The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century the Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

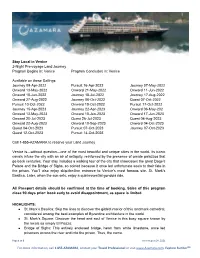

Stay Local in Venice 2-Night Pre-Voyage Land Journey Program Begins In: Venice Program Concludes In: Venice

Stay Local in Venice 2-Night Pre-voyage Land Journey Program Begins in: Venice Program Concludes in: Venice Available on these Sailings: Journey 09-Apr-2022 Pursuit 16-Apr-2022 Journey 07-May-2022 Onward 13-May-2022 Onward 21-May-2022 Onward 11-Jun-2022 Onward 18-Jun-2022 Journey 18-Jul-2022 Journey 17-Aug-2022 Onward 27-Aug-2022 Journey 06-Oct-2022 Quest 07-Oct-2022 Pursuit 10-Oct-2022 Onward 10-Oct-2022 Pursuit 17-Oct-2022 Journey 15-Apr-2023 Journey 22-Apr-2023 Onward 06-May-202 Onward 13-May-2023 Onward 10-Jun-2023 Onward 17-Jun-2023 Onward 20-Jul-2023 Quest 26-Jul-2023 Quest 04-Aug-2023 Onward 22-Aug-2023 Onward 10-Sep-2023 Onward 04-Oct-2023 Quest 04-Oct-2023 Pursuit 07-Oct-2023 Journey 07-Oct-2023 Quest 12-Oct-2023 Pursuit 14-Oct-2023 Call 1-855-AZAMARA to reserve your Land Journey Venice is—without question—one of the most beautiful and unique cities in the world. Its iconic canals infuse the city with an air of antiquity, reinforced by the presence of ornate palazzos that go back centuries. Your stay includes a walking tour of the city that showcases the great Doge’s Palace and the Bridge of Sighs, so coined because it once led unfortunate souls to their fate in the prison. You’ll also enjoy skip-the-line entrance to Venice’s most famous site, St. Mark’s Basilica. Later, when the sun sets, enjoy a quintessential gondola ride. All Passport details should be confirmed at the time of booking. -

Suspension Bridges

Types of Bridges What are bridges used for? What bridges have you seen in real life? Where were they? Were they designed for people to walk over? Do you know the name and location of any famous bridges? Did you know that there is more than one type of design for bridges? Let’s take a look at some of them. Suspension Bridges A suspension bridge uses ropes, chains or cables to hold the bridge in place. Vertical cables are spaced out along the bridge to secure the deck area (the part that you walk or drive over to get from one side of the bridge to the other). Suspension bridges can cover large distances. Large pillars at either end of the waterways are connected with cables and the cables are secured, usually to the ground. Due to the variety of materials and the complicated design, suspension bridges are very expensive to build. Suspension Bridges The structure of suspension bridges has changed throughout the years. Jacob’s Creek Bridge in Pennsylvania was built in 1801. It was the first suspension bridge to be built using wrought iron chain suspensions. It was 21 metres long. If one single link in a chain is damaged, it weakens the whole chain which could lead to the collapse of the bridge. For this reason, wire or cable is used in the design of suspension bridges today. Even though engineer James Finlay promised that the bridge would stay standing for 50 years, it was damaged in 1825 and replaced in 1833. Suspension Bridges Akashi Kaiko Bridge, Japan The world’s longest suspension bridge is the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge in Japan. -

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Canal Grande (The Grand Canal)

