From Theleague

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton Easter Fiel

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Oral History Interview with Eugenie Gershoy, 1964 Oct. 15

Oral history interview with Eugenie Gershoy, 1964 Oct. 15 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview EG:: EUGENIE GERSHOY MM:: MARY McCHESNEY RM:: ROBERT McCHESNEY (Miss Gershoy was on the WPA sculpture project in New York City) MM:: First I'd like to ask you, Johnny -- isn't that your nickname? -- where were you born? EG:: In Russia. MM:: What year? EG:: 1901. MM:: What town were you born in? EG:: In a wonderful little place called Krivoi Rog. It's a metal-lurgical center that was very important in the second World War. A great deal of fighting went on there, and it figured very largely in the German-Russian campaign. MM:: When did you come to the United States? EG:: 1903. MM:: You were saying that you came to the United States in 1903, so you were only two years old. EG:: Yes. MM:: Where did you receive your art training? EG:: Very briefly, I had a couple of scholarships to the Art Students League. MM:: In New York City? EG:: Yes. And then I got married and went to Woodstock and worked there by myself. John Flanagan, the sculptor, was a great friend of ours, and he was up there, too. I was very much influenced by him. He used to take the boulders in the field and make his sculptures of them, and also the wood that was indigenous to the neighborhood -- ash, pine, apple wood, and so forth. -

WIKINOMICS How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything

WIKINOMICS How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything EXPANDED EDITION Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams Portfolio Praise for Wikinomics “Wikinomics illuminates the truth we are seeing in markets around the globe: the more you share, the more you win. Wikinomics sheds light on the many faces of business collaboration and presents a powerful new strategy for business leaders in a world where customers, employees, and low-cost producers are seizing control.” —Brian Fetherstonhaugh, chairman and CEO, OgilvyOne Worldwide “A MapQuest–like guide to the emerging business-to-consumer relation- ship. This book should be invaluable to any manager—helping us chart our way in an increasingly digital world.” —Tony Scott, senior vice president and chief information officer, The Walt Disney Company “Knowledge creation happens in social networks where people learn and teach each other. Wikinomics shows where this phenomenon is headed when turbocharged to engage the ideas and energy of customers, suppli- ers, and producers in mass collaboration. It’s a must-read for those who want a map of where the world is headed.” —Noel Tichy, professor, University of Michigan and author of Cycle of Leadership “A deeply profound and hopeful book. Wikinomics provides compelling evidence that the emerging ‘creative commons’ can be a boon, not a threat to business. Every CEO should read this book and heed its wise counsel if they want to succeed in the emerging global economy.” —Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman, World Economic Forum “Business executives who want to be able to stay competitive in the future should read this compelling and excellently written book.” —Tiffany Olson, president and CEO, Roche Diagnostics Corporation, North America “One of the most profound shifts transforming business and society in the early twenty-first century is the rapid emergence of open, collaborative innovation models. -

The Application Usage and Risk Report an Analysis of End User Application Trends in the Enterprise

The Application Usage and Risk Report An Analysis of End User Application Trends in the Enterprise 8th Edition, December 2011 Palo Alto Networks 3300 Olcott Street Santa Clara, CA 94089 www.paloaltonetworks.com Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 Demographics ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Social Networking Use Becomes More Active ................................................................ 5 Facebook Applications Bandwidth Consumption Triples .......................................................................... 5 Twitter Bandwidth Consumption Increases 7-Fold ................................................................................... 6 Some Perspective On Bandwidth Consumption .................................................................................... 7 Managing the Risks .................................................................................................................................... 7 Browser-based Filesharing: Work vs. Entertainment .................................................... 8 Infrastructure- or Productivity-Oriented Browser-based Filesharing ..................................................... 9 Entertainment Oriented Browser-based Filesharing .............................................................................. 10 Comparing Frequency and Volume of Use -

