Maley-Hazaras-4.3.20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Mosque Report

The American Mosque 2020: Growing and Evolving Report 1 of the US Mosque Survey 2020: Basic Characteristics of the American Mosque Dr. Ihsan Bagby Research Team Dr. Ihsan Bagby, Primary Investigator and Report Table of Contents Author Research Advisory Committee Dr. Ihsan Bagby, Associate Professor of Islamic Introduction ......................................................... 3 Studies, University of Kentucky Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research, ISPU Major Findings ..................................................... 4 Dr. Besheer Mohamed, Senior Researcher, Pew Research Center Dr. Scott Thumma, Professor of Sociology of Mosque Essential Statistics ................................ 7 Religion, Hartford Seminary Number of Mosques .............................................. 7 Dr. Shariq Siddiqui, Director, Muslim Philanthropy Initiative, Indiana University Location of Mosques ............................................. 8 Riad Ali, President and Founder, American Muslim Mosque Buildings .................................................. 9 Research and Data Center Dr. Zahid Bukhari, Director, ICNA Council for Social Year Mosque Moved to Its Present Location ........ 10 Justice City/Neighborhood Resistance to Mosque Development ....................................... 10 ISPU Publication Staff Mosque Concern for Security .............................. 11 Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research Erum Ikramullah, Research Project Manager Mosque Participants ......................................... 12 Katherine Coplen, Director of Communications -

New AFED Properties on the Horizon

Vol 39, No. 1 Rabi Al-Thani 1442, A.H. December, 2020 AFED Business Park Dar es Salaam Amira Apartments Dar es Salaam New AFED Properties Zahra Residency Madagascar on the Horizon Federation News • Conferences: Africa Federation, World Federation, Conseil Regional Des Khojas Shia Ithna-Asheri Jamates De L’ocean Indien. • Health: Understanding the Covid-19 Pandemic. • Opinion: Columns from Writers around the World • Qur’an Competition Az Zahra Bilal Centre Tanga • Jamaat Elections Jangid Plaza epitomizes the style and status of business in the Floor for Shopping Center most prestigious location in Dar Es Salaam with its elegant High Speed Internet access capability design and prominent position to the Oysterbay Area. Businesses gain maximum exposure through its strategic location Fully Controllable Air Conditioning in Each Floor on Ally Hassan Mwinyi Road and its close proximity to the CCTV cameras and access control, monitored from central commercial hub of Dar Es Salaam a prime location for security room world-class companies and brands. 24 Hour Security Amenities: Location: Main Road Ally Hassan Mwinyi Road and Junction of BOOK YOUR SPACE NOW Protea Apartment (Little Theater) Contact us at: Jangid Plaza Ltd. Retail outlets on the ground and mezzanine floor P.O.Box 22028, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. 2 Eight Floors of A-Class office Space, Offices ranging fom 109m Sales Hotline: +255 784 737-705, +255 786 286-200 2 to Over 1800m Email: shafi[email protected] Website: www.jangidplaza.co.tz Features: Electronic access cards for secured parking and tenants areas Drop off Area at Building Entrance Designated visitors parking 120 Covered Parking Spaces on Basement Levels Luxurious Interior Design of Ground Floor Lobby Using Marble and Granite Four (4) High Speed Lifts and Two (2) Escalators on Ground Floor for Shopping Center 3. -

Weekly Risk Roundup

Hurricane texas Weekly Risk Roundup HEADLINES FROM THIS WEEK • Potential Terror Incident in France – A gunman claiming allegiance to the Islamic State group fired shots and took hostages at a supermarket in the town of Trebes in France on 23 March. Police were also dealing with a shooting in nearby Carcassonne. Estimates suggest that there are three dead and two injured in these two incidents, not including the gunman who is believed to have been killed as police stormed the supermarket. • Peru President Offers Resignation – The president of Peru offered his resignation on 21 March 2018, ahead of an impeachment vote regarding corruption charges. This could see power passed to First Vice President Martin Vizcarra. President Kuczynski has criticised opponents led by one-time presidential nominee and daughter of former strongman leader Alberto Fujimori, Keiko Fujimori. There is a potential for a new election to be called within a year. Protests have occurred in Lima and reports suggest they have turned violent. • Kabul Bombing – At least 32 people were killed after a suicide bombing at the Sakhi Shrine in Kabul, Afghanistan. The attack came as crowds gathered to celebrate Nowruz festival or Persian New Year; many in the crowd belonged to the Shia minority. The attack was claimed by the Islamic State branch in Afghanistan. • Austin Bomber Killed – The individual believed to have been behind five bombings in the American city of Austin which killed two people, was killed on 21 March. He also stands accused of injuring six others. The culprit was killed when he detonated a bomb after a police chase; his motive remains unclear at this time. -

