The Age of Pleasure and Enlightenment European Art of the Eighteenth Century Increasingly Emphasized Civility, Elegance, Comfor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520)

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520) The Artist as Universal Man and Individual Genius By Susan Behrends Frank, Ph.D. Associate Curator for Research The Phillips Collection What are the new ideas behind the Italian High Renaissance? • Commitment to monumental interpretation of form with the human figure at center stage • Integration of form and space; figures actually occupy space • New medium of oil allows for new concept of luminosity as light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in a manner that allows form to be constructed in space in a new way • Physiological aspect of man developed • Psychological aspect of man explored • Forms in action • Dynamic interrelationship of the parts to the whole • New conception of the artist as the universal man and individual genius who is creative in multiple disciplines Michelangelo The Artists of the Italian High Renaissance Considered Universal Men and Individual Geniuses Raphael- Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci- Self-Portrait Michelangelo- Pietà- 1498-1500 St. Peter’s, Rome Leonardo da Vinci- Mona Lisa (Lisa Gherardinidi Franceso del Giacondo) Raphael- Sistine Madonna- 1513 begun c. 1503 Gemäldegalerie, Dresden Louvre, Paris Leonardo’s Notebooks Sketches of Plants Sketches of Cats Leonardo’s Notebooks Bird’s Eye View of Chiana Valley, showing Arezzo, Cortona, Perugia, and Siena- c. 1502-1503 Storm Breaking Over a Valley- c. 1500 Sketch over the Arno Valley (Landscape with River/Paesaggio con fiume)- 1473 Leonardo’s Notebooks Studies of Water Drawing of a Man’s Head Deluge- c. 1511-12 Leonardo’s Notebooks Detail of Tank Sketches of Tanks and Chariots Leonardo’s Notebooks Flying Machine/Helicopter Miscellaneous studies of different gears and mechanisms Bat wing with proportions Leonardo’s Notebooks Vitruvian Man- c. -

Prints from Private Collections in New England, 9 June – 10 September 1939, No

Bernardo Bellotto (Venice 1721 - Warsaw 1780) The Courtyard of the Fortress of Königstein with the Magdalenenburg oil on canvas 49.7 x 80.3 cm (19 ⁵/ x 31 ⁵/ inches) Bernardo Bellotto was the nephew of the celebrated Venetian view painter Canaletto, whose studio he entered around 1735. He so thoroughly assimilated the older painter’s methods and style that the problem of attributing certain works to one painter or the other continues to the present day. Bellotto’s youthful paintings exhibit a high standard of execution and handling, however, by about 1740 the intense effects of light, shade, and color in his works anticipate his distinctive mature style and eventual divergence from the manner of his teacher. His first incontestable works are those he created during his Italian travels in the 1740s. In the period 1743-47 Bellotto traveled throughout Italy, first in central Italy and later in Lombardy, Piedmont, and Verona. For many, the Italian veduteare among his finest works, but it was in the north of Europe that he enjoyed his greatest success and forged his reputation. In July 1747, in response to an official invitation from the court of Dresden, Bellotto left Venice forever. From the moment of his arrival in the Saxon capital, he was engaged in the service of Augustus III, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, and of his powerful prime minister, Count Heinrich von Brühl. In 1748 the title of Court Painter was officially conferred on the artist, and his annual salary was the highest ever paid by the king to a painter. -

Kingston Lacy Illustrated List of Pictures K Introduction the Restoration

Kingston Lacy Illustrated list of pictures Introduction ingston Lacy has the distinction of being the however, is a set of portraits by Lely, painted at K gentry collection with the earliest recorded still the apogee of his ability, that is without surviving surviving nucleus – something that few collections rival anywhere outside the Royal Collection. Chiefly of any kind in the United Kingdom can boast. When of members of his own family, but also including Ralph – later Sir Ralph – Bankes (?1631–1677) first relations (No.16; Charles Brune of Athelhampton jotted down in his commonplace book, between (1630/1–?1703)), friends (No.2, Edmund Stafford May 1656 and the end of 1658, a note of ‘Pictures in of Buckinghamshire), and beauties of equivocal my Chamber att Grayes Inne’, consisting of a mere reputation (No.4, Elizabeth Trentham, Viscountess 15 of them, he can have had little idea that they Cullen (1640–1713)), they induced Sir Joshua would swell to the roughly 200 paintings that are Reynolds to declare, when he visited Kingston Hall at Kingston Lacy today. in 1762, that: ‘I never had fully appreciated Sir Peter That they have done so is due, above all, to two Lely till I had seen these portraits’. later collectors, Henry Bankes II, MP (1757–1834), Although Sir Ralph evidently collected other – and his son William John Bankes, MP (1786–1855), but largely minor pictures – as did his successors, and to the piety of successive members of the it was not until Henry Bankes II (1757–1834), who Bankes family in preserving these collections made the Grand Tour in 1778–80, and paid a further virtually intact, and ultimately leaving them, in the visit to Rome in 1782, that the family produced astonishingly munificent bequest by (Henry John) another true collector. -

