Hambledon Hill - an Overview of Its Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

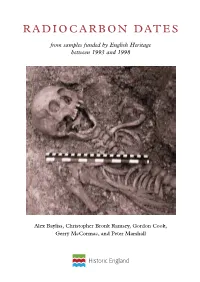

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

Settlement Hierarchy and Social Change in Southern Britain in the Iron Age

SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN IN THE IRON AGE BARRY CUNLIFFE The paper explores aspects of the social and economie development of southern Britain in the pre-Roman Iron Age. A distinct territoriality can be recognized in some areas extending over many centuries. A major distinction can be made between the Central Southern area, dominated by strongly defended hillforts, and the Eastern area where hillforts are rare. It is argued that these contrasts, which reflect differences in socio-economic structure, may have been caused by population pressures in the centre south. Contrasts with north western Europe are noted and reference is made to further changes caused by the advance of Rome. Introduction North western zone The last two decades has seen an intensification Northern zone in the study of the Iron Age in southern Britain. South western zone Until the early 1960s most excavation effort had been focussed on the chaiklands of Wessex, but Central southern zone recent programmes of fieid-wori< and excava Eastern zone tion in the South Midlands (in particuiar Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire) and in East Angiia (the Fen margin and Essex) have begun to redress the Wessex-centred balance of our discussions while at the same time emphasizing the social and economie difference between eastern England (broadly the tcrritory depen- dent upon the rivers tlowing into the southern part of the North Sea) and the central southern are which surrounds it (i.e. Wessex, the Cots- wolds and the Welsh Borderland. It is upon these two broad regions that our discussions below wil! be centred. -

Changing Identities in a Changing Land: the Romanization of the British Landscape

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Changing Identities in a Changing Land: The Romanization of the British Landscape Thomas Ryan Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/617 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Changing Identities in a Changing Land: The Romanization of the British Landscape By Thomas J. Ryan Jr. A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2015 Thomas J. Ryan Jr. All Rights Reserved. 2015 ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis _______________ ______________________________ Date Thesis Advisor Matthew K. Gold _______________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract CHANGING IDENTITIES IN A CHANGING LAND: THE ROMANIZATION OF THE BRITISH LANDSCAPE By Thomas J. Ryan Jr. Advisor: Professor Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis This thesis will examine the changes in the landscape of Britain resulting from the Roman invasion in 43 CE and their effect on the identities of the native Britons. Romanization, as the process is commonly called, and evidence of these altered identities as seen in material culture have been well studied. -

Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the Nearer Continent

Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the Nearer Continent Papers from the Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland Conference, June 2017 edited by Gary Lock and Ian Ralston Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-226-6 ISBN 978-1-78969-227-3 (e-Pdf) © Authors and Archaeopress 2019 Cover images: A selection of British and Irish hillforts. Four-digit numbers refer to their online Atlas designations (Lock and Ralston 2017), where further information is available. Front, from top: White Caterthun, Angus [SC 3087]; Titterstone Clee, Shropshire [EN 0091]; Garn Fawr, Pembrokeshire [WA 1988]; Brusselstown Ring, Co Wicklow [IR 0718]; Back, from top: Dun Nosebridge, Islay, Argyll [SC 2153]; Badbury Rings, Dorset [EN 3580]; Caer Drewyn Denbighshire [WA 1179]; Caherconree, Co Kerry [IR 0664]. Bottom front and back: Cronk Sumark [IOM 3220]. Credits: 1179 courtesy Ian Brown; 0664 courtesy James O’Driscoll; remainder Ian Ralston. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Severn, Gloucester This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of Figures ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ii -

Mourning the Sacrifice Behavior and Meaning Behind Animal Burials

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK Mourning the Sacrifice Behavior and Meaning behind Animal Burials JAMES MORRIS The remains of animals, fragments of bone and horn, are often the most common finds recovered from archaeological excavations. The potential of using this mate- rial to examine questions of past economics and environment has long been recognized and is viewed by many archaeologists as the primary purpose of animal remains. In part this is due to the paradigm in which zooarchaeology developed and a consequence of prac- titioners’ concentration on taphonomy and quantification.1 But the complex intertwined relationships between humans and animals have long been recognized, a good example being Lévi-Strauss’s oft quoted “natural species are chosen, not because they are ‘good to eat’ but because they are ‘good to think.’”2 The relatively recent development of social zooarchae- ology has led to a more considered approach to the meanings and relationships animals have with past human cultures.3 Animal burials are a deposit type for which social, rather than economic, interpretations are of particular relevance. When animal remains are recovered from archaeological sites they are normally found in a state of disarticulation and fragmentation, but occasionally remains of an individual animal are found in articulation. These types of deposits have long been noted in the archaeological record, although their descriptions, such as “special animal deposit,”4 can be heavily loaded with interpretation. In Europe some of the earliest work on animal buri- als was Behrens’s investigation into the “Animal skeleton finds of the Neolithic and Early Metallic Age,” which discussed 459 animal burials from across Europe.5 Dogs were the most common species to be buried, and the majority of these cases were associated with inhumations. -

