Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Team Australia?': Understanding Acculturation from Multiple

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Post 2013 2018 ‘Team Australia?’: Understanding acculturation from multiple perspectives Justine Dandy Edith Cowan University Tehereh Zianian Carolyn Moylan Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013 Part of the Migration Studies Commons Dandy, J., Ziaian, T., & Moylan, C. (2018). ‘Team Australia?’: Understanding acculturation from multiple perspectives. In M. Karasawa, M. Yuki, K. Ishii, Y. Uchida, K. Sato, & W. Friedlmeier (Eds.), Venture into cross-cultural psychology: Proceedings from the 23rd Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology.Available here This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013/4985 Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Papers from the International Association for Cross- IACCP Cultural Psychology Conferences 2018 ‘Team Australia?’: Understanding Acculturation From Multiple Perspectives Justine Dandy School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Tahereh Ziaian School of Psychology, University of South Australia Carolyn Moylan Independent non-affiliated, Western Australia Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers Part of the Psychology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Dandy, J., Ziaian, T., & Moylan, C. (2018). ‘Team Australia?’: Understanding acculturation from multiple perspectives. In M. Karasawa, M. Yuki, K. Ishii, Y. Uchida, K. Sato, & W. Friedlmeier (Eds.), Venture into cross-cultural psychology: Proceedings from the 23rd Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/152/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IACCP at ScholarWorks@GVSU. -

Me Jane Tour Playbill-Final

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN, Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President Kennedy Center Theater for Young Audiences on Tour presents A Kennedy Center Commission Based on the book Me…Jane by Patrick McDonnell Adapted and Written by Patrick McDonnell, Andy Mitton, and Aaron Posner Music and Lyrics by Andy Mitton Co-Arranged by William Yanesh Choreographed by Christopher D’Amboise Music Direction by William Yanesh Directed by Aaron Posner With Shinah Brashears, Liz Filios, Phoebe Gonzalez, Harrison Smith, and Michael Mainwaring Scenic Designer Lighting Designer Costume Designer Projection Designer Paige Hathaway Andrew Cissna Helen Q Huang Olivia Sebesky Sound Designer Properties Artisan Dramaturg Casting Director Justin Schmitz Kasey Hendricks Erin Weaver Michelle Kozlak Executive Producer General Manager Executive Producer Mario Rossero Harry Poster David Kilpatrick Bank of America is the Presenting Sponsor of Performances for Young Audiences. Additional support for Performances for Young Audiences is provided by the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; Anne and Chris Reyes; and the U.S. Department of Education. Funding for Access and Accommodation Programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. Major support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by David M. Rubenstein through the Rubenstein Arts Access Program. The contents of this document do not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. " Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. -

'Out of Sight, out of Mind? Australia's Diaspora As A

Out of sight, out of mind? Australia’s diaspora as a pathway to innovation March 2018 Contents Collaborating with our diaspora .........................................................................................................3 Australian businesses’ ‘collaboration deficit’ .......................................................................................4 The diaspora as an accelerator for collaboration .................................................................................7 Understanding the Australian diaspora’s connection to Australia ......................................................14 What now? .......................................................................................................................................27 References ........................................................................................................................................30 This report has been prepared jointly with Advance. Advance is the leading network of global Australians and alumni worldwide. The many millions of Australians who have, do, or will live outside of the country represent an incredible, unique and largely untapped national resource. Its mission is to engage, connect and empower leading global Australians and Alumni; to reinvest new skills, talents and opportunities into Australia; to move the country forward. diaspora di·as·po·ra noun A diaspora is a scattered population whose origin lies within a smaller geographic locale. Diaspora can also refer to the movement of the population from -

