Optional Preferential Voting for the Australian Senate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Political Parties Are Standing up for Animals?

Which political parties are standing up for animals? Has a formal animal Supports Independent Supports end to welfare policy? Office of Animal Welfare? live export? Australian Labor Party (ALP) YES YES1 NO Coalition (Liberal Party & National Party) NO2 NO NO The Australian Greens YES YES YES Animal Justice Party (AJP) YES YES YES Australian Sex Party YES YES YES Pirate Party Australia YES YES NO3 Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party YES No policy YES Sustainable Australia YES No policy YES Australian Democrats YES No policy No policy 1Labor recently announced it would establish an Independent Office of Animal Welfare if elected, however its structure is still unclear. Benefits for animals would depend on how the policy was executed and whether the Office is independent of the Department of Agriculture in its operations and decision-making.. Nick Xenophon Team (NXT) NO No policy NO4 2The Coalition has no formal animal welfare policy, but since first publication of this table they have announced a plan to ban the sale of new cosmetics tested on animals. Australian Independents Party NO No policy No policy 3Pirate Party Australia policy is to “Enact a package of reforms to transform and improve the live exports industry”, including “Provid[ing] assistance for willing live animal exporters to shift to chilled/frozen meat exports.” Family First NO5 No policy No policy 4Nick Xenophon Team’s policy on live export is ‘It is important that strict controls are placed on live animal exports to ensure animals are treated in accordance with Australian animal welfare standards. However, our preference is to have Democratic Labour Party (DLP) NO No policy No policy Australian processing and the exporting of chilled meat.’ 5Family First’s Senator Bob Day’s position policy on ‘Animal Protection’ supports Senator Chris Back’s Federal ‘ag-gag’ Bill, which could result in fines or imprisonment for animal advocates who publish in-depth evidence of animal cruelty The WikiLeaks Party NO No policy No policy from factory farms. -

Compulsory Voting in Australian National Elections

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library RESEARCH BRIEF Information analysis and advice for the Parliament 31 October 2005, no. 6, 2005–06, ISSN 1832-2883 Compulsory voting in Australian national elections Compulsory voting has been part of Australia’s national elections since 1924. Renewed Liberal Party interest and a recommendation by the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters that voluntary and compulsory voting be the subject of future investigation, suggest that this may well be an important issue at the next election. This research brief refers to the origins of compulsory voting in Australia, describes its use in Commonwealth elections, outlines the arguments for and against compulsion, discusses the political impact of compulsory voting and refers to suggested reforms. Scott Bennett Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Executive summary ................................................... 3 Introduction ........................................................ 4 The emergence of compulsory voting in Australia ............................. 5 Compulsory voting elsewhere ........................................... 8 Administration of compulsory voting in Australian national elections ............... 8 To retain or reject compulsory voting? ..................................... 9 Opposition to compulsory voting ......................................... 9 Support for compulsory voting .......................................... 11 The political impact of compulsory voting -

1 Exhausted Votes

Committee Secretary Timothy McCarthy Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Dear committee, I am a software engineer living in Melbourne. Over the last few months, I have developed a tool for analysing Senate ballot papers, using raw data made available by the AEC on their website. In this submission, I will present some of my results in the hope that they might be of use to the committee, particularly in evaluating the success of changes to the recent changes to the Electoral Act. The key results are as follows: • Of the 1,042,132 exhausted votes, 917,379 (88%) were from ballots whose first preference was for a minor party or independent candidate. • 25% of the total primary vote for minor parties exhausted, compared to just 1.22% for major parties. • Nationally, donkey votes made up only 0.15% of the vote. The Division of Lingiari had an unusually high number of donkey votes (2.32%), mainly from the remote mobile teams in that division. • Despite the changes to above-the-line voting, 290,758 ballots still marked a single '1' above the line. • 1,046,837 ballots (7.56% of formal ballots) were saved from informality by savings provi- sions in the Act. 1 Exhausted votes Changes in the Electoral Act prior to the election introduced optional preferential voting both above and below the line. These changes introduced the possibility of ballots exhausting, something that was exceedingly rare under the previous rules. At the 2016 Federal election, there were just over 1 million exhausted votes, about 7.5% of the total. -

