Archetype and Adaptation: Passover Haggadot from the Stephen P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KIVUNIM Comes to Morocco 2018 Final

KIVUNIM Comes to Morocco March 15-28, 2018 (arriving from Spain and Portugal) PT 1 Charles Landelle-“Juive de Tanger” Unlike our astronauts who travel to "outer space," going to Morocco is a journey into "inner space." For Morocco reveals under every tree and shrub a spiritual reality that is unlike anything we have experienced before, particularly as Jewish travelers. We enter an Islamic world that we have been conditioned to expect as hostile. Instead we find a warmth and welcome that both captivates and inspires. We immediately feel at home and respected as we enter a unique multi-cultural society whose own 2011 constitution states: "Its unity...is built on the convergence of its Arab-Islamic, Amazigh and Saharan-Hassani components, is nurtured and enriched by African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean constituents." A journey with KIVUNIM through Morocco is to glimpse the possibilities of the future, of a different future. At our alumni conference in December, 2015, King Mohammed VI of Morocco honored us with the following historic and challenge-containing words: “…these (KIVUNIM) students, who are members of the American Jewish community, will be different people in their community tomorrow. Not just different, but also valuable, because they have made the effort to see the world in a different light, to better understand our intertwined and unified traditions, paving the way for a different future, for a new, shared destiny full of the promises of history, which, as they have realized in Morocco, is far from being relegated to the past.” The following words of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel remind us of the purpose of our travels this year. -

THE TEN PLAGUES of EGYPT: the Unmatched Power of Yahweh Overwhelms All Egyptian Gods

THE TEN PLAGUES OF EGYPT: The Unmatched Power of Yahweh Overwhelms All Egyptian Gods According to the Book of Exodus, the Ten Plagues were inflicted upon Egypt so as to entice their leader, Pharaoh, to release the Israelites from the bondages of slavery. Although disobedient to Him, the Israelites were God's chosen people. They had been in captivity under Egyptian rule for 430 years and He was answering their pleas to be freed. As indicated in Exodus, Pharaoh was resistant in releasing the Israelites from under his oppressive rule. God hardened Pharaoh's heart so he would be strong enough to persist in his unwillingness to release the people. This would allow God to manifest His unmatched power and cause it to be declared among the nations, so that other people would discuss it for generations afterward (Joshua 2:9-11, 9:9). After the tenth plague, Pharaoh relented and commanded the Israelites to leave, even asking for a blessing (Exodus 12:32) as they departed. Although Pharaoh’s hardened heart later caused the Egyptian army to pursue the Israelites to the Red Sea, his attempts to return them into slavery failed. Reprints are available by exploring the link at the bottom of this page. # PLAGUE SCRIPTURE 1 The Plague of Blood Exodus 7:14-24 2 The Plague of Frogs Exodus 7:25- 8:15 3 The Plague of Gnats Exodus 8:16-19 4 The Plague of Flies Exodus 8:20-32 5 The Plague on Livestock Exodus 9:1-7 6 The Plague of Boils Exodus 9:8-12 7 The Plague of Hail Exodus 9:13-35 8 The Plague of Locusts Exodus 10:1-20 9 The Plague of Darkness Exodus 10:21-29 10 The Plague on the Firstborn Exodus 11:1-12:30 --- The Exodus Begins Exodus 12:31-42 http://downriverdisciples.com/ten-plagues-of-egypt . -

Thetorah -Com

6t9t2U2U I ne Paraoox oI Pesacn :inenr - | ne I oran.com TheTorah -com The Paradox of Pesach Sheni As a historical commemoration, Passover is tied to a specific date. Nevertheless, the Torah gives a make-up date for bringing the offering a month later. Gerim, non- Israelites living among Israelites as equals, are also allowed to bring this offering, even though it wasn)t their ancestors who were freed. How do we make sense of these anomalies? Prof. Steven Fraade u* ntrs .!i.aitrir! i'irir;ri{,r I t i I I 5* \} - A Fixed Lunar-Calendrical Commemoration: A fter explaining to Moses how the Israelites should perform the Passover I I ritual in order to avoid being killed during the plague of the firstborn, YHWH endswith: El? nll triri nin] T:rr ntDur ExodD:14 This day shallbe to you one of ;r:;r-! rf inx onirrlr firpr5 remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a hltns'//unrnrr thelnrah enm/artinlc/the-naradav-nf-nceanh-ehpni 1 111 6t9t2U2t) I he Paradox ot Pesach shent - | ne loran.com .r;lilT tr?i9 ni?l;| tr)!I-r1' festival to YHWH throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. Moses then passes the message along to the elders of Israel, expanding on this point: 'D:r' niDu' Exod'12:2t+ l?:Tn n$ trR"lDt?l You shall observe this as an .o?ip ru Tt;}'r! il4);'rrn institution for all time, for you and for ;'1):r' f':lqt? tli tNff '? i"l';r'l your descendants. -

