'Not by Bread Alone…': Food and Drink in the Rabbinic Seder and In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520)

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520) The Artist as Universal Man and Individual Genius By Susan Behrends Frank, Ph.D. Associate Curator for Research The Phillips Collection What are the new ideas behind the Italian High Renaissance? • Commitment to monumental interpretation of form with the human figure at center stage • Integration of form and space; figures actually occupy space • New medium of oil allows for new concept of luminosity as light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in a manner that allows form to be constructed in space in a new way • Physiological aspect of man developed • Psychological aspect of man explored • Forms in action • Dynamic interrelationship of the parts to the whole • New conception of the artist as the universal man and individual genius who is creative in multiple disciplines Michelangelo The Artists of the Italian High Renaissance Considered Universal Men and Individual Geniuses Raphael- Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci- Self-Portrait Michelangelo- Pietà- 1498-1500 St. Peter’s, Rome Leonardo da Vinci- Mona Lisa (Lisa Gherardinidi Franceso del Giacondo) Raphael- Sistine Madonna- 1513 begun c. 1503 Gemäldegalerie, Dresden Louvre, Paris Leonardo’s Notebooks Sketches of Plants Sketches of Cats Leonardo’s Notebooks Bird’s Eye View of Chiana Valley, showing Arezzo, Cortona, Perugia, and Siena- c. 1502-1503 Storm Breaking Over a Valley- c. 1500 Sketch over the Arno Valley (Landscape with River/Paesaggio con fiume)- 1473 Leonardo’s Notebooks Studies of Water Drawing of a Man’s Head Deluge- c. 1511-12 Leonardo’s Notebooks Detail of Tank Sketches of Tanks and Chariots Leonardo’s Notebooks Flying Machine/Helicopter Miscellaneous studies of different gears and mechanisms Bat wing with proportions Leonardo’s Notebooks Vitruvian Man- c. -

Thetorah -Com

6t9t2U2U I ne Paraoox oI Pesacn :inenr - | ne I oran.com TheTorah -com The Paradox of Pesach Sheni As a historical commemoration, Passover is tied to a specific date. Nevertheless, the Torah gives a make-up date for bringing the offering a month later. Gerim, non- Israelites living among Israelites as equals, are also allowed to bring this offering, even though it wasn)t their ancestors who were freed. How do we make sense of these anomalies? Prof. Steven Fraade u* ntrs .!i.aitrir! i'irir;ri{,r I t i I I 5* \} - A Fixed Lunar-Calendrical Commemoration: A fter explaining to Moses how the Israelites should perform the Passover I I ritual in order to avoid being killed during the plague of the firstborn, YHWH endswith: El? nll triri nin] T:rr ntDur ExodD:14 This day shallbe to you one of ;r:;r-! rf inx onirrlr firpr5 remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a hltns'//unrnrr thelnrah enm/artinlc/the-naradav-nf-nceanh-ehpni 1 111 6t9t2U2t) I he Paradox ot Pesach shent - | ne loran.com .r;lilT tr?i9 ni?l;| tr)!I-r1' festival to YHWH throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. Moses then passes the message along to the elders of Israel, expanding on this point: 'D:r' niDu' Exod'12:2t+ l?:Tn n$ trR"lDt?l You shall observe this as an .o?ip ru Tt;}'r! il4);'rrn institution for all time, for you and for ;'1):r' f':lqt? tli tNff '? i"l';r'l your descendants. -

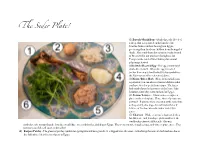

The Seder Plate

Te Seder Plate! (1) Zaroah/Shank Bone - Symbolizes the blood of a sheep that was painted on the lintels of the Israelite homes on their last night in Egypt, protecting their firstborn children from the angel of death. Also symbolizes the sacrifice for the festival of Passover that our ancestors brought to the Temple in the land of Israel during this annual pilgrimage festival. (2)Beitzah/Roasted Egg - The egg is round and symbolizes rebirth. When the egg is roasted (rather than simply hard boiled) it also symbolizes the Passover sacrifice referenced above. (3)Maror/Bitter Herb - Here, horseradish paste is pictured; you can also use horseradish root that you have sliced or peeled into strips. The bitter herb symbolizes the bitterness of the lives of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. (4) Potato/Lettuce - Often lettuce occupies a place on the seder plate. Here, slices of potato are pictured. If potato, these are eaten at the same time as the parsley, also dipped in salt water (6) or if lettuce, at the time when the bitter herb (3) is eaten. (5) Charoset - While everyone’s charoset looks a bit different - and Jewish people from all over the world make charoset differently - this mix symbolizes the mortar that the Israelites would have used with bricks, building in Egypt. This is often a mix of apples, nuts, and wine or grape juice. This sweetness is a beloved taste of the seder! (6) Karpas/Parsley - The green of parsley symbolizes springtime and new growth. It is dipped into salt water, symbolizing the tears of the Israelites due to the difficulty of their lives in slavery in Egypt.. -