The Marriage Contract in Fine Art

The Marriage Contract in Fine Art BENJAMIN A. TEMPLIN* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 45 II. THE ARTIST'S INTERPRETATION OF LAW ...................................... 52 III. THE ARNOLFINI MARRIAGE: CLANDESTINE MARRIAGE CEREMONY OR BETROTHAL CONTRACT? .............................. ........................ .. 59 IV. PRE-CONTRACTUAL SEX AND THE LAWYER AS PROBLEM SOLVER... 69 V. DOWRIES: FOR LOVE OR MONEY? ........................ ................ .. .. 77 VI. WILLIAM HOGARTH: SATIRIC INDICTMENT OF ARRANGED MARRIAGES ...................................................................................... 86 VII. GREUZE: THE CIVIL MARRIAGE CONTRACT .................................. 93 VIII.NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY COMPARISONS ................ 104 LX . C ONCLUSION ..................................................................................... 106 I. INTRODUCTION From the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment, several European and English artists produced paintings depicting the formation of a marriage contract.' The artwork usually portrays a couple-sometimes in love, some- * Associate Professor, Thomas Jefferson School of Law. For their valuable assis- tance, the author wishes to thank Susan Tiefenbrun, Chris Rideout, Kathryn Sampson, Carol Bast, Whitney Drechsler, Ellen Waldman, David Fortner, Sandy Contreas, Jane Larrington, Julie Kulas, Kara Shacket, and Dessa Kirk. The author also thanks the organizers of the Legal Writing Institute's 2008 Summer Writing Workshop -

Morgan's Holdings of Eighteenth Century Venetian Drawings Number

Press Contacts Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] l Alanna Schindewolf 212.590.0311, [email protected] NEW MORGAN EXHIBITION EXPLORES ART IN 18TH-CENTURY VENICE WITH MORE THAN 100 DRAWINGS FROM THE MUSEUM’S RENOWNED HOLDINGS Tiepolo, Guardi, and Their World: Eighteenth-Century Venetian Drawings September 27, 2013–January 5, 2014 **Press Preview: Thursday, September 26, 2013, 10:00–11:30 a.m.** RSVP: (212) 590-0393, [email protected] New York, NY, September 3, 2013—The eighteenth century witnessed Venice’s second Golden Age. Although the city was no longer a major political power, it reemerged as an artistic capital, with such gifted artists as Giambattista Tiepolo, his son Domenico, Canaletto, and members of the Guardi family executing important commissions from the church, nobility, and bourgeoisie, while catering to foreign travelers and bringing their talents to other Italian cities and even north of the Alps. Drawn entirely from the Morgan’s collection of eighteenth-century Venetian drawings—one of Giambattista Tiepolo (1696–1770) Psyche Transported to Olympus the world’s finest—Tiepolo, Guardi, and Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk Gift of Lore Heinemann, in memory of her husband, Dr. Rudolf Their World chronicles the vitality and J. Heinemann, 1997.27 All works: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York originality of an incredibly vibrant period. The All works: Photography by Graham S. Haber exhibition will be on view from September 27, 2013–January 5, 2014. “In the eighteenth century, as the illustrious history of the thousand-year-old Venetian Republic was coming to a close, the city was favored with an array of talent that left a lasting mark on western art,” said William M. -

Jessica Canchola the Last Supper

Leonardo da Vinci Research by: Jessica Canchola South Mountain Community College Who is Leonardo da Mona Lisa Conclusions Vinci ? The Last Supper The artist Leonardo da Vinci was well-known as One of Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous Another of his most famous paintings was “Last one of the greatest painters. Today, he is known paintings in the world is Mona Lisa. It was Supper”. The Last Supper was created around Leonardo da Vinci's countless projects best for his art, which includes the Mona Lisa created between 1503 and 1519, while Leonardo 1495 to 1498. The mural is one of the best-known throughout various fields of Arts and and The Last Supper, two paintings that are still was living in Florence, and it is now located in Christian arts. The Last Supper is a Renaissance Sciences helped introduce to modern among the most famous and admired in the the Louvre Museum in Paris. The Mona Lisa's masterpiece who has survived and thrived intact society on ongoing ideas for fields such world. He was born on May 15, 1452, in a mysterious smile has enchanted dozens of over the centuries. It was commenced by Duke as anatomy or geology, demonstrating the farmhouse near the Tuscan village of Anchiano viewers, but despite extensive research by art Ludovico Sforza for the refectory of the extent to which Da Vinci had an impact. in Tuscany, Italy. Leonardo da Vinci's parents historians, the identity of the woman depicted monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, were not married when he was born. -