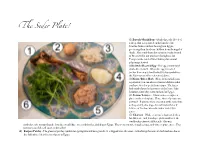

The Seder Plate

Te Seder Plate! (1) Zaroah/Shank Bone - Symbolizes the blood of a sheep that was painted on the lintels of the Israelite homes on their last night in Egypt, protecting their firstborn children from the angel of death. Also symbolizes the sacrifice for the festival of Passover that our ancestors brought to the Temple in the land of Israel during this annual pilgrimage festival. (2)Beitzah/Roasted Egg - The egg is round and symbolizes rebirth. When the egg is roasted (rather than simply hard boiled) it also symbolizes the Passover sacrifice referenced above. (3)Maror/Bitter Herb - Here, horseradish paste is pictured; you can also use horseradish root that you have sliced or peeled into strips. The bitter herb symbolizes the bitterness of the lives of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. (4) Potato/Lettuce - Often lettuce occupies a place on the seder plate. Here, slices of potato are pictured. If potato, these are eaten at the same time as the parsley, also dipped in salt water (6) or if lettuce, at the time when the bitter herb (3) is eaten. (5) Charoset - While everyone’s charoset looks a bit different - and Jewish people from all over the world make charoset differently - this mix symbolizes the mortar that the Israelites would have used with bricks, building in Egypt. This is often a mix of apples, nuts, and wine or grape juice. This sweetness is a beloved taste of the seder! (6) Karpas/Parsley - The green of parsley symbolizes springtime and new growth. It is dipped into salt water, symbolizing the tears of the Israelites due to the difficulty of their lives in slavery in Egypt.. -

SEDER Activities 2014

SEDER Activities 2014 Assignments to Prepare in advance: a.What the seder means to me in 6 words. Deposit in basket and pull out. Someone reads it and others guess to who wrote it. b. Write up two questions each about Pesach ritual, about Exodus and about Judaism – one simple fact question and one one-ended thought question. Deposit in basket and ask child to pick out four. c. This is your journey: Freedom from and freedom to: From what this year have you freed yourself and toward what new goals have you progressed. d. Dayenu. What have you experiences where yopu were so grateful you said: Dayenu. This is so satisfying that it has made my life worthwhile and me overjoyed. f. Shifra and Puah Award. Pick story of resistance to tyranny like midwives. g. Bring prop to tell one episode of Exodus (like backback, boots, basket). Then arrange all props in order of episodes from Biblical tale and and ask each person to retell their part in order. h. Nahshon Award. When did I stand up or see someone stand up to show courage against conformity or take first step in difficult process. i. Miracle. When did I experience that I felt was miraculous in colloquial usage (not necessarily supernatural) j.Favorite Peach memory or most bizarre seder. k. Choose quote about freedom and slavery that you agree with. Read outloud. Why did you choose it? l. What part of haggadah gives a message you think relevant to the President or prime Minister for his next term? m. -

Parashat Bo the Women Were There Nonetheless …

WOMEN'S LEAGUE SHABBAT 2016 Dvar Torah 2 Parashat Bo The Women Were There Nonetheless … Shabbat Shalom. In reading Parashat Bo this morning, I am intrigued by the absence of women and their role in the actual preparations to depart Egypt. This is particularly striking because women – Miriam, Moses’ mother Yocheved, the midwives Shifra and Puah, and Pharaoh’s daughter – are so dominant in the earlier part of the exodus story. In fact, the opening parashah of Exodus is replete with industrious, courageous women. Why no mention of them here? And how do we reconcile this difference? One of the ways in which moderns might interpret this is to focus on the context in which God commands Moses and the congregation of Hebrews – that is men – to perform certain tasks as they begin their journey out of Egypt. With great specificity God, through Moses, instructs the male heads of household how to prepare and eat the paschal sacrifice, place its blood on the doorpost, and remove all leaven from their homes. They are told how to ready themselves for a hasty departure. Why such detailed instruction? It is plausible that, like slaves before and after, the Hebrews had scant opportunity to cultivate imagination, creativity and independent thought during their enslavement. The opposite in fact is true, for any autonomous thought or deed is suppressed because the slave mentality is one of absolute submission to the will of his master. So this might account for why the Hebrew slaves required such specific instruction. The implication is that among the downtrodden, the impulse for freedom needs some prodding. -