Canal Grande (The Grand Canal) Night shot of the Canal Grande or Grand Canal of Venice, Italy The Canal Grande and the Canale della Giudecca are the two most important waterways in Venice. They undoubtedly fall into the category of one of the premier tourist attractions in Venice. The Canal Grande separates Venice into two distinct parts, which were once popularly referred to as 'de citra' and 'de ultra' from the point of view of Saint Mark's Basilica, and these two parts of Venice are linked by the Rialto bridge. The Rialto Bridge is the most ancient bridge in Venice.; it is completely made of stone and its construction dates back to the 16th century. The Canal Grande or the Grand Canal forms one of the major water-traffic corridors in the beautiful city of Venice. The most popular mode of public transportation is traveling by the water bus and by private water taxis. This canal crisscrosses the entire city of Venice, and it begins its journey from the lagoon near the train station and resembles a large S-shape through the central districts of the "sestiere" in Venice, and then comes to an end at the Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute near the Piazza San Marco. The major portion of the traffic of the city of Venice goes along the Canal Grande, and thus to avoid congestion of traffic there are already three bridges – the Ponte dei Scalzi, the Ponte dell'Accademia, and the Rialto Bridge, while another bridge is being constructed. The new bridge is designed by Santiago Calatrava, and it will link the train station to the Piazzale Roma. -

Morgan's Holdings of Eighteenth Century Venetian Drawings Number

Press Contacts Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] l Alanna Schindewolf 212.590.0311, [email protected] NEW MORGAN EXHIBITION EXPLORES ART IN 18TH-CENTURY VENICE WITH MORE THAN 100 DRAWINGS FROM THE MUSEUM’S RENOWNED HOLDINGS Tiepolo, Guardi, and Their World: Eighteenth-Century Venetian Drawings September 27, 2013–January 5, 2014 **Press Preview: Thursday, September 26, 2013, 10:00–11:30 a.m.** RSVP: (212) 590-0393, [email protected] New York, NY, September 3, 2013—The eighteenth century witnessed Venice’s second Golden Age. Although the city was no longer a major political power, it reemerged as an artistic capital, with such gifted artists as Giambattista Tiepolo, his son Domenico, Canaletto, and members of the Guardi family executing important commissions from the church, nobility, and bourgeoisie, while catering to foreign travelers and bringing their talents to other Italian cities and even north of the Alps. Drawn entirely from the Morgan’s collection of eighteenth-century Venetian drawings—one of Giambattista Tiepolo (1696–1770) Psyche Transported to Olympus the world’s finest—Tiepolo, Guardi, and Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk Gift of Lore Heinemann, in memory of her husband, Dr. Rudolf Their World chronicles the vitality and J. Heinemann, 1997.27 All works: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York originality of an incredibly vibrant period. The All works: Photography by Graham S. Haber exhibition will be on view from September 27, 2013–January 5, 2014. “In the eighteenth century, as the illustrious history of the thousand-year-old Venetian Republic was coming to a close, the city was favored with an array of talent that left a lasting mark on western art,” said William M. -

ART HISTORY of VENICE HA-590I (Sec

Gentile Bellini, Procession in Saint Mark’s Square, oil on canvas, 1496. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice ART HISTORY OF VENICE HA-590I (sec. 01– undergraduate; sec. 02– graduate) 3 credits, Summer 2016 Pratt in Venice––Pratt Institute INSTRUCTOR Joseph Kopta, [email protected] (preferred); [email protected] Direct phone in Italy: (+39) 339 16 11 818 Office hours: on-site in Venice immediately before or after class, or by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION On-site study of mosaics, painting, architecture, and sculpture of Venice is the primary purpose of this course. Classes held on site alternate with lectures and discussions that place material in its art historical context. Students explore Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque examples at many locations that show in one place the rich visual materials of all these periods, as well as materials and works acquired through conquest or collection. Students will carry out visually- and historically-based assignments in Venice. Upon return, undergraduates complete a paper based on site study, and graduate students submit a paper researched in Venice. The Marciana and Querini Stampalia libraries are available to all students, and those doing graduate work also have access to the Cini Foundation Library. Class meetings (refer to calendar) include lectures at the Università Internazionale dell’ Arte (UIA) and on-site visits to churches, architectural landmarks, and museums of Venice. TEXTS • Deborah Howard, Architectural History of Venice, reprint (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003). [Recommended for purchase prior to departure as this book is generally unavailable in Venice; several copies are available in the Pratt in Venice Library at UIA] • David Chambers and Brian Pullan, with Jennifer Fletcher, eds., Venice: A Documentary History, 1450– 1630 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001). -

Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals February 20, 2011 - May 30, 2011

Updated Friday, February 11, 2011 | 3:41:22 PM Last updated Friday, February 11, 2011 Updated Friday, February 11, 2011 | 3:41:22 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals February 20, 2011 - May 30, 2011 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required(*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. File Name: 2866-103.jpg Title Title Section Raw File Name: 2866-103.jpg Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia (Iconongraphic Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia (Iconongraphic Representation of the Illustrious City of Venice), 1729 Display Order Representation of the Illustrious City of Venice), 1729 etching and engraving on twenty joined sheets of laid paper etching and engraving on twenty joined sheets of laid paper 148.5 x 264.2 -

Press Notice Exhibitions 2010

EXHIBITIONS AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY 2010 PRESS NOTICE MAJOR EXHIBITION PAINTING HISTORY: DELAROCHE AND LADY JANE GREY 24 February – 23 May 2010 Sainsbury Wing Admission charge Paul Delaroche was one of the most famous French painters of the early 19th century, with his work receiving wide international acclaim during his lifetime. Today Delaroche is little known in the UK – the aim of this exhibition is to return attention to a major painter who fell from favour soon after his death. Delaroche specialised in large historical tableaux, frequently of scenes from English history, characterised by close attention to fine detail and often of a tragic nature. Themes of imprisonment, execution and martyrdom Paul Delaroche, The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, 1833 © The National Gallery, London were of special interest to the French after the Revolution. The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (National Gallery, London), Delaroche’s depiction of the 1554 death of the 17-year-old who had been Queen of England for just nine days, created a sensation when first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1834. Monumental in scale, poignant in subject matter and uncanny in its intense realism, it drew amazed crowds, as it still does today in London. This exhibition will, for the first time in the UK, trace Delaroche’s career and allow this iconic painting to be seen in the context of the works which made his reputation, such as Marie Antoinette before the Tribunal (1851, The Forbes Collection, New York). Together with preparatory and comparative prints and drawings for Lady Jane Grey on loan from collections across Europe, it will explore the artist’s notion of theatricality and his ability to capture the psychological moment of greatest intensity which culminated in Lady Jane Grey. -

Gallery Painting in Italy, 1700-1800

Gallery Painting in Italy, 1700-1800 The death of Gian Gastone de’ Medici, the last Medici Grand Duke of Tuscany, in 1737, signaled the end of the dynasties that had dominated the Italian political landscape since the Renaissance. Florence, Milan, and other cities fell under foreign rule. Venice remained an independent republic and became a cultural epicenter, due in part to foreign patronage and trade. Like their French contemporaries, Italian artists such as Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Francesco Guardi, and Canaletto, favored lighter colors and a fluid, almost impressionistic handling of paint. Excavations at the ancient sites of Herculaneum and Pompeii spurred a flood of interest in classical art, and inspired new categories of painting, including vedute or topographical views, and capricci, which were largely imaginary depictions of the urban and rural landscape, often featuring ruins. Giovanni Paolo Pannini’s paintings showcased ancient and modern architectural settings in the spirit of the engraver, Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Music and theater flourished with the popularity of the piano and the theatrical arts. The commedia dell’arte, an improvisational comedy act with stock characters like Harlequin and Pulcinella, provided comic relief in the years before the Napoleonic War, and fueled the production of Italian genre painting, with its unpretentious scenes from every day life. The Docent Collections Handbook 2007 Edition Francesco Solimena Italian, 1657-1747, active in Naples The Virgin Receiving St. Louis Gonzaga, c. 1720 Oil on canvas Bequest of John Ringling, 1936, SN 165 Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini Italian, 1675-1741, active in Venice The Entombment, 1719 Oil on canvas Bequest of John Ringling, 1936, SN 176 Amid the rise of such varieties of painting as landscape and genre scenes, which previously had been considered minor categories in academic circles, history painting continued to be lauded as the loftiest genre. -

