Mahmoud Riad, May, 2009 Directed By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

The Arabic Roots of Jazz and Blues

The Arabic Roots of Jazz and Blues ......Gunnar Lindgren........................................................... Black Africans of Arabic culture Long before the beginning of what we call black slavery, black Africans arrived in North America. There were black Africans among Columbus ’s crew on his first journey to the New World in 1492.Even the more militant of the earliest Spanish and Portuguese conquerors, such as Cortes and Pizarro, had black people by their side. In some cases, even the colonialist leaders themselves were black, Estebanico for example, who conducted an expedition to what is now Mexico, and Juan Valiente, who led the Spaniards when they conquered Chile. There were black colonialists among the first Spanish settlers in Hispaniola (today Haiti/Dominican Republic). Between 1502 and 1518, hundreds of blacks migrated to the New World, to work in the mines and for other reasons. It is interesting to note that not all of the black colonists of the first wave were bearers of African culture, but rather of Arabic culture. They were born and raised on the Iberian Peninsula (today Spain, Portugal, and Gibraltar) and had, over the course of generations, exchanged their original African culture for the Moorish (Arabic)culture. Spain had been under Arabic rule since the 8th century, and when the last stronghold of the Moors fell in 1492,the rulers of the reunified Spain – King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella – gave the go-ahead for the epoch-making voyages of Columbus. Long before, the Arabs had kept and traded Negro slaves. We can see them in old paintings, depicted in various settings of medieval European society. -

Arabic Music. It Began Something Like This : "The Arabs Are Very

ARAP.IC MUSIC \\y I. AURA WILLIAMS man's consideratinn of Ininian affairs, his chief cinestions are, IN^ "\Miat of the frture?" and "What of the past?" History helps him to answer lioth. Dissatisfied with history the searching mind asks again, "And Ijcfore that, what?" The records of the careful digging of archeologists reveal, that many of the customs and hahits of the ancients are not so different in their essence from ours of today. We know that in man's rise from complete savagery, in his first fumblings toward civilization there was an impulse toward beauty and toward an expression of it. We know too, that his earliest expression was to dance to his own instinctive rhythms. I ater he sang. Still later he made instruments to accompany his dancing and his singing. At first he made pictures of his dancing and his instruments. Later he wrote about the danc- ing and his instruments. Later he wrote about the dancing and sing- ing and the music. Men have uncovered many of his pictures and his writings. From the pictures we can see what the instruments were like. We can, perhaps, reconstruct them or similar ones and hear the (luality of sound which they supplied. But no deciphering of the writings has yet disclosed to rs what combinations or sequences of sounds were used, nor what accents marked his rhythms. While one man is digging in the earth to turn up what records he may find of man's life "before that," another is studying those races who today are living in similar primitive circumstances. -

Arabic Language and Literature 1979 - 2018

ARABIC LANGUAGEAND LITERATURE ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 1979 - 2018 ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE A Fleeting Glimpse In the name of Allah and praise be unto Him Peace and blessings be upon His Messenger May Allah have mercy on King Faisal He bequeathed a rich humane legacy A great global endeavor An everlasting development enterprise An enlightened guidance He believed that the Ummah advances with knowledge And blossoms by celebrating scholars By appreciating the efforts of achievers In the fields of science and humanities After his passing -May Allah have mercy on his soul- His sons sensed the grand mission They took it upon themselves to embrace the task 6 They established the King Faisal Foundation To serve science and humanity Prince Abdullah Al-Faisal announced The idea of King Faisal Prize They believed in the idea Blessed the move Work started off, serving Islam and Arabic Followed by science and medicine to serve humanity Decades of effort and achievement Getting close to miracles With devotion and dedicated The Prize has been awarded To hundreds of scholars From different parts of the world The Prize has highlighted their works Recognized their achievements Never looking at race or color Nationality or religion This year, here we are Celebrating the Prize›s fortieth anniversary The year of maturity and fulfillment Of an enterprise that has lived on for years Serving humanity, Islam, and Muslims May Allah have mercy on the soul of the leader Al-Faisal The peerless eternal inspirer May Allah save Salman the eminent leader Preserve home of Islam, beacon of guidance. -

