The American Mosque Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

Arte, Ciudad, Sociedad Improving

MÁSTER EN DISEÑO URBANO: ARTE, CIUDAD, SOCIEDAD IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN Tutor Dr. A. Remesar Author Sama AlMalik 1 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN 2 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN MÁSTER EN DISEÑO URBANO: ARTE, CIUDAD, SOCIEDAD IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN Tutor Dr. Antoni Remesar Author Sama AlMalik NUIB 15847882 Academic Year 2016-2017 Submitted in the support of the degree of Masters in Urban Design 3 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN 4 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN RESUMEN Las calles, barrios y ciudades de Arabia Saudita se encuentran en un estado de construcción permanente desde hace varias décadas, incentivando a la población de a adaptarse al cambio y la transformación, a estar abiertos a cambios constantes, a anticipar la magnitud de desarrollos futuros y a anhelar que el futuro se convierta en presente. El futuro, como se describe en la Visión 2030 del Príncipe Heredero Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud, promete tres objetivos principales: una economía próspera, una sociedad vibrante y una nación ambiciosa. Afortunadamente, para la capital, Riad, varios proyectos se están acercando a su finalización, haciendo cambios significativos en las calles, imagen y perfil de la ciudad. Esto configura cómo los ciudadanos interactúan con toda la ciudad, cómo se integran y reconocen nuevas calles, edificios y distritos. -

Morocco Hides Its Secrets Well; Who Can Riad in Marrakesh, Morocco

INTERIORS TexT KALPANA SUNDER A patio with a pool at the centre of a Morocco hides its secrets well; who can riad in Marrakesh, Morocco. A riad imagine the splendour of a riad? Slip away is known for the lush greenery that from the hustle and bustle of aggressive is intrinsic to its open-air courtyard, street vendors and step into a cocoon of making it an oasis of peace. tranquillity. Frank Waldecker/Look/Dinodia Frank 74•JetWings•December 2014 JetWings•December 2014•75 Interiors AM IN THE lovely rose-pink Moroccan Above: View from the of terracotta roofs and legions of satellite dishes. town of Marrakesh, on the fringes of the rooftop of a riad that The minaret of the Koutoubia Mosque, the tallest lets you see all the Sahara, and in true Moroccan spirit, I’m way to the medina building in the city, is silhouetted against a crimson staying at a riad. Riads are traditional (the old walled part) sky; in the distance, the evocative sound of the Moroccan homes with a central courtyard of Marrakesh. muezzin called the faithful to prayer. With arched garden; in fact, the word riad is derived Below: A traditional cloisters, pots of lush tangerine bougainvillea and fountain in the inner from the Arabic word for garden. They offer courtyard of a riad in tiled courtyards, this is indeed a visual feast. refuge from the clamour and sensory overload of Fez, Morocco’s third the streets, as well as protection from the intense largest city, brings WHAT LIES WITHIN a sense of coolness cold of the winter and fiery warmth of the summer. -

JICNY: Morocco Jewish Tour Sunday February 16-Monday February 24, 2020

JICNY: Morocco Jewish Tour Sunday February 16-Monday February 24, 2020 Elaine Finkelstein 203-921-7133 Feb 16 - Sunday: Arrive in Casablanca - Transfer to Fez Welcome to the Casablanca airport, we hope you had a pleasant flight. Here you will be greeted by a Zayan Travel tour manager, who will welcome you to the city of the French colonial legacy History awaits your arrival at the Museum of the Jews. Birthed in the Jewish Community of Casablanca in 1997, the Museum of Moroccan Judaism of Casablanca will not only provide you with a blast from the past but you will also experience ethnography in its finest form. It is an amazing site that withstood the test of time – truly a historic marvel! A well put orientation accompanied by an amazing visit to the Hassan II mosque awaits you. Direct transfer to Fez with a detour to Meknes Accommodation: Riad Myra - Fez Feb 17 - Monday: Fez Guided City Tour Third times the charm, have a hearty breakfast as you wake up fresh and rejuvenated after a good night’s rest. You will now be unraveling the mysteries of Fez while feasting your eyes on the Moorish style and European art décor. Here you will be gazing at the stunning panoramic views of Medina of Fez from Borj Sud, and then you will be heading towards the majestic Fez Medina (Old City). Fill your day with enchanting sights of the classic venues of the Old City, encompassing everything from baffling alleys to crowded markets and a lot more! • The Medersa Bou Inania • Bab Boujloud (blue gate) • The Splendid fountain at Place Nejjarine • Visit Jewish Fez - the Mellah (Jewish Quarter) the ancient Jewish graveyard and the synagogue that is today protectively guarded by its Muslim caretaker • Visit the Souks Markets - where the skillful weavers, carpet makers, copper beaters, and snail sellers practice their trade as they did a thousand years ago • The Chaouwara tanneries • Local leather and pottery factories Accommodation: Riad Myra - Fez Feb 18 – Tuesday: Fez – Day Trip to Chefchaouen | Fez We will pick you up from your riad earlier. -

