A Critical Analysis of the Hare-Clark Voting System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Library of Australia Conservation Management Plan

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN A management plan complying with s.341S(1) of the EPBC Act 1999 Prepared for the National Library of Australia by Dr Michael Pearson Duncan Marshall 2012 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Conservation Management Plan (CMP), which satisfies section 341S and 341V of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), provides the framework and basis for the conservation and good management of the National Library of Australia building, in recognition of its heritage values. The National Library of Australia’s Heritage Strategy, which details the Library’s objectives and strategic approach for the conservation of heritage values, has been prepared and accepted by the then Minister on 24 August 2006. The Heritage Strategy will be reviewed during 2012 in parallel with the endorsement of this plan. The Policies in this plan support the directions of the Heritage Strategy, and indicate the objectives for identification, protection, conservation, presentation and transmission to all generations of the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place. The CMP presents the history of the creation of the National Library of Australia and the construction of its building, describes the elements that have heritage significance, and assesses that significance using the Commonwealth Heritage List criteria. The plan outlines the obligations, opportunities and constraints affecting the management and conservation of the Library. A set of conservation policies are presented, with implementation -

Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes

NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES X X I NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are respectfully advised that this book includes the names and images of people who are now deceased. Cover: Detail from Caroline Chisholm's portrait by Angelo Collen Hayter, oil on canvas, 1852, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG 459). Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes © Reserve Bank of Australia 2016 E-book ISBN 978-0-6480470-0-1 Compiled by: John Murphy Designed by: Rachel Williams Edited by: Russell Thomson and Katherine Fitzpatrick For enquiries, contact the Reserve Bank of Australia Museum, 65 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000 <museum.rba.gov.au> CONTENTS Introduction VI Portraits from the present series Portraits from pre-decimal of banknotes banknotes Banjo Paterson (1993: $10) 1 Matthew Flinders (1954: 10 shillings) 45 Dame Mary Gilmore (1993: $10) 3 Charles Sturt (1953: £1) 47 Mary Reibey (1994: $20) 5 Hamilton Hume (1953: £1) 49 The Reverend John Flynn (1994: $20) 7 Sir John Franklin (1954: £5) 51 David Unaipon (1995: $50) 9 Arthur Phillip (1954: £10) 53 Edith Cowan (1995: $50) 11 James Cook (1923: £1) 55 Dame Nellie Melba (1996: $100) 13 Sir John Monash (1996: $100) 15 Portraits of monarchs on Australian banknotes Portraits from the centenary Queen Elizabeth II of Federation banknote (2016: $5; 1992: $5; 1966: $1; 1953: £1) 57 Sir Henry Parkes (2001: $5) 17 King George VI Catherine Helen -

Compulsory Voting in Australian National Elections

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library RESEARCH BRIEF Information analysis and advice for the Parliament 31 October 2005, no. 6, 2005–06, ISSN 1832-2883 Compulsory voting in Australian national elections Compulsory voting has been part of Australia’s national elections since 1924. Renewed Liberal Party interest and a recommendation by the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters that voluntary and compulsory voting be the subject of future investigation, suggest that this may well be an important issue at the next election. This research brief refers to the origins of compulsory voting in Australia, describes its use in Commonwealth elections, outlines the arguments for and against compulsion, discusses the political impact of compulsory voting and refers to suggested reforms. Scott Bennett Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Executive summary ................................................... 3 Introduction ........................................................ 4 The emergence of compulsory voting in Australia ............................. 5 Compulsory voting elsewhere ........................................... 8 Administration of compulsory voting in Australian national elections ............... 8 To retain or reject compulsory voting? ..................................... 9 Opposition to compulsory voting ......................................... 9 Support for compulsory voting .......................................... 11 The political impact of compulsory voting -

1 Exhausted Votes

Committee Secretary Timothy McCarthy Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Dear committee, I am a software engineer living in Melbourne. Over the last few months, I have developed a tool for analysing Senate ballot papers, using raw data made available by the AEC on their website. In this submission, I will present some of my results in the hope that they might be of use to the committee, particularly in evaluating the success of changes to the recent changes to the Electoral Act. The key results are as follows: • Of the 1,042,132 exhausted votes, 917,379 (88%) were from ballots whose first preference was for a minor party or independent candidate. • 25% of the total primary vote for minor parties exhausted, compared to just 1.22% for major parties. • Nationally, donkey votes made up only 0.15% of the vote. The Division of Lingiari had an unusually high number of donkey votes (2.32%), mainly from the remote mobile teams in that division. • Despite the changes to above-the-line voting, 290,758 ballots still marked a single '1' above the line. • 1,046,837 ballots (7.56% of formal ballots) were saved from informality by savings provi- sions in the Act. 1 Exhausted votes Changes in the Electoral Act prior to the election introduced optional preferential voting both above and below the line. These changes introduced the possibility of ballots exhausting, something that was exceedingly rare under the previous rules. At the 2016 Federal election, there were just over 1 million exhausted votes, about 7.5% of the total. -

Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Inquiry Into the Conduct of the 2013 Federal Election

11 April 2014 Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Parliament House Canberra ACT Please find attached my submission to the Committee's inquiry into the conduct of the 2013 federal election. In my submission I make suggestions for changes to political party registration under the Commonwealth Electoral Act. I also suggest major changes to Senate's electoral system given the evident problems at lasty year's election as well as this year's re-run of the Western Australian Senate election. I also make modest suggestions for changes to formality rules for House of Representatives elections. I have attached a substantial appendix outlining past research on NSW Legislative Council Elections. This includes ballot paper surveys from 1999 and research on exhaustion rates under the new above the line optional preferential voting system used since 2003. I can provide the committee with further research on the NSW Legislative Council system, as well as some ballot paper research I have been carrying out on the 2013 Senate election. I am happy to discuss my submission with the Committee at a hearing. Yours, Antony Green Election Analyst Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Inquiry into the Conduct of the 2013 Federal Election Antony Green Contents Page 1. Political Party Registration 1 2. Changes to the Senate's Electoral System 7 2.1 Allow Optional Preferential Voting below the line 8 2.2 Above the Line Optional Preferential Voting 9 2.3 Hare Clark 10 2.4 Hybrid Group Ticket Option 10 2.5 Full Preferential Voting Above the Line 11 2.6 Threshold Quotas 11 2.7 Optional Preferential Voting with a Re-calculating Quota 12 2.8 Changes to Formula 12 2.9 My Suggested Solution 13 3. -

Women in the Federal Parliament

PAPERS ON PARLIAMENT Number 17 September 1992 Trust the Women Women in the Federal Parliament Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Senate Department. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Senate Department Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3061 The Department of the Senate acknowledges the assistance of the Department of the Parliamentary Reporting Staff. First published 1992 Reprinted 1993 Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Note This issue of Papers on Parliament brings together a collection of papers given during the first half of 1992 as part of the Senate Department's Occasional Lecture series and in conjunction with an exhibition on the history of women in the federal Parliament, entitled, Trust the Women. Also included in this issue is the address given by Senator Patricia Giles at the opening of the Trust the Women exhibition which took place on 27 February 1992. The exhibition was held in the public area at Parliament House, Canberra and will remain in place until the end of June 1993. Senator Patricia Giles has represented the Australian Labor Party for Western Australia since 1980 having served on numerous Senate committees as well as having been an inaugural member of the World Women Parliamentarians for Peace and, at one time, its President. Dr Marian Sawer is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Canberra, and has written widely on women in Australian society, including, with Marian Simms, A Woman's Place: Women and Politics in Australia. -

Conference of Premiers, Melbourne, March, 1898

(No. 45.) PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA. CONFERENCE OF PRl~MIERS, MELBOURNE, MARCH, 1898 : REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS. Presented to both Houses of Parliament by His Excellency's Command. Cost of printing-£! lls. (No. 45.)' CONFERENCE OF PREMIERS, HELD AT MELBOURNE, IN MARCH, 1898. Ml~UTES OF PROCEEDINGS. MONDAY, MARCH 7TH, 1898. A PRELIMINARY meeting of the Conference was held at Parliament House, Melbourne, on March 7th, 1898, at l l · 15 A.M. Present- The Right Honorable Sir Edward Braddon, K.C.M.G., Premier of Tasmania. The Right Honorable Sir John Forrest, K.C.M.G., Premier of VYestern Australia. The Right Honorable C. C. Kingston, Q.C., Premier of South Australia. The Right Honorable Sir. Hugh M. Nelson, K.C.M.G., Premier of Queensland. The Right Honorable G. H. Reid,, Premier of ~ ew South Wales. The Right Honorable Sir George Turner, K.C.M.G., Premier of Victoria. Resolved, on the motion of Mr. Reid, seconded by Mr. Kingston-That Sir George Turner, Premier of Victoria, be President of the Conference. , Mr. R. S. Rogers, Secretary to the Premifw of -Victoria, was appointed Secretary to the Conference. · The Conference then adjourned till 5 P.M. 'l'he Conference met, pursuant to adjournment, at 5 P.M. The President in the chair. Present-All the Members. The following subjects were dealt with in the manner indicated in each case:- ]. Mississippi Exhibition. Resolved-That the colonies take no part in the Exhihition. 2. Antarctic ,E.1:plord.tion. Resolved-That no joint action be taken. 3. Coinage of Silver. This suLject was discussed, and postponed for further c<)nsideration. -