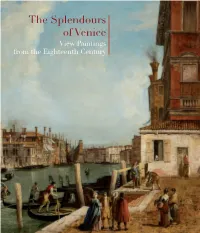

The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century the Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century

The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century Valentina Rossi and Amanda Hilliam DE LUCA EDITORI D’ARTE The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century Lampronti Gallery 1-24 December 2014 9.30 - 6 pm Exhibition curated by Acknowledgements Amanda Hilliam Marcella di Martino, Emanuela Tarizzo, Barbara De Nipoti, the staff of Valentina Rossi Itaca Transport, the staff of Simon Jones Superfreight. Catalogue edited by Amanda Hilliam Valentina Rossi Photography Mauro Coen Matthew Hollow LAMPRONTI GALLERY 44 Duke Street, St James’s London SW1Y 6DD Via di San Giacomo 22 00187 Roma [email protected] [email protected] p. 2: Francesco Guardi, The lagoon with the Forte di S. Andrea, cat. 20, www.cesarelampronti.com detail his exhibition and catalogue commemorates the one-hundred-year anniversary of Lampronti Gallery, founded in 1914 by my Grandfather and now one of the foremost galleries specialising in Italian Old TMaster paintings in the United Kingdom. We have, over the years, developed considerable knowledge and expertise in the field of vedute, or view paintings, and it therefore seemed fitting that this centenary ex- hibition be dedicated to our best examples of this great tradition, many of which derive from important pri- vate collections and are published here for the first time. More precisely, the exhibition brings together a fine selection of views of Venice, a city whose romantic canals and quality of light were never represented with greater sensitivity or technical brilliance than during the eigh- teenth century. -

The Last Supper Seen Six Ways by Louis Inturrisi the New York Times, March 23, 1997

1 Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper, in a former convent refectory that is now a museum. The Last Supper Seen Six Ways By Louis Inturrisi The New York Times, March 23, 1997 When I was 9 years old, I painted the Last Supper. I did it on the dining room table at our home in Connecticut on Saturday afternoon while my mother ironed clothes and hummed along with the Texaco. Metropolitan Operative radio broadcast. It took me three months to paint the Last Supper, but when I finished and hung it on my mother's bedroom wall, she assured me .it looked just like Leonardo da Vinci's painting. It was supposed to. You can't go very wrong with a paint-by-numbers picture, and even though I didn't always stay within the lines and sometimes got the colors wrong, the experience left me with a profound respect for Leonardo's achievement and a lingering attachment to the genre. So last year, when the Florence Tourist Bureau published a list of frescoes of the Last Supper that are open to the public, I was immediately on their track. I had seen several of them, but never in sequence. During the Middle Ages the ultima cena—the final supper Christ shared with His disciples before His arrest and crucifixion—was part of any fresco cycle that told His life story. But in the 15th century the Last Supper began to appear independently, especially in the refectories, or dining halls, of the convents and monasteries of the religious orders founded during the Middle Ages. -

Warsaw University Library Tanks and Helicopters

NOWY ŚWIAT STREET Nearby: – military objects. There is an interesting outdoor able cafes and restaurants, as well as elegant UJAZDOWSKIE AVENUE Contemporary Art – a cultural institution and THE WILANÓW PARK exhibition making it possible to admire military boutiques and shops selling products of the an excellent gallery. Below the escarpment, AND PALACE COMPLEX The Mikołaj Kopernik Monument The Warsaw University Library tanks and helicopters. world’s luxury brands. The Ujazdowski Park east of the Castle, there is the Agricola Park (Pomnik Mikołaja Kopernika) (Biblioteka Uniwersytecka w Warszawie) (Park Ujazdowski) and the street of the same name, where street ul. St. Kostki Potockiego 10/16 ul. Dobra 56/66, www.buw.uw.edu.pl The National Museum The St. Alexander’s Church gas lamps are hand lit by lighthouse keepers tel. +48 22 544 27 00 One of the best examples of modern architecture (Muzeum Narodowe) (Kościół św. Aleksandra) just before the dusk and put down at dawn. www.wilanow-palac.art.pl in the Polish capital. In the underground of this Al. Jerozolimskie 3 ul. Książęca 21, www.swaleksander.pl It used to be the summer residence of Jan interesting building there is an entertainment tel. +48 22 621 10 31 A classicist church modelled on the Roman The Botanical Garden III Sobieski, and then August II as well as centre (with bowling, billiards, climbing wall) www.mnw.art.pl Pantheon. It was built at the beginning of the of the Warsaw University the most distinguished aristocratic families. and on the roof there is one of the prettiest One of the most important cultural institutions 19th c. -