New AFED Properties on the Horizon

Vol 39, No. 1 Rabi Al-Thani 1442, A.H. December, 2020 AFED Business Park Dar es Salaam Amira Apartments Dar es Salaam New AFED Properties Zahra Residency Madagascar on the Horizon Federation News • Conferences: Africa Federation, World Federation, Conseil Regional Des Khojas Shia Ithna-Asheri Jamates De L’ocean Indien. • Health: Understanding the Covid-19 Pandemic. • Opinion: Columns from Writers around the World • Qur’an Competition Az Zahra Bilal Centre Tanga • Jamaat Elections Jangid Plaza epitomizes the style and status of business in the Floor for Shopping Center most prestigious location in Dar Es Salaam with its elegant High Speed Internet access capability design and prominent position to the Oysterbay Area. Businesses gain maximum exposure through its strategic location Fully Controllable Air Conditioning in Each Floor on Ally Hassan Mwinyi Road and its close proximity to the CCTV cameras and access control, monitored from central commercial hub of Dar Es Salaam a prime location for security room world-class companies and brands. 24 Hour Security Amenities: Location: Main Road Ally Hassan Mwinyi Road and Junction of BOOK YOUR SPACE NOW Protea Apartment (Little Theater) Contact us at: Jangid Plaza Ltd. Retail outlets on the ground and mezzanine floor P.O.Box 22028, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. 2 Eight Floors of A-Class office Space, Offices ranging fom 109m Sales Hotline: +255 784 737-705, +255 786 286-200 2 to Over 1800m Email: shafi[email protected] Website: www.jangidplaza.co.tz Features: Electronic access cards for secured parking and tenants areas Drop off Area at Building Entrance Designated visitors parking 120 Covered Parking Spaces on Basement Levels Luxurious Interior Design of Ground Floor Lobby Using Marble and Granite Four (4) High Speed Lifts and Two (2) Escalators on Ground Floor for Shopping Center 3. -

From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’S Popular Mobilisation Units

From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units By Inna Rudolf CONTACT DETAILS For questions, queries and additional copies of this report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS United Kingdom T. +44 20 7848 2098 E. [email protected] Twitter: @icsr_centre Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. © ICSR 2018 From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units Contents List of Key Terms and Actors 2 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 – The Birth and Institutionalisation of the PMU 11 Chapter 2 – Organisational Structure and Leading Formations of Key PMU Affiliates 15 The Usual Suspects 17 Badr and its Multi-vector Policy 17 The Taming of the “Special Groups” 18 Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq – Righteousness with Benefits? 18 Kata’ib Hezbollah and the Iranian Connection 19 Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada – Seeking Martyrdom in Syria? 20 Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba – a Hezbollah Wannabe? 21 Saraya al-Khorasani – Tehran’s Satellite in Iraq? 22 Kata’ib Tayyar al-Risali – Iraqi Loyalists with Sadrist Roots 23 Saraya al-Salam – How Rebellious are the Peace Brigades? 24 Hashd al-Marji‘i – the ‘Holy’ Mobilisation 24 Chapter 3 – Election Manoeuvring 27 Betting on the Hashd 29 Chapter 4 – Conclusion 33 1 From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units List of Key Terms and Actors AAH: -

Colours of Morocco $

17 DAY CULTURAL ODYSSEY COLOURS OF MOROCCO $ PER PERSON 3999 TWIN SHARE TYPICALLY $7199 MARRAKECH • FEZ • ESSAOUIRA • CASABLANCA THE OFFER 17 DAY COLOURS OF MOROCCO A feast for the eyes; food for the soul. Morocco is a destination that ticks all the boxes and then some. From the desert kasbah of Aït Ben Haddou to the $3999 mosques of Casablanca, the sand dunes of Erg Chebbi to the colourful souks of Marrakech, every step reveals another wondrous sight. Experience the rich history and unique natural beauty of Morocco on this 17 day highlights tour visiting Fez, Casablanca, Essaouira, Marrakech, and beyond. Explore the vibrant cities of Rabat and Fez; visit the famous desert kasbah of Ait Ben Haddou; feel dwarfed by Todgha Gorge in the Atlas Mountains; explore the Roman ruins of Volubilis; journey through the stunning Dadès Valley; travel to the real life oasis of Tinghir; enjoy a sunset camel ride through the Erg Chebbi sand dunes; and so much more! This incredible package includes return international flights, 14 nights riad and desert kasbah accommodation, English-speaking tour guide and more. *Please note: all information provided in this brochure is subject to both change and availability. Prior to purchase please check the current live deal at www.tripadeal.com.au or contact our customer service team on 1300 00 TRIP (8747) for the most up-to-date information. If you have already purchased this deal, the terms and conditions on your Purchase Confirmation apply and take precedence over the information in this brochure. BUY ONLINE: www.tripadeal.com.au CALL: 135 777 Offer available for a limited time or until sold out. -

