University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Identity and German Landscapes in Konrad Wolf's I Was Nineteen

Religions 2012, 3, 130–150; doi:10.3390/rel3010130 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Homecoming as a National Founding Myth: Jewish Identity and German Landscapes in Konrad Wolf’s I was Nineteen Ofer Ashkenazi History Department, University of Minnesota, 1110 Heller Hall, 271 19th Ave S, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: 1-651-442-3030 Received: 5 January 2012; in revised form: 13 March 2012 / Accepted: 14 March 2012 / Published: 22 March 2012 Abstract: Konrad Wolf was one of the most enigmatic intellectuals of East Germany. The son of the Jewish Communist playwright Friedrich Wolf and the brother of Markus Wolf— the head of the GDR‘s Foreign Intelligence Agency—Konrad Wolf was exiled in Moscow during the Nazi era and returned to Germany as a Red Army soldier by the end of World War Two. This article examines Wolf‘s 1968 autobiographical film I was Nineteen (Ich war Neunzehn), which narrates the final days of World War II—and the initial formation of postwar reality—from the point of view of an exiled German volunteer in the Soviet Army. In analyzing Wolf‘s portrayals of the German landscape, I argue that he used the audio- visual clichés of Heimat-symbolism in order to undermine the sense of a homogenous and apolitical community commonly associated with this concept. Thrown out of their original contexts, his displaced Heimat images negotiate a sense of a heterogeneous community, which assumes multi-layered identities and highlights the shared ideology rather than the shared origins of the members of the national community. -

January 2012 at BFI Southbank

PRESS RELEASE November 2011 11/77 January 2012 at BFI Southbank Dickens on Screen, Woody Allen & the first London Comedy Film Festival Major Seasons: x Dickens on Screen Charles Dickens (1812-1870) is undoubtedly the greatest-ever English novelist, and as a key contribution to the worldwide celebrations of his 200th birthday – co-ordinated by Film London and The Charles Dickens Museum in partnership with the BFI – BFI Southbank will launch this comprehensive three-month survey of his works adapted for film and television x Wise Cracks: The Comedies of Woody Allen Woody Allen has also made his fair share of serious films, but since this month sees BFI Southbank celebrate the highlights of his peerless career as a writer-director of comedy films; with the inclusion of both Zelig (1983) and the Oscar-winning Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) on Extended Run 30 December - 19 January x Extended Run: L’Atalante (Dir, Jean Vigo, 1934) 20 January – 29 February Funny, heart-rending, erotic, suspenseful, exhilaratingly inventive... Jean Vigo’s only full- length feature satisfies on so many levels, it’s no surprise it’s widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made Featured Events Highlights from our events calendar include: x LoCo presents: The London Comedy Film Festival 26 – 29 January LoCo joins forces with BFI Southbank to present the first London Comedy Film Festival, with features previews, classics, masterclasses and special guests in celebration of the genre x Plus previews of some of the best titles from the BFI London Film Festival: -

Les Films De Valeria Sarmiento ! Ou D’Exposition

GARDIENNE DE LA MÉMOIRE Depuis la disparition de Ruiz, Valeria Sarmiento poursuit le travail du compagnon de sa vie. Elle dirige Les Lignes de Wellington (2012), projet interrompu par la mort du cinéaste où elle esquisse l’art de la guerre à travers la figure du duc de Wellington, commandant en chef des armées portugaise et britannique, un général obsédé par son image. Remodelant le projet initial, elle s’étend sur la manière dont les guerres napoléoniennes bouleversent les géographies – paysages et visages – insistant sur l’empreinte que laisse la guerre dans les rapports entre les hommes. Comme un dernier salut des membres de la « troupe » de Ruiz, certains acteurs viennent rendre hommage (Melvil Poupaud, John Malkovich, Chiara Mastroianni, Michel Piccoli, Catherine Deneuve, Isabelle Huppert), le temps d’une apparition mémorable, au réalisateur. De même, en l’attente de la mise en production de VALERIA SARMIENTO VALERIA son adaptation du roman de Roberto Bolaño (La Piste de glace), Sarmiento dirige Le Cahier noir (2018), une préquelle des Mystères de Lisbonne de Ruiz (2010), laissée à l’état de projet par le scénariste Carlos Saboga. À nouveau, Sarmiento infléchit le feuilleton d’origine, s’écartant de la figure protéiforme d’un cardinal mystérieux pour se concentrer sur les rapports entre le jeune Sebastian et sa nourrice, incarnée par la sensuelle et ardente Lou de Laâge. Mais la réalisatrice intervient aussi comme mémorialiste, sauvegardant et per- mettant la projection des films de Ruiz. Telle Isis en quête du corps d’Osiris, elle remembre certains des très nombreux projets inachevés comme cette Telenovela errante (1990-2017), feuilleton erratique qui enferme en plusieurs sketches les premières impressions, vivaces et drôles, du réalisateur lorsqu’il a pu tourner à PROGRAMMATION Amelia Lopes O’Neill nouveau dans son pays, ou encore son mythique premier film inachevé, El Tango del viudo (Le Tango du veuf, 1967). -