Abolition of the Upper House Community Engagement – Updated 27 March 2001

Abolition of the Upper House Community Engagement – Updated 27 March 2001 THE ABOLITION OF THE UPPER HOUSE IN QUEENSLAND INTRODUCTION Unicameral legislatures, or legislatures with only one chamber, are uncommon in democracies. It is usually considered that two chambers are necessary for government, and this is the case for the United Kingdom, Canada (at the Federal level) and the United States (Federally, and for all states except Nebraska.) However, some countries, usually small ones, are unicameral. Israel, Denmark, Finland, Luxembourg, Sweden, and Greece have only one chamber. All the Canadian Provinces, all the Malaysian States and some of the Indian ones, including Assam, are unicameral. Other single-chambered legislatures in the Commonwealth include New Zealand, Ghana, Cyprus, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, Malta, Malawi, Zambia, Gambia, Guyana, Singapore, Botswana, Zimbabwe and (Western) Samoa. In Australia, the Federal Government has two chambers, as do the governments of all the states, except Queensland. At its separation from New South Wales in 1859, Queensland had two houses of Parliament, the Legislative Assembly and the Legislative Council. But in a move unique in Australian history, the Legislative Council abolished itself. EARLY DAYS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL, 1860-1890 Queensland, separated from New South Wales in 1859, was the only colony to have a Parliament from its inception. When the Parliament of Queensland was first promulgated in 1860, there were two houses of Parliament. The first members of the Upper House, the Legislative Council, were appointed for five years by the Governor of New South Wales, so that Queensland would not be left permanently with nominees from the Governor of another colony. -

Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Inquiry Into the Conduct of the 2013 Federal Election

11 April 2014 Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Parliament House Canberra ACT Please find attached my submission to the Committee's inquiry into the conduct of the 2013 federal election. In my submission I make suggestions for changes to political party registration under the Commonwealth Electoral Act. I also suggest major changes to Senate's electoral system given the evident problems at lasty year's election as well as this year's re-run of the Western Australian Senate election. I also make modest suggestions for changes to formality rules for House of Representatives elections. I have attached a substantial appendix outlining past research on NSW Legislative Council Elections. This includes ballot paper surveys from 1999 and research on exhaustion rates under the new above the line optional preferential voting system used since 2003. I can provide the committee with further research on the NSW Legislative Council system, as well as some ballot paper research I have been carrying out on the 2013 Senate election. I am happy to discuss my submission with the Committee at a hearing. Yours, Antony Green Election Analyst Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Inquiry into the Conduct of the 2013 Federal Election Antony Green Contents Page 1. Political Party Registration 1 2. Changes to the Senate's Electoral System 7 2.1 Allow Optional Preferential Voting below the line 8 2.2 Above the Line Optional Preferential Voting 9 2.3 Hare Clark 10 2.4 Hybrid Group Ticket Option 10 2.5 Full Preferential Voting Above the Line 11 2.6 Threshold Quotas 11 2.7 Optional Preferential Voting with a Re-calculating Quota 12 2.8 Changes to Formula 12 2.9 My Suggested Solution 13 3. -

My Wikileaks Party Inquiry

My WikiLeaks Party Inquiry by Gary Lord (@Jaraparilla) A full independent review of what really happened to The Wikileaks Party. “I am not a politician.” - Julian Assange. Table of Contents Mandate................................................................................................................................................2 Terms of Reference...............................................................................................................................2 Objectives.............................................................................................................................................2 Scope....................................................................................................................................................2 Methodology.........................................................................................................................................3 Assumptions.........................................................................................................................................3 Review & Approval..............................................................................................................................3 About the Author..................................................................................................................................4 Historical Background..........................................................................................................................5 Party Foundations............................................................................................................................5 -