Jessica Canchola the Last Supper

Leonardo da Vinci Research by: Jessica Canchola South Mountain Community College Who is Leonardo da Mona Lisa Conclusions Vinci ? The Last Supper The artist Leonardo da Vinci was well-known as One of Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous Another of his most famous paintings was “Last one of the greatest painters. Today, he is known paintings in the world is Mona Lisa. It was Supper”. The Last Supper was created around Leonardo da Vinci's countless projects best for his art, which includes the Mona Lisa created between 1503 and 1519, while Leonardo 1495 to 1498. The mural is one of the best-known throughout various fields of Arts and and The Last Supper, two paintings that are still was living in Florence, and it is now located in Christian arts. The Last Supper is a Renaissance Sciences helped introduce to modern among the most famous and admired in the the Louvre Museum in Paris. The Mona Lisa's masterpiece who has survived and thrived intact society on ongoing ideas for fields such world. He was born on May 15, 1452, in a mysterious smile has enchanted dozens of over the centuries. It was commenced by Duke as anatomy or geology, demonstrating the farmhouse near the Tuscan village of Anchiano viewers, but despite extensive research by art Ludovico Sforza for the refectory of the extent to which Da Vinci had an impact. in Tuscany, Italy. Leonardo da Vinci's parents historians, the identity of the woman depicted monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, were not married when he was born. -

(Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014

7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014 7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Rabbi Marcelo Kormis 30 Sessions Notes to Parents: This curriculum contains the knowledge, skills and attitude Jewish students are expected to learn. It provides the learning objectives that students are expected to meet; the units and lessons that teachers teach; the books, materials, technology and readings used in a course; and the assessments methods used to evaluate student learning. Some units have a large amount of material that on a given year may be modified in consideration of the Jewish calendar, lost school days due to weather (snow days), and give greater flexibility to the teacher to accommodate students’ pre-existing level of knowledge and skills. Page 1 of 16 7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014 Part 1 Musaguim – A Vocabulary of Jewish Life 22 Sessions The 7th grade curriculum will focus on basic musaguim of Jewish life. These musaguim cover the different aspects and levels of Jewish life. They can be divided into 4 concentric circles: inner circle – the day of a Jew, middle circle – the week of a Jew, middle outer circle – the year of a Jew, outer circle – the life of a Jew. The purpose of this course is to teach students about the different components of a Jewish day, the centrality of the Shabbat, the holidays and the stages of the life cycle. Focus will be placed on the Jewish traditions, rituals, ceremonies, and celebrations of each concept. Lifecycle events Jewish year Week - Shabbat Day Page 2 of 16 7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014 Unit 1: The day of a Jew: 6 sessions, 45 minute each. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

The Last Supper Seen Six Ways by Louis Inturrisi the New York Times, March 23, 1997

1 Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper, in a former convent refectory that is now a museum. The Last Supper Seen Six Ways By Louis Inturrisi The New York Times, March 23, 1997 When I was 9 years old, I painted the Last Supper. I did it on the dining room table at our home in Connecticut on Saturday afternoon while my mother ironed clothes and hummed along with the Texaco. Metropolitan Operative radio broadcast. It took me three months to paint the Last Supper, but when I finished and hung it on my mother's bedroom wall, she assured me .it looked just like Leonardo da Vinci's painting. It was supposed to. You can't go very wrong with a paint-by-numbers picture, and even though I didn't always stay within the lines and sometimes got the colors wrong, the experience left me with a profound respect for Leonardo's achievement and a lingering attachment to the genre. So last year, when the Florence Tourist Bureau published a list of frescoes of the Last Supper that are open to the public, I was immediately on their track. I had seen several of them, but never in sequence. During the Middle Ages the ultima cena—the final supper Christ shared with His disciples before His arrest and crucifixion—was part of any fresco cycle that told His life story. But in the 15th century the Last Supper began to appear independently, especially in the refectories, or dining halls, of the convents and monasteries of the religious orders founded during the Middle Ages. -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