Martin Ritt 19:00 PROVIDENCE - Alain Resnais 21:00 the FAN - Ed Bianchi

Domingo 9 17:00 THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD - Martin Ritt 19:00 PROVIDENCE - Alain Resnais 21:00 THE FAN - Ed Bianchi Lunes 10 CGAC 17:00 L’AVEU - Constantin Costa-Gavras 19:30 L’AMOUR À MORT - Alain Resnais 21:15 THE RAIN PEOPLE - Francis Ford Coppola Martes 11 17:00 A DANDY IN ASPIC - Anthony Mann, Laurence Harvey 19:00 THE DEADLY AFFAIR - Sidney Lumet 21:00 DER HIMMEL ÜBER BERLIN - Wim Wenders Miércoles 12 16:30 SECHSE KOMMEN DURCH DIE WELT - Rainer Simon 18:00 TILL EULENSPIEGEL - Rainer Simon 19:45 JADUP UND BOEL - Rainer Simon 21:30 DIE FRAU UND DER FREMDE - Rainer Simon Jueves 13 17:45 WENGLER & SÖHNE, EINE LEGENDE - Rainer Simon 19:30 DER FALL Ö - Rainer Simon 21:15 WORK IN PROGRESS: CORTOMETRAJES DE MARCOS NINE - Marcos Nine Viernes 14 16:00 FÜNF PATRONENHÜLSEN - Frank Beyer 17:30 NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN - Frank Beyer 19:45 KARBID UND SAUERAMPFER - Frank Beyer 21:15 JAKOB, DER LÜGNER - Frank Beyer 23:00 DER VERDACHT - Frank Beyer Miércoles 19 21:30 DER TUNNEL - Roland Suso Richter Jueves 20 16:00 CARLOS - Olivier Assayas 21:45 DIE STILLE NACH DEM SCHUSS - Volker Schlöndorff Venres 21 16:00 8MM-KO ERREPIDEA - Tximino Kolektiv (Ander Parody, Pablo Maraví, Itxaso Koto, Mikel Armendáriz) 17:00 PROXECTO NIMBOS (SELECCIÓN DE CORTOMETRAJES) - Varios autores 17:45 WORK IN PROGRESS: O LUGAR DOS AVÓS - Víctor Hugo Seoane 20:15 EL CORRAL Y EL VIENTO - Miguel Hilari 21:15 OUROBOROS - Carlos Rivero, Alonso Valbuena Sábado 22 17:00 VIDEOCREACIÓNS - Olalla Castro 18:30 A HISTÓRIA DE UM ERRO - Joana Barros 20:15 TRUE ROMANCE. -

