The Commoner Issue 13 Winter 2008-2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JWOS Vol 10.Indd

12 “To Free-Town, Our Common Judgement Place”: Commoners in Romeo and Juliet Barbara Mather Cobb Murray State University lthough the bulk of Shakespeare’s plays open with characters of the noble class on stage, fi ve open with commoners. A In each case, the commoner characters direct our gaze and focus our attention on the issue at hand. The device is used frequently throughout Shakespeare’s canon: the commoner character is presented matter-of-factly and sympathetically, with little affect and sometimes with little development, and thus serves a similar role to that of the Chorus in a Sophocles play, leading a commoner audience member to recognize the nature of the confl ict in the play at hand. In Coriolanus we meet an angry crowd, Citizens who are starving and who blame Caius Martius, who will become Coriolanus, for their condition. Although some scholars argue for an ambivalent audience response to this protagonist, using evidence from points later in the play, a commoner audience member would be attuned to his fl aw, his culpability, his propensity toward ego and selfi shness because they identify with the commoners who describe him this way in this fi rst interaction with these characters. Timon of Athens and Julius Caesar both begin with tradesmen: in Timon, a Poet, Painter, Jeweler, and Mercer comment on Fortune and on those whom Fortune favors, like Timon, already precursing his fall as Fortune’s wheel turns; in Julius Caesar, a Carpenter and Cobbler celebrate Caesar, prepossessing the audience toward compassion for the leader besieged by other leaders envious of his power and popularity. -

William Jennings Bryan and His Opposition to American Imperialism in the Commoner

The Uncommon Commoner: William Jennings Bryan and his Opposition to American Imperialism in The Commoner by Dante Joseph Basista Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2019 The Uncommon Commoner: William Jennings Bryan and his Opposition to American Imperialism in The Commoner Dante Joseph Basista I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Dante Basista, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Donna DeBlasio, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT This is a study of the correspondence and published writings of three-time Democratic Presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan in relation to his role in the anti-imperialist movement that opposed the US acquisition of the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico following the Spanish-American War. Historians have disagreed over whether Bryan was genuine in his opposition to an American empire in the 1900 presidential election and have overlooked the period following the election in which Bryan’s editorials opposing imperialism were a major part of his weekly newspaper, The Commoner. The argument is made that Bryan was authentic in his opposition to imperialism in the 1900 presidential election, as proven by his attention to the issue in the two years following his election loss. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

A FILM by Götz Spielmann Nora Vonwaldstätten Ursula Strauss

Nora von Waldstätten Ursula Strauss A FILM BY Götz Spielmann “Nobody knows what he's really like. In fact ‘really‘ doesn't exist.” Sonja CONTACTS OCTOBER NOVEMBER Production World Sales A FILM BY Götz Spielmann coop99 filmproduktion The Match Factory GmbH Wasagasse 12/1/1 Balthasarstraße 79-81 A-1090 Vienna, Austria D-50670 Cologne, Germany WITH Nora von Waldstätten P +43. 1. 319 58 25 P +49. 221. 539 709-0 Ursula Strauss F +43. 1. 319 58 25-20 F +49. 221. 539 709-10 Peter Simonischek E [email protected] E [email protected] Sebastian Koch www.coop99.at www.matchfactory.de Johannes Zeiler SpielmannFilm International Press Production Austria 2013 Kettenbrückengasse 19/6 WOLF Genre Drama A-1050 Vienna, Austria Gordon Spragg Length 114 min P +43. 1. 585 98 59 Laurin Dietrich Format DCP, 35mm E [email protected] Michael Arnon Aspect Ratio 1:1,85 P +49 157 7474 9724 Sound Dolby 5.1 Festivals E [email protected] Original Language German AFC www.wolf-con.com Austrian Film Commission www.oktober-november.at Stiftgasse 6 A-1060 Vienna, Austria P +43. 1. 526 33 23 F +43. 1. 526 68 01 E [email protected] www.afc.at page 3 SYNOPSIS In a small village in the Austrian Alps there is a hotel, now no longer A new chapter begins; old relationships are reconfigured. in use. Many years ago, when people still took summer vacations The reunion slowly but relentlessly brings to light old conflicts in such places, it was a thriving business. -

