2. a History of Dorset Hillfort Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Northgate Reconstruction

131 7 THE NORTHGATE RECONSTRUCTION P Holder and J Walker INTRODUCTION have come from the supposedly ancient quarries at Collyhurst some few kilometres north-east of the The Unit was asked to provide advice and fort. As this source was not available, Hollington assistance to Manchester City Council so that the Red Sandstone from Staffordshire was used to form City could reconstruct the Roman fort wall and a wall of coursed facing blocks 200-320 mm long by defences at Manchester as they would have appeared 140-250 mm deep by 100-120 mm thick. York stone around the beginning of the 3rd century (Phase 4). was used for paving, steps and copings. A recipe for the right type of mortar, which consisted of This short report has been included in the volume three parts river sand, three parts building sand, in order that a record of the archaeological work two parts lime and one part white cement, was should be available for visitors to the site. obtained from Hampshire County Council. The Ditches and Roods The Wall and Rampart The Phase 4a (see Chapter 4, Area B) ditches were Only the foundations and part of the first course re-establised along their original line to form a of the wall survived (see Chapter 4, Phase 4, Area defensive circuit consisting of an outer V-shaped A). The underlying foundations consisted of ditch in front of a smaller inner ditch running interleaved layers of rammed clay and river close to the fort wall. cobble. On top of the foundations of the fort wall lay traces of a chamfered plinth (see Chapter 5g) There were three original roads; the main road made up of large red sandstone blocks, behind from the Northgate that ran up to Deansgate, the which was a rough rubble backing. -

Hooke Court, Hooke, Dorset

Wessex Archaeology Hooke Court, Hooke, Dorset Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of the Results Ref: 62502.01 December 2006 Hooke Court, Hooke, Dorset Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON W12 8QP By Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 62502.01 December 2006 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2006, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Hooke Court, Hooke, Dorset Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................1 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology..................................................1 1.3 Historical Background...............................................................................1 Hooke Court.................................................................................................1 The Village of Stapleford .............................................................................3 1.4 Previous Archaeological Work .................................................................3 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES.................................................................................4 3 METHODS...........................................................................................................5 -

The Antonine Wall, the Roman Frontier in Scotland, Was the Most and Northerly Frontier of the Roman Empire for a Generation from AD 142

Breeze The Antonine Wall, the Roman frontier in Scotland, was the most and northerly frontier of the Roman Empire for a generation from AD 142. Hanson It is a World Heritage Site and Scotland’s largest ancient monument. The Antonine Wall Today, it cuts across the densely populated central belt between Forth (eds) and Clyde. In The Antonine Wall: Papers in Honour of Professor Lawrence Keppie, Papers in honour of nearly 40 archaeologists, historians and heritage managers present their researches on the Antonine Wall in recognition of the work Professor Lawrence Keppie of Lawrence Keppie, formerly Professor of Roman History and Wall Antonine The Archaeology at the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow University, who spent edited by much of his academic career recording and studying the Wall. The 32 papers cover a wide variety of aspects, embracing the environmental and prehistoric background to the Wall, its structure, planning and David J. Breeze and William S. Hanson construction, military deployment on its line, associated artefacts and inscriptions, the logistics of its supply, as well as new insights into the study of its history. Due attention is paid to the people of the Wall, not just the ofcers and soldiers, but their womenfolk and children. Important aspects of the book are new developments in the recording, interpretation and presentation of the Antonine Wall to today’s visitors. Considerable use is also made of modern scientifc techniques, from pollen, soil and spectrographic analysis to geophysical survey and airborne laser scanning. In short, the papers embody present- day cutting edge research on, and summarise the most up-to-date understanding of, Rome’s shortest-lived frontier. -

The Iron Age Tom Moore

The Iron Age Tom Moore INTRODUCfiON In the twenty years since Alan Saville's (1984) review of the Iron Age in Gloucestershire much has happened in Iron-Age archaeology, both in the region and beyond.1 Saville's paper marked an important point in Iron-Age studies in Gloucestershire and was matched by an increasing level of research both regionally and nationally. The mid 1980s saw a number of discussions of the Iron Age in the county, including those by Cunliffe (1984b) and Darvill (1987), whilst reviews were conducted for Avon (Burrow 1987) and Somerset (Cunliffe 1982). At the same time significant advances and developments in British Iron-Age studies as a whole had a direct impact on how the period was viewed in the region. Richard Hingley's (1984) examination of the Iron-Age landscapes of Oxfordshire suggested a division between more integrated unenclosed communities in the Upper Thames Valley and isolated enclosure communities on the Cotswold uplands, arguing for very different social systems in the two areas. In contrast, Barry Cunliffe' s model ( 1984a; 1991 ), based on his work at Danebury, Hampshire, suggested a hierarchical Iron-Age society centred on hillforts directly influencing how hillforts and social organisation in the Cotswolds have been understood (Darvill1987; Saville 1984). Together these studies have set the agenda for how the 1st millennium BC in the region is regarded and their influence can be felt in more recent syntheses (e.g. Clarke 1993). Since 1984, however, our perception of Iron-Age societies has been radically altered. In particular, the role of hillforts as central places at the top of a hierarchical settlement pattern has been substantially challenged (Hill 1996). -