River Murray Weekly Report for the Week Ending Wednesday, 11 July 2012

RIVER MURRAY WEEKLY REPORT FOR THE WEEK ENDING WEDNESDAY, 11 JULY 2012 Trim Ref: D12/29243 Rainfall and Inflows There were fine, dry days and cold clear nights over the Murray-Darling Basin for much of the week until a slow moving trough brought cloud and renewed rainfall over the last few days. The system delivered widespread rain across the southern two thirds of the Basin (Map 1). Highest totals were recorded in the south-east ranges, although there were also good falls further inland including the Riverina and much of western NSW. In north-east Victoria there was 86 mm at Whitlands, 76 mm at Lake William-Hovell, 71 mm at Moroka Park and 67 mm at Cheshunt. Totals in NSW included 39 mm at Gundagai and Mt Ginini and 36 mm at Burrinjuck Dam, Tumbarumba, Gilgandra and Wellington. Out west, there was 33 mm at Menindee and on the NSW-Queensland border there was 49 mm at Hungerford. The Bureau of Meteorology has forecast further rain for the region in the days ahead. There has been a good stream flow response across the upper Murray tributaries with inflows now on the rise. On the upper River Murray, the flow at Jingellic has increased to 14,700 ML/day and is expected to continue rising towards 20,000 ML/day in the next day or two. On the Ovens River, the flow at Rocky Point increased from 3,500 to 8,300 ML/day with further rises expected, while downstream at Wangaratta, the flow has increased to over 5,000 ML/day but could exceed 20,000 ML/day in the days ahead. -

Study-Newcastle-Lonely-Planet.Pdf

Produced by Lonely Planet for Study NT NewcastleDO VIBRAne of Lonely Planet’s Top 10 Cities in Best in Travel 2011 N CREATIVE A LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 L 0 F TOP C O I T TOP E I E N S O 10 CITY I N 10 CITY ! 1 B 1 E 0 S 2 2011 T L I E N V T A R 2011 PLANE LY T’S NE T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 TOP L 0 F TOP C O I T 10 CITY E I E N S O 10 CITY I N ! 2011 1 B 1 E 0 LAN S P E 2 Y T 2011 T L L ’ I S E N E V T A R N T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T E W RE HANI AKBAR st VER I » Age 22 from Saudi Arabia OL » From Saudi Arabia » Studying an International Foundation program What do you think of Newcastle? It’s so beautiful, not big not small, nice. It’s a good place for students who are studying, with a lot of nice people. -

Land Explorers As-Oheb

LAND EXPLORERS of AUSTRALIA 3 William Hovell and Hamilton Hume Governor Brisbane asked Hamilton Hume (an Australian born expert bushman and explorer) to join William Hovell (an English sea captain and expert navigator) in an expedition from Lake George to Spenser Gulf. William Hovell Hamilton Hume Instead they decided to 1786 ~ 1875 1797 ~ 1873 go to Westernport. They set out in October 1824, and after two weeks they reached the Murrumbidgee River. It was in fl ood and they waited three days to cross it. On the 8th of November they discovered the Australian Alps. Eight days later they came to a wide, deep and clear river which they named the “Hume”; it is now known as the Murray. They continued on, crossing the Ovens and Goulburn rivers as well as the southern part of the Great Dividing Range. They fi nally reached Corio Bay, near where Geelong is now, and not Westernport as they believed, which was actually some 100km to the east. They then returned to Sydney claiming that they had found Hume and Hovell crossing the Murray River in 1824. good grazing land near Westernport. Lachlan Swamps Macquarie River Lachlan River Swamps Rufus River Bathurst Darling River Murrumbidgee River Lindsay River Murray River Torrens River Hume River Hamilton Adelaide Plains Lake George Hume River Kangaroo Is Ovens River Encounter Bay Goulburn River King River Hume and Hovell 1824 Sturt 1829 Mt Disappointment Port Phillip Bay Charles Sturt In 1829 Sturt headed an expedition which was to as he thought there was an inland sea. The follow the course of the Lachlan-Murrumbidgee expedition wasn’t easy, as they had problems with river system. -