Donor to Political Party Return Form

Donor to Political Party Disclosure Return – Individuals FINANCIAL YEAR 2014–15 The due date for lodging this return is 17 November 2015 Completing the Return: • This return is to be completed by a person who made a gift to a registered political party (or a State branch), or to another person or organisation with the intention of benefiting a registered political party. • This return is to be completed with reference to the Financial Disclosure Guide for Donors to Political Parties. • Further information is available at www.aec.gov.au. • This return will be available for public inspection from Monday 1 February 2016 at www.aec.gov.au. • Any supporting documentation included with this return may be treated as part of a public disclosure and displayed on the AEC website. • The information on this return is collected under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. NOTE: This form is for the use of individuals only. Please use the form Political Party Disclosure Return- Organisations if you are completing a return for an organisation. Details of person that made the donation Name Postal address Suburb/Town State Postcode Telephone number ( ) Fax number ( ) Email address Certification I certify that the information contained in this return and its attachments is true and complete to the best of my knowledge information and belief. I understand that giving false or misleading information is a serious offence. Signature Date Enquiries and returns Funding and Disclosure Phone: 02 6271 4552 should be addressed to: Australian Electoral Commission Fax: 02 6293 7655 PO Box 6172 Email: [email protected] Kingston ACT 2604 Office use only Date received DAR_1_indiv. -

Papers on Parliament No. 14

PAPERS ON PARLIAMENT Number 14 February 1992 Parliamentary Perspectives 1991 Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X The Department of the Senate acknowledges the assistance of the Department of the Parliamentary Reporting Staff. Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra NOTE This issue of Papers on Parliament includes lectures given in the Senate Department's Occasional Lecture series during the second half of 1991, together with a paper given by the Clerk of the Senate, Harry Evans, to a seminar organised by the Queensland Electoral and Administrative Review Commission in Brisbane on 26 July 1991. It concludes with a digest of procedurally significant events in the Senate during 1991 which we hope to include as a regular feature of Papers on Parliament. CONTENTS Page Chapter 1 - John Black, Michael Macklin and Chris Puplick 1 How Parliament Works in Practice Chpater 2 - John Button 20 The Role of the Leader of the Government in the Senate Chpater 3 - Hugh Collins 31 Political Literacy: Educating for Democracy Chapter 4 - Harry Evans 47 Parliamentary Reform: New Directions and Possibilities for Reform of Parliamentary Processes Chapter 5 - Senate Department 61 Senate Procedural Digest 1991 Parliamentary Reform: New Directions and Possibilities for Reform of Parliamentary Processes Harry Evans Clerk of the Senate Parliament and the Problem of Government In considering the reform of parliament we are examining the alteration of the basic institutions of government, and it is therefore wise to refer to first principles, and to ponder how the task relates to the elementary problem of government. The great difficulty of government is the creation of authorities with sufficient power to achieve the desired aims of government, peace and order, while preventing the unintended misuse of that power. -

The Caretaker Election

26. The Results and the Pendulum Malcolm Mackerras The two most interesting features of the 2010 election were that it was close and it was an early election. Since early elections are two-a-penny in our system, I shall deal with the closeness of the election first. The early nature of the election does, however, deserve consideration because it was early on two counts. These are considered below. Of our 43 general elections so far, this was the only one both to be close and to be an early election. Table 26.1 Months of General Elections for the Australian House of Representatives, 1901–2010 Month Number Years March 5 1901,1983, 1990, 1993, 1996 April 2 1910, 1951 May 4 1913, 1917, 1954, 1974 July 1 1987 August 2 1943, 2010 September 4 1914, 1934, 1940, 1946 October 6 1929, 1937, 1969, 1980, 1998, 2004 November 7 1925, 1928, 1958, 1963, 1966, 2001, 2007 December 12 1903, 1906, 1919, 1922, 1931, 1949, 1955, 1961, 1972, 1975, 1977, 1984 Total 43 The Close Election In the immediate aftermath of polling day, several commentators described this as the closest election in Australian federal history. While I can see why people would say that, I describe it differently. As far as I am concerned, there have been 43 general elections for our House of Representatives of which four can reasonably be described as having been close. They are the House of Representatives plus half-Senate elections held on 31 May 1913, 21 September 1940, 9 December 1961 and 21 August 2010. -

