Gustave Courbet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fine Arts Paris Wednesday 7 November - Sunday 11 November 2018 Carrousel Du Louvre / Paris

Fine Arts Paris WednesdAy 7 november - sundAy 11 november 2018 CArrousel du louvre / PAris press kit n o s s e t n o m e d y u g n a t www.finearts-paris.com t i d e r c Fine Arts Paris From 7 to 11 november 2018 CArrousel du louvre / PAris Fine Arts Paris From 7 to 11 november 2018 CArrousel du louvre / PAris Hours Tuesday, 6 November 2018 / Preview 3 pm - 10 pm Wednesday, 7 November 2018 / 2 pm - 8 pm Thursday 8 November 2018 / noon - 10 pm Friday 9 November 2018 / noon - 8 pm Saturday 10 November 2018 / noon - 8 pm Sunday 11 November 2018 / noon - 7 pm admission: €15 (catalogue included, as long as stocks last) Half price: students under the age of 26 FINE ARTS PARIS Press oPening Main office tuesdAy 6 november 68, Bd malesherbes, 75008 paris 2 Pm Hélène mouradian: + 33 (0)1 45 22 08 77 Social media claire Dubois and manon Girard: Art Content + 33 (0)1 45 22 61 06 Denise Hermanns contact@finearts-paris.com & Jeanette Gerritsma +31 30 2819 654 Press contacts [email protected] Agence Art & Communication 29, rue de ponthieu, 75008 paris sylvie robaglia: + 33 (0)6 72 59 57 34 [email protected] samantha Bergognon: + 33 (0)6 25 04 62 29 [email protected] charlotte corre: + 33 (0)6 36 66 06 77 [email protected] n o s s e t n o m e d y u g n a t t i d e r c Fine Arts Paris From 7 to 11 november 2018 CArrousel du louvre / PAris "We have chosen the Carrousel du Louvre as the venue for FINE ARTS PARIS because we want the fair to be a major event for both the fine arts and for Paris, and an important date on every collector’s calendar. -

CHAMPS-ELYSEES ROLL OR STROLL from the Arc De Triomphe to the Tuileries Gardens

CHAMPS-ELYSEES ROLL OR STROLL From the Arc de Triomphe to the Tuileries Gardens Don’t leave Paris without experiencing the avenue des Champs-Elysées (shahnz ay-lee-zay). This is Paris at its most Parisian: monumental side- walks, stylish shops, grand cafés, and glimmering showrooms. This tour covers about three miles. If that seems like too much for you, break it down into several different outings (taxis roll down the Champs-Elysées frequently and Métro stops are located every 3 blocks). Take your time and enjoy. It’s a great roll or stroll day or night. The tour begins at the top of the Champs-Elysées, across a huge traffic circle from the famous Arc de Triomphe. Note that getting to the arch itself, and access within the arch, are extremely challenging for travelers with limited mobility. I suggest simply viewing the arch from across the street (described below). If you are able, and you wish to visit the arch, here’s the informa- tion: The arch is connected to the top of the Champs-Elysées via an underground walkway (twenty-five 6” steps down and thirty 6” steps back up). To reach this passageway, take the Métro to the not-acces- sible Charles de Gaulle Etoile station and follow sortie #1, Champs- Elysées/Arc de Triomphe signs. You can take an elevator only partway up the inside of the arch, to a museum with some city views. To reach the best views at the very top, you must climb the last 46 stairs. For more, see the listing on page *TK. -

