Muscle Brands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WIKINOMICS How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything

WIKINOMICS How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything EXPANDED EDITION Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams Portfolio Praise for Wikinomics “Wikinomics illuminates the truth we are seeing in markets around the globe: the more you share, the more you win. Wikinomics sheds light on the many faces of business collaboration and presents a powerful new strategy for business leaders in a world where customers, employees, and low-cost producers are seizing control.” —Brian Fetherstonhaugh, chairman and CEO, OgilvyOne Worldwide “A MapQuest–like guide to the emerging business-to-consumer relation- ship. This book should be invaluable to any manager—helping us chart our way in an increasingly digital world.” —Tony Scott, senior vice president and chief information officer, The Walt Disney Company “Knowledge creation happens in social networks where people learn and teach each other. Wikinomics shows where this phenomenon is headed when turbocharged to engage the ideas and energy of customers, suppli- ers, and producers in mass collaboration. It’s a must-read for those who want a map of where the world is headed.” —Noel Tichy, professor, University of Michigan and author of Cycle of Leadership “A deeply profound and hopeful book. Wikinomics provides compelling evidence that the emerging ‘creative commons’ can be a boon, not a threat to business. Every CEO should read this book and heed its wise counsel if they want to succeed in the emerging global economy.” —Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman, World Economic Forum “Business executives who want to be able to stay competitive in the future should read this compelling and excellently written book.” —Tiffany Olson, president and CEO, Roche Diagnostics Corporation, North America “One of the most profound shifts transforming business and society in the early twenty-first century is the rapid emergence of open, collaborative innovation models. -

The Application Usage and Risk Report an Analysis of End User Application Trends in the Enterprise

The Application Usage and Risk Report An Analysis of End User Application Trends in the Enterprise 8th Edition, December 2011 Palo Alto Networks 3300 Olcott Street Santa Clara, CA 94089 www.paloaltonetworks.com Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 Demographics ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Social Networking Use Becomes More Active ................................................................ 5 Facebook Applications Bandwidth Consumption Triples .......................................................................... 5 Twitter Bandwidth Consumption Increases 7-Fold ................................................................................... 6 Some Perspective On Bandwidth Consumption .................................................................................... 7 Managing the Risks .................................................................................................................................... 7 Browser-based Filesharing: Work vs. Entertainment .................................................... 8 Infrastructure- or Productivity-Oriented Browser-based Filesharing ..................................................... 9 Entertainment Oriented Browser-based Filesharing .............................................................................. 10 Comparing Frequency and Volume of Use -

Emerging Trends in Management, IT and Education ISBN No.: 978-87-941751-2-4

Emerging Trends in Management, IT and Education ISBN No.: 978-87-941751-2-4 Paper 3 A STUDY ON REINVENTION AND CHALLENGES OF IBM Kiran Raj K. M1 & Krishna Prasad K2 1Research Scholar College of Computer Science and Information Science, Srinivas University, Mangalore, India 2 College of Computer Science and Information Science, Srinivas University, Mangalore, India E-mail: [email protected] Abstract International Business Machine Corporation (IBM) is one of the first multinational conglomerates to emerge in the US-headquartered in Armonk, New York. IBM was established in 1911 in Endicott, New York, as Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR). In 1924, CTR was renamed IBM. Big Blue has been IBM's nickname since 19 80. IBM stared with the production of scales, punch cards, data processors and time clock now produce and sells computer hardware and software, middleware, provides hosting and consulting services.It has a worldwide presence, operating in over 175 nations with 3,50,600 staff with $79. 6 billion in annual income (Dec 2018). It is currently competing with Microsoft, Google, Apple, and Amazon. 2012 to 2017 was tough time for IBM, although it invests in the field of research where it faced challenges while trying to stay relevant in rapidly changing Tech-Market. While 2018 has been relatively better and attempting to regain its place in the IT industry. With 3,000 scientists, it invests 7% of its total revenue to Research & Development in 12 laboratories across 6 continents. This resulted in the U.S. patent leadership in IBM's 26th consecutive year. In 2018, out of the 9,100 patents that granted to IBM 1600 were related to Artificial Intelligence and 1,400 related to cyber-security. -