From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’S Popular Mobilisation Units

From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units By Inna Rudolf CONTACT DETAILS For questions, queries and additional copies of this report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS United Kingdom T. +44 20 7848 2098 E. [email protected] Twitter: @icsr_centre Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. © ICSR 2018 From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units Contents List of Key Terms and Actors 2 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 – The Birth and Institutionalisation of the PMU 11 Chapter 2 – Organisational Structure and Leading Formations of Key PMU Affiliates 15 The Usual Suspects 17 Badr and its Multi-vector Policy 17 The Taming of the “Special Groups” 18 Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq – Righteousness with Benefits? 18 Kata’ib Hezbollah and the Iranian Connection 19 Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada – Seeking Martyrdom in Syria? 20 Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba – a Hezbollah Wannabe? 21 Saraya al-Khorasani – Tehran’s Satellite in Iraq? 22 Kata’ib Tayyar al-Risali – Iraqi Loyalists with Sadrist Roots 23 Saraya al-Salam – How Rebellious are the Peace Brigades? 24 Hashd al-Marji‘i – the ‘Holy’ Mobilisation 24 Chapter 3 – Election Manoeuvring 27 Betting on the Hashd 29 Chapter 4 – Conclusion 33 1 From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units List of Key Terms and Actors AAH: -

Tfslit 4 I'llff'i::!;Ks

i vol. xii, m. 1. SUNDAY, MARCH 22, 1981 (IIAMAL 2, 1360, U.S.) PRICE AFS. 'Red tulip' festival opens Karmal greets Bani Sadr on ': ' with prayers for progress Nowroze KABUL, March 22 (Ba- MAZARE SHARIF, Mar- firing of guns,amids the lies in the beginning of the 4 ''': khtar) Babrak Karmal, I ch 22 (Bakhtar). The clappings of thousands of 1360 dacade of the curr- tfSlit :!;kS: General Secretary of the ndard of the holy shrine of pious Moslems, who Had ent century, but also espe- PDPA CC, President of the fourth caliph of Islam, rallied from all parts cially it will i'llff'Li RC DRA here in the fact that the and Prime Hazrate Shahe Wolayat-maa- b of the country. be an auspicious year with Minister, has sent a cong- Ali Karamullah Waj-ha- , striking victories, which we ratulatory telegram to His was raised amid scen- After the recitation of so- will certainly achieve, and Excellency Bani Sadr, es of enthusiasm and pray-er- s me verses from the Holy also that it will witness the President of the Repub- for progress of the ho- Koran, Dipl. Eng. Ahmad third anniversary of the yo- lic of Iran on the occasion meland and further succ- Yasln Sadiqi, secretary of ung Democratic Republic of Nawroze Eid. esses of the Saur Revolu- the provincial committee of of Afghanistan". tion, with which the tradi- Balkh, in a speech greeted Anahita for tional 'red tulip festival' op- the audience on the occas- During the ceremony, at ened here yesterday. ion of the New Year. -

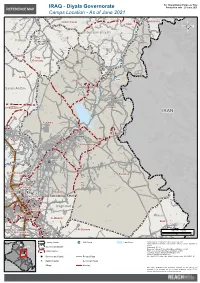

IRAQ - Diyala Governorate Production Date : 28 June 2021 REFERENCE MAP Camps Location - As of June 2021