Syllabus Paris

Institut de Langue et de Culture Française Spring Semester 2017 Paris, World Arts Capital PE Perrier de La Bâthie / [email protected] Paris, World Capital of Arts and Architecture From the 17th through the 20th centuries Since the reign of Louis XIV until the mid-20th century, Paris had held the role of World Capital of Arts. For three centuries, the City of Light was the place of the most audacious and innovative artistic advances, focusing on itself the attention of the whole world. This survey course offers students a wide panorama on the evolution of arts and architecture in France and more particularly in Paris, from the beginning of the 17th century to nowadays. The streets of the French capital still preserve the tracks of its glorious history through its buildings, its town planning and its great collections of painting, sculpture and decorative arts. As an incubator of modernity, Paris saw the rising of a new epoch governed – for better or worse – by faith in progress and reason. As literature and science, art participated in the transformations of society, being surely its more accurate reflection. Since the French Revolution, art have accompanied political and social changes, opened to the contestation of academic practice, and led to an artistic and architectural avant-garde driven to depict contemporary experience and to develop new representational means. Creators, by their plastic experiments and their creativity, give the definitive boost to a modern aesthetics and new references. After the trauma of both World War and the American economic and cultural new hegemony, appeared a new artistic order, where artists confronted with mass-consumer society, challenging an insane post-war modernity. -

Gustave Courbet Biography

ARTIST BROCHURE Decorate Your Life™ ArtRev.com Gustave Courbet Gustave Courbet was born at Ornans on June 10, 1819. He appears to have inherited his vigorous temperament from his father, a landowner and prominent personality in the Franche-Comté region. At the age of 18 Gustave went to the Collège Royal at Besançon. There he openly expressed his dissatisfaction with the traditional classical subjects he was obliged to study, going so far as to lead a revolt among the students. In 1838 he was enrolled as an externe and could simultaneously attend the classes of Charles Flajoulot, director of the école des Beaux-Arts. At the college in Besançon, Courbet became fast friends with Max Buchon, whose Essais Poétiques (1839) he illustrated with four lithographs. In 1840 Courbet went to Paris to study law, but he decided to become a painter and spent much time copying in the Louvre. In 1844 his Self-Portrait with Black Dog was exhibited at the Salon. The following year he submitted five pictures; only one, Le Guitarrero, was accepted. After a complete rejection in 1847, the Liberal Jury of 1848 accepted all 10 of his entries, and the critic Champfleury, who was to become Courbet's first staunch apologist, highly praised the Walpurgis Night. Courbet achieved artistic maturity with After Dinner at Ornans, which was shown at the Salon of 1849. By 1850 the last traces of sentimentality disappeared from his work as he strove to achieve an honest imagery of the lives of simple people, but the monumentality of the concept in conjunction with the rustic subject matter proved to be widely unacceptable. -

Present Exhibitions

1 / 5 M U S E E E X P O S I T I O N S Grappling with the Modern Japonisms 2018 LE LOUVRE ❶ From Delacroix to the Present Day Kohei Nawa, Throne Rue de Rivoli 75001 Paris ------------------- April 11 July 13, From Thursday to to December 2018 Monday from 9 am to 6 ❶ 3 January pm 2018 13,2019 Nocturnes until 9:45 pm on Wednesdays and Fridays Closed on Tuesdays MAGNIFICENT VENICE ! ❷ GRAND PALAIS Miró, la couleur de ses rêves Venice: Europe and the Arts in the 18th Century 3, avenue du Général Eisenhower 75008 Paris October 3, September ------------------- 2018 26tn, 2018 From Thursday to ❷ Monday from 10 am to 8 February 3, January pm 2019 21st, 2019 Wednesday from 10 am to 10 pm Closed on Tuesdays Jakuchū (1716-1800) PETIT PALAIS Impressionists in London ❸ The colorful realm of living beings Avenue Winston Churchill, 75008 Paris June 21, September -------------------- 2018 15 From Tuesday to Sunday October 14, October from 10am to 6pm 2018 14th, 2018 Late opening - Friday until 9 pm 2 / 5 ❹ CENTRE POMPIDOU Le cubisme Place Georges-Pompidou, 75004 Paris October 17, ----------------------- 2018 Every day from 11 a.m. to 10 p.m. (exhibition areas February 25, close at 9 p.m.) 2019 Thursdays until 11 p.m. (only exhibitions on level 6) ❺ MUSEE D'ORSAY Picasso : Blue and Rose September 18, 2018 1 rue de la Légion January 6, d'Honneur - 75007 Paris 2019 ----------------------- Friday to Tuesday from 9:30 am to 6 pm Thursday from 9:30 am to 9:45 pm ❻ MUSEE JACQUEMART-ANDRE Caravaggio's Roman Period 158, boulevard Haussmann - 75008 Paris September -