UNIT CONVERSION FACTORS Temperature K C 273 C 1.8(F 32

Source: FUNDAMENTALS OF MICROSYSTEMS PACKAGING UNIT CONVERSION FACTORS Temperature K ϭ ЊC ϩ 273 ЊC ϭ 1.8(ЊF Ϫ 32) ЊR ϭ ЊF ϩ 460 Length 1 m ϭ 1010 A˚ ϭ 3.28 ft ϭ 39.4 in Mass 1 kg ϭ 2.2 lbm Force 1 N ϭ 1 kg-m/s2 ϭ 0.225 lbf Pressure (stress) 1 P ϭ 1 N/m2 ϭ 1.45 ϫ 10Ϫ4 psi Energy 1 J ϭ 1W-sϭ 1 N-m ϭ 1V-C 1Jϭ 0.239 cal ϭ 6.24 ϫ 1018 eV Current 1 A ϭ 1 C/s ϭ 1V/⍀ CONSTANTS Avogadro’s Number 6.02 ϫ 1023 moleϪ1 Gas Constant, R 8.314 J/(mole-K) Boltzmann’s constant, k 8.62 ϫ 10Ϫ5 eV/K Planck’s constant, h 6.63 ϫ 10Ϫ33 J-s Speed of light in a vacuum, c 3 ϫ 108 m/s Electron charge, q 1.6 ϫ 10Ϫ18 C SI PREFIXES giga, G 109 mega, M 106 kilo, k 103 centi, c 10Ϫ2 milli, m 10Ϫ3 micro, 10Ϫ6 nano, n 10Ϫ9 Downloaded from Digital Engineering Library @ McGraw-Hill (www.digitalengineeringlibrary.com) Copyright © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved. Any use is subject to the Terms of Use as given at the website. Source: FUNDAMENTALS OF MICROSYSTEMS PACKAGING CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO MICROSYSTEMS PACKAGING Prof. Rao R. Tummala Georgia Institute of Technology ................................................................................................................. Design Environment IC Thermal Management Packaging Single Materials Chip Opto and RF Functions Discrete Passives Encapsulation IC Reliability IC Assembly Inspection PWB MEMS Board Manufacturing Assembly Test Downloaded from Digital Engineering Library @ McGraw-Hill (www.digitalengineeringlibrary.com) Copyright © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies. -

DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2

Flash 6X9 / DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2 DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration 00-FM.indd 1 9/17/13 2:26 PM Flash 6X9 / DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2 00-FM.indd 2 9/17/13 2:26 PM Flash 6X9 / DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2 DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration Paul Zikopoulos Sam Lightstone Matt Huras Aamer Sachedina George Baklarz New York Chicago San Francisco Athens London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi Singapore Sydney Toronto 00-FM.indd 3 9/17/13 2:26 PM Flash 6X9 / DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2 McGraw-Hill Education books are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative, please visit the Contact Us pages at www.mhprofessional.com. DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration: New Dynamic In-Memory Analytics for the Era of Big Data Copyright © 2014 by McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. Printed in the Unit- ed States of America. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of pub- lisher, with the exception that the program listings may be entered, stored, and exe- cuted in a computer system, but they may not be reproduced for publication. All trademarks or copyrights mentioned herein are the possession of their respective owners and McGraw-Hill Education makes no claim of ownership by the mention of products that contain these marks. -

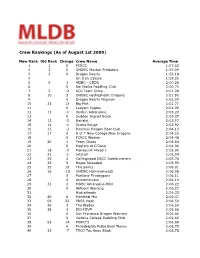

Ranking System.Xlsx

Crew Rankings (As of August 1st 2009) New Rank Old Rank Change Crew Name Average Time 1 1 0 FCRCC 1:57.62 2 2 0 OHDBC Mayfair Predators 1:59.09 3 3 0 Dragon Beasts 1:59.18 4 On S'en Calisse 1:59.25 561ADBC - CSDC 2:00.26 6 0 Kai Ikaika Paddling Club 2:00.73 7 5 -2 SCC Team Chiro 2:01.28 8 10 2 OHDBC Hydrophobic Dragons 2:01.90 9 0 Dragon Hearts Magnum 2:02.59 10 23 13 Big Fish 2:02.77 11 0 Laoyam Eagles 2:02.99 12 11 -1 Verdun Adrenaline 2:03.22 13 0 Sudden Impact Black 2:03.37 14 12 -2 Hanalei 2:03.57 15 14 -1 Scotia Rouge 2:03.92 16 13 -3 Piranhas Dragon Boat Club 2:04.13 17 17 0 U of T New College New Dragons 2:04.25 18 0 FCRCC Women 2:04.48 19 20 1 Team Chaos 2:04.84 20 0 Masters of D'Zone 2:04.96 21 19 -2 Manayunk Mixed I 2:05.00 22 21 -1 Jetstart 2:05.04 23 25 2 Collingwood DBCC Sidelaunchers 2:05.76 24 29 5 Mojos Reloaded 2:05.95 25 35 10 The Saints 2:06.01 26 16 -10 OHDBC Hammerheads 2:06.08 27 0 Portland Firedragons 2:06.11 28 0 Anniemaniacs 2:06.14 29 31 2 MDBC Adrenaline-HRV 2:06.22 30 0 Without Warning 2:06.27 31 HydraHeads 2:06.33 32 40 8 Montreal Mix 2:06.47 33 56 23 PDBC Heat 2:06.50 34 36 2 The Blades 2:06.50 35 38 3 DCH DVP 2:06.56 36 0 San Francisco Dragon Warriors 2:06.60 37 0 Victoria College Paddling Club 2:06.66 38 52 14 MOFO''s 2:06.68 39 0 Philadelphia Police Boat Teams 2:06.75 40 33 -7 TECO Tan Anou Black 2:06.78 41 41 0 3R Dragon - Mixed 2:07.19 42 37 -5 TECO Tan Anou Red 2:07.20 43 49 6 University Elite Force 2:07.27 44 39 -5 Mayfair Warriors 2:07.39 45 51 6 Hydroblades 2:07.39 46 24 -22 PDBC 2:07.79 47 0 UC -