How to Tackle Flooding in Venice What Are the Institutional and Material

How to tackle flooding in Venice What are the institutional and material causes of MOSE’s failure? Master course: Environmental and Infrastructure Planning 11/06/2018 Student Supervisor Nicola Belafatti F.M.G. (Ferry) Van Kann s3232425 [email protected] University of Groningen Faculty of Spatial Sciences Abstract Literature extensively discusses the role of different elements such as corruption and stakeholder involvement as drivers of megaprojects’ success and failure (among others: Flyvbjerg et al., 2002; Flyvbjerg 2011, 2014; Locatelli 2017; Pinto and Kharbanda 1996; Shenhar et al., 2002; Shore 2008; Tabish and Jha 2011; etc). Scholars analyse reasons and incentives leading to the undertaking of public projects. The main consensus is that insufficient stakeholder involvement, processes lacking transparency and missing institutional checks are factors hindering the appropriate fulfilment of initial expectations and the realization of the project resulting in cost and time overruns (Flyvbjerg et al., 2002; Flyvbjerg 2014). The thesis tests the existing theories by linking them to a specific case study: Venice’s MOSE. The city of Venice and its lagoon have long been threatened by increasingly frequent floods, severely damaging the city’s historical and cultural heritage and disrupting people’s lives. The acqua alta phenomenon has considerably increased in scale and frequency throughout the last decade. The Italian government, in order to protect the lagoon and the city, launched in 2003 the construction of a mobile barrier called MOSE (MOdulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, Experimental Electromechanical Module) whose development had started back in the 1970s. The one-of-a-kind giant structure, known worldwide for its length and mass, has not yet been completed, though. -

“Talk” on Albanian Territories (1392–1402)

Doctoral Dissertation A Model to Decode Venetian Senate Deliberations: Pregadi “Talk” on Albanian Territories (1392–1402) By: Grabiela Rojas Molina Supervisors: Gerhard Jaritz and Katalin Szende Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department Central European University, Budapest In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies, Budapest, Hungary 2020 CEU eTD Collection To my parents CEU eTD Collection Table of Contents Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................. 1 List of Maps, Charts and Tables .......................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 A Survey of the Scholarship ........................................................................................................................... 8 a) The Myth of Venice ........................................................................................................................... 8 b) The Humanistic Outlook .................................................................................................................. 11 c) Chronicles, Histories and Diaries ..................................................................................................... 14 d) Albania as a Field of Study ............................................................................................................. -

The Age of Pleasure and Enlightenment European Art of the Eighteenth Century Increasingly Emphasized Civility, Elegance, Comfor

The Age of Pleasure and Enlightenment European art of the eighteenth century increasingly emphasized civility, elegance, comfort, and informality. During the first half of the century, the Rococo style of art and decoration, characterized by lightness, grace, playfulness, and intimacy, spread throughout Europe. Painters turned to lighthearted subjects, including inventive pastoral landscapes, scenic vistas of popular tourist sites, and genre subjects—scenes of everyday life. Mythology became a vehicle for the expression of pleasure rather than a means of revealing hidden truths. Porcelain and silver makers designed exuberant fantasies for use or as pure decoration to complement newly remodeled interiors conducive to entertainment and pleasure. As the century progressed, artists increasingly adopted more serious subject matter, often taken from classical history, and a simpler, less decorative style. This was the Age of Enlightenment, when writers and philosophers came to believe that moral, intellectual, and social reform was possible through the acquisition of knowledge and the power of reason. The Grand Tour, a means of personal enlightenment and an essential element of an upper-class education, was symbolic of this age of reason. The installation highlights the museum’s rich collection of eighteenth-century paintings and decorative arts. It is organized around four themes: Myth and Religion, Patrons and Collectors, Everyday Life, and The Natural World. These themes are common to art from different cultures and eras, and reveal connections among the many ways artists have visually expressed their cultural, spiritual, political, material, and social values. Myth and Religion Mythological and religious stories have been the subject of visual art throughout time.