How to Run a Passover Seder

How to Run a Passover Seder Rabbi Josh Berkenwald – Congregation Sinai We Will Cover: ´ Materials Needed ´ Haggadah ´ Setting up the Seder Plate ´ What do I have to do for my Seder to be “kosher?” ´ Music at the Seder ´ Where can I find more resources? Materials Needed – For the Table ü A Table and Tablecloth ü Seder Plate if you don’t have one, make your own. All you need is a plate. ü Chairs – 1 per guest ü Pillows / Cushions – 1 per guest ü Candles – 2 ü Kiddush Cup / Wine Glass – 1 per guest Don’t forget Elijah ü Plate / Basket for Matzah ü Matzah Cover – 3 Compartments ü Afikomen Bag ü Decorations Flowers, Original Art, Costumes, Wall Hangings, etc., Be Creative Materials Needed - Food ü Matzah ü Wine / Grape Juice ü Karpas – Leafy Green Vegetable Parsely, Celery, Potato ü Salt Water ü Maror – Bitter Herb Horseradish, Romaine Lettuce, Endive ü Charoset Here is a link to four different recipes ü Main Course – Up to you Gefilte Fish, Hard Boiled Eggs, Matzah Ball Soup Haggadah If you need them, order quickly – time is running out Lots of Options A Different Night; A Night to Remember https://www.haggadahsrus.com Make Your Own – Print at Home https://www.haggadot.com Sefaria All English - Jewish Federations of North America For Kids – Punktorah Setting Up the Seder Plate Setting Up the Matzah Plate 3 Sections Conducting the Seder 15 Steps of the Seder Kadesh Maror Urchatz Korech Karpas Shulchan Orech Yachatz Tzafun Magid Barech Rachtza Hallel Motzi Nirtza Matza Conducting the Seder 15 Steps of the Seder *Kadesh Recite the Kiddush *Urchatz Wash hands without a blessing *Karpas Eat parsley or potato dipped in salt water *Yachatz Break the middle Matza. -

Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close Rose Noël Wax Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 Part of the Food Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Wax, Rose Noël, "Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 176. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/176 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Rose Noël Wax Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 Acknowledgements Thank you to my parents for teaching me to be strong in my convictions. Thank you to all of the grandparents and great-grandparents I never knew for forging new identities in a country entirely foreign to them. -

Literacy in Medieval Jewish Culture1

Portrayals of Women with Books: Female (Il)literacy in Medieval Jewish Culture1 Katrin Kogman-Appel Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva The thirteenth century saw a new type of Hebrew book, the Passover haggadah (pl. haggadot). Bound together with the general prayer book in the earlier Middle Ages, the haggadah emerged as a separate, independent volume around that time.2 Once the haggadah was born as an individual book, a considerable number of illustrated specimens were created, of which several have come down to us. Dated to the period from approximately 1280 to 1500, these books were produced in various regions of the Iberian peninsula and southern France (Sepharad), the German lands (Ashkenaz), France, and northern Italy. Almost none of these manuscripts contain a colophon, and in most cases it is not known who commissioned them. No illustrated haggadah from the Islamic realm exists, since there the decoration of books normally followed the norms of Islamic culture, where sacred books received only ornamental embellishments. The haggadah is usually a small, thin, handy volume and contains the liturgical text to be recited during the seder, the privately held family ceremony taking place at the eve of Passover. The central theme of the holiday is the retelling of the story of Israel’s departure from Egypt; the precept is to teach it to one’s offspring.3 The haggadah contains the text to fulfill this precept. Hence this is not simply a collection of prayers to accompany a ritual meal; rather, using the 1 book and reading its entire text is the essence of the Passover holiday. -

Shabbat-B'shabbato – Parshat Metzora (Hagadol) No 1620: 8 Nissan 5776 (16 April 2016)

