ankara February 2008 To Sufis of Lāhijan TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by RIZA YILDIRIM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA February 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Oktay Özel Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Halil Đnalcık Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Yaşar Ocak Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Evgeni Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan

A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF KING AMANULLAH KHAN DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iJlajSttr of ^Ijiloioplip IN 3 *Kr HISTORY • I. BY MD. WASEEM RAJA UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. R. K. TRIVEDI READER CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDU) 1996 J :^ ... \ . fiCC i^'-'-. DS3004 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY r.u Ko„ „ S External ; 40 0 146 I Internal : 3 4 1 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSTTY M.IGARH—202 002 fU.P.). INDIA 15 October, 1996 This is to certify that the dissertation on "A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan", submitted by Mr. Waseem Raja is the original work of the candidate and is suitable for submission for the award of M.Phil, degree. 1 /• <^:. C^\ VVv K' DR. Rij KUMAR TRIVEDI Supervisor. DEDICATED TO MY DEAREST MOTHER CONTENTS CHAPTERS PAGE NO. Acknowledgement i - iii Introduction iv - viii I THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE 1-11 II HISTORICAL ANTECEDANTS 12 - 27 III AMANULLAH : EARLY DAYS AND FACTORS INFLUENCING HIS PERSONALITY 28-43 IV AMIR AMANULLAH'S ASSUMING OF POWER AND THE THIRD ANGLO-AFGHAN WAR 44-56 V AMIR AMANULLAH'S REFORM MOVEMENT : EVOLUTION AND CAUSES OF ITS FAILURES 57-76 VI THE KHOST REBELLION OF MARCH 1924 77 - 85 VII AMANULLAH'S GRAND TOUR 86 - 98 VIII THE LAST DAYS : REBELLION AND OUSTER OF AMANULLAH 99 - 118 IX GEOPOLITICS AND DIPLCMIATIC TIES OF AFGHANISTAN WITH THE GREAT BRITAIN, RUSSIA AND GERMANY A) Russio-Afghan Relations during Amanullah's Reign 119 - 129 B) Anglo-Afghan Relations during Amir Amanullah's Reign 130 - 143 C) Response to German interest in Afghanistan 144 - 151 AN ASSESSMENT 152 - 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 - 174 APPENDICES 175 - 185 **** ** ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The successful completion of a work like this it is often difficult to ignore the valuable suggestions, advice and worthy guidance of teachers and scholars. -

Revolutionary Afghanistan Is No Exception

CONTENTS PREFACE 1. In Search of Hafizullah Amin 6 2. Three Revolutionaries 12 3. A House Divided: the PDPA, 1965-1973 25 4. The Making of a Revolution: the PDPA, 1973-1978 39 5. The Inheritance: Afghanistan, 1978 53 6. Strategy for Reform 88 7. The Eid Conspiracy 106 8. A Treaty and a Murder: Closing the American Option 120 9. The Question of Leadership 133 10. The Summer of Discontent 147 11. The End Game 166 12. ‘. And the People Remain’ 186 Select Bibliography 190 PREFACE PREFACE The idea for this book arose from a visit to Kabul in March 1979 when it became immediately obvious that what was happening in Afghanistan bore little relation to reports appearing in the Western media. Further research subsequently reinforced that impression. Much of the material on which the book is based was collected in the course of my 1979 field trip which took me to India, Pakistan and the United Kingdom as well as Afghanistan and during a follow-up trip to India and Pakistan from December 1980 to January 1981. Unfortunately by then times had changed and on this second occasion the Afghan government refused me a visa. Texts of speeches and statements by Afghan leaders and other Afghan government documents have for the most part been taken from the Kabul Times, since these are in effect the official version. I have however taken the liberty where necessary of adjusting the syntax of the Afghan translator. The problem of transliteration is inescapable, and at the risk of offending the purists I have chosen what appears to be the simplest spelling of Afghan names and have tried to be consistent.