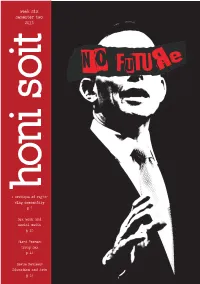

Week Six Semester Two 2013

week six semester two 2013 honi soit honi A critique of right- wing commentary p 7 Sex work and social media p 10 First Person: Group Sex p 12 Revue Reviews: Education and Arts p 16 DISCONTENTS The art of listening COKE IN THE 4 BUBBLERS As easy it is to become apathetic about rience that we may never be unlucky individual threads are loathe to be sev- the current state of Australian politics enough to have scarred onto our bodies ered. The warmest fabrics are built from Hannah Ryan and give up altogether, your vote will and minds, but that we may be trusted the collaboration, peaceful coexistence help lessen the possibility of an Abbott- enough to share. If you are trusted with and reciprocity of the threads that com- MALE POLITICIANS’ led government. Use it wisely. But of them, treat the fragments kindly. Some- prise it. Of we, the threads, that hold course, you’ve heard this all before, so times they flicker with structural oppres- the fragile balance of power in our 8 DAUGHTERS I’ll leave it here. Don’t let him win. sion, institutionalised discrimination, daily weaves, that collectively dictate the Matilda Surtees Now, onto more practical matters. and daily struggle. structural integrity of the fabric. Being wrong can be a useful experi- Ask questions. Considerate, relevant And lessons learnt in fraying threads THE JOB ence. When we are wrong, we learn. questions. Listen for the answers that are not fast forgotten. 11 But only if we listen. Last week, a par- explain better than wilful ignorance, Listen for knowledge and understand- INTERVIEW ticularly saddening Facebook argument bigotry, projected insecurities and the ing, empathise with grief, and ask for Anonymous I was lurking got me thinking. -

JSCEM Submission K Bonham

Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters: Inquiry into and report on all aspects of the conduct of the 2013 Federal Election and matters related thereto. by Dr Kevin Bonham, submitted 10 April 2014 Summary This submission concerns the system for voting in Senate elections. Following the 2013 Australian federal elections, the existing Senate system of group ticket voting is argued to be broken on account of the following problems: * Candidates being elected through methods other than genuine voter intention from very low primary votes. * Election outcomes depending on irrelevant events involving uncompetitive parties early in preference distributions. * The frequent appearance of perverse outcomes in which a party would have been more successful had it at some stage had fewer votes. * Oversized ballot papers, contributing to confusion between similarly-named parties. * Absurd preference deals and strategies, resulting in parties assigning their preferences to parties their supporters would be expected to oppose. * The greatly increased risk of close results that are then more prone to being voided as a result of mistakes by electoral authorities. This submission recommends reform of the Senate system. The main proposed reform recommended is the replacement of Group Ticket Voting with a system in which a voter can choose to: * vote above the line for one or more parties, with preferences distributed to those parties and no other; or * vote below the line with preferences to at least a prescribed minimum number of candidates -

Voting in AUSTRALIAAUSTRALIA Contents

Voting IN AUSTRALIAAUSTRALIA Contents Your vote, your voice 1 Government in Australia: a brief history 2 The federal Parliament 5 Three levels of government in Australia 8 Federal elections 9 Electorates 10 Getting ready to vote 12 Election day 13 Completing a ballot paper 14 Election results 16 Changing the Australian Constitution 20 Active citizenship 22 Your vote, your voice In Australia, citizens have the right and responsibility to choose their representatives in the federal Parliament by voting at elections. The representatives elected to federal Parliament make decisions that affect many aspects of Australian life including tax, marriage, the environment, trade and immigration. This publication explains how Australia’s electoral system works. It will help you understand Australia’s system of government, and the important role you play in it. This information is provided by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), an independent statutory authority. The AEC provides Australians with an independent electoral service and educational resources to assist citizens to understand and participate in the electoral process. 1 Government in Australia: a brief history For tens of thousands of years, the heart of governance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was in their culture. While traditional systems of laws, customs, rules and codes of conduct have changed over time, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to share many common cultural values and traditions to organise themselves and connect with each other. Despite their great diversity, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities value connection to ‘Country’. This includes spirituality, ceremony, art and dance, family connections, kin relationships, mutual responsibility, sharing resources, respecting law and the authority of elders, and, in particular, the role of Traditional Owners in making decisions.