The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles

www.RodnoVery.ru www.RodnoVery.ru The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles www.RodnoVery.ru Callanish Stone Circle Reproduced by kind permission of Fay Godwin www.RodnoVery.ru The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles Their Nature and Legacy RONALD HUTTON BLACKWELL Oxford UK & Cambridge USA www.RodnoVery.ru Copyright © R. B. Hutton, 1991, 1993 First published 1991 First published in paperback 1993 Reprinted 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998 Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford 0X4 1JF, UK Blackwell Publishers Inc. 350 Main Street Maiden, Massachusetts 02148, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Hutton, Ronald The pagan religions of the ancient British Isles: their nature and legacy / Ronald Hutton p. cm. ISBN 0-631-18946-7 (pbk) 1. -

Hambledon Hill National Nature Reserve Man’S Influence on Hambledon Hill Has Been Hambledon Hill Profound, but Spread Across Thousands of Years

Hambledon Hill National Nature Reserve Man’s influence on Hambledon Hill has been Hambledon Hill profound, but spread across thousands of years. The ancient forests that at one time covered most National Nature Reserve of lowland Britain were probably cleared from Hambledon Hill is an exceptional place for wildlife around Hambledon when Neolithic people settled and archaeology. The Reserve covers 74 hectares there more than 5000 years ago. and lies four miles north-west of Blandford between the Stour and Iwerne valleys. Rising to 192 The open grassland developed as successive metres above sea level it affords superb views over civilizations cleared the trees and grazed their the surrounding countryside. livestock. The earthworks, perhaps the biggest influence on the hill, have added many steeper Only a few fragments of Dorset’s once common slopes which favour Hambledon’s special wildlife. chalk grassland remain. Hambledon’s extensive Most of the grassland remains untouched by grassland with its variety of slope and aspect fertilisers or herbicides. provide the nature conservation interest for which Hambledon Hill was declared a National Nature Reserve. The archaeological remains are of international importance and are protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument. The grasslands The thin chalky soils on the steep rampart slopes 1. Quaking grass 2. Salad burnet are dry and infertile; ideal conditions for fine 3. Horseshoe vetch grasses, sedges and an astonishing variety of 4. Wild thyme flowering plants. The gullies between the ramparts 5. Chalk milkwort are dominated by vigorous grasses and plants 6. Mouse-ear hawkweed such as nettles because the soil is deeper and more fertile. -

2. a History of Dorset Hillfort Investigation

2. A HISTORY OF DORSET HILLFORT INVESTIGATION John Gale Most of Dorset’s hillforts are to be found on the chalk downlands of the county but others are found on the limestone of Purbeck and in the clay vales to the extreme west of Dorset as well as those on the gravels of Poole basin. Of the 34 sites identified, more than a third have been the subject of some form of excavation but only four of these (Chalbury, Hod Hill, Maiden Castle and Pilsden Pen) could claim to have been significantly sampled. The problem is not that the sites are especially difficult to excavate but rather it is a question of scale. To understand such complex earthworks it would be preferable to excavate them completely but, generally speaking, large scale sampling should be sufficient. With hillforts, of course, the question is how large is large? This is a matter that can only be defined on a case by case basis, but certainly it is likely to be greater than 25% of the whole. Unfortunately, only two hillforts in England and Wales have achieved such attention: Crickley Hill in Gloucestershire (Dixon 1996) and Danebury in Hampshire (Cunliffe 1984), each with more than 50% of their interiors excavated. The most closely and extensively studied of the Dorset hillforts is Maiden Castle, which has been the subject of two major excavation campaigns, Tessa and Mortimer Wheeler in the 1930s (Wheeler 1943) and Niall Shaples in the mid-1980s (Sharples 1991). Neither of these excavations sampled more than a fraction of the enclosed area, in both cases no more than 1%, but the recovered evidence presents a detailed picture of life within the hillfort spanning almost the whole of the Iron Age. -

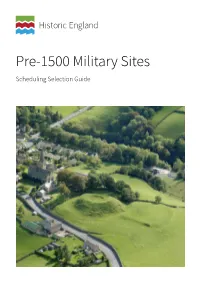

Pre-1500 Military Sites Scheduling Selection Guide Summary

Pre-1500 Military Sites Scheduling Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s scheduling selection guides help to define which archaeological sites are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. For archaeological sites and monuments, they are divided into categories ranging from Agriculture to Utilities and complement the listing selection guides for buildings. Scheduling is applied only to sites of national importance, and even then only if it is the best means of protection. Only deliberately created structures, features and remains can be scheduled. The scheduling selection guides are supplemented by the Introductions to Heritage Assets which provide more detailed considerations of specific archaeological sites and monuments. This selection guide offers an overview of archaeological monuments or sites designed to have a military function and likely to be deemed to have national importance, and sets out criteria to establish for which of those scheduling may be appropriate. The guide aims to do two things: to set these sites within their historical context, and to give an introduction to some of the overarching and more specific designation considerations. This document has been prepared by Listing Group. It is one is of a series of 18 documents. This edition published by Historic England July 2018. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Please refer to this document as: Historic England 2018 Pre-1500 Military Sites: Scheduling Selection Guide. Swindon. Historic England. HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/selection-criteria/scheduling-selection/ Front cover The castle at Burton-in-Lonsdale, North Yorkshire was built around 1100 as a ringwork; later it was reconstructed as a motte with two baileys. -