A Reinterpretation of Gustave Courbet's Paintings of Nudes

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Compositions of Criticism: A Reinterpretation of Gustave Courbet's Paintings of Nudes Amanda M. Guggenbiller Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Guggenbiller, Amanda M., "Compositions of Criticism: A Reinterpretation of Gustave Courbet's Paintings of Nudes" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5721. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5721 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Compositions of Criticism: A Reinterpretation of Gustave Courbet’s Paintings of Nudes Amanda M. Guggenbiller Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Rhonda Reymond, Ph.D., Chair Janet Snyder, Ph.D., J. Bernard Schultz, Ph.D. School of Art and Design Morgantown, West Virginia 2014 Keywords: Gustave Courbet, Venus and Psyche, Mythology, Realism, Second Empire Copyright 2014 Amanda M. -

Belle Epoque France R. Howard Bloch Paris, May 28 to July 2, 2016

Belle Epoque France R. Howard Bloch Paris, May 28 to July 2, 2016 French S369, Humanities S214, Literature S247, You should do the reading for each week before our Tuesday meeting, when worksheets are due. The first week is an exception (worksheet due on Thursday), though here, too, you should do the reading before Tuesday. You should read Eugen Weber’s France Fin-de-Siècle before the course begins. We will distribute in Paris special assigned books for class presentation (10 minutes, 15 maximum). NB: There may be some change in the actual dates of presentations. We will meet for class on Tuesdays and Thursdays 1:15-4:15 p.m., Ecole Etoile, 38 Blvd. Raspail, Paris 7e, metro Sèvres-Babylone. We will meet for excursions on Wednesdays in the morning, and several times on Friday. Please be on time for class and for excursions. Do not bring your computer to class unless it is for the purpose of making a presentation. Absolutely no eating in the classroom. If you want to eat between 1:15 and 4:15, please do so during our break, and do not bring food into our sacred learning space, but leave it outside on the table in the hall. June 4, 12:00 Orientation, Ecole l’Etoile, 38 Blvd. Raspail, Paris 7e *Indicates reading available on the V2 server. Week I Reading: Emile Zola, Ladies Paradise; *Guy de Maupassant, “The Necklace,” “The Umbrella,” “A Day in the Country.” . Topics: The end of symbolism, realism and naturalism, feminine and masculine dress, the department store, advertising, posters, the decorative arts, the Universal Exposition of 1889, the Eiffel Tower, religion and anticlericalism, anarchism and the Dreyfus Affair. -

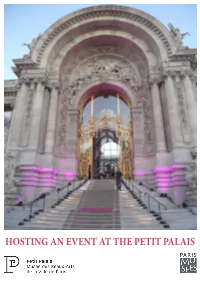

Hosting an Event at the Petit Palais Contents 2

HOSTING AN EVENT AT THE PETIT PALAIS CONTENTS 2 3 Introduction 4 Why host an event at the Petit Palais Venues and prices 5 South Gallery and Pavilion 6 Private tours of the 2nd floor’s permanent collections 7 Private tours of the temporary exhibitions 8 Organize your guided tour 9 Inner garden 10 Café - Restaurant « Le jardin du Petit Palais » 11 Auditorium 12 Corporate event packages Additional costs 13 Technician-electrician 13 Security-safety 14 Cleaning service File and procedure 15 Compile your file 16 Administrative process Useful information Contact information Museum map 19 1st floor map (street level) 20 2nd floor map (garden level) INTRODUCTION 3 Ideally located between the Invalides and the Champs-Élysées, the Petit Palais, legacy of Paris 1900’s Universal Exhibition, hosts the City of Paris’ Museum of Fine Arts, at the top of important painting, sculpture and fine art object collections from the Antiquity up to the beginning of the 20th century. Simultaneously and for more than a century, the Petit Palais has been a hot spot for great Parisian exhibitions, alternating retrospectives on historic painters or 19th century artists, and historical overviews, such as recently, Paris 1900, The City of Entertainment. The museum was entirely renovated and constitutes an example of perfect balance between modernity and 1900’s style. The Petit Palais is an exceptional typical Parisian venue, which can host top of the range events with great breadth in its South Gallery and Pavilion or more intimate ones in its beautiful inner garden and peristyle. The Petit Palais has a permanent authorization from the Police Department to organize corporate events, except fashion shows and dances. -