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report

Arab Republic of Egypt Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities European Investment Bank L’Agence Française de Développement (AFD) Construction Authority for Potable Water & Wastewater CAPW Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report Date of issue: May 2020 Consulting Engineering Office Prof. Dr.Moustafa Ashmawy Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project NTS ESIA Report Non - Technical Summary 1- Introduction In Egypt, the gap between water and sanitation coverage has grown, with access to drinking water reaching 96.6% based on CENSUS 2006 for Egypt overall (99.5% in Greater Cairo and 92.9% in rural areas) and access to sanitation reaching 50.5% (94.7% in Greater Cairo and 24.3% in rural areas) according to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). The main objective of the Project is to contribute to the improvement of the country's wastewater treatment services in one of the major treatment plants in Cairo that has already exceeded its design capacity and to improve the sanitation service level in South of Cairo at Helwan area. The Project for the ‘Expansion and Upgrade of the Arab Abo Sa’ed (Helwan) Wastewater Treatment Plant’ in South Cairo will be implemented in line with the objective of the Egyptian Government to improve the sanitation conditions of Southern Cairo, de-pollute the Al Saff Irrigation Canal and improve the water quality in the canal to suit the agriculture purposes. This project has been identified as a top priority by the Government of Egypt (GoE). The Project will promote efficient and sustainable wastewater treatment in South Cairo and expand the reclaimed agriculture lands by upgrading Helwan Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) from secondary treatment of 550,000 m3/day to advanced treatment as well as expanding the total capacity of the plant to 800,000 m3/day (additional capacity of 250,000 m3/day). -

After the Accords Anwar Sadat

WMHSMUN XXXIV After the Accords: Anwar Sadat’s Cabinet Background Guide “Unprecedented committees. Unparalleled debate. Unmatched fun.” Letters From the Directors Dear Delegates, Welcome to WMHSMUN XXXIV! My name is Hank Hermens and I am excited to be the in-room Director for Anwar Sadat’s Cabinet. I’m a junior at the College double majoring in International Relations and History. I have done model UN since my sophomore year of high school, and since then I have become increasingly involved. I compete as part of W&M’s travel team, staff our conferences, and have served as the Director of Media for our college level conference, &MUN. Right now, I’m a member of our Conference Team, planning travel and training delegates. Outside of MUN, I play trumpet in the Wind Ensemble, do research with AidData and for a professor, looking at the influence of Islamic institutions on electoral outcomes in Tunisia. In my admittedly limited free time, I enjoy reading, running, and hanging out with my friends around campus. As members of Anwar Sadat’s cabinet, you’ll have to deal with the fallout of Egypt’s recent peace with Israel, in Egypt, the greater Middle East and North Africa, and the world. You’ll also meet economic challenges, rising national political tensions, and more. Some of the problems you come up against will be easily solved, with only short-term solutions necessary. Others will require complex, long term solutions, or risk the possibility of further crises arising. No matter what, we will favor creative, outside-the-box ideas as well as collaboration and diplomacy. -

Arte, Ciudad, Sociedad Improving

MÁSTER EN DISEÑO URBANO: ARTE, CIUDAD, SOCIEDAD IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN Tutor Dr. A. Remesar Author Sama AlMalik 1 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN 2 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN MÁSTER EN DISEÑO URBANO: ARTE, CIUDAD, SOCIEDAD IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN Tutor Dr. Antoni Remesar Author Sama AlMalik NUIB 15847882 Academic Year 2016-2017 Submitted in the support of the degree of Masters in Urban Design 3 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN 4 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN RESUMEN Las calles, barrios y ciudades de Arabia Saudita se encuentran en un estado de construcción permanente desde hace varias décadas, incentivando a la población de a adaptarse al cambio y la transformación, a estar abiertos a cambios constantes, a anticipar la magnitud de desarrollos futuros y a anhelar que el futuro se convierta en presente. El futuro, como se describe en la Visión 2030 del Príncipe Heredero Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud, promete tres objetivos principales: una economía próspera, una sociedad vibrante y una nación ambiciosa. Afortunadamente, para la capital, Riad, varios proyectos se están acercando a su finalización, haciendo cambios significativos en las calles, imagen y perfil de la ciudad. Esto configura cómo los ciudadanos interactúan con toda la ciudad, cómo se integran y reconocen nuevas calles, edificios y distritos. -