The Caretaker Election

26. The Results and the Pendulum Malcolm Mackerras The two most interesting features of the 2010 election were that it was close and it was an early election. Since early elections are two-a-penny in our system, I shall deal with the closeness of the election first. The early nature of the election does, however, deserve consideration because it was early on two counts. These are considered below. Of our 43 general elections so far, this was the only one both to be close and to be an early election. Table 26.1 Months of General Elections for the Australian House of Representatives, 1901–2010 Month Number Years March 5 1901,1983, 1990, 1993, 1996 April 2 1910, 1951 May 4 1913, 1917, 1954, 1974 July 1 1987 August 2 1943, 2010 September 4 1914, 1934, 1940, 1946 October 6 1929, 1937, 1969, 1980, 1998, 2004 November 7 1925, 1928, 1958, 1963, 1966, 2001, 2007 December 12 1903, 1906, 1919, 1922, 1931, 1949, 1955, 1961, 1972, 1975, 1977, 1984 Total 43 The Close Election In the immediate aftermath of polling day, several commentators described this as the closest election in Australian federal history. While I can see why people would say that, I describe it differently. As far as I am concerned, there have been 43 general elections for our House of Representatives of which four can reasonably be described as having been close. They are the House of Representatives plus half-Senate elections held on 31 May 1913, 21 September 1940, 9 December 1961 and 21 August 2010. -

Fact Sheet 2 the FIRST COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT

Fact Sheet 2 THE FIRST COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT 1901 FEDERATION AND ’S VOTE THE PEOPLE Overview 1897-1903 Once the Australian Constitution had been accepted by voters in the Australian colonies and enacted as law by British Parliament, the process of putting the new system of federal government into practice began. The Australian colonies were now States of the Commonwealth of Australia, and the office of Governor- General represented the reigning monarch of Britain as Head of the Commonwealth. The first Governor-General of Australia, Lord Hopetoun, proclaimed the Commonwealth of Australia at a special ceremony in Centennial Park, Sydney, 1 January 1901. It was also the Governor-General’s task to commission an interim or caretaker ministry until the Australian people were able to elect their representatives to the newly created Commonwealth Parliament. These interim ministers, with Edmund Barton as Prime Minister, were sworn in as part of the inaugural ceremony at Centennial Park. Over the next 1891 first Constitutional Convention to draft months they organised the first federal election and made a federal constitution arrangements for the opening of the first Commonwealth 1893 Parliament. first ‘people’s convention’ at Corowa 1897 The first federal election delegates elected to a representative Constitutional Convention On Friday 29 March and Saturday 30 (in Queensland and South Australia) voters took part in the first election of 1898-1900 referendums on the Constitution representatives to the Parliament of the Commonwealth of held in all colonies Australia. Because there was as yet no federal electoral law, 1901 the election took place in accordance with the voting 1 January - inauguration of the legislation in each of the States. -