Case Studies on Innovation

I N N O V A A T I O N 1 www.ibscdc.org ITC’s E-Choupal: A Mirage of the American studios declared in May 2007 Immelt charted his own leadership style Poor? that it had obtained the rights for and brought about a cultural revolution in developing a theme park based on the GE. Expectations were high and the E-Choupal is a novel initiative of ITC extremely successful character of the challenges were many. Immelt had to face Limited (ITC), an Indian conglomerate, popular culture Harry Potter in US, UK several challenges. He had to provide to improve its marketing channel in and all over the world. Walt Disney parks leadership and lend vision to a large, diverse agriculture. It has its roots in Project and resorts have also tried to get the rights conglomerate like GE in the post 9/11 Symphony – a pilot project launched in for Harry Potter theme park but failed to volatile global business scenario. He also 1999 to organise ITC’s agri business. The strike a deal with the creator of the Harry had to shift the company’s focus towards business model was designed to Potter character, J.K. Rowling. Universal innovation and customer centricity in accommodate farmers, intermediaries in and Disney have been competing in the addition to posting continued growth in a the traditional model and the company entertainment industry for many years, and sluggish economy. The case study discusses through information technology. The main Walt Disney had been a leader in theme Immelt’s innovation and customer centric objective of e-Choupal is dissemination and parks. -

From Theleague

LINES from the League The Student and Alumni Magazine of the Art Students League of New York Spring 2014 Letter from the Executive Director here has always been a welcoming spirit at the League. Those with an affinity for art know that they are with like-minded people who share T their goals and desires to master their mediums. In such a supportive environment, many of our students choose to remain and study years after first enrolling. In this regard, we are as much a community as we are a school. This is the nature of the League: there are as many reasons to attend the League as there are attending students. The Board and administration recognize the League’s primary mission of providing a program and setting that supports the individual pursuit of art. The outgrowth of our 140-year history is nothing short of staggering; more promi- nent artists studied at the League than in any other institution. The same holds true for our illustrious faculty. League members who credit the League with providing them the most rewarding time of their lives continue to support us through gifts and bequests. We continue to be a sanctuary for artistic discourse and discovery where students learn that there are no limits to what they can achieve through dedication and the practice of making art. We honor those who have shown such dedication. In this issue of Lines, we profile individuals such as instructor Bruce Dorfman, celebrating fifty years of teaching at the League, and artist Eleanor Adam, who came to the League after the death of her son Alex to learn art and rediscover her place in the world. -

Manufacturing the Future of 3D Printing

INSIDE • James Cameron: Blockbuster Businessman • Brad Feld: Turning Computers Into More Useful Tools • Terry Wohlers: Manufacturing The Future Of 3D Printing • Word On The Street • Emerging Tech Portfolio Forbes/Wolfe Emerging Tech Volume 10/ Number 11 / November 2011 www.forbesnanotech.com REPORT James Cameron: Blockbuster Businessman The Insider JOSH WOLFE, EDITOR ames Cameron is an award- winning director, producer, s we go into the holi- Jscreenwriter, environmental- A day season, we bring ist and entrepreneur. Over the you a very special gift. On last 20 years, he has written and top of revealing one of the directed some of the largest hottest new emerging tech- blockbuster movies of all time, nology areas, we sit for a including The Terminator, Aliens, rare and exclusive interview The Abyss, Titanic and most re - with a very special friend cently, Avatar . His films have and guest. He is a lifelong pushed the limits of special ef - learner, technology tinkerer, fects, and his fascination with visual visionary and a six- technical developments led him time Academy Award nomi- to co-create the 3-D Fusion nee responsible for the two Camera System. He has also con- highest-grossing films of all tributed to new techniques in time (nearly $2B for Titanic underwater filming and remote and $3B for Avatar ): James vehicle technology. Cameron’s JAMES CAMERON Cameron. Inspired in part first job was as a truck driver and by his father (an electrical he wrote only in his spare time. After seeing Star Wars, he quit that job and wrote his first science fiction engineer) and originally script for a ten-minute short calledXenogenesis . -

