Harding Hillforts Lang Review Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

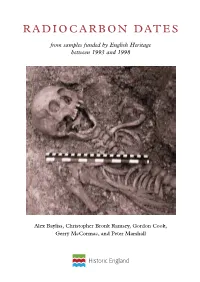

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

Settlement Hierarchy and Social Change in Southern Britain in the Iron Age

SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN IN THE IRON AGE BARRY CUNLIFFE The paper explores aspects of the social and economie development of southern Britain in the pre-Roman Iron Age. A distinct territoriality can be recognized in some areas extending over many centuries. A major distinction can be made between the Central Southern area, dominated by strongly defended hillforts, and the Eastern area where hillforts are rare. It is argued that these contrasts, which reflect differences in socio-economic structure, may have been caused by population pressures in the centre south. Contrasts with north western Europe are noted and reference is made to further changes caused by the advance of Rome. Introduction North western zone The last two decades has seen an intensification Northern zone in the study of the Iron Age in southern Britain. South western zone Until the early 1960s most excavation effort had been focussed on the chaiklands of Wessex, but Central southern zone recent programmes of fieid-wori< and excava Eastern zone tion in the South Midlands (in particuiar Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire) and in East Angiia (the Fen margin and Essex) have begun to redress the Wessex-centred balance of our discussions while at the same time emphasizing the social and economie difference between eastern England (broadly the tcrritory depen- dent upon the rivers tlowing into the southern part of the North Sea) and the central southern are which surrounds it (i.e. Wessex, the Cots- wolds and the Welsh Borderland. It is upon these two broad regions that our discussions below wil! be centred. -

Character Appraisal

Main Heading Aston Tirrold & Aston Upthorpe Conservation Area Character Appraisal The conservation area character appraisal - this sets the context for the proposals contained in Part 2. Part 1 was adopted by Council in September and is included for information only. May 2005 Aston Tirrold and Aston Upthorpe Conservation Area Character Appraisal The Council first published the Aston Tirrold and Aston Upthorpe Conservation Area Character Appraisal in draft form in July 2004. Following th a period of public consultation, including a public meeting held on 12 nd August 2004, the Council approved the Character Appraisal on the 2 September 2004. Contents Introduction . .1 1 Aston Tirrold and Aston Upthorpe The history of the area . .3 Introduction . .3 Aston Tirrold . .3 Aston Upthorpe . .5 Aston Tirrold and Upthorpe from the nineteenth century . .6 2 The established character . .7 Chalk Hill . .9 Aston Street . .9 Baker Street . .12 Spring Lane . .14 The Croft . .16 Fullers Road . .16 Thorpe Street . .19 Important open spaces outside the conservation area . .21 3 Possible areas for enhancement and design guidance for new development . .22 Introduction . .22 The need for contextual design . .22 Grain of the village . .22 Appearance, materials and detailing . .22 Boundary treatments . .23 Scale . .24 Extensions to existing buildings . .24 Repairs . .24 Negative elements . .24 Services . .24 Street furniture . .25 4 South Oxfordshire Local Plan adopted by Council, April 1997 . .26 5 Summary of the conservation policies contained within the 2011 Second Deposit Draft local Plan . .28 6 Acknowledgements and bibliography . .31 ASTON TIRROLD & ASTON UPTHORPE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL i South Oxfordshire District Council ii ASTON TIRROLD & ASTON UPTHORPE CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL South Oxfordshire District Council Part 1 Introduction 2. -