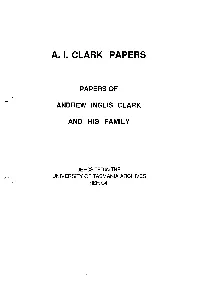

A. I. Clark Papers

A. I. CLARK PAPERS PAPERS OF r-. i - ANDREW INGLIS CLARK AND HIS FAMILY DEPOSITED IN THE UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA ARCHIVES REF:C4 - II 1_ .1 ~ ) ) AI.CLARK INDEXOF NAMES NAME AGE DESCN DATE TOPIC REF Allen,J.H. lelter C4/C9,10 Allen,Mary W. letter C4/C11,12 AspinallL,AH. 1897 Clark's resign.fr.Braddon ministry C4/C390 Barton,Edmund 1849-1920 poltn.judge,GCMG.KC 1898 federation C4/C15 Bayles,J.E. 1885 Index": Tom Paine C4/H6 Berechree c.1905 Berechree v Phoenix Assurance Cc C4/D12 Bird,Bolton Stafford 1840-1924 1885 Brighton ejection C4/C16 Blolto,Luigi of Italy 1873-4 Pacific & USA voyage C4/C17,18 Bowden 1904-6? taxation appeal C4/D10 Braddon,Edward Nicholas Coventry 1829-1904 politn.KCMG 1897 Clark's resign. C4/C390 Brown,Nicholas John MHA Tas. 1887 Clark & Moore C4/C19 Burn,William 1887 Altny Gen.appt. C4/C20 Butler,Charles lawyer 1903 solicitor to Mrs Clark C4/C21 Butler,Gilbert E. 1897 Clark's resign. .C4/C390 Camm,AB 1883 visit to AIClark C4/C22-24 Clark & Simmons lawyers 1887,1909-18 C4/D1-17,K.4,L16 Clark,Alexander Inglis 1879-1931 sAl.C.engineer 1916,21-26 letters C4/L52-58,L Clark,Alexander Russell 1809-1894 engineer 1842-6,58-63 letter book etc. C4/A1-2 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 jUdge 1870-1907 papers C4/C-J Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 judge 1901 Acting Govnr.appt. C4/E9 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848·1907 jUdge 1907-32 estate of C4/K7,L281 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 judge 1958 biog. -

Optional Preferential Voting for the Australian Senate

ELECTORAL REGULATION RESEARCH NETWORK/DEMOCRATIC AUDIT OF AUSTRALIA JOINT WORKING PAPER SERIES OPTIONAL PREFERENTIAL VOTING FOR THE AUSTRALIAN SENATE Michael Maley (Associate, Centre For Democratic Institutions, Australian National University) WORKING PAPER NO. 16 (NOVEMBER 2013) 1 Introduction This paper explores the possible use of optional preferential voting (OPV) as a way of dealing with concerns which have been crystallised at the 2013 Australian federal election about the operation of some aspects of the Senate electoral system. Its main emphasis is on the extent to which full preferential voting no longer enables voters to express their preferences truthfully, and the role which OPV could play in correcting this.1 In a number of respects, the election was remarkable. • The 40 vacancies were contested by a record number of candidates, 529. • The percentage of votes polled by parties already represented in the Parliament dropped significantly from 2010. • In five out of the six States, a candidate was elected from a party which had never previously been represented in the federal Parliament. • For the first time ever, the seats in one State, South Australia, were divided between five different parties. • In Victoria, a minor party candidate was elected after having polled only 0.5% of the first preference votes cast in the State. • In Western Australia, a partial recount of ballot papers was ordered, and in the aftermath of its conduct it was revealed by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) that some 1,375 ballot papers “all of which had been verified during the initial WA Senate count … could not be located, rechecked or verified in the recount process”. -

Papers of Sir Edmund Barton Ms51

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA PAPERS OF SIR EDMUND BARTON MS51 Manuscript Collection 1968-70, 1996 and last amended 2001 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview 3 Biographical Note 6 Related Material 8 Microfilms 9 Series Description 10 Series 1: Correspondence 1827-1921 10 Series 2: Diaries, 1869, 1902-03 39 Series 3: Personal documents 1828-1939, 1844 39 Series 4: Commissions, patents 1891-1903 40 Series 5: Speeches, articles 1898-1901 40 Series 6: Papers relating to the Federation Campaign 1890-1901 41 Series 7: Other political papers 1892-1911 43 Series 8: Notes, extracts 1835-1903 44 Series 9: Newspaper cuttings 1894-1917 45 Series 10: Programs, menus, pamphlets 1883-1910 45 Series 11: High Court of Australia 1903-1905 46 Series 12: Photographs (now in Pictorial Section) 46 Series 13: Objects 47 Name Index of Correspondence 48 Box List 61 2 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 Overview This is a Guide to the Papers of Sir Edmund Barton held in the Manuscript Collection of the National Library of Australia. As well as using this guide to browse the content of the collection, you will also find links to online copies of collection items. Scope and Content The collection consists of correspondence, personal papers, press cuttings, photographs and papers relating to the Federation campaign and the first Parliament of the Commonwealth. Correspondence 1827-1896 relates mainly to the business and family affairs of William Barton, and to Edmund's early legal and political work. Correspondence 1898-1905 concerns the Federation campaign, the London conference 1900 and Barton's Prime Ministership, 1901-1903.