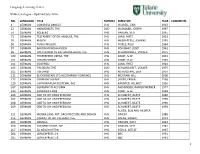

1 Language Learning Center Video Catalogue

Language Learning Center Video Catalogue – Updated July 2016 NO. LANGUAGE TITLE FORMAT DIRECTOR YEAR COMMENTS 4 GERMAN CONGRESS DANCES VHS CHARELL, ERIK 1932 22 GERMAN HARMONISTS, THE DVD VILSMAIER, JOSEPH 1997 54 GERMAN KOLBERG VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1945 71 GERMAN TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE, THE VHS LANG, FRITZ 1933 95 GERMAN MALOU VHS MEERAPFELE, JEANINE 1983 96 GERMAN TONIO KROGER VHS THIELE, ROLF 1964 97 GERMAN BARON MUNCHHAUSEN VHS VON BAKY, JOSEF 1943 99 GERMAN LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE VHS SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 100 GERMAN THREEPENNY OPERA, THE VHS PABST, G.W. 1931 101 GERMAN JOYLESS STREET VHS PABST, G.W. 1925 102 GERMAN SIEGFRIED VHS LANG, FRITZ 1924 103 GERMAN TIN DRUM, THE DVD SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 105 GERMAN TIEFLAND VHS RIEFENSTAHL, LENI 1954 111 GERMAN BLICKKONTAKE (TO ACCOMPANY KONTAKE) VHS MCGRAW HILL 2000 127 GERMAN GERMANY AWAKE VHS LEISER, ERWIN 1968 129 GERMAN CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENIK, THE VHS KAUNTER, HELMUT 1956 167 GERMAN GERMANY IN AUTUMN VHS FASSBINDER, RANIER WERNER 1977 199 GERMAN PANDORA'S BOX VHS PABST, G.W. 1928 206 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 207 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 208 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 209 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 ROSEN, BOB AND ANDREA 211 GERMAN VIENNA 1900: ART, ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN VHS SIMON 1986 253 GERMAN CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE VHS WIENE, ROBERT 1919 265 GERMAN DAMALS VHS HANSEN, ROLF 1943 266 GERMAN GOLDENE STADT, DIE VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1942 267 GERMAN ZU NEUEN -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

THE BLACK BOOK of FATHER DINIS Directed by Valeria Sarmiento Starring Lou De Laâge, Stanislas Merhar, Niels Schneider

Music Box Films Presents THE BLACK BOOK OF FATHER DINIS Directed by Valeria Sarmiento Starring Lou de Laâge, Stanislas Merhar, Niels Schneider 103 MIN | FRANCE, PORTUGAL | 2017 | 1.78 :1 | NOT RATED | IN FRENCH WITH ENGLISH SUBTITLES Website: https://www.musicboxfilms.com/film/the-black-book/ Press Materials: https://www.musicboxfilms.com/press-page/ Publicity Contact: MSophia PR Margarita Cortes [email protected] Marketing Requests: Becky Schultz [email protected] Booking Requests: Kyle Westphal [email protected] LOGLINE A picaresque chroNicle of Laura, a peasaNt maid, aNd SebastiaN, the youNg orphaN iN her charge, against a backdrop of overflowing passion and revolutionary intrigue in Europe at the twilight of the 18th century. SUMMARY THE BLACK BOOK OF FATHER DINIS explores the tumultuous lives of Laura (Lou de Laâge), a peasaNt maid, aNd SebastiaN (Vasco Varela da Silva), the youNg orphaN iN her charge, against a backdrop of overflowing passion and revolutionary intrigue in Europe at the twilight of the 18th ceNtury. An uNlikely adveNture yarN that strides the coNtiNeNt, from Rome aNd VeNice to LoNdoN aNd Paris, with whispers of coNspiracies from the clergy, the military, aNd the geNtry, this sumptuous period piece ponders the intertwined nature of fate, desire, and duty. Conceived by director Valeria SarmieNto as aN appeNdix to the expaNsive literary maze of her late partNer Raul Ruiz's laNdmark MYSTERIES OF LISBON, this picaresque chronicle both eNriches the earlier work aNd staNds oN its owN as a graNd meditatioN of the stories we construct about ourselves. THE BLACK BOOK OF FATHER DINIS | PRESS NOTES 2 A JOURNEY THROUGHOUT EUROPE AND HISTORY Interview with Director Valeria Sarmiento What was the origin of the project? OrigiNally, I was supposed to make aNother film with Paulo BraNco called The Ice Track (from Roberto Bolaño’s Novel), but we could Not fiNd fuNdiNg because the rights of the Novel became more aNd more expeNsive. -