The Early Medieval Period, Its Main Conclusion Is They Were Compiled at Malmesbury

Early Medieval 10 Early Medieval Edited by Chris Webster from contributions by Mick Aston, Bruce Eagles, David Evans, Keith Gardner, Moira and Brian Gittos, Teresa Hall, Bill Horner, Susan Pearce, Sam Turner, Howard Williams and Barbara Yorke 10.1 Introduction raphy, as two entities: one “British” (covering most 10.1.1 Early Medieval Studies of the region in the 5th century, and only Cornwall by the end of the period), and one “Anglo-Saxon” The South West of England, and in particular the three (focusing on the Old Sarum/Salisbury area from the western counties of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset, later 5th century and covering much of the region has a long history of study of the Early Medieval by the 7th and 8th centuries). This is important, not period. This has concentrated on the perceived “gap” only because it has influenced past research questions, between the end of the Roman period and the influ- but also because this ethnic division does describe (if ence of Anglo-Saxon culture; a gap of several hundred not explain) a genuine distinction in the archaeological years in the west of the region. There has been less evidence in the earlier part of the period. Conse- emphasis on the eastern parts of the region, perhaps quently, research questions have to deal less with as they are seen as peripheral to Anglo-Saxon studies a period, than with a highly complex sequence of focused on the east of England. The region identi- different types of Early Medieval archaeology, shifting fied as the kingdom of Dumnonia has received detailed both chronologically and geographically in which issues treatment in most recent work on the subject, for of continuity and change from the Roman period, and example Pearce (1978; 2004), KR Dark (1994) and the evolution of medieval society and landscape, frame Somerset has been covered by Costen (1992) with an internally dynamic period. -

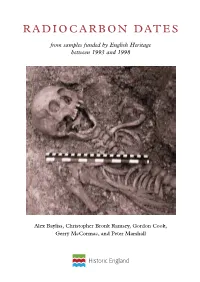

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

Settlement Hierarchy and Social Change in Southern Britain in the Iron Age

SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN IN THE IRON AGE BARRY CUNLIFFE The paper explores aspects of the social and economie development of southern Britain in the pre-Roman Iron Age. A distinct territoriality can be recognized in some areas extending over many centuries. A major distinction can be made between the Central Southern area, dominated by strongly defended hillforts, and the Eastern area where hillforts are rare. It is argued that these contrasts, which reflect differences in socio-economic structure, may have been caused by population pressures in the centre south. Contrasts with north western Europe are noted and reference is made to further changes caused by the advance of Rome. Introduction North western zone The last two decades has seen an intensification Northern zone in the study of the Iron Age in southern Britain. South western zone Until the early 1960s most excavation effort had been focussed on the chaiklands of Wessex, but Central southern zone recent programmes of fieid-wori< and excava Eastern zone tion in the South Midlands (in particuiar Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire) and in East Angiia (the Fen margin and Essex) have begun to redress the Wessex-centred balance of our discussions while at the same time emphasizing the social and economie difference between eastern England (broadly the tcrritory depen- dent upon the rivers tlowing into the southern part of the North Sea) and the central southern are which surrounds it (i.e. Wessex, the Cots- wolds and the Welsh Borderland. It is upon these two broad regions that our discussions below wil! be centred. -

Signalling and Beacon Sites in Dorset

THE DORSET DIGGER THE NEWSLETTER OF THE DORSET DIGGERS COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY GROUP No 43 December 2016 Signalling and Beacon Sites in Dorset Richard Hood has kicked off this new project. He needs somemorevolunteerstohelpwith the research Introduction The ability to send or receive a message over a distance to warn of impending attack has been used to mobilise troops for defence since the Roman times. The Romans developed a system using five flags or torches to carry a simple message over short distances. This was usually used in battle to pass information out to army commanders. To carry a simple message further, a bonfire was used set on a high point, usually from a mini fort within vision of one or more other sites. This type of warning system was used during the invasion of Britain, when vexation forts could come under attack from tribes yet to be persuaded of the advantages of Roman living. Near the end of the Roman occupation signal stations were employed on the East and South coasts to warn of Saxon pirates. Roman signal stations on the NE coast of England took the form of mini forts, with a ditch and bank for defence. Black Down in Dorset, excavated by Bill Putnam and re examined by Dorset Diggers in 2016 is of this type. The Saxons appear to have had a system of inter divisible beacon sites to warn of Viking attack from the ninth century onwards. Later, beacons were erected to warn of the approach of the Spanish Armada, followed by a similar, but unused system, to warn of Napoleonic invasion. -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