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ - Diyala Governorate Production date : 28 June 2021 REFERENCE MAP Camps Location - As of June 2021 # # # # # # # # # # # # P! # # Qaryat Khashoga AsriyaAsriya al-Sutayihal-Sutayih # Big UboorUboor## #QalqanluQalqanlu BigBig Bayk Zadah Tilakoi PaykuliPaykuli# # # Kawta Sarkat BoyinBoyin Qaryat Khashoga# Big #Bayk Zadah Tilakoi GulaniGulani HamaHama # Zmnako Psht Qala Kawta Sarkat Samakah Village GarmiyanGarmiyan MalaMala OmarOmar MasoyMasoy BargachBargach BarkalBarkal CampeCampe Zmnako Psht Qala # Satayih Upper Hay Ashti Samakah Village QalqanluQalqanlu # # QalanderQalander# # MahmudMahmud # # Satayih Upper Hay Ashti TalTal RabeiaRabeia CollectiveCollective MasuiMasui HamaHama TilakoyTilakoy Pskan Khwarw SarshatSarshat UpperUpper TawanabalTawanabalGrdanaweGrdanawe # # # LittleLittle KoyikKoyik ChiyaChiya Pskan Khwarw # # # # AlwaAlwa PashaPasha TownTown # # #FarajFaraj #QalandarQalandar # MordinMordin FakhralFakhral # JamJam BoorBoor Charmic ZarenZaren # # Charmic # Satayih KurdamiriKurdamiri # NejalaNejala Satayih ShorawaShorawa ChalawChalaw DewanaDewana AzizAziz BagBag HasanHasan ParchunParchun FaqeFaqe MustafaMustafa # # Yousifiya # # # # # HamaiHamai Halabcha Hasan Shlal Yousifiya KaniKani ZhnanZhnan Hasan Shlal # AlbuAlbu MuhamadMuhamad Chamchamal RamazanRamazan MamkaMamka SulaimanSulaiman GorGor AspAsp # # # # KurdamirKurdamir # # AhmadAhmad ShalalShalal ZaglawaZaglawa Aghaja Mashad Ahmad OmarOmar AghaAgha # # Aghaja Mashad Ahmad TazadeTazade ImamImam Quli Matkan# (Aroba(Aroba TheThe DijlaDijla -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 ‐ ‐ ‐ NEA PSHSS 14 001 Weekly Report 47–48 — July 7, 2015 Michael D. Danti, Cheikhmous Ali, Michel Maqdisi, Tate Paulette, Allison Cuneo, Kathryn Franklin, LeeAnn Barnes Gordon, Kyra Kaercher, and Erin Van Gessel Executive Summary During the reporting period in Syria, ISIL militants in the northern town of Manbij intercepted an individual(s) transporting Palmyrene funerary sculptures removed from tombs at the archaeological site and/or from the collections of the Tadmor Museum. ISIL sentenced this individual to public lashing and deliberately destroyed the sculptures. ISIL later released a video of these acts on social media sites. Media and social media sources variously identified this individual(s) as an antiquities trafficker(s), presumably unaffiliated with ISIL’s own‐ antiquities trafficking network, or an activist(s) attempting to save the sculptures. ISIL also released a video showing the mass execution of 25 SARG military personnel in the Palmyra Roman era Theater (probably built in the late 2nd–early 3rd Century CE and partially a modern reconstruction). This execution occurred May 27, 2015 and the video was released on July 4. The use of a well known heritage site as the backdrop for this horrific act has numerous ramifications regarding ISIL’s use of heritage in propaganda and future perceptions of this heritage site and its intangible associations. DGAM Daraa MuseumIn western Syria, ASOR CHI sources have reported damage to archaeological sites caused by intense military clashes in the area of Zabadani. In southern Syria, the reports that the suffered minor damage to the interior of the building and the exterior garden courtyard during military combat. -