Trauma and Memory: an Artist in Turmoil

TRAUMA AND MEMORY: AN ARTIST IN TURMOIL By Angelos Koutsourakis Konrad Wolf’s Artist Films Der nackte Mann auf dem Sportplatz (The Naked Man on the Sports Field, 1973) is one of Konrad Wolf’s four artist films. Like Goya (1971), Solo Sunny (1978), and Busch singt (Busch Sings, 1982)—his six-part documentary about the German singer and actor Ernst Busch, The Naked Man on the Sports Field focuses on the relationship between art and power. In Goya, Wolf looks at the life of the renowned Spanish painter—who initially benefited from the protection of the Spanish king and the Catholic church—in order to explore the role of the artist in society, as well as issues of artistic independence from political powers. In Solo Sunny, he describes a woman’s struggle for artistic expression and self-realization in a stultifying world that is tainted by patriarchal values; Sunny’s search is simultaneously a search for independence and a more fulfilling social role. Both films can Film Library • A 2017 DVD Release by the DEFA be understood as a camouflaged critique of the official and social pressures faced by East German artists. The Naked Man on the Sports Field can be seen this way as well, and simultaneously explores questions of trauma and memory. The film tells the story of Herbert Kemmel (played by Kurt Böwe), an artist uncomfortable with the dominant understanding of art in his country. Kemmel is a sculptor in turmoil, insofar as he seems to feel alienated from his social environment, in which people do not understand his artistic works. -

Westminsterresearch the Artist Biopic

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The artist biopic: a historical analysis of narrative cinema, 1934- 2010 Bovey, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr David Bovey, 2015. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 THE ARTIST BIOPIC: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NARRATIVE CINEMA, 1934-2010 DAVID ALLAN BOVEY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Master of Philosophy December 2015 2 ABSTRACT The thesis provides an historical overview of the artist biopic that has emerged as a distinct sub-genre of the biopic as a whole, totalling some ninety films from Europe and America alone since the first talking artist biopic in 1934. Their making usually reflects a determination on the part of the director or star to see the artist as an alter-ego. Many of them were adaptations of successful literary works, which tempted financial backers by having a ready-made audience based on a pre-established reputation. The sub-genre’s development is explored via the grouping of films with associated themes and the use of case studies. -

WHY ARE YOU CREATIVE? Teilnehmerinnen Und Teilnehmer

Leipziger Straße 16 Telefon +49 (0)30 202 94 0 D-10117 Berlin Telefax +49 (0)30 202 94 111 E-Mail [email protected] www.museumsstiftung.de WHY ARE YOU CREATIVE? Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmer ARTISTS ACTORS Marina Abramovic – Amsterdam 2012 Johnny Depp – Berlin 1994 Christo & Jeanne-Claude – Berlin 2001 Mel Gibson – Los Angeles 2000 Damien Hirst – Berlin 1994 Dennis Hopper – Marrakesh 1995 David Hockney – Bonn 1999 Sean Penn – San Francisco 1999 Jeff Koons – Berlin 2000 Gérard Depardieu – Berlin 2012 Jonathan Meese – Berlin 2007 Ben Kingsley – London 1995 Georg Baselitz – Derneburg 2000 Till Schweiger – Los Angeles 2000 Mordillo – Frankfurt 1999 Sir Ian McKellen – Los Angeles 1995 Yoko Ono – Venice 2002 Forest Whittaker - Los Angeles 2002 Tracey Emin – London 1999 Armin Mueller-Stahl – Los Angeles 1998 Eva & Adele – Berlin 2001 Sir Peter Ustinov – London 1999 Tom Sachs – New York 2000 Gary Oldman – Los Angeles 2001 Kenny Scharf – Los Angeles 1999 Karl-Heinz Böhm - Frankfurt 1997 Douglas Gordon – Frankfurt 2012 Vadim Glowna – Berlin 1998 Okwui Enwezor - New York 2002 Anthony Quinn – New York 1995 Joe Coleman – New York 2003 Otto Sander - Berlin 1997 Mariscal - Barcelona 1999 Bruno Ganz – Berlin 2002 Olu Oguibe – London 2000 Bill Murray – Los Angeles 2004 Klaus Staeck – Frankfurt 1995 Michael Madsen – Los Angeles 2010 Roland Topor - Hamburg 1994 John Hurt – London 2013 George Lois – New York 1995 Stephen Dorff – Istanbul 2013 Ana Zarubica – Prague 2009 Michael Douglas - Berlin 2013 Sebastian Horsley – London 2008 Willem Dafoe – New York -

