Pesach Sheni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thetorah -Com

6t9t2U2U I ne Paraoox oI Pesacn :inenr - | ne I oran.com TheTorah -com The Paradox of Pesach Sheni As a historical commemoration, Passover is tied to a specific date. Nevertheless, the Torah gives a make-up date for bringing the offering a month later. Gerim, non- Israelites living among Israelites as equals, are also allowed to bring this offering, even though it wasn)t their ancestors who were freed. How do we make sense of these anomalies? Prof. Steven Fraade u* ntrs .!i.aitrir! i'irir;ri{,r I t i I I 5* \} - A Fixed Lunar-Calendrical Commemoration: A fter explaining to Moses how the Israelites should perform the Passover I I ritual in order to avoid being killed during the plague of the firstborn, YHWH endswith: El? nll triri nin] T:rr ntDur ExodD:14 This day shallbe to you one of ;r:;r-! rf inx onirrlr firpr5 remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a hltns'//unrnrr thelnrah enm/artinlc/the-naradav-nf-nceanh-ehpni 1 111 6t9t2U2t) I he Paradox ot Pesach shent - | ne loran.com .r;lilT tr?i9 ni?l;| tr)!I-r1' festival to YHWH throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. Moses then passes the message along to the elders of Israel, expanding on this point: 'D:r' niDu' Exod'12:2t+ l?:Tn n$ trR"lDt?l You shall observe this as an .o?ip ru Tt;}'r! il4);'rrn institution for all time, for you and for ;'1):r' f':lqt? tli tNff '? i"l';r'l your descendants. -

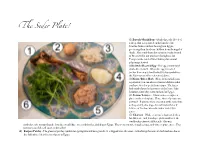

The Seder Plate

Te Seder Plate! (1) Zaroah/Shank Bone - Symbolizes the blood of a sheep that was painted on the lintels of the Israelite homes on their last night in Egypt, protecting their firstborn children from the angel of death. Also symbolizes the sacrifice for the festival of Passover that our ancestors brought to the Temple in the land of Israel during this annual pilgrimage festival. (2)Beitzah/Roasted Egg - The egg is round and symbolizes rebirth. When the egg is roasted (rather than simply hard boiled) it also symbolizes the Passover sacrifice referenced above. (3)Maror/Bitter Herb - Here, horseradish paste is pictured; you can also use horseradish root that you have sliced or peeled into strips. The bitter herb symbolizes the bitterness of the lives of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. (4) Potato/Lettuce - Often lettuce occupies a place on the seder plate. Here, slices of potato are pictured. If potato, these are eaten at the same time as the parsley, also dipped in salt water (6) or if lettuce, at the time when the bitter herb (3) is eaten. (5) Charoset - While everyone’s charoset looks a bit different - and Jewish people from all over the world make charoset differently - this mix symbolizes the mortar that the Israelites would have used with bricks, building in Egypt. This is often a mix of apples, nuts, and wine or grape juice. This sweetness is a beloved taste of the seder! (6) Karpas/Parsley - The green of parsley symbolizes springtime and new growth. It is dipped into salt water, symbolizing the tears of the Israelites due to the difficulty of their lives in slavery in Egypt.. -

AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH An-Exquisite-Medieval-Haggadah

ON VIEW FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 100 YEARS: AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/arts-culture/2019/04/on-view-for-the-first-time-in-100-years- an-exquisite-medieval-haggadah/ A few months ago, I was approached with a request to become involved in a then- secret mission: to examine one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands. April 23, 2019 | Marc Michael Epstein A few months ago, a highly regarded expert in medieval manuscripts approached me with a request to become involved in a then-secret mission. Sandra Hindman is a scholar who—through her Les Enluminures galleries in Paris, Chicago, and New York —aids and guides libraries, institutions, and private individuals in acquiring some of the best and last-surviving products of medieval illuminators and their workshops. To this end, she has A page from the Lombard Haggadah. Les issued a series of meticulously Enluminures. researched catalogues describing and interpreting such manuscripts. Although it’s unusual for her to devote one of these catalogues to a single manuscript, this one, Hindman felt, was worthy of the attention. Would I have a look? I would indeed. A few days later, my assistant Gabriel Isaacs and I set out for Manhattan’s Upper East Side expecting to be shown a charter, a loan contract, a Bible with some Hebrew glosses or annotations, or perhaps a Book of Hours depicting Jews in particularly vicious caricature. Little could we have guessed what awaited us: one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands, and a supremely fascinating one. -