Iron Age Scotland: Scarf Panel Report

Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Images ©as noted in the text ScARF Summary Iron Age Panel Document September 2012 Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Summary Iron Age Panel Report Fraser Hunter & Martin Carruthers (editors) With panel member contributions from Derek Alexander, Dave Cowley, Julia Cussans, Mairi Davies, Andrew Dunwell, Martin Goldberg, Strat Halliday, and Tessa Poller For contributions, images, feedback, critical comment and participation at workshops: Ian Armit, Julie Bond, David Breeze, Lindsey Büster, Ewan Campbell, Graeme Cavers, Anne Clarke, David Clarke, Murray Cook, Gemma Cruickshanks, John Cruse, Steve Dockrill, Jane Downes, Noel Fojut, Simon Gilmour, Dawn Gooney, Mark Hall, Dennis Harding, John Lawson, Stephanie Leith, Euan MacKie, Rod McCullagh, Dawn McLaren, Ann MacSween, Roger Mercer, Paul Murtagh, Brendan O’Connor, Rachel Pope, Rachel Reader, Tanja Romankiewicz, Daniel Sahlen, Niall Sharples, Gary Stratton, Richard Tipping, and Val Turner ii Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Executive Summary Why research Iron Age Scotland? The Scottish Iron Age provides rich data of international quality to link into broader, European-wide research questions, such as that from wetlands and the well-preserved and deeply-stratified settlement sites of the Atlantic zone, from crannog sites and from burnt-down buildings. The nature of domestic architecture, the movement of people and resources, the spread of ideas and the impact of Rome are examples of topics that can be explored using Scottish evidence. The period is therefore important for understanding later prehistoric society, both in Scotland and across Europe. There is a long tradition of research on which to build, stretching back to antiquarian work, which represents a considerable archival resource. -

Historic Landscape Character Areas and Their Special Qualities and Features of Significance

Historic Landscape Character Areas and their special qualities and features of significance Volume 1 Third Edition March 2016 Wyvern Heritage and Landscape Consultancy Emma Rouse, Wyvern Heritage and Landscape Consultancy www.wyvernheritage.co.uk – [email protected] – 01747 870810 March 2016 – Third Edition Summary The North Wessex Downs AONB is one of the most attractive and fascinating landscapes of England and Wales. Its beauty is the result of many centuries of human influence on the countryside and the daily interaction of people with nature. The history of these outstanding landscapes is fundamental to its present‐day appearance and to the importance which society accords it. If these essential qualities are to be retained in the future, as the countryside continues to evolve, it is vital that the heritage of the AONB is understood and valued by those charged with its care and management, and is enjoyed and celebrated by local communities. The North Wessex Downs is an ancient landscape. The archaeology is immensely rich, with many of its monuments ranking among the most impressive in Europe. However, the past is etched in every facet of the landscape – in the fields and woods, tracks and lanes, villages and hamlets – and plays a major part in defining its present‐day character. Despite the importance of individual archaeological and historic sites, the complex story of the North Wessex Downs cannot be fully appreciated without a complementary awareness of the character of the wider historic landscape, its time depth and settlement evolution. This wider character can be broken down into its constituent parts. -

Yeavering Bell « « Coldstream Berwick MILFIELD R Till Ip Site of R Glen Gefrin P B6351 Kirknewton Yeavering Bell

How to reach Yeavering Bell « « Coldstream Berwick MILFIELD R Till ip Site of R Glen Gefrin P B6351 Kirknewton Yeavering Bell B6349 B6526 « Akeld Belford Yeavering and A1 The Hill of the Goats Bell WOOLER B6348 Humbleton A697 in Northumberland National Park Hill © Crown Copyright 2010. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence Number 100022521. Please park at the Gefrin monument lay-by or on the grass verge indicated on the route map. Park carefully and do not block any gates. Please use an Ordnance Survey map: OS Explorer OL 16 The Cheviot Hills. Allow at least 3 hours to complete this 3.5 mile (5.5km) walk. Some of the walking is strenuous, with a steep descent, and the top is very exposed in poor weather. Wear good walking boots and take warm water- proof clothing with you. Nearest National Park Centres: National Park Centre, Rothbury T: +44 (0)1669 620887 National Park Centre, Ingram T: +44 (0)1665 578890 For public transport information: The hillfort is a protected monument and is managed under the terms of an agreement between Northumberland National Park Authority and the landowner. Under the terms of the agreement, parts of the trail may be closed for a few days each year. Contact +44 (0)1434 605555 for closure information. Please respect this ancient site and leave the stones as you find them. To protect wildlife and farm animals, please keep your dog on a lead at all times. Thank you. Supported by Part financed by the June 2010 EUROPEAN AGRICULTURAL A journey through the mists of time to GUIDANCE AND GUARANTEE FUND Northumberland’s most spectacular Iron Age Hillfort Northumberland National Park Authority, Eastburn, South Park, Hexham, Northumberland NE46 1BS Front cover photograph - View from Yeavering Bell © Graeme Peacock. -

Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the Nearer Continent

Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the Nearer Continent Papers from the Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland Conference, June 2017 edited by Gary Lock and Ian Ralston Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-226-6 ISBN 978-1-78969-227-3 (e-Pdf) © Authors and Archaeopress 2019 Cover images: A selection of British and Irish hillforts. Four-digit numbers refer to their online Atlas designations (Lock and Ralston 2017), where further information is available. Front, from top: White Caterthun, Angus [SC 3087]; Titterstone Clee, Shropshire [EN 0091]; Garn Fawr, Pembrokeshire [WA 1988]; Brusselstown Ring, Co Wicklow [IR 0718]; Back, from top: Dun Nosebridge, Islay, Argyll [SC 2153]; Badbury Rings, Dorset [EN 3580]; Caer Drewyn Denbighshire [WA 1179]; Caherconree, Co Kerry [IR 0664]. Bottom front and back: Cronk Sumark [IOM 3220]. Credits: 1179 courtesy Ian Brown; 0664 courtesy James O’Driscoll; remainder Ian Ralston. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Severn, Gloucester This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of Figures ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ii -

Yeavering: a Palace in Its Landscape Research Agenda 2020

Yeavering: A Palace in its Landscape Research Agenda 2020 S. Semple and A. T. Skinner with B. Buchanan Acknowledgements This document has benefitted from initial comments from the following specialists: Peter Carne, Lee McFarlane, Chris Gerrard, Joanne Kirton, Don O’Meara, Andrew Millard, David Petts and Graeme Young. We are particularly grateful for detailed comments from Roger Miket. Contents List of Figs 1. Introduction 1 2. Gaps in knowledge: Zone A 2 2.1 The Site 2 2.2 The Hillfort 4 2.3 Environment 5 2.4 Cemetery evidence 6 2.5 Objects: the post-excavation archive 7 2.6 Later developments and the afterlife of Ad Gefrin 8 3. Gaps in knowledge: Zone B 9 3.1 Settlement patterns 9 3.2 Cemeteries 11 3.3 Environmental 12 3.4. Routes and communications 13 4. Potential of the Resource 14 5. Key Research Priorities: Zone A 15 5.1 The post-excavation archive 15 5.2 On-site re-assessment of the chronological sequence 16 5.3 Relationships with Milfield 19 5.4 Environment 19 5.5 The Hillfort 20 5.6 Short-term and long-term developments after Ad Gefrin 21 6. Key Research Priorities: Zone B 21 6.1 Settlement activity 21 6.2 Environment 23 6.3 Communications 24 7. Summary 24 8. Bibliography 25 Figures 31 List of Figures Fig. 1 Parameters for research area: Zone A – the site and its immediate 32 environs; Zone B – the hinterland Fig. 2 Aerial photograph of Yeavering showing the cropmarks to the south of 32 the road. -

Mourning the Sacrifice Behavior and Meaning Behind Animal Burials

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK Mourning the Sacrifice Behavior and Meaning behind Animal Burials JAMES MORRIS The remains of animals, fragments of bone and horn, are often the most common finds recovered from archaeological excavations. The potential of using this mate- rial to examine questions of past economics and environment has long been recognized and is viewed by many archaeologists as the primary purpose of animal remains. In part this is due to the paradigm in which zooarchaeology developed and a consequence of prac- titioners’ concentration on taphonomy and quantification.1 But the complex intertwined relationships between humans and animals have long been recognized, a good example being Lévi-Strauss’s oft quoted “natural species are chosen, not because they are ‘good to eat’ but because they are ‘good to think.’”2 The relatively recent development of social zooarchae- ology has led to a more considered approach to the meanings and relationships animals have with past human cultures.3 Animal burials are a deposit type for which social, rather than economic, interpretations are of particular relevance. When animal remains are recovered from archaeological sites they are normally found in a state of disarticulation and fragmentation, but occasionally remains of an individual animal are found in articulation. These types of deposits have long been noted in the archaeological record, although their descriptions, such as “special animal deposit,”4 can be heavily loaded with interpretation. In Europe some of the earliest work on animal buri- als was Behrens’s investigation into the “Animal skeleton finds of the Neolithic and Early Metallic Age,” which discussed 459 animal burials from across Europe.5 Dogs were the most common species to be buried, and the majority of these cases were associated with inhumations. -