Hn Encyc~Opedir

HN ENCYC~OPEDIR RFGHHNISTRNIDHNGLRDESH IINDIR INEPHL IPRHISTRN ISRI LHNHR MHRGHRETn. Ml~~s. PETER J. c~nus. HNOSHRHH OIHMONO. EDITORS Routledge New York London s SACRED GEOGRAPHY to house it; the temple can therefore be located wher Sacred geography is an aspect of a people's cosmology, ever its patron desires. In folk religion, by contrast, gods part of the way they see the world as ordered and sig manifest themselves at particular spots in "self-formed" nificant. In South Asia this topic encompasses religious (svayambhii), unhewn rocks. People recognize the man valuations of nature; ideas about the earthly locations ifestation because the place is marked by a spontaneous of gods and goddesses; memories of the locations of flow of blood, by a cow lactating onto the ground, or events in the lives of saints, founders, and divine in by some other natural wonder. carnations; notions of center and periphery, and ideas In many cases, a pai1icular place of worship of a de about directional orientation; notions of replication and ity is understood to be the locus of some event in the microcosm; and ideas about the holiness of certain re deity's life-the killing of a demon, for instance, or the gions and territories. deity's wedding. When a god (or, less often, a goddess) The religious valuation of nature in South Asia is understood to have descended to earth in human form focuses on mountains, rivers, and the wilderness. las an avutiira), a number of different spots are identi Mountains and rivers are not only the abodes of deities fied as loci of specific episodes in the avatara's life story. -

Nowruz: Heralding New Year in a Unique Way in Afghanistan Farid Ahmad Farhang, Director of Govt

02 Editorial & opinion TUESDAY-MARCH 23, 2021 I n t e r n a t i o n a l D a i l y Nowruz: Heralding New Year in a WWW.thekabultimes.gov.af unique way in Afghanistan Farid Ahmad Farhang, Director of Govt. Dailies Mob: 0704008080 Editor-in-Chief: Hamidullah Arefi Mob: 0700163568, 020-230,1766 E-mail: [email protected] Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Fathulbari Akhgar Mob: 0707005865 Graphic designers: Edriss Akbary, Baktash Shaibani and Ali Ahmad Distribution: 2300337 - 0793531513 - 078245600 - 0766788447 Printed at: Azadi printing press Address: 2nd Floor, Liberty Printing Press Building 2nd Microrayon, Kabul, Afghanistan twitter,com/thekabultimes www.facebook.com/ thekabultimes Editorial Avoid shedding bloods in KABUL: Celebration of an- BPWH) in Mazar-e-Sharif has giv- Haft seen consists of garlic, Then cut it to small pieces and grind cient Nowruz festival in Afghani- en this peculiarity to this city that Vinegar, grass, sorb, Samanak, ap- it. Then infiltrate it with a clean stan has a long and rich historical its traditional, cultural ceremonies ple. Later people recite seven verses fabric. Then put it in a big pot and 1400, instead work for peace background. Every year, the Af- get universal reputation and pop- from holy Quran which start with stire for several hours to become ghan people celebrate the beauti- ularity. On the New Year’s Day, (S) and then pray all together with ready. Next day they open it. Dur- The solar year 1400 is like one of the past dozens of new springs that the Afghans ful Nowruz festival with special thousands of people gather in family members. -

The a to Z Guide to Afghanistan Assistance 2009

The A to Z Guide to Afghanistan Assistance 2009 AFGHANISTAN RESEARCH AND EVALUATION UNIT Improving Afghan Lives Through Research The A to Z Guide to Afghanistan Assistance 2009 Seventh Edition AFGHANISTAN RESEARCH AND EVALUATION UNIT Improving Afghan Lives Through Research IMPORTANT NOTE: The information presented in this Guide relies on the voluntary contributions of ministries and agencies of the Afghan government, embassies, development agencies and other organisations representing donor countries, national and international NGOs, and other institutions. While AREU undertakes with each edition of this Guide to provide the most accurate and current information possible, details evolve and change continuously. Users of this guide are encouraged to submit updates, additions, corrections and suggestions to [email protected]. © Copyright Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, January 2009. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be obtained by emailing areu@ areu.org.af or by calling +93 799 608 548. Coordinating Editor: Cynthia Lee Contacts Section: Sheela Rabani and Noorullah Elham Contributors: Ahmadullah Amarkhil, Amanullah Atel, Chris Bassett, Mia Bonarski, Colin Deschamps, Noorullah Elham, Susan Fakhri, Paula Kantor, Anna Larson, Sheela Rabani, Rebecca Roberts, Syed Mohammad Shah, -