The Distribution of Bolivia's Most Important Natural Resources And

Issue Brief • July 2008 The Distribution of Bolivia’s Most Important Natural Resources and the Autonomy Conflicts BY MARK WEISBROT AND LUIS SANDOVAL * Over the last year, there has been an escalation in the political battles between the government of President Evo Morales and a conservative opposition, based primarily in the prefectures, or provinces. The opposition groups have rallied around various issues but have recently begun to focus on "autonomy." Some of the details of this autonomy are legally complex and ambiguous, and they vary among the provinces whose governments are demanding autonomy. Since May of this year, four prefectures – Santa Cruz, Beni, Pando, and Tarija, which are often referred to as the "Media Luna" 1 – have held referenda, which were ruled illegal by the national judiciary, 2 in which a majority of those voting voted in favor of autonomy statutes. While there are a number of political and ideological aspects to this conflict, this paper focuses on one of the most important underlying sources of the dispute: the distribution of Bolivia's most important natural resources. For reasons described below, these are arable land and hydrocarbons. This paper shows that the ownership and distribution of these key resources are at the center of the current conflict. Furthermore, it appears that reform of this ownership and distribution may be necessary for the government to deliver on its political promise to improve the living standards of the country's poor majority, who are also disproportionately indigenous. According to the most recent data, Bolivia has a poverty rate of 60 percent. The number of people in extreme poverty is about 38 percent (UDAPE, 2008). -

THESIS NO MORALES Corrections

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/2047 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Andreas Tsolakis Globalisation and the reform of the Bolivian state, 1985-2005 Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics and International Studies University of Warwick March 2009 2 Table of Contents Illustrations and tables 3 Acknowledgments 5 Abbreviations and acronyms 6 Abstract 10 Chapter 1: Introduction 12 Chapter 2: The state as contradictory organisation of subjection 59 Chapter 3: The National Revolution, state capitalism and crisis 92 Chapter 4: The transnational historic bloc and global restructuring 125 Chapter 5: The internationalisation of the Bolivian state, 1985-2005 172 Chapter 6: Polyarchy in Bolivia, 1985-2005 221 Chapter 7: Conclusion 267 Appendix 1: Selected economic indicators 279 Appendix 2: Bolivian state map 286 Appendix 3: List of interviewees 287 Notes 289 Bibliography 322 3 Illustrations and Tables Tables : 1.1 Bolivian governments, 1985-2005. 3.1 Bolivian governments, 1951-1985. 3.2 Capital flight during Banzerato and democratic transition era. 3.3 Fixed investment, as percentage of GDP 1970-1985. 3.4 Pre-transition election results (% vote; major parties only). 4.1 Relative importance of major state-owned enterprises 1990. -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Chapter 3: the Rise of the Antinuclear Power Movement: 1957 to 1989

Chapter 3 THE RISE OF THE ANTINUCLEAR POWER MOVEMENT 1957 TO 1989 In this chapter I trace the development and circulation of antinuclear struggles of the last 40 years. What we will see is a pattern of new sectors of the class (e.g., women, native Americans, and Labor) joining the movement over the course of that long cycle of struggles. Those new sectors would remain autonomous, which would clearly place the movement within the autonomist Marxist model. Furthermore, it is precisely the widening of the class composition that has made the antinuclear movement the most successful social movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Although that widening has been impressive, as we will see in chapter 5, it did not go far enough, leaving out certain sectors of the class. Since its beginnings in the 1950s, opposition to the civilian nuclear power program has gone through three distinct phases of one cycle of struggles.(1) Phase 1 —1957 to 1967— was a period marked by sporadic opposition to specific nuclear plants. Phase 2 —1968 to 1975— was a period marked by a concern for the environmental impact of nuclear power plants, which led to a critique of all aspects of nuclear power. Moreover, the legal and the political systems were widely used to achieve demands. And Phase 3 —1977 to the present— has been a period marked by the use of direct action and civil disobedience by protesters whose goals have been to shut down all nuclear power plants. 3.1 The First Phase of the Struggles: 1957 to 1967 Opposition to nuclear energy first emerged shortly after the atomic bomb was built. -

Review Of" the Dutch Gentry, 1500-1650: Family, Faith, And

Swarthmore College Works History Faculty Works History 1-1-1988 Review Of "The Dutch Gentry, 1500-1650: Family, Faith, And Fortune" By S. D. Marshall Robert S. DuPlessis Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Robert S. DuPlessis. (1988). "Review Of "The Dutch Gentry, 1500-1650: Family, Faith, And Fortune" By S. D. Marshall". American Journal Of Sociology. Volume 93, Issue 4. 993-995. DOI: 10.1086/228845 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history/246 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Review Author(s): Robert S. DuPlessis Review by: Robert S. DuPlessis Source: American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 93, No. 4 (Jan., 1988), pp. 993-995 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780624 Accessed: 11-06-2015 19:37 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