Tour Highlights.ICAA Morocco.2014.Eblast

ICAA Private Morocco: Casablanca and the Imperial Cities Exemplary Sites, Private Residences & Gardens of Rabat, Casablanca, Fes, Meknes & Marrakech Sponsored by Institute of Classical Architecture & Art Arranged by Pamela Huntington Darling, Exclusive Cultural Travel Programs Saturday, May 10th to Sunday, May 18th, 2014: 8 days & 8 nights The Kingdom of Morocco's rich and ancient culture bears the traces of conquerors, invaders, traders, nomads and colonists—from the Phoenicians and Romans to the Spanish and French. An extravagant mosaic of stunning landscapes, richly textured cities and welcoming people, Morocco's high mountain ranges, lush forests, sun-baked desserts and exotic cities, including many UNESCO World Heritage sites, make for a traveler's paradise. Gateway to Africa, the influence of the many peoples and cultures that have left their mark on this storied country is captured in the architecture and monuments, gardens, art, music and cuisine. The bustling bazaars and splendid Medinas, Kasbahs and mosques of Casablanca and the Imperial Cities offer travelers a tantalizing mix of ancient and modern. For eight magical days, in the company of our expert lecturer, we will explore some of Morocco's most important sites and monuments under privileged conditions and received by officials and prominent members of the community. We will enjoy rare and unique visits, receptions and dinners with the owners of superb private riads (palaces), and villas celebrated for their architecture, gardens, interior décor and world-class art collections, details of which will be sent to confirming participants. Tour Highlights Extra Day: Friday, May 9th: Rabat We recommend that you arrive in Casablanca one day prior to the official program. -

DFIF::FÊJ JC<<G@E> 9<8LKP

OPOPOPOPOPOPOP=<Q =<Q DFIF::FÊJ JC<<G@E> 9<8LKP KlZb\[XnXp`ek_\efik_f] DfifZZf#=\q_XjÓ\iZ\cp gifk\Zk\[`kjcfe^$jkXe[`e^ kiX[`k`fejXe[i`Z_Zlckli\ WORDS TAHIR SHAH | PHOTOGRAPHS JULIAN LOVE One of the many ornamental doorways inside the dilapidated Glaoui Palace. Opposite: a man sits and reads in the Medersa Bou Inania, one of Fez’s finest XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX theological colleges 82 November 2009 =yJ =<Q É=<Q@JN@K?FLK;FL9KK?<>I<8K<JKD<;@<M8C 8I89:@KPJK@CC@EK8:K8EPN?<I<FE<8IK?Ê Above: Abdou, the guardian of Glaoui Palace, has lived there for as long as he can remember. The palace, like Fez, is so full of atmosphere and mystery that it doesn’t take much effort to imagine yourself back in a land of storytellers and treasures. Opposite left: richly scented, brightly coloured spices line the Talaa Kebira, one of the city’s main streets. Opposite right: turn a corner and you might stumble on such a traditional riad doorway decorated by skilled craftsmen. Opposite bottom: banisters, columns and ceilings have been painstakingly adorned with mosaics and hand-painted motifs in the harem of the Glaoui Palace ying behind a steel door on a lived at the Glaoui for as long as he can cheek, evaporating before reaching his dusty lane in Fez stands one of recall. If you ask him whether he was born chin. The afternoon is swelteringly hot the most unexpected treasures there, or if he actually owns the palace, he – the high 30s. The geese and ducks in the of North Africa – Glaoui Palace. -

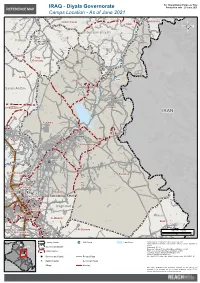

IRAQ - Diyala Governorate Production Date : 28 June 2021 REFERENCE MAP Camps Location - As of June 2021