MALTESE E-NEWLETTER 263 April 2919 1

MALTESE E-NEWLETTER 263 April 2919 1 MALTESE E-NEWLETTER 263 April 2919 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE TO THE READERS OF THE MALTESE JOURNAL Dear Frank, I am really grateful for your kind gesture to dedicate such coverage to my inauguration in your newsletter. I fondly remember your participation in the Council for Maltese Living Abroad, where we tried to do our best to strengthen relations between the Maltese diaspora and the Motherland. I strongly believe that the Maltese abroad are still an untapped source which we could use help us achieve the objectives I spoke about in my inaugural speech. Please convey my heartfelt best wishes to all your readers and may we all keep Malta's name in our hearts. H.E. Dr.George Vella . President George Vella visits Bishop of Gozo Mgr Mario Grech As part of his first visit to Gozo this Saturday, the President George Vella, together with his wife Miriam Vella, paid a visit to the Bishop of Gozo Mgr Mario Grech, in the Bishop’s Curia, Victoria, where they met also by the Curia and the College of Chaplains. The Bishop congratulated Dr Vella on his appointment and presented him with a copy of the Bible. Bishop Grech said, “from my heart I trust that despite the many commitments, that you will manage to find some time for personal prayer.”Later, the President was also expected to visit the National Shrine of Our Lady of Ta’ Pinu. Also present at the visit was the Minister for Gozo Dr. Justyne Caruana. 2 MALTESE E-NEWLETTER 263 April 2919 Malta: The Country that was Awarded the George Cross April 15, 1942 days and nights - with thousands of tonnes of bombs dropped on airfields, naval bases, The Mediterranean island endured more than homes and offices. -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

Scrovegni Chapel 1 Scrovegni Chapel

Scrovegni Chapel 1 Scrovegni Chapel The Scrovegni Chapel, or Cappella degli Scrovegni, also known as the Arena Chapel, is a church in Padua, Veneto, Italy. It contains a fresco cycle by Giotto, completed about 1305, that is one of the most important masterpieces of Western art. The church was dedicated to Santa Maria della Carità at the Feast of the Annunciation, 1305. Giotto's fresco cycle focuses on the life of the Virgin Mary and celebrates her role in human salvation. The chapel is also known as the Arena Chapel because it was built on land purchased by Enrico Scrovegni that abutted the site of a Roman arena. This space is where an open-air procession and sacred representation of the Annunciation to the Virgin had been played out for a generation before the chapel was built. A motet by Marchetto da Padova appears to have been composed for the dedication on March 25, 1305.[1] The chapel was commissioned by Enrico Scrovegni, whose family fortune was made through the practice of usury, which at this time meant charging interest when loaning money, a sin so grave that it resulted in exclusion from the Christian sacraments.[2] Built on family estate, it is often suggested that Enrico built the chapel in penitence for his father's sins and for Capella degli Scrovegni absolution for his own. Enrico's father Reginaldo degli Scrovegni is the usurer encountered by Dante in the Seventh Circle of Hell. A recent study suggests that Enrico himself was involved in usurious practices and that the chapel was intended as restitution for his own sins.[3] Enrico's tomb is in the apse, and he is also portrayed in the Last Judgment presenting a model of the chapel to the Virgin. -

Passover Seder Plate Guide

From The Shiksa in the Kitchen Recipe Archives http://www.theshiksa.com PASSOVER SEDER PLATE BLESSINGS Here is a brief explanation of the Seder plate blessings and their meaning. Share with your children as you decorate your Homemade Passover Seder Plate! Beitzah - Egg Blessing: The hard-boiled egg serves as a reminder of the “Festival Offering.” It is dipped in saltwater and eaten at the beginning of the Seder Meal. It symbolizes both the celebration of the festivals and the mourning of the loss of the Temple in Jerusalem. Its round shape also represents the cycle of life and things eventually returning to where they began – a hope that the Temple will one day be restored in Jerusalem. Maror - Bitter Herb Blessing: Usually made of romaine lettuce or endive leaves and ground horseradish, it is dipped in the charoset and eaten. The maror represents the “bitterness” and hard labor endured by the Jewish people while slaves in Egypt. It also represents the bitterness of the Exile. It serves as a reminder of the unhappiness that inspires us to improve our lives. Zeroah - Shank Bone: The shank bone, with most of the meat removed, is not eaten but instead serves as a reminder of the lamb, or young goat, that was offered to God in the Holy Temple on the night the Jewish people fled from Egypt. It symbolizes God’s love when “passing over” the houses of the Jews on the night of Exodus, when the Egyptian first born died. It represents the ability to exceed our limitations. Charoset – Mortar Blessing: The charoset, a paste-like mixture of fruit, nuts and wine, is a symbol of the mortar used by the Jewish slaves in the construction of the Pharaoh’s pyramids.