An Examination of Regionality in the Iron Age Settlements and Landscape of West Wales

STONES, BONES AND HOMES: An Examination of Regionality in the Iron Age Settlements and Landscape of West Wales Submitted by: Geraldine Louise Mate Student Number 31144980 Submitted on the 3rd of November 2003, in partial fulfilment of the requirements of a Bachelor of Arts with Honours Degree School of Social Science, University of Queensland This thesis represents original research undertaken for a Bachelor of Arts Honours Degree at the University of Queensland, and was completed during 2003. The interpretations presented in this thesis are my own and do not represent the view of any other individual or group Geraldine Louise Mate ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page i Declaration ii Table of Contents iii List of Tables vi List of Figures vii Abstract ix Acknowledgements x 1. The Iron Age in West Wales 1 1.1 Research Question 1 1.2 Area of Investigation 2 1.3 An Approach to the Iron Age 2 1.4 Rationale of Thesis 5 1.5 Thesis Content and Organisation 6 2. Perspectives on Iron Age Britain 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Perspectives on the Iron Age 7 2.2.1 Progression of Interpretations 8 2.2.2 General Picture of Iron Age Society 11 2.2.3 Iron Age Settlements and Structures, and Their Part in Ritual 13 2.2.4 Pre-existing Landscape 20 2.3 Interpretive Approaches to the Iron Age 20 2.3.1 Landscape 21 2.3.2 Material Culture 27 2.4 Methodology 33 2.4.1 Assessment of Methods Available 33 2.4.2 Methodology Selected 35 2.4.3 Rationale and Underlying Assumptions for the Methodology Chosen 36 2.5 Summary 37 iii 3. -

The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles

www.RodnoVery.ru www.RodnoVery.ru The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles www.RodnoVery.ru Callanish Stone Circle Reproduced by kind permission of Fay Godwin www.RodnoVery.ru The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles Their Nature and Legacy RONALD HUTTON BLACKWELL Oxford UK & Cambridge USA www.RodnoVery.ru Copyright © R. B. Hutton, 1991, 1993 First published 1991 First published in paperback 1993 Reprinted 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998 Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford 0X4 1JF, UK Blackwell Publishers Inc. 350 Main Street Maiden, Massachusetts 02148, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Hutton, Ronald The pagan religions of the ancient British Isles: their nature and legacy / Ronald Hutton p. cm. ISBN 0-631-18946-7 (pbk) 1. -

Hambledon Hill National Nature Reserve Man’S Influence on Hambledon Hill Has Been Hambledon Hill Profound, but Spread Across Thousands of Years

Hambledon Hill National Nature Reserve Man’s influence on Hambledon Hill has been Hambledon Hill profound, but spread across thousands of years. The ancient forests that at one time covered most National Nature Reserve of lowland Britain were probably cleared from Hambledon Hill is an exceptional place for wildlife around Hambledon when Neolithic people settled and archaeology. The Reserve covers 74 hectares there more than 5000 years ago. and lies four miles north-west of Blandford between the Stour and Iwerne valleys. Rising to 192 The open grassland developed as successive metres above sea level it affords superb views over civilizations cleared the trees and grazed their the surrounding countryside. livestock. The earthworks, perhaps the biggest influence on the hill, have added many steeper Only a few fragments of Dorset’s once common slopes which favour Hambledon’s special wildlife. chalk grassland remain. Hambledon’s extensive Most of the grassland remains untouched by grassland with its variety of slope and aspect fertilisers or herbicides. provide the nature conservation interest for which Hambledon Hill was declared a National Nature Reserve. The archaeological remains are of international importance and are protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument. The grasslands The thin chalky soils on the steep rampart slopes 1. Quaking grass 2. Salad burnet are dry and infertile; ideal conditions for fine 3. Horseshoe vetch grasses, sedges and an astonishing variety of 4. Wild thyme flowering plants. The gullies between the ramparts 5. Chalk milkwort are dominated by vigorous grasses and plants 6. Mouse-ear hawkweed such as nettles because the soil is deeper and more fertile.