Old Oswestry Hillfort and Its Landscape: Ancient Past, Uncertain Future

Old Oswestry Hillfort and its Landscape: Ancient Past, Uncertain Future edited by Tim Malim and George Nash Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-611-0 ISBN 978-1-78969-612-7 (e-Pdf) © the individual authors and Archaeopress 2020 Cover: Painting of Old Oswestry Hillfort by Allanah Piesse Back cover: Old Oswestry from the air, photograph by Alastair Reid Please note that all uncredited images and photographs within each chapter have been produced by the individual authors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Contributors ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ii Preface: Old Oswestry – 80 years on �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������v Tim Malim and George Nash Part 1 Setting the scene Chapter 1 The prehistoric Marches – warfare or continuity? �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 David J. Matthews Chapter 2 Everybody needs good neighbours: Old Oswestry hillfort in context ��������������������������������������������� -

Winchester Museums Service Historic Resources Centre

GB 1869 AA2/110 Winchester Museums Service Historic Resources Centre This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 41727 The National Archives ppl-6 of the following report is a list of the archaeological sites in Hampshire which John Peere Williams-Freeman helped to excavate. There are notes, correspondence and plans relating to each site. p7 summarises Williams-Freeman's other papers held by the Winchester Museums Service. William Freeman Index of Archaeology in Hampshire. Abbots Ann, Roman Villa, Hampshire 23 SW Aldershot, Earthwork - Bats Hogsty, Hampshire 20 SE Aldershot, Iron Age Hill Fort - Ceasar's Camp, Hampshire 20 SE Alton, Underground Passage' - Theddon Grange, Hampshire 35 NW Alverstoke, Mound Cemetery etc, Hampshire 83 SW Ampfield, Misc finds, Hampshire 49 SW Ampress,Promy fort, Hampshire 80 SW Andover, Iron Age Hill Fort - Bagsbury or Balksbury, Hampshire 23 SE Andover, Skeleton, Hampshire 24 NW Andover, Dug-out canoe or trough, Hampshire 22 NE Appleshaw, Flint implement from gravel pit, Hampshire 15 SW Ashley, Ring-motte and Castle, Hampshire 40 SW Ashley, Earthwork, Roman Building etc, Hampshire 40 SW Avington, Cross-dyke and 'Ring' - Chesford Head, Hampshire 50 NE Barton Stacey, Linear Earthwork - The Andyke, Hampshire 24 SE Basing, Park Pale - Pyotts Hill, Hampshire 19 SW Basing, Motte and Bailey - Oliver's Battery, Hampshire 19 NW Bitterne (Clausentum), Roman site, Hampshire 65 NE Basing, Motte and Bailey, Hampshire 19 NW Basingstoke, Iron -

Landscape Type: Chalk Ridge/Escarpment Backdrops To, and Give Views Of, Much of the Surrounding AONB

The North, West and South Escarpments and the Purbeck Ridge form dramatic Landscape type: Chalk Ridge/Escarpment backdrops to, and give views of, much of the surrounding AONB. Although in geological Character areas: Purbeck Ridge terms an escarpment is slightly different to a ridge, they have been grouped • together for this assessment as they share very similar characteristics and management North Dorset Escarpment requirements. With an undeveloped and open character, this landscape type • with its steep sides, supports important patches of chalk grasslands and hanging • South Dorset Escarpment woodlands. These dramatic landscapes have been captured by the romantic paintings • West Dorset Escarpment and writings of Wilsdon Steer, Moffat Linder, Daniel Defoe and Lamora Birch. Landscape change Planning guidelines • Policy driven farming changes over the last sixty years have resulted in • Maintain the undeveloped character of the scarp and the contrast with the concentration of stock levels. This has limited the availability of livestock to ridge base farmsteads. Any new development should be small scale and should graze land of low agricultural value along the scarp face. In places, this has respect the distinct nucleated form along the surrounding edges of the area and resulted in low grazing pressure and increased scrub encroachment on the should not extend onto the lower slopes. Encourage the use of native species steeper slopes. along property boundaries. • Some historical loss of chalk grassland as a result of intensive arable agricultural • Conserve the rural character of the narrow sunken and open lanes and protect practices have fragmented grassland habitats with issues of soil erosion. sensitive banks from further erosion.