La Conciergerie, Une Enclave Patrimoniale Au Coeur Du Palais De

DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE 1 L’EDIFICATION DU PALAIS ROYAL PAR LES ROIS CAPETIENS Le palais royal est construit par les rois capétiens progressivement, dans un contexte de réorganisation du royaume et de réaffirmation du pouvoir monarchique. Conciergerie et Sainte-Chapelle sont les seules traces visibles de cette période, mais en fait, comme le souligne l’architecte Christophe Bottineau, les structures architecturales médiévales sont toujours là. LE SITE DU PALAIS ROYAL ET LES PREMIERES CONSTRUCTIONS L’historien Yann Potin rappelle que l’idée d’une continuité du palais de la Cité est discutable. Les plus anciens vestiges, découverts au XIXe siècle, datent en effet du XIIe siècle. La localisation d’un oppidum dans la partie occidentale de l’île, sur le site du palais, est aujourd’hui remise en cause par les archéologues, qui posent l’hypothèse d’une fondation gallo-romaine ex nihilo, à quelques kilomètres de la ville proto historique. Les rares chantiers Le palais royal de Paris, 4e lancette, de fouilles, menés principalement lors des travaux des années 1842- baie XV, Histoire des Reliques. 1898, montrent seulement la présence de demeures privées jusqu’aux IIIe et IVe siècles. La construction d’un palatium, abritant le Tribunal du prétoire et un hébergement occupé temporairement par les empereurs en campagne, est contemporaine de celles de deux ponts et des fortifications (dont un tronçon a été identifié sous la cour du Mai), édifiée lors du repli dans l’île au Bas Empire. Dans les siècles qui suivent, le palais paraît abandonné : les Mérovingiens y séjournaient peut-être, mais les sources mentionnent plutôt une résidence à Cluny ; les Carolingiens s’installent outre-Rhin, laissant probablement l’usage des lieux aux comtes. -

5-Day Paris City Guide a Preplanned Step-By-Step Time Line and City Guide for Paris

5 days 5-day Paris City Guide A preplanned step-by-step time line and city guide for Paris. Follow it and get the best of the city. 5-day Paris City Guide 2 © PromptGuides.com 5-day Paris City Guide Overview of Day 1 LEAVE HOTEL Tested and recommended hotels in Paris > Take Metro line 6 or 9 to Trocadero station 09:00-09:20 Trocadéro Gardens Romantic gardens Page 5 Take a walk through bridge Pont d’léna - 10’ 09:30-11:30 Eiffel Tower The most spectacular Page 5 view of Paris 11:30-12:00 Parc du Champ de Mars Great view on the Eiffel Page 6 tower Take a walk on Avenue de Tourville to Musée Rodin - 20’ 12:20-13:40 Musée Rodin The famous The Page 6 Thinker is on display Lunch time Take a walk to the Army Museum and Tomb of Napoleon 14:45-16:15 Army Museum and Tomb of Napoleon One of the largest Page 6 collections of military objects 16:15-16:45 Hotel des Invalides Impressive building Page 7 complex Take a walk through bridge Alexandre III - 15’ 17:00-17:20 Grand and Petit Palais Grand Palais has a Page 7 splendid glass roof 17:20-18:20 Champs-Elysées One of the most famous Page 7 streets in the world Take a walk to Arc de Triomphe - 10’ 18:30-19:15 Arc de Triomphe Breathtaking views of Page 8 Paris END OF DAY 1 © PromptGuides.com 3 5-day Paris City Guide Overview of Day 1 4 © PromptGuides.com 5-day Paris City Guide Attraction Details 09:00-09:20 Trocadéro Gardens (11, place du Trocadéro) THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW THINGS TO DO THERE Trocadéro Gardens is a 10-ha (25-acre) Walk along the romantic garden public garden opposite Eiffel tower on -