February 2018 at BFI Southbank Events

BFI SOUTHBANK EVENTS LISTINGS FOR FEBRUARY 2018 PREVIEWS Catch the latest film and TV alongside Q&As and special events Preview: The Shape of Water USA 2017. Dir Guillermo del Toro. With Sally Hawkins, Michael Shannon, Doug Jones, Octavia Spencer. Digital. 123min. Courtesy of Twentieth Century Fox Sally Hawkins shines as Elisa, a curious woman rendered mute in a childhood accident, who is now working as a janitor in a research center in early 1960s Baltimore. Her comfortable, albeit lonely, routine is thrown when a newly-discovered humanoid sea creature is brought into the facility. Del Toro’s fascination with the creature features of the 50s is beautifully translated here into a supernatural romance with dark fairy tale flourishes. Tickets £15, concs £12 (Members pay £2 less) WED 7 FEB 20:30 NFT1 Preview: Dark River UK 2017. Dir Clio Barnard. With Ruth Wilson, Mark Stanley, Sean Bean. Digital. 89min. Courtesy of Arrow Films After the death of her father, Alice (Wilson) returns to her family farm for the first time in 15 years, with the intention to take over the failing business. Her alcoholic older brother Joe (Stanley) has other ideas though, and Alice’s return conjures up the family’s dark and dysfunctional past. Writer-director Clio Barnard’s new film, which premiered at the BFI London Film Festival, incorporates gothic landscapes and stunning performances. Tickets £15, concs £12 (Members pay £2 less) MON 12 FEB 20:30 NFT1 Preview: You Were Never Really Here + extended intro by director Lynne Ramsay UK 2017. Dir Lynne Ramsay. With Joaquin Phoenix, Ekaterina Samsonov, Alessandro Nivola. -

Through FILMS 70 Years of European History Through Films Is a Product in Erasmus+ Project „70 Years of European History 1945-2015”

through FILMS 70 years of European History through films is a product in Erasmus+ project „70 years of European History 1945-2015”. It was prepared by the teachers and students involved in the project – from: Greece, Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey. It’ll be a teaching aid and the source of information about the recent European history. A DANGEROUS METHOD (2011) Director: David Cronenberg Writers: Christopher Hampton, Christopher Hampton Stars: Michael Fassbender, Keira Knightley, Viggo Mortensen Country: UK | GE | Canada | CH Genres: Biography | Drama | Romance | Thriller Trailer In the early twentieth century, Zurich-based Carl Jung is a follower in the new theories of psychoanalysis of Vienna-based Sigmund Freud, who states that all psychological problems are rooted in sex. Jung uses those theories for the first time as part of his treatment of Sabina Spielrein, a young Russian woman bro- ught to his care. She is obviously troubled despite her assertions that she is not crazy. Jung is able to uncover the reasons for Sa- bina’s psychological problems, she who is an aspiring physician herself. In this latter role, Jung employs her to work in his own research, which often includes him and his wife Emma as test subjects. Jung is eventually able to meet Freud himself, they, ba- sed on their enthusiasm, who develop a friendship driven by the- ir lengthy philosophical discussions on psychoanalysis. Actions by Jung based on his discussions with another patient, a fellow psychoanalyst named Otto Gross, lead to fundamental chan- ges in Jung’s relationships with Freud, Sabina and Emma. -

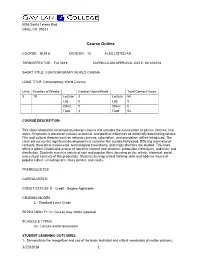

Course Outline 3/23/2018 1

5055 Santa Teresa Blvd Gilroy, CA 95023 Course Outline COURSE: HUM 6 DIVISION: 10 ALSO LISTED AS: TERM EFFECTIVE: Fall 2018 CURRICULUM APPROVAL DATE: 03/12/2018 SHORT TITLE: CONTEMPORARY WORLD CINEMA LONG TITLE: Contemporary World Cinema Units Number of Weeks Contact Hours/Week Total Contact Hours 3 18 Lecture: 3 Lecture: 54 Lab: 0 Lab: 0 Other: 0 Other: 0 Total: 3 Total: 54 COURSE DESCRIPTION: This class introduces contemporary foreign cinema and includes the examination of genres, themes, and styles. Emphasis is placed on cultural, economic, and political influences as artistically determining factors. Film and cultural theories such as national cinemas, colonialism, and orientalism will be introduced. The class will survey the significant developments in narrative film outside Hollywood. Differing international contexts, theoretical movements, technological innovations, and major directors are studied. The class offers a global, historical overview of narrative content and structure, production techniques, audience, and distribution. Students screen a variety of rare and popular films, focusing on the artistic, historical, social, and cultural contexts of film production. Students develop critical thinking skills and address issues of popular culture, including race, class gender, and equity. PREREQUISITES: COREQUISITES: CREDIT STATUS: D - Credit - Degree Applicable GRADING MODES L - Standard Letter Grade REPEATABILITY: N - Course may not be repeated SCHEDULE TYPES: 02 - Lecture and/or discussion STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Demonstrate the recognition and use of the basic technical and critical vocabulary of motion pictures. 3/23/2018 1 Measure of assessment: Written paper, written exams. Year assessed, or planned year of assessment: 2013 2. Identify the major theories of film interpretation.