Lake Macquarie City Destination Management Plan 2018 – 2022 3

CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................... I 1. WORDS FROM OUR MAYOR ............................................................................................ 3 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... 4 1. Destination Analysis .......................................................................................................... 5 2. Destination Direction ....................................................................................................... 10 3. DESTINATION ANALYSIS ................................................................................................ 16 1. Key destination footprint ................................................................................................. 16 2. Key assets....................................................................................................................... 17 3. Key infrastructure ............................................................................................................ 19 4. Key strengths and opportunities ..................................................................................... 21 5. Visitor market and key source markets ........................................................................... 23 6. Market positioning ........................................................................................................... 26 7. Opportunities -

The Old Hume Highway History Begins with a Road

The Old Hume Highway History begins with a road Routes, towns and turnoffs on the Old Hume Highway RMS8104_HumeHighwayGuide_SecondEdition_2018_v3.indd 1 26/6/18 8:24 am Foreword It is part of the modern dynamic that, with They were propelled not by engineers and staggering frequency, that which was forged by bulldozers, but by a combination of the the pioneers long ago, now bears little or no needs of different communities, and the paths resemblance to what it has evolved into ... of least resistance. A case in point is the rough route established Some of these towns, like Liverpool, were by Hamilton Hume and Captain William Hovell, established in the very early colonial period, the first white explorers to travel overland from part of the initial push by the white settlers Sydney to the Victorian coast in 1824. They could into Aboriginal land. In 1830, Surveyor-General not even have conceived how that route would Major Thomas Mitchell set the line of the Great look today. Likewise for the NSW and Victorian Southern Road which was intended to tie the governments which in 1928 named a straggling rapidly expanding pastoral frontier back to collection of roads and tracks, rather optimistically, central authority. Towns along the way had mixed the “Hume Highway”. And even people living fortunes – Goulburn flourished, Berrima did in towns along the way where trucks thundered well until the railway came, and who has ever through, up until just a couple of decades ago, heard of Murrimba? Mitchell’s road was built by could only dream that the Hume could be convicts, and remains of their presence are most something entirely different. -

The Monarchy

The Monarchy • Elizabeth II, in full Elizabeth Alexandra Mary , officially Elizabeth II, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of her other realms and territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith • (born April 21, 1926, London, England), queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from February 6, 1952. The Role of the Monarchy • Monarchy is the oldest form of government in the United Kingdom. • In a monarchy, a king or queen is Head of State . The British monarchy is known as a constitutional monarchy . This means that, while The Sovereign is Head of State, the ability to make and pass legislation resides with an elected Parliament. • Although the British Sovereign no longer has a political or executive role, he or she continues to play an important part in the life of the nation. • As Head of State, The Monarch undertakes constitutional and representational duties which have developed over one thousand years of history. In addition to these State duties, The Monarch has a less formal role as 'Head of Nation'. The Sovereign acts as a focus for national identity, unity and pride; gives a sense of stability and continuity; officially recognises success and excellence; and supports the ideal of voluntary service. • In all these roles The Sovereign is supported by members of their immediate family. http://www.royal.gov.uk/MonarchUK/HowtheMonarchyworks/HowtheMonarchyworks.aspx Queen and Government • As Head of State The Queen has to remain strictly neutral with respect to political matters, unable to vote or stand for election. -

Indigenous Australians and Land in New South Wales

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Indigenous Australians and Land in New South Wales by Talina Drabsch Briefing Paper No 9/04 RELATED PUBLICATIONS • Aborigines, Land and National Parks in New South Wales by Stewart Smith, Briefing Paper No 2/97 • The Native Title Debate: Background and Current Issues by Gareth Griffith, Briefing Paper No 15/98 • Indigenous Issues in NSW by Talina Drabsch, Background Paper No 2/04 ISSN 1325-4456 ISBN 0 7313 1764 5 July 2004 © 2004 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Indigenous Australians and Land in New South Wales by Talina Drabsch NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE David Clune (MA, PhD, Dip Lib), Manager..............................................(02) 9230 2484 Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government / Law .........................(02) 9230 2356 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ......................(02) 9230 2768 Rowena Johns (BA (Hons), LLB), Research Officer, Law........................(02) 9230 2003 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Research Officer, Law ...................................(02) 9230 3085 Stewart Smith (BSc (Hons), MELGL), Research -