Passover and the Last Supper, Tyndale Bulletin 53.2 (2002)

Tyndale Bulletin 53.2 (2002) 203-221. PASSOVER AND LAST SUPPER Robin Routledge Summary The Synoptic Gospels present the Last Supper as a Passover meal. Whether this coincided with the actual Passover or, as some suggest, was held a day early, it was viewed by the participants as a Passover meal, and the words and actions of Jesus, including the institution of the Lord’s Supper, would have been understood within that context. In order to better appreciate the significance of what happened at the Last Supper, this article looks at the form that the Passover celebration is likely to have taken at the time of Jesus, and notes links with the meal Jesus shared with his disciples. I. Introduction The Old Testament gives details of festivals appointed by God which are linked with historical events and which serve as a continuing reminder of God’s saving power. These celebrations are rich in theological content, and also contain symbolism that points ultimately to Jesus, in whom the deeper significance of the festivals is fulfilled. In addition to their theological and symbolic significance, because the observance of these festivals was part of Jewish worship in the first century CE, knowing about them helps us to understand more about the world in which Jesus and the early Church lived and taught. For most Gentile believers, though, that is as far as the interest goes. Jesus observed the traditional Jewish holidays,1 but that was because he was born a Jew; in general Gentile believers were not expected to observe what would have been, to them, part of a foreign culture.2 The link between Jesus and the Passover presented in the New Testament, however, gives this festival a special importance for 1 E.g. -

Shabbos Chol Hamoed Pesach When Eating Is a Mitzvah

ב''ה SERMON RESOURCE FOR SHLUCHIM שבת חול - המועד פסח /SHABBOS CHOL HAMOED PESACH WHEN EATING IS A MITZVAH DISTRIBUTION DATE: י"א ניסן תשס"ט / TUESDAY APRIL 5, 2009 PARSHA: שבת חול - המועד פסח /SHABBOS CHOL HAMOED PESACH SERMON TITLE: WHEN EATING IS A MITZVAH Sponsored by Shimon Aron & Devorah Leah Rosenfeld & Family A PROJECT OF THE SHLUCHIM OFFICE In loving memory of 1 ר' מנחם זאב בן פנחס ז''ל Emil W. Herman Z י"א ניסן תשס"ט • DISTRIBUTION DATE: TUESDAY APRIL 5, 2009 The author is solely responsible for the contents of this document. who loved and supported Torah learning. ב''ה SERMON RESOURCE FOR SHLUCHIM שבת חול - המועד פסח /SHABBOS CHOL HAMOED PESACH WHEN EATING IS A MITZVAH שבת חול - המועד פסח /SHABBOS CHOL HAMOED PESACH WHEN EATING IS A MITZVAH A stranger stranded in a Jewish home who tries to learn about Jewish life will come to the conclusion that out of the 613 mitzvos, at least 600 of them have to do with food. On Shabbos, for example, the Jews are constantly busy with food, whether gefilte fish, chicken soup or cholent. Any Jewish holiday, when you think about it, has its own special food, whether hamantashen on Purim, latkes on Chanukah, kreplach before Yom Kippur or kneidlach on Passover—everything revolves around food. But when you really look at Jewish holidays you realize that every holiday has a mitzvah that makes it unique: Rosh Hashanah has the shofar, Chanukah has the menorah, Sukkos has the sukkah, and Purim has the megillah. Each one has its own Jewish ritual. -