Shabbat-B'Shabbato – Parshat Metzora (Hagadol) No 1620: 8 Nissan 5776 (16 April 2016) AS SHABBAT APPROACHES Redemption, Prayer, and Torah Study - by Esti Rosenberg, Head of the Midrasha for Women, Migdal Oz In the introduction to his book "The Time of our Freedom" Rabbi Soloveitchik describes the mystic charm of the Seder night: "As a child I would stand and I was enthralled... I was hypnotized by this night... bright with the light of the moon, enveloped in beauty and glory... I was excited and filled with inspiration... Silence, quiet, peace, and a feeling of calm surrounded me. I became used to surrender to a flow of abundant joy and excitement." The Seder night incorporates within it an abstract of our entire religious world, and every Jewish family has the privilege of passing on the tradition of the generations from father to son and from mother to daughter. There are three main elements in the Seder night: The first element is the "story of the Exodus." The historical record is passed down from one generation to the next. Every generation tells the next one in line about the experience of redemption, about the matzot and the packages on the backs of the people, about leaving in the middle of the night, and about the emotional experience of moving from slavery to freedom. It is a first-person account, a true record of what happened to my own ancestors. The emphasis in the story is on personal experience, on faith, and on how the Holy One, Blessed be He, chose us as His nation. -

AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH An-Exquisite-Medieval-Haggadah

ON VIEW FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 100 YEARS: AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/arts-culture/2019/04/on-view-for-the-first-time-in-100-years- an-exquisite-medieval-haggadah/ A few months ago, I was approached with a request to become involved in a then- secret mission: to examine one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands. April 23, 2019 | Marc Michael Epstein A few months ago, a highly regarded expert in medieval manuscripts approached me with a request to become involved in a then-secret mission. Sandra Hindman is a scholar who—through her Les Enluminures galleries in Paris, Chicago, and New York —aids and guides libraries, institutions, and private individuals in acquiring some of the best and last-surviving products of medieval illuminators and their workshops. To this end, she has A page from the Lombard Haggadah. Les issued a series of meticulously Enluminures. researched catalogues describing and interpreting such manuscripts. Although it’s unusual for her to devote one of these catalogues to a single manuscript, this one, Hindman felt, was worthy of the attention. Would I have a look? I would indeed. A few days later, my assistant Gabriel Isaacs and I set out for Manhattan’s Upper East Side expecting to be shown a charter, a loan contract, a Bible with some Hebrew glosses or annotations, or perhaps a Book of Hours depicting Jews in particularly vicious caricature. Little could we have guessed what awaited us: one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands, and a supremely fascinating one. -

Haggadah SUPPLEMENT

Haggadah SUPPLEMENT Historical Legal Textual Seder Ritualistic Cultural Artistic [email protected] • [email protected] Seder 1) Joseph Tabory, PhD, JPS Haggadah 2 cups of wine before the meal ; 2 cups of wine after the meal (with texts read over each pair); Hallel on 2nd cup, immediately before meal; more Hallel on 4th cup, immediately after meal; Ha Lachma Anya – wish for Jerusalem in Aramaic - opens the seder; L’Shana HaBa’ah BiYerushalyaim – wish for Jerusalem in Hebrew - closes it; Aramaic passage (Ha Lachma Anya) opens the evening; Aramaic passage (Had Gadya) closes the evening; 4 questions at the beginning of the seder; 13 questions at the end (Ehad Mi Yode‘a); Two litanies in the haggadah: the Dayenu before the meal and Hodu after the meal. 2) Joshua Kulp, PhD, The Origins of the Seder and Haggadah, 2005, p2 Three main forces stimulated the rabbis to develop innovative seder ritual and to generate new, relevant exegeses to the biblical Passover texts: (1) the twin calamities of the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple and the Bar-Kokhba revolt; (2) competition with emerging Christian groups; (3) assimilation of Greco-Roman customs and manners. 2nd Seder 3) David Galenson, PhD, Old Masters and Young Geniuses There have been two very different types of artist in the modern era…I call one of these methods aesthetically motivated experimentation, and the other conceptual execution. Artists who have produced experimental innovations have been motivated by aesthetic criteria: they have aimed at presenting visual perceptions. Their goals are imprecise… means that these artists rarely feel they have succeeded, and their careers are consequently often dominated by the pursuit of a single objective.