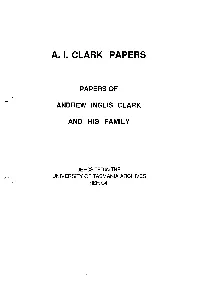

A. I. Clark Papers

A. I. CLARK PAPERS PAPERS OF r-. i - ANDREW INGLIS CLARK AND HIS FAMILY DEPOSITED IN THE UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA ARCHIVES REF:C4 - II 1_ .1 ~ ) ) AI.CLARK INDEXOF NAMES NAME AGE DESCN DATE TOPIC REF Allen,J.H. lelter C4/C9,10 Allen,Mary W. letter C4/C11,12 AspinallL,AH. 1897 Clark's resign.fr.Braddon ministry C4/C390 Barton,Edmund 1849-1920 poltn.judge,GCMG.KC 1898 federation C4/C15 Bayles,J.E. 1885 Index": Tom Paine C4/H6 Berechree c.1905 Berechree v Phoenix Assurance Cc C4/D12 Bird,Bolton Stafford 1840-1924 1885 Brighton ejection C4/C16 Blolto,Luigi of Italy 1873-4 Pacific & USA voyage C4/C17,18 Bowden 1904-6? taxation appeal C4/D10 Braddon,Edward Nicholas Coventry 1829-1904 politn.KCMG 1897 Clark's resign. C4/C390 Brown,Nicholas John MHA Tas. 1887 Clark & Moore C4/C19 Burn,William 1887 Altny Gen.appt. C4/C20 Butler,Charles lawyer 1903 solicitor to Mrs Clark C4/C21 Butler,Gilbert E. 1897 Clark's resign. .C4/C390 Camm,AB 1883 visit to AIClark C4/C22-24 Clark & Simmons lawyers 1887,1909-18 C4/D1-17,K.4,L16 Clark,Alexander Inglis 1879-1931 sAl.C.engineer 1916,21-26 letters C4/L52-58,L Clark,Alexander Russell 1809-1894 engineer 1842-6,58-63 letter book etc. C4/A1-2 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 jUdge 1870-1907 papers C4/C-J Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 judge 1901 Acting Govnr.appt. C4/E9 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848·1907 jUdge 1907-32 estate of C4/K7,L281 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 judge 1958 biog. -

CITIZENS of HEAVEN on EARTH 20Th Sunday After Pentecost (October 18 • 2020)

CITIZENS OF HEAVEN ON EARTH 20th Sunday after Pentecost (October 18 • 2020) BIBLE READING Matthew 22:15-22 REFLECTION People say that there are two things that are certain in life: death and taxes. Yes, we cannot avoid taxes as much as we cannot avoid death. Last year, a family in Tasmania was ordered by the court to pay over $2 million to the tax office. They were fined because they failed to pay income tax. They believed that paying taxes went against God’s will. For them Australian tax law was against God’s law, which was the supreme law of the land. “Transferring our allegiance from God to the Commonwealth would mean ... breaking the first commandment,” they said. They further argued that all the disasters that had happened in Australia were the results of people disobeying God’s law. But, the Judge, who gave the sentence, rightly disagreed. He reminded them that there nothing in the Bible that says, “Thou shall not pay tax!” 1 In the Judge’s view, the Bible says that “civil matters and the law of God operate in two different spheres.” 1 Unfortunately, this family’s behavior is not exclusive to them. There has always been a tendency amongst people of faith to separate themselves from the world. One of the most influential theologians in the 20th century is Richard Niebuhr He is well known for articulating five paradigms that Christians use to relate to the world: 1. Christ against culture. 2. Christ of culture. 3. Christ above culture. 4. Christ and culture in paradox.