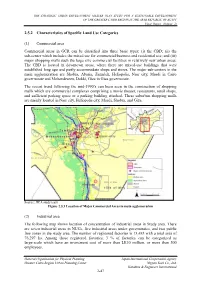

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

Download Date 01/10/2021 20:02:43

Why has the Arab League failed as a regional security organisation? An analysis of the Arab League¿s conditions of emergence, characteristics and the internal and external challenges that defined and redefined its regional security role. Item Type Thesis Authors Abusidu-Al-Ghoul, Fady Y. Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 01/10/2021 20:02:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/6333 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. WHY HAS THE ARAB LEAGUE FAILED AS A REGIONAL SECURITY ORGANISATION? An analysis of the Arab League’s conditions of emergence, characteristics and the internal and external challenges that defined and redefined its regional security role Fady Y. ABUSIDUALGHOUL submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Peace Studies School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 Fady Y. ABUSIDUALGHOUL Title: Why has the Arab League failed as a Regional Security Organisation? Keywords: Arab League, Regional Security, Regional Organisations, Middle East security, Arab Relations, Middle East conflicts ABSTRACT This study presents a detailed examination of the Arab League’s history, development, structure and roles in an effort to understand the cause of its failure as a regional security organisation. -

Morocco Hides Its Secrets Well; Who Can Riad in Marrakesh, Morocco

INTERIORS TexT KALPANA SUNDER A patio with a pool at the centre of a Morocco hides its secrets well; who can riad in Marrakesh, Morocco. A riad imagine the splendour of a riad? Slip away is known for the lush greenery that from the hustle and bustle of aggressive is intrinsic to its open-air courtyard, street vendors and step into a cocoon of making it an oasis of peace. tranquillity. Frank Waldecker/Look/Dinodia Frank 74•JetWings•December 2014 JetWings•December 2014•75 Interiors AM IN THE lovely rose-pink Moroccan Above: View from the of terracotta roofs and legions of satellite dishes. town of Marrakesh, on the fringes of the rooftop of a riad that The minaret of the Koutoubia Mosque, the tallest lets you see all the Sahara, and in true Moroccan spirit, I’m way to the medina building in the city, is silhouetted against a crimson staying at a riad. Riads are traditional (the old walled part) sky; in the distance, the evocative sound of the Moroccan homes with a central courtyard of Marrakesh. muezzin called the faithful to prayer. With arched garden; in fact, the word riad is derived Below: A traditional cloisters, pots of lush tangerine bougainvillea and fountain in the inner from the Arabic word for garden. They offer courtyard of a riad in tiled courtyards, this is indeed a visual feast. refuge from the clamour and sensory overload of Fez, Morocco’s third the streets, as well as protection from the intense largest city, brings WHAT LIES WITHIN a sense of coolness cold of the winter and fiery warmth of the summer. -

The American Mosque Report

The American Mosque 2020: Growing and Evolving Report 1 of the US Mosque Survey 2020: Basic Characteristics of the American Mosque Dr. Ihsan Bagby Research Team Dr. Ihsan Bagby, Primary Investigator and Report Table of Contents Author Research Advisory Committee Dr. Ihsan Bagby, Associate Professor of Islamic Introduction ......................................................... 3 Studies, University of Kentucky Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research, ISPU Major Findings ..................................................... 4 Dr. Besheer Mohamed, Senior Researcher, Pew Research Center Dr. Scott Thumma, Professor of Sociology of Mosque Essential Statistics ................................ 7 Religion, Hartford Seminary Number of Mosques .............................................. 7 Dr. Shariq Siddiqui, Director, Muslim Philanthropy Initiative, Indiana University Location of Mosques ............................................. 8 Riad Ali, President and Founder, American Muslim Mosque Buildings .................................................. 9 Research and Data Center Dr. Zahid Bukhari, Director, ICNA Council for Social Year Mosque Moved to Its Present Location ........ 10 Justice City/Neighborhood Resistance to Mosque Development ....................................... 10 ISPU Publication Staff Mosque Concern for Security .............................. 11 Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research Erum Ikramullah, Research Project Manager Mosque Participants ......................................... 12 Katherine Coplen, Director of Communications