2021 Sacred Hear Nesletter

Benedictine Monastery, 5 Mackerston Place, Largs KA30 8BY, SCOTLAND, Tel. 01475 687 320 [email protected] Solemnity of the Most Sacred Heart June 2021 Dear Friends, When we were dead through sin, God brought us to life again in Christ, -because He loved us with so great a love. That He might reveal for all ages to come the immeasurable riches of his grace. - because He loved us with so great a love. (Responsory for the Office of Readings, The Most Sacred Heart of Jesus: Ephesians 2:5,4,7) The Solemnity of the Sacred Heart is a time of remembrance and celebration of the everlasting love of God in the Sacred Heart. The whole of the Church’s celebration from Easter to this feast has been the victory of the Sacred Heart. We celebrated the Paschal mystery of God’s redemptive love in Christ Jesus, when Love Incarnate gave Himself for us unto death, reconciling us to His Father and making us co-heirs with him; when His bride the Church, was born from His pierced Heart from which the Sacramental life of the Church flows; when by His resurrection, love triumphed over death; then He ascended into heaven to prepare a place for us to be with Him forever. He then sent us His Spirit of Love to be our teacher, guide and sanctifier, to make potent and fruitful in our souls His redemptive sacrifice; pouring upon us the streams of living water from His pierced Heart so that our hearts too will flow with that water. On the Octave of Easter the Sacred Heart enveloped His Church in the rays of His merciful Heart inviting us to meditate on His inexhaustible mercy, His greatest attribute. -

Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals February 20, 2011 - May 30, 2011

Updated Friday, February 11, 2011 | 3:41:22 PM Last updated Friday, February 11, 2011 Updated Friday, February 11, 2011 | 3:41:22 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals February 20, 2011 - May 30, 2011 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required(*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. File Name: 2866-103.jpg Title Title Section Raw File Name: 2866-103.jpg Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia (Iconongraphic Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia (Iconongraphic Representation of the Illustrious City of Venice), 1729 Display Order Representation of the Illustrious City of Venice), 1729 etching and engraving on twenty joined sheets of laid paper etching and engraving on twenty joined sheets of laid paper 148.5 x 264.2 -

Gallery Painting in Italy, 1700-1800

Gallery Painting in Italy, 1700-1800 The death of Gian Gastone de’ Medici, the last Medici Grand Duke of Tuscany, in 1737, signaled the end of the dynasties that had dominated the Italian political landscape since the Renaissance. Florence, Milan, and other cities fell under foreign rule. Venice remained an independent republic and became a cultural epicenter, due in part to foreign patronage and trade. Like their French contemporaries, Italian artists such as Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Francesco Guardi, and Canaletto, favored lighter colors and a fluid, almost impressionistic handling of paint. Excavations at the ancient sites of Herculaneum and Pompeii spurred a flood of interest in classical art, and inspired new categories of painting, including vedute or topographical views, and capricci, which were largely imaginary depictions of the urban and rural landscape, often featuring ruins. Giovanni Paolo Pannini’s paintings showcased ancient and modern architectural settings in the spirit of the engraver, Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Music and theater flourished with the popularity of the piano and the theatrical arts. The commedia dell’arte, an improvisational comedy act with stock characters like Harlequin and Pulcinella, provided comic relief in the years before the Napoleonic War, and fueled the production of Italian genre painting, with its unpretentious scenes from every day life. The Docent Collections Handbook 2007 Edition Francesco Solimena Italian, 1657-1747, active in Naples The Virgin Receiving St. Louis Gonzaga, c. 1720 Oil on canvas Bequest of John Ringling, 1936, SN 165 Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini Italian, 1675-1741, active in Venice The Entombment, 1719 Oil on canvas Bequest of John Ringling, 1936, SN 176 Amid the rise of such varieties of painting as landscape and genre scenes, which previously had been considered minor categories in academic circles, history painting continued to be lauded as the loftiest genre.