Excavations at Fin Cop, Derbyshire: an Iron Age Hillfort in Conflict?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

Ancient Defensive Earthworks Fortified

CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES IN UNION WITH THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF LONDON. SCHEME FOR RECORDING ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. 1903. COMMITTEE FOR RECORDING ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. LORD BALCARRES, M.P., F.S.A., Chairman. W. J. ANDREW, F.S.A. F. HAVERFIELD, F.S.A., MA. F. W. ATTREE (Lt.-Col. R.E.), W. H. ST. J. HOPE, M.A. F.S.A. BOYD DAWICINS (Prof.), F.R.S., J. HORACE ROUND, M.A. F.S.A. SIR JOHN EVANS, K.C.B., F.R.S., O. E. RUCK (Lt.-Col. RE.), V.P.S.A. F.S.A.Sc. A. R. GODDARD, B.A. W. M. TAPP, LL.D. BERTRAM C. A. WINDLE (Prof.), F.R.S., F.S.A. I. CHALKLEY GOULD, Hon. Sec. {Royal Societies' Club, St. James's Street, London.) EXTRACT from the Report of the Provisional Committee to the Congress of Archaeological Societies :— "There is need, not only for schedules such as this Committee is appointed to secure, but also for active antiquaries in all parts of the country to keep keen watch over ancient fortifications of earth and stone, and to endeavour to prevent their destruction by the hand of man in this utilitarian age." SCHEME FOR RECORDING ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. » T the Congress of the Archaeological Societies, held on A July ioth, 1901, a Committee was appointed to prepare a scheme for a systematic record of ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. It was suggested that the secretaries of the various archaeological societies, and other gentlemen likely to be interested in the subject, should be pressed to prepare schedules of the works in their respective districts, in the hope that lists may eventually be published. -

The Impact of Bayesian Chronologies on the British Iron Age

n Hamilton, D., Haselgrove, C., and Gosden, C. (2015) The impact of Bayesian chronologies on the British Iron Age. World Archaeology. Copyright © 2015 The Authors This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (CC BY 4.0) Version: Published http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/106441/ Deposited on: 11 June 2015 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk This article was downloaded by: [University of Glasgow] On: 11 June 2015, At: 06:03 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK World Archaeology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwar20 The impact of Bayesian chronologies on the British Iron Age William Derek Hamiltona, Colin Haselgroveb & Chris Gosdenc a University of Glasgow and University of Leicester b University of Leicester c University of Oxford Published online: 09 Jun 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: William Derek Hamilton, Colin Haselgrove & Chris Gosden (2015): The impact of Bayesian chronologies on the British Iron Age, World Archaeology, DOI: 10.1080/00438243.2015.1053976 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2015.1053976 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. -

Youlgrave's New Golf Society Tees

The Bugle A chance to blow your trumpet for the villagers of Alport, Middleton and Youlgrave No. 60 November 2003 Youlgrave