Awakening to Mortality: End-Of-Life As Rite of Passage and Pathway to Transformation

Awakening to Mortality: End-of-Life as Rite of Passage and Pathway to Transformation The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Grey, Joan S. 2019. Awakening to Mortality: End-of-Life as Rite of Passage and Pathway to Transformation. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42006729 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Awakening to Mortality: End-of-life as Rite of Passage and Pathway to Transformation Joan S. Grey A Thesis in the Field of Religion for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2019 2 Copyright 2019 [Joan S. Grey] Abstract Many view death as catastrophe, resulting from a cascading failure of biological systems. Fear, denial or unconsciousness results in a medicalized, often institutionalized, approach to end-of-life care. Is dying predominantly a medical event or can it be something more? What would it take to approach end-of-life with intentionality, dignity, and integrity, consistent with beliefs and values? Is healing possible when curing disease is no longer an option? Given the embeddedness of the scientific model in our culture, my thesis “Awakening to Mortality: End-of-life as Rite of Passage and Pathway to Transformation” uses medical terminology for chapter headings -- diagnosis, prognosis and treatment -- as a structure to examine end-of-life. -

Why Tech Companies Fail to Jump the Financial S-Curve

Why Tech Companies Fail to Jump the Financial S-Curve By Alok Ranjan Singh SUBMITTED TO THE MIT SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2016 ©2016 Alok Ranjan Singh. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: ____________________________________________________________ MIT Sloan School of Management May 6, 2016 Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ Duncan Simester NTU Professor of Marketing Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: ___________________________________________________________________ Stephen Sacca Director, MIT Sloan Fellows Program in Innovation and Global Leadership MIT Sloan School of Management WHY TECH COMPANIES FAIL TO JUMP THE FINANCIAL S-CURVE Why Tech Companies Fail to Jump the Financial S-Curve By Alok Ranjan Singh Submitted to MIT Sloan School of Management on May 6, 2016 in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Business Administration Abstract The rules of the game in the globalized business environment have changed. In the Information Technology (IT) industry, starting as a new company with a new offering or business model, climbing the upward growth trajectory of financial results, and later getting stuck in a flat or declining graph has been a common pattern for many companies. Many of them have failed to jump the financial S-curve, create and climb a new one. To address this, I have referred to seminal works, have gained insights from experts, have captured inputs from corporate leaders, have consulted academicians, and have discussed with fellow Sloan Fellows. -

Postfix, Past Present and Future

IBM Research Postfix, past present and future Wietse Venema IBM T. J. Watson Research Center Hawthorne, NY, USA © 2010 IBM Corporation IBM Research Postfix in a nutshell . Who runs Postfix: – Providers with 10+M mailboxes (Outblaze, UOL). – Desktops & servers (MacOS X, Ubuntu, NetBSD). – Appliances (Brightmail, Frontbridge, etc.). Who provides Postfix: – Yours truly, helped by small number of volunteers with input from a small core of active users. – Code contributions are accepted. Sometimes as is, usually after some editing. 2 Postfix, past present and future © 2010 IBM Corporation IBM Research Overview . Publicity makes a big difference. Why (not) write another UNIX mail system. Postfix implementation. Extensibility as a proverbial life saver. Catching up on Sendmail. Lies, d*mned lies, and market share. Work in progress: postscreen. Conclusion. 3 Postfix, past present and future © 2010 IBM Corporation IBM Research . Publicity makes a difference “[Releasing SATAN is] like distributing high-powered rocket launchers throughout the world, free of charge, available at your local library or school.” San Jose Mercury, 1995 4 Postfix, past present and future © 2010 IBM Corporation IBM Research SHARING SOFTWARE, IBM TO RELEASE MAIL PROGRAM BLUEPRINT By JOHN MARKOFF - - - The program, Secure Mailer, serves as an electronic post office for server computers connected to the Internet. It was developed by Wietse Venema, an IBM researcher and computer security specialist. - - - Currently about 70 percent of all e-mail worldwide is handled by Sendmail, a program that has been developed over more. New York Times Business Section, December 1998. Publicity makes a difference 5 Postfix, past present and future © 2010 IBM Corporation IBM Research Postfix (Secure Mailer) project .