Emerging Trends in Management, IT and Education ISBN No.: 978-87-941751-2-4

Emerging Trends in Management, IT and Education ISBN No.: 978-87-941751-2-4 Paper 3 A STUDY ON REINVENTION AND CHALLENGES OF IBM Kiran Raj K. M1 & Krishna Prasad K2 1Research Scholar College of Computer Science and Information Science, Srinivas University, Mangalore, India 2 College of Computer Science and Information Science, Srinivas University, Mangalore, India E-mail: [email protected] Abstract International Business Machine Corporation (IBM) is one of the first multinational conglomerates to emerge in the US-headquartered in Armonk, New York. IBM was established in 1911 in Endicott, New York, as Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR). In 1924, CTR was renamed IBM. Big Blue has been IBM's nickname since 19 80. IBM stared with the production of scales, punch cards, data processors and time clock now produce and sells computer hardware and software, middleware, provides hosting and consulting services.It has a worldwide presence, operating in over 175 nations with 3,50,600 staff with $79. 6 billion in annual income (Dec 2018). It is currently competing with Microsoft, Google, Apple, and Amazon. 2012 to 2017 was tough time for IBM, although it invests in the field of research where it faced challenges while trying to stay relevant in rapidly changing Tech-Market. While 2018 has been relatively better and attempting to regain its place in the IT industry. With 3,000 scientists, it invests 7% of its total revenue to Research & Development in 12 laboratories across 6 continents. This resulted in the U.S. patent leadership in IBM's 26th consecutive year. In 2018, out of the 9,100 patents that granted to IBM 1600 were related to Artificial Intelligence and 1,400 related to cyber-security. -

UNIT CONVERSION FACTORS Temperature K C 273 C 1.8(F 32

Source: FUNDAMENTALS OF MICROSYSTEMS PACKAGING UNIT CONVERSION FACTORS Temperature K ϭ ЊC ϩ 273 ЊC ϭ 1.8(ЊF Ϫ 32) ЊR ϭ ЊF ϩ 460 Length 1 m ϭ 1010 A˚ ϭ 3.28 ft ϭ 39.4 in Mass 1 kg ϭ 2.2 lbm Force 1 N ϭ 1 kg-m/s2 ϭ 0.225 lbf Pressure (stress) 1 P ϭ 1 N/m2 ϭ 1.45 ϫ 10Ϫ4 psi Energy 1 J ϭ 1W-sϭ 1 N-m ϭ 1V-C 1Jϭ 0.239 cal ϭ 6.24 ϫ 1018 eV Current 1 A ϭ 1 C/s ϭ 1V/⍀ CONSTANTS Avogadro’s Number 6.02 ϫ 1023 moleϪ1 Gas Constant, R 8.314 J/(mole-K) Boltzmann’s constant, k 8.62 ϫ 10Ϫ5 eV/K Planck’s constant, h 6.63 ϫ 10Ϫ33 J-s Speed of light in a vacuum, c 3 ϫ 108 m/s Electron charge, q 1.6 ϫ 10Ϫ18 C SI PREFIXES giga, G 109 mega, M 106 kilo, k 103 centi, c 10Ϫ2 milli, m 10Ϫ3 micro, 10Ϫ6 nano, n 10Ϫ9 Downloaded from Digital Engineering Library @ McGraw-Hill (www.digitalengineeringlibrary.com) Copyright © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved. Any use is subject to the Terms of Use as given at the website. Source: FUNDAMENTALS OF MICROSYSTEMS PACKAGING CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO MICROSYSTEMS PACKAGING Prof. Rao R. Tummala Georgia Institute of Technology ................................................................................................................. Design Environment IC Thermal Management Packaging Single Materials Chip Opto and RF Functions Discrete Passives Encapsulation IC Reliability IC Assembly Inspection PWB MEMS Board Manufacturing Assembly Test Downloaded from Digital Engineering Library @ McGraw-Hill (www.digitalengineeringlibrary.com) Copyright © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies. -

Oral History Interview with Katherine Schmidt, 1969 December 8-15

Oral history interview with Katherine Schmidt, 1969 December 8-15 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Katherine Schmidt on December 8 & 16, 1969. The interview took place in New York City, and was conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview DECEMBER 8, 1969 [session l] PAUL CUMMINGS: Okay. It's December 8, 1969. Paul Cummings talking to Katherine Schubert. KATHERINE SCHMIDT: Schmidt. That is my professional name. I've been married twice and I've never used the name of my husband in my professional work. I've always been Katherine Schmidt. PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, could we start in 0hio and tell me something about your family and how they got there? KATHERINE SCHMIDT: Certainly. My people on both sides were German refugees of a sort. I would think you would call them from the troubles in Germany in 1848. My mother's family went to Lancaster, Ohio. My father's family went to Xenia, Ohio. When my father as a young man first started out in business and was traveling he was asked to go to see an old friend of his father's in Lancaster. And there he met my mother, and they were married. My mother then returned with him to Xenia where my sister and I were born. -