WESSEX Ridgeway

The WESSEX Ridgeway Official guide to this long-distance walking, horse riding and cycling trail across Dorset’s rural heartland Key to section maps WESSEX RIDGEWAY TRAIL Wessex Ridgeway (walking, horse riding & cycling) Wessex Ridgeway (walking only) 2 Place of interest TOURIST AND LEISURE INFORMATION Tourist Information Centre Public convenience Parking (walking, horse riding & cycling) Parking (walking and cycling only) Other recreational trail Archaeological feature WILDLIFE AND RECREATION SITES Please keep to dedicated paths Dorset Wildlife Trust Forestry Commission National Nature Reserve National Trust ROADS RAILWAYS Trunk or Main road Railway line Minor road Train station FEATURES River Woodland Farm, Village or Town area SCALE 1cm = 0.537 km Miles Welcome to the Wessex Ridgeway to the Wessex Welcome 01 2 0 123 Kilometres 02 ALSO AVAILABLE Wildlife of the Wessex Ridgeway (leaflet) Local History along the Wessex Ridgeway (leaflet) Wessex Ridgeway, Dorset (leaflet) North Dorset Cycling Pack Picture Trek – Countryside Activity Trails (leaflet) The Wessex Ridgeway – An Audio Journey to the Sea (CD ROM) Free to download at www.dorsetforyou.com/wessexridgeway Welcome to the Wessex Ridgeway to the Wessex Welcome Cranborne Chase 03 Acknowledgements Thanks to the late Priscilla Houstoun of the Ramblers’ Association who set up the walking route in the 1980s. Thank you to members of the British Horse Society, Ramblers’ Association and all the landowners whose help and support made this multi-use trail possible. The trail has been developed and is managed by Dorset Countryside, Dorset County Council’s Countryside Ranger Service with funding from the EU Leader+ ‘Dorset Chalk and Cheese’ Programme, Dorset AONB, Liveability and the Environment Agency. -

Hillforts and the Durotriges a Geophysical Survey of Iron Age Dorset

Hillforts and the Durotriges A geophysical survey of Iron Age Dorset Dave Stewart Miles Russell With contributions by Paul Cheetham and John Gale Illustrations by Justin Russell Aerial photographs by Jo and Sue Crane Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 715 9 ISBN 978 1 78491 716 6 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2017 Cover: Flowers Barrow hillfort looking south-east to the English Channel (Jo and Sue Crane) Durotrigian silver stater: obverse and reverse (Miles Russell) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of Figures ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii 1� Introduction: The Durotriges Project ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Miles Russell and Paul Cheetham 2� Defining Hillforts in Dorset �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Dave Stewart and Miles Russell 3� A History of Dorset Hillfort Investigation ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������13 -

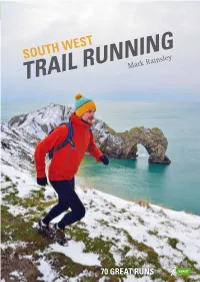

Trail Running

SOUTH WEST SOUTH WEST SOUTH WEST TRAIL RUNNING Mark Rainsley 70 routes for the off-road runner: these tried and tested TRAIL RUNNING paths and tracks cover the south-west of England, including the Isles of Scilly. Trail running is a great way to explore the South West and to immerse TRAIL yourself in its incredible landscapes. This guide is intended to inspire runners of all abilities to develop the skills and confidence to seek out new trails in their local areas as well as further afield. They are all great runs; selected for their runnability, landscape and scenery. The selection is deliberately diverse and is chosen to highlight the R incredible range of trail running adventures that the South West can UNNING offer. The runs are graded to help progressive development of the skills and confidence needed to tackle more challenging routes. TRAIL RUNNING FOR EVERYONE CLOSE TO TOWN & FAR AFIELD. Mark Rainsley ISBN 9781906095673 9 781906 095673 Front cover – Durdle Door Back cover – Porthcothan Bay www.pesdapress.com 70 GREAT RUNS h g old ou essex r W 65 wood W 64 g Downs the- Stow-on- Salisbury Swindon Rin North Marlbo 59 encester 63 The Bournemouth r 62 Plain 67 Ci Cotswolds 58 Salisbury ne 53 d 61 r r 52 Cheltenham 70 Distance Ascent Route Route Distance Ascent Route Route Poole Chase 51 Page Page WILTSHIRE 57 Cranbo 55 Forum (km) (m) No. Name Chippenham (km) (m) No. Name arminster 56 Blandfo 50 W 69 5.5 100 56 The Wardour Castles 265 13 425 48 Durdle Door 231 60 49 68 7 150 70 Cleeve Hill 325 48 13 425 51 St Alban’s Head 243 54 chester