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ - Diyala Governorate Production date : 28 June 2021 REFERENCE MAP Camps Location - As of June 2021 # # # # # # # # # # # # P! # # Qaryat Khashoga AsriyaAsriya al-Sutayihal-Sutayih # Big UboorUboor## #QalqanluQalqanlu BigBig Bayk Zadah Tilakoi PaykuliPaykuli# # # Kawta Sarkat BoyinBoyin Qaryat Khashoga# Big #Bayk Zadah Tilakoi GulaniGulani HamaHama # Zmnako Psht Qala Kawta Sarkat Samakah Village GarmiyanGarmiyan MalaMala OmarOmar MasoyMasoy BargachBargach BarkalBarkal CampeCampe Zmnako Psht Qala # Satayih Upper Hay Ashti Samakah Village QalqanluQalqanlu # # QalanderQalander# # MahmudMahmud # # Satayih Upper Hay Ashti TalTal RabeiaRabeia CollectiveCollective MasuiMasui HamaHama TilakoyTilakoy Pskan Khwarw SarshatSarshat UpperUpper TawanabalTawanabalGrdanaweGrdanawe # # # LittleLittle KoyikKoyik ChiyaChiya Pskan Khwarw # # # # AlwaAlwa PashaPasha TownTown # # #FarajFaraj #QalandarQalandar # MordinMordin FakhralFakhral # JamJam BoorBoor Charmic ZarenZaren # # Charmic # Satayih KurdamiriKurdamiri # NejalaNejala Satayih ShorawaShorawa ChalawChalaw DewanaDewana AzizAziz BagBag HasanHasan ParchunParchun FaqeFaqe MustafaMustafa # # Yousifiya # # # # # HamaiHamai Halabcha Hasan Shlal Yousifiya KaniKani ZhnanZhnan Hasan Shlal # AlbuAlbu MuhamadMuhamad Chamchamal RamazanRamazan MamkaMamka SulaimanSulaiman GorGor AspAsp # # # # KurdamirKurdamir # # AhmadAhmad ShalalShalal ZaglawaZaglawa Aghaja Mashad Ahmad OmarOmar AghaAgha # # Aghaja Mashad Ahmad TazadeTazade ImamImam Quli Matkan# (Aroba(Aroba TheThe DijlaDijla -

The Rise of Islam As a Constitutive Revolution

Chapter 5 Revolution in Early Islam: The Rise of Islam as a Constitutive Revolution SAÏD AMIR ARJOMAND We conceive of revolution in terms of its great social and political consequences. In a forthcoming comparative and historical study of revolutions, I contrast to the state-centered revolutions of modern times with another ideal-type of revolution which I call the ‘integrative’ revolution (see the Appendix). This ideal type of revolution – which is an aspect of all revolutions – expresses two simple ideas: revolutions 1) bring to power a previously excluded revolutionary elite, and 2) enlarge the social basis of the political regime. This makes integrative revolu- tions not just political but also ‘social revolutions.’ Integrative revolution is in turn divided into three subtypes, the two sub-types I derive from Aristotle-Pareto and Ibn Khaldun are so labeled. The ‘constitutive’ type is my own invention, of- fering the sharpest contrast to the state-centered or ‘Tocquevillian’ type in that it is the typical pattern of radical change in the political order through the enlarge- ment of political community in ‘stateless societies,’ be they of 6th century BCE Greece or 7th century CE Arabia. In addition to this structural typology, we need to come to terms with the mo- tives and goals of the revolutionaries as historical actors, and here I do what may be politically incorrect from the viewpoint of the theory community by using the term teleology, not in the strict Aristotelian sense but rather as a term denoting the directionality of revolution. Through teleology, I seek to capture the distinc- tive direction of a revolution, its intended or intentionally prefigured conse- quences. -

Identity and Its Reflection on the Design and Forming in Islamic Design Assoc

مجلة العمارة والفنون العدد السادس عشر Identity and its reflection on the design and forming in Islamic design Assoc. Prof. Dr. Dalia Sami Thabet Georgy Associate Professor in Interior Design and furniture - Faculty of Applied arts [email protected] [email protected] Abstract One philosopher saw that values can only be understood in terms of what people feel. Even the creative process is linked to man, society, age and its roots in history and the reason for our interest in history stems from our understanding of art on the basis that the contemporary artist does not start from emptiness; it is a broad and fertile human accumulation For thousands of years through the attempts of many people and continue to understand the world. This understanding is often the result of the interaction between the individual and social dimensions of heritage and contemporary, based on the history that cannot be ignored in the creative process and the recognition of art in the greatest achievements of great artists including the attraction and genius of history and the subject does not stop at this point but should Taking into account contemporary trends to deal with designs to achieve sustainability and preservation of natural conditions and the environment and urban areas, which creates special features interact with tourists as a result affects the mental image surrounding some of the tourist areas to become one of the factors Attractions in these areas so that any country can obtain a competitive advantage through the development of designs