The Finding Aid to the Alf Evers Archive

FINDING AID TO THE ALF EVERS’ ARCHIVE A Account books & Ledgers Ledger, dark brown with leather-bound spine, 13 ¼ x 8 ½”: in front, 15 pp. of minutes in pen & ink of meetings of officers of Oriental Manufacturing Co., Ltd., dating from 8/9/1898 to 9/15/1899, from its incorporation to the company’s sale; in back, 42 pp. in pencil, lists of proverbs; also 2 pages of proverbs in pencil following the minutes Notebook, 7 ½ x 6”, sold by C.W. & R.A. Chipp, Kingston, N.Y.: 20 pp. of charges & payments for goods, 1841-52 (fragile) 20 unbound pages, 6 x 4”, c. 1837, Bastion Place(?), listing of charges, payments by patrons (Jacob Bonesteel, William Britt, Andrew Britt, Nicolas Britt, George Eighmey, William H. Hendricks, Shultis mentioned) Ledger, tan leather- bound, 6 ¾ x 4”, labeled “Kingston Route”, c. 1866: misc. scattered notations Notebook with ledger entries, brown cardboard, 8 x 6 ¼”, missing back cover, names & charges throughout; page 1 has pasted illustration over entries, pp. 6-7 pasted paragraphs & poems, p. 6 from back, pasted prayer; p. 23 from back, pasted poems, pp. 34-35 from back, pasted story, “The Departed,” 1831-c.1842 Notebook, cat. no. 2004.001.0937/2036, 5 1/8 x 3 ¼”, inscr. back of front cover “March 13, 1885, Charles Hoyt’s book”(?) (only a few pages have entries; appear to be personal financial entries) Accounts – Shops & Stores – see file under Glass-making c. 1853 Adams, Arthur G., letter, 1973 Adirondack Mountains Advertisements Alderfer, Doug and Judy Alexander, William, 1726-1783 Altenau, H., see Saugerties, Population History files American Revolution Typescript by AE: list of Woodstock residents who served in armed forces during the Revolution & lived in Woodstock before and after the Revolution Photocopy, “Three Cemeteries of the Wynkoop Family,” N.Y. -

DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2

Flash 6X9 / DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2 DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration 00-FM.indd 1 9/17/13 2:26 PM Flash 6X9 / DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2 00-FM.indd 2 9/17/13 2:26 PM Flash 6X9 / DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2 DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration Paul Zikopoulos Sam Lightstone Matt Huras Aamer Sachedina George Baklarz New York Chicago San Francisco Athens London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi Singapore Sydney Toronto 00-FM.indd 3 9/17/13 2:26 PM Flash 6X9 / DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration / Zikopoulos / 349-2 McGraw-Hill Education books are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative, please visit the Contact Us pages at www.mhprofessional.com. DB2 10.5 with BLU Acceleration: New Dynamic In-Memory Analytics for the Era of Big Data Copyright © 2014 by McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. Printed in the Unit- ed States of America. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of pub- lisher, with the exception that the program listings may be entered, stored, and exe- cuted in a computer system, but they may not be reproduced for publication. All trademarks or copyrights mentioned herein are the possession of their respective owners and McGraw-Hill Education makes no claim of ownership by the mention of products that contain these marks. -