Bob Haggadah - Emphasizing the Symbols Contributed by Josh Bob Source: Bob Family Haggadah

Bob Haggadah - Emphasizing the Symbols Contributed by Josh Bob Source: Bob Family Haggadah Emphasizing the Symbols of Passover [Lift up the Seder plate and point out each item. Explain the purpose behind each item:] Maror (bitter herbs) Bitter Herbs (usually horseradish) symbolize the bitterness of Egyptian slavery. Maror is used in the Seder because of the commandment to eat the paschal lamb "with unleavened bread and bitter herbs." Karpas (vegetable) Vegetable (usually parsley) is dipped into salt water during the Seder. The salt water represents the tears shed during Egyptian slavery. The dipping of a vegetable as an appetizer is said to date back to biblical times. Charoset (apple, nut, spice and wine mixture) Apple, nuts, and spices ground together and mixed with wine are symbolic of the mortar used by Hebrew slaves to build Egyptian structures. The Charoset is sweet because sweetness is symbolic of God's kindness, which was able to make even slavery more bearable. According to legend, the use of apples in charoset stems from Pharaoh's decree that all male Hebrew children were to be killed at birth. Mothers would go out to the orchards to give birth, and thus save their babies (at least temporarily) from the Egyptian soldiers. Zeroa (shankbone) The Shankbone is symbolic of the Paschal lamb offered as the Passover sacrifice in biblical times. In some communities, it is common to use a chicken neck in place of the shankbone. Vegetarian households often use beets for the shankbone on the seder plate. The red beets symbolize the blood of the Paschal lamb, which was used to mark the lintel and doorposts of the houses during the first Passover (Exodus 12:22). -

The Techniques of the Sacrifice

Andm Univcrdy Seminary Stndics, Vol. 44, No. 1,13-49. Copyright 43 2006 Andrews University Press. THE TECHNIQUES OF THE SACRIFICE OF ANIMALS IN ANCIENT ISRAEL AND ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA: NEW INSIGHTS THROUGH COMPARISON, PART 1' JOANNSCURLOCK ELMHURSTCOLLEGE Elmhurst, Illinois There is an understandable desire among followers of religions that are monotheistic and that claim descent from ancient Israelite religion to see that religion as unique and completely at odds with its surroundrng polytheistic competitors. Most would not deny that there are at least a few elements of Israelite religion that are paralleled in neighboring cultures, as, e.g., the Hittites: 'I would like to thank the following persons who read and commented on earlier drafts of this article: R. Bed, M. Hilgert, S. Holloway, R. Jas, B. Levine and M. Murrin. Abbreviations follow those given in W. von Soden, AWches Han&rterbuch, 3 301s. (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1965-1981); and M. Jursa and M. Weszeli, "Register Assyriologie," AfO 40-41 (1993/94): 343-369, with the exception of the following: (a) series: D. 0.Edzard, Gnda and His Dynarg, Royal Inscriptions of Mesopommia: Early Periods (RIME) 311 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997); S. Parpola and K. Watanabe, Neo-Assyrin Treatzes and Lq&y Oaths, State Archives of Assyria (SAA) 2 (Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 1988); A. Livingstone, Court Poety and Literq Misceubnea, SAA 3 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1989); I. Starr,QnerieJ to the Sungod, SAA 4 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1990); T. Kwasrnan and S. Parpola, Lga/ Trama~~lom$the RoyaiCoz& ofNineveh, Part 1, SAA 6 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1991); F. -