NOWRUZ FESTIVAL Common Cultural Heritage of the ECO Region

THE QUARTERLY CULTURAL MAGAZINE OF ECO CULTURAL INSTITUTE (ECI) ECO HERITAGE ISSUE 28, VOLUME 9, NOWRUZ SPECIAL ISSUE ISSN 2008-546X NOWRUZ FESTIVAL Common Cultural Heritage of the ECO Region ISSN 2008-546X 9 772008 546002 Called whether Tartars, Turks or Afghans, we ف نی ن ت ی هن ا غا م و ی رتک و تار م ,Belong to one great garden, one great tree چم ی خ ی ن زاد م و از یک شا سار م .Born of a springtide that was glorious تمی ب س ز رنگ و و رب ما رحام ا ت .Distinction of colour is a sin for us ٔ هک ما رپورده یک نو بهاریم A Persian Poem by Sir Muhammad Iqbal( ), عﻻهم محمداقبال the most prominent poet of Pakistan from his book " "PAYAM-I-MASHRIQ" (Message from the East), English translation: M. HADI HUSSAIN Publisher ECO Cultural Institute (ECI) Supervision Sarvar Bakhti, President, THE QUARTERLY CULTURAL MAGAZINE OF ECO CULTURAL INSTITUTE (ECI) ECO Cultural Institute (ECI) ECO HERITAGE ISSUE 28, VOLUME 9, NOWRUZ SPECIAL ISSUE ISSN 2008-546X Director-in-Charge Mehdi Omraninejad Chief Editor Said Reza Huseini Senior Copy Editor Nastaran Nosratzadegan NOWRUZ FESTIVAL Common Cultural Heritage of the ECO Region Editorial Board Nazif Mohib Shahrani (Afghanistan) Mohammad Sakhi Rezaie (Afghanistan) Jahangir Selimkhanov (Rep. Azerbaijan) Mandana Tishehyar (Iran) ISSN 2008-546X 9 772008 546002 Elaheh Koulaee (Iran) Dosbol Baikonakov (Kazakhstan) Aizhan Bekkulova (Kazakhstan) Cover photo by: Afshin Shahroudi Inam ul-Haq Javeed (Pakistan) (The photo was higly commended in the Photo section of the Shaheena Ayub Bhatti (Pakistan) ECO International Visual Arts Festival 2012) Asliddin Nizami (Tajikistan) Dilshod Rahimi (Tajikistan) Hicabi Kırlangı (Turkey) Advisory Board Prof. -

Walk to Jerusalem Spring Week 5 We Had Another Great Week This Week

Walk to Jerusalem Spring Week 5 We had another great week this week. We had 53 participants and walked 1072.5 miles! The map below shows our progress through the end of week five (purple line). At the end of week four we had arrived at Zahedan, Iran, just over the border from Pakistan. On Monday, March 1, we proceeded to trek across Iran, hoping to arrive in Iraq by Sunday. I had no idea when I planned this tour last November that the Pope would be in Iraq when we arrived, nor was I certain we would reach Iraq in time to see him in person but we did! A note about Persians versus Arabs: Iranians view themselves as Persian, not Arabs. Persia at one point was one of the greatest empires of all time (see map on page 2). From this great culture we gained beautiful art seen in the masterful woven Persian carpets, melodic poetic verse, and modern algebra. It is referred to as an “ancient” empire, but, in fact, some Persian practices, such as equal rights for men and women and the abolishment of slavery, were way ahead of their time. The Persian Solar calendar is one of the world’s most accurate calendar systems. Persians come from Iran while Arabs come from the Arabia Peninsula. The fall Persia’s great dynasty to Islamic control occurred from 633-656 AD. Since that time surrounding Arab nations have forced the former power to repeatedly restructure, changing former Persia into present day Iran. But with history and culture this rich, it is to no surprise that Persians want to be distinguished from others including their Arab neighbors.