Musée Jacquemart-André - Institut De France

Communiqué de presse MUSÉE JACQUEMART-ANDRÉ - INSTITUT DE FRANCE EXPOSITION BOTTICELLI 10 SEPTEMBRE 2021 – 24 JANVIER 2022 À l’automne 2021, le musée Jacquemart-André célébrera le génie créatif de Sandro Botticelli (1445 – 1510) et l’activité de son atelier, en exposant une quarantaine d’œuvres de ce peintre raffiné accompagnées de quelques peintures de ses contemporains florentins sur lesquels Botticelli eut une influence particulière. La carrière de Botticelli, devenu l’un des plus grands artistes de Florence, témoigne du rayonnement et des changements profonds qui transforment la cité sous les Médicis. Botticelli est sans doute l’un des peintres les plus connus de la Renaissance italienne malgré la part de mystère qui entoure toujours sa vie et l’activité de son atelier. Sans relâche, il a alterné création unique et production en série achevée par ses nombreux assistants. L’exposition montrera l’importance de cette pratique d’atelier, laboratoire foisonnant d’idées et de formation, typique de la Renaissance italienne. Elle présentera Botticelli dans son rôle de créateur, mais également d’entrepreneur et de formateur. En suivant un ordre chronologique et thématique, le parcours illustrera le développement stylistique personnel de Botticelli, les liens entre son œuvre et la culture de son temps, ainsi que l’influence qu’il a lui-même exercée sur les artistes florentins du Quattrocento. vers 1490, huile sur toile, 158,1 x 68,5 cm, Photo © BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Jörg P. Anders P. / Jörg Palais RMN-Grand Dist. © BPK, Berlin, cm, Photo 158,1 x 68,5 1490, huile sur toile, vers , Vénus, , L’exposition bénéficiera de prêts d’institutions prestigieuses comme le musée du Louvre, la National Gallery de Londres, le Rijksmuseum d’Amsterdam, les musées et bibliothèques du Vatican, les Offices, la Galleria Sabauda de Turin, la Galleria dell’Accademia et le musée national du Bargello à Florence, la Gemäldegalerie de Berlin, l’Alte Pinakothek de Munich et le Städel Museum de Francfort. -

Walking Paris in Three Days : Complete Guide

Walking Paris in Three Days : Complete Guide Paris in Three Days : First Day We propose this travel guide to visit Paris in three days where the most famous places were included and some recommendations do not waste a minute of time We arrived to Paris on train to the station of Paris Gare du Nord from London. We took a public transport ( Metro).Luckily the hotel was very close. Before starting, I commented that there is an option for those who do not intend to walk: make a City Tour hop on-hop off, of which you can tour the main points of the city for one or two days. In Paris there are two very good companies: Big Bus and City Sigthseeing They see in Paris in 3 days Arc de Triomphe & Grand Palais We will start our route at the Arc de Triomphe (Charles de Gaulle-Etoile metro: lines 1, 2 and 6). We advise climbing to have a panoramic view of Paris. Once up, you can see the large avenues that start from here dividing the center of Paris, the financial district of La Defense and the famous Eiffel Tower. Booking.com From the Arc de Triomf we will walk along the avenue of the Champs Elysees, towards the side of the Place de la Concorde. Before reaching the end of the Champs Elysees we can see, on the right, the buildings of the Petit Palais and the Grand Palais, which host temporary exhibitions. more places of Paris, On the Place de la Concorde you can see an Obelisk of Egyptian origin.