The Haggadah of Passover

The Haggadah of Passover Copyright Jack Doppelt 2020 Haggadah simply means a “telling” or a “narrative.” This year’s Haggadah is a tale being told in the midst of a plague, not unlike the plagues of old. The guiding principle of a Haggadah is that for “each person in each generation to regard himself as having been personally freed from Egypt,” that person must share in the pain, the joy, the unrelenting hope and the universality of the Jewish and human experience. ---------------------------------------------- The Seder begins with the lighting of candles and the Kiddush over a cup of wine as is customary on the eve of every Shabbas and holy day. Seder means “order,” indicating that the service and the meal have been prearranged with a definite purpose and with rich remembrances in mind. 1 BA-RUCH A-TA A-DO-NAI E-LO-HAY-NU ME-LECH HA-O-LAM A-SHER KI- DE-SHA-NU BE-MITZ-VO-TAV VE-TZI-VA-NU LE-HAD-LIK NER SHEL (SHABBAT V') YOM TOV. BA-RUCH A-TA A-DO-NAI E-LO-HAY-NU ME-LECH HA-O-LAM SHE-HE- CHE-YA-NU VE-KI-YE-MA-NU VE-HIG-I-YA-NU LAZ-MAN HA-ZEH. Raise a glass: Baruch Atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech ha-olam, borei p'ri ha-gafen. (Drink from the first cup of wine) There is more, as you can see, to the Seder than candles and wine, or even four cups of wine. There is a Seder plate. Most seder plates have six dishes for the six symbols of the Passover seder. -

Happy Happy Passover ! Assover

PASSOVER DIRECTORY ~ 5781 - 2021 HAPPY PASSOVER ! From the Seattle Va’ad Passover Directory 2021/5781 The Va'ad hopes this guide will help the consumer get the most out of the Passover holiday. All information is, to the best of our knowledge, correct as of the time of posting 03/01/2021. Please monitor the Va'ad website for updates as they become available. Please direct any questions or comments to: The Va'ad HaRabanim of Greater Seattle, 5305 52nd Avenue South, Seattle, WA 98118. Phone: 206-760-0805 Fax: 206-725-0347 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.seattlevaad.org We welcome your comments and wish you and your family a Happy and Kosher Passover, Chag Sameach, Moadim LeSimha, Gut Yom Tov. This guide encompasses the traditions of Seattle’s Ashkenazi and Sephardi communities. As always, questions about specific individual or community practices and traditions should be addressed to your Synagogue Rabbi. For Passover questions, please email Rabbi Kletenik at: [email protected] PLEASE CHECK FOR UPDATES AT: http://seattlevaad.org/passover/ PASSOVER DIRECTORY 5781 – 2021 MARCH 03, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………….(2) II. PESACH LAWS AND CUSTOMS …………………………………………………...(2) III. A. CHAMETZ …………………………………………………………..………………(3) BUYING FOOD BEFORE AND AFTER PESACH ………….………………..(4) B. KITNIOT ………………………………………………………………….………….(5) C. GEBRUKTS …………………………………………………………………………(6) IV. MATZA …………………………………………………………………………………..(6) V. MEDICINES, COSMETICS, AND PET FOOD……………………………………….(7) A. MEDICINES………………………………………………………………………….(7) B. TOILETRIES AND COSMETICS………………………………………………….(7) C. PET FOOD…………………………………………………………………………...(8) VI. FOOD………………………………………………… ………………………………….(9) A. SOME COMMON FOOD ISSUES FOR PESACH………………………………(9) B. EGGS…………………………………………………………………………………(9) C. MILK AND DAIRY PRODUCTS……………………………………………..........(9) D. GENERAL POINTERS ON PASSOVER SUPERVISION………………………(9) VII. -