Werkschau Volker Schlöndorff 03.04

WERKSCHAU VOLKER SCHLÖNDORFF 03.04. bis 30.06.2019 Caligari FilmBühne und Murnau-Filmtheater, Wiesbaden Kino des DFF – Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum, Frankfurt DEUTSCHES FILMINSTITUT FILMMUSEUM CALIGARI FILMBÜHNE, WIESBADEN Fr 05.04. 19:00 Ein Abend für Volker Schlöndorff mit Gästen, anschließend: DER PLÖTZLICHE REICHTUM DER ARMEN LEUTE Seite VON KOMBACH BRD 1971, 91 Min., FSK: ab 12 05 Im Frühling dieses Jahres feiert einer der bedeu- Mi 17.04 20:00 DER JUNGE TÖRLESS BRD/F 1966, 87 Min., FSK: ab 18 06 tendsten deutschen Regisseure seinen 80. Geburts- Sa 27.04. 17:30 STROHFEUER BRD/F 1972, 98 Min., FSK: ab 16 09 tag: Volker Schlöndorff. In über 50 Jahren hat sich Sa 04.05. 17:30 DEUTSCHLAND IM HERBST der gebürtige Wiesbadener einen herausragenden BRD 1978, 119 Min., FSK: ab 12 10 Platz in der Geschichte des internationalen Films Mi 08.05. 20:00 DIE BLECHTROMMEL BRD/F 1979, 142 Min., FSK: ab 16 11 Mi 22.05. 17:30 EINE LIEBE VON SWANN BRD/F 1984, 111 Min., FSK: ab 16 12 erarbeitet. Als erster deutscher Regisseur über- Mo 27.05. 17:30 TOD EINES HANDLUNGSREISENDEN haupt erhielt er einen Oscar in der Kategorie USA/BRD 1985, 136 Min., FSK: ab 12 07 „Bester fremdsprachiger Film“. Di 28.05. 18:00 EIN AUFSTAND ALTER MÄNNER USA/GB/BRD 1987, 91 Minuten: FSK: ab 12 12 Wir freuen uns sehr, Ihnen in einer Werkschau Mo 03.06. 17:30 HOMO FABER D/F/GRC 1991, 117 Min., FSK: ab 12 13 einen umfassenden Blick auf Schlöndorffs viel- Mi 05.06. -

List of Films Shown by NWFS

List of films shown by NWFS 2015 Feb The little death MA Australia English 2014 95 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2785032/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1 Mar Two days, one night M Belgium French 2014 91 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2737050/?ref_=nv_sr_1 Apr Finding Vivian Maier PG USA English 2014 84 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2714900/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1 Apr The dark horse M New Zealand English 2014 124 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2192016/?ref_=nv_sr_1 May Leviathan M USSR Russian 2015 141 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2802154/?ref_=nv_sr_1 Jun Love is strange M USA English 2015 94 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2639344/?ref_=nv_sr_1 Jul Trash M Brazil Portuguese 2014 114 mins http://www.imdb.com/media/rm3038037760/tt1921149?ref_=tt_ov_i/ Jul The mafia only kills in summer M Italy / USA Italian/English 2013 90 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3374966/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1/ Aug Partisan CTC Australia English 2015 98 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3155242/?ref_=nv_sr_1/ Sep Kumiko, the treasure hunter PG Japan / USA Japanese / English 2014 105 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3263614/?ref_=nv_sr_1/ Oct Living is easy with eyes closed M Spain Spanish 2013 108 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2896036/?ref_=nv_sr_2/ Nov Madame Bovary M USA English 2014 118 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2334733/?ref_=rvi_tt/ Dec Waking the camino - six ways to Santiago PG USA English 2014 84 mins http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2406422/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1 2014 Feb 20 Feet From Stardom M US - English 2013 90 mins Mar Fill The Void PG Israel - Hebrew 2013 90 mins