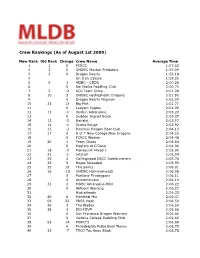

Ranking System.Xlsx

Crew Rankings (As of August 1st 2009) New Rank Old Rank Change Crew Name Average Time 1 1 0 FCRCC 1:57.62 2 2 0 OHDBC Mayfair Predators 1:59.09 3 3 0 Dragon Beasts 1:59.18 4 On S'en Calisse 1:59.25 561ADBC - CSDC 2:00.26 6 0 Kai Ikaika Paddling Club 2:00.73 7 5 -2 SCC Team Chiro 2:01.28 8 10 2 OHDBC Hydrophobic Dragons 2:01.90 9 0 Dragon Hearts Magnum 2:02.59 10 23 13 Big Fish 2:02.77 11 0 Laoyam Eagles 2:02.99 12 11 -1 Verdun Adrenaline 2:03.22 13 0 Sudden Impact Black 2:03.37 14 12 -2 Hanalei 2:03.57 15 14 -1 Scotia Rouge 2:03.92 16 13 -3 Piranhas Dragon Boat Club 2:04.13 17 17 0 U of T New College New Dragons 2:04.25 18 0 FCRCC Women 2:04.48 19 20 1 Team Chaos 2:04.84 20 0 Masters of D'Zone 2:04.96 21 19 -2 Manayunk Mixed I 2:05.00 22 21 -1 Jetstart 2:05.04 23 25 2 Collingwood DBCC Sidelaunchers 2:05.76 24 29 5 Mojos Reloaded 2:05.95 25 35 10 The Saints 2:06.01 26 16 -10 OHDBC Hammerheads 2:06.08 27 0 Portland Firedragons 2:06.11 28 0 Anniemaniacs 2:06.14 29 31 2 MDBC Adrenaline-HRV 2:06.22 30 0 Without Warning 2:06.27 31 HydraHeads 2:06.33 32 40 8 Montreal Mix 2:06.47 33 56 23 PDBC Heat 2:06.50 34 36 2 The Blades 2:06.50 35 38 3 DCH DVP 2:06.56 36 0 San Francisco Dragon Warriors 2:06.60 37 0 Victoria College Paddling Club 2:06.66 38 52 14 MOFO''s 2:06.68 39 0 Philadelphia Police Boat Teams 2:06.75 40 33 -7 TECO Tan Anou Black 2:06.78 41 41 0 3R Dragon - Mixed 2:07.19 42 37 -5 TECO Tan Anou Red 2:07.20 43 49 6 University Elite Force 2:07.27 44 39 -5 Mayfair Warriors 2:07.39 45 51 6 Hydroblades 2:07.39 46 24 -22 PDBC 2:07.79 47 0 UC -

Oral History Interview with Raphael Soyer, 1981 May 13-June 1

Oral history interview with Raphael Soyer, 1981 May 13-June 1 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Funding for this interview was provided by the Wyeth Endowment for American Art. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Raphael Soyer on May 13, 1981. The interview was conducted by Milton Brown for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Tape 1, side A MILTON BROWN: This is an interview with Raphael Soyer with Milton Brown interviewing. Raphael, we’ve known each other for a very long time, and over the years you have written a great deal about your life, and I know you’ve given many interviews. I’m doing this especially because the Archives wants a kind of update. It likes to have important American artists interviewed at intervals, so that as time goes by we keep talking to America’s famous artists over the years. I don’t know that we’ll dig anything new out of your past, but let’s begin at the beginning. See if we can skim over the early years abroad and coming here in general. I’d just like you to reminisce about your early years, your birth, and how you came here. RAPHAEL SOYER: Well, of course I was born in Russia, in the Czarist Russia, and I came here in 1912 when I was twelve years old. -

Post Sale Results for 684 - Palm Beach Single Owner Fine Art Online May 14, 2019

Post Sale Results for 684 - Palm Beach Single Owner Fine Art Online May 14, 2019 Lot and Description Low High Price Realized 1 - Jack Levine, (American, 1915-2010) etching and drypoint signed and $300 $500 $187 numbered 82/100 2 - Walt Francis Kuhn, (American, 1877-1949) lithograph signed in pencil $200 $300 $125 (lower left) 3 - Isabel Bishop, (American, 1902-1988) etching signed in pencil (lower $600 $900 $406 right) 5 - Robert Kushner, (American, born 1949) oil on canvas $1,000 $1,500 $1,062 6 - Hal Larsen, (American, born 1935) watercolor, collage on board signed $600 $800 Unsold (lower right) 7 - Leo Meisser, (Swiss, 1902-1977) etching signed and numbered 26/55 $100 $150 $62 8 - Victoria Ebbels Hutson Hartley, (American, 1900-1971) pencil on paper $200 $300 $125 signed, dedicated and dated (lower margin) 9 - Walt Francis Kuhn, (American, 1877-1949) ink and wash on paper $500 $700 $625 10 - Jack Levine, (American, 1915-2010) mezzotint signed and numbered $200 $300 $125 69/100 11 - Peggy Bacon, (American, 1895-1987) lithograph signed and titled in $150 $200 $281 pencil (lower margin) 12 - Isabel Bishop, (American, 1902-1988) ink on paper signed (lower left) $300 $500 $625 13 - Jack Levine, (American, 1915-2010) brown wash on paper signed $600 $800 Unsold (lower right) 14 - Walt Francis Kuhn, (American, 1877-1949) ink on paper $500 $700 Unsold 15 - Isabel Bishop, (American, 1902-1988) oil and watercolor on panel $8,000 $10,000 $13,750 signed (upper right) 16 - Walt Francis Kuhn, (American, 1877-1949) lithograph signed and titled $150 $200 $162 (lower margin 17 - Robert Kushner, (American, born 1949) acrylic, metal leaf and glitter $800 $1,000 $1,000 signed, titled and dated (lower left) 18 - Mary Frank, (English/American, b.