Archetype and Adaptation: Passover Haggadot from the Stephen P

Archetype and Adaptation: Passover Haggadot from the Stephen P. Durchslag Collection The week-long, springtime Jewish holiday of Pesach, or Passover, is beloved for its symbolic meaning and joyous customs. Passover marks the freeing of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, a narrative with universal appeal as a paradigm for collective and, according to some traditions, personal liberation. The Haggadah (plural: Haggadot), or “telling,” is the collection of prayers, legends, and stories recited on the eve of Passover. The basic text derives from the biblical instruction to retell the story of the Exodus each year during Passover in conjunction with a ritual meal called the Seder, or “order” (Exodus 13:8). Over the centuries songs and illustrations have been added to engage children, to whom the story was to be told, and some passages are given added prominence when they resonate with contemporary concerns. Illustrations in medieval manuscripts depict scenes from Exodus, the life of Moses, and Jewish Patriarchs. Many of these scenes continue to appear in early printed Haggadot, but the emphasis shifts to passages drawn directly from the text. The Haggadah has shown remarkable stability and flexibility: thousands of editions in all languages testify to its central role in Jewish life and its ability to incorporate new themes and respond to changing conditions. This exhibition is drawn entirely from the private collection of Stephen P. Durchslag, the largest known collection of Haggadot in private hands. “Archetype and Adaptation” explores the enduring influence of early printed Haggadot as well as the ability of modern versions to reflect political and social developments such as the Holocaust, Zionism, gay rights, and feminism. -

The Seder Meal: a Messianic Passover Haggadah

The Seder Meal: A Messianic Passover Haggadah This is an abbreviated celebration of the Seder Meal of the Jewish feast of Passover, adapted to explain the messianic significance of this Jewish feast. It would ideally be celebrated in a family setting, on or before Holy Thursday, as a way to foster appreciation of, and anticipation for the liturgical celebration of the Mass of the Lord’s Supper. Items normally used: Candle(s) Wine (or juice for children) Matzoh or unleavened flat bread (spread a flour and water paste on a cookie sheet with a little salt. Prick with a fork and bake) Parsley (or another green vegetable) Salt water A white cloth or napkin Maror (bitter herbs): usually a mixture of horseradish and romaine lettuce Haroset, made from apples, cinnamon, honey, nuts, and wine More wine Roast lamb (or any meat) The rest of the meal You may want to read from the 12th chapter of the Book of Exodus in the Bible. Introduction FATHER (or oldest man): The Passover/Easter stories have been told over and over for thousands of years, stories about miraculous change from misery to peace, slavery to freedom, sin to grace. One of the last things Jesus did with his disciples was to celebrate Passover and retell the story to them. It's no coincidence Jesus chose the Passover meal for what the Church now celebrates as the Mass and Eucharist. God gave us the Passover celebration and He used the same celebration to teach us even more about His love. God cared for His people, our ancestors, long ago and He cares for His children today. -

1 Second Chances – Parashat B'haalotcha Besides Being the Man for Whom the Nobel Prize Is Named, Alfred Nobel Was Also the I

Second Chances – Parashat B’haalotcha Besides being the man for whom the Nobel Prize is named, Alfred Nobel was also the inventor of dynamite. What would inspire a manufacturer of explosives to dedicate his fortune to creating the premiere award bestowed upon those who have benefited humanity? Strangely enough, it was a printing error. When Nobel’s brother passed away, a newspaper ran a lengthy article about Alfred Nobel, mistakenly thinking that it was he who had died. Nobel had the rare opportunity to do what very few people can – to read his obituary while still alive – and it absolutely terrified him. The paper described Nobel as a person who had made it possible for more people to be killed more quickly than anyone else who had ever lived. In that moment, Nobel realized that this was not the way he wished to be remembered and it inspired him to change his life. Today, few people associate the name Nobel with dynamite but rather with a dedication to advancing society. Alfred Nobel had the privilege of being given a second chance, and he was wise enough to take advantage of it. Where would we be today were it but not for second chances? From the silly mistakes of our youth to the missteps and miscalculations of adult life, the errors in judgment that got us into trouble, the times when what we thought we really wanted turned out not to be quite right, the circumstances beyond our control that landed us in a tough spot, and the times we just plain acted badly - how grateful we are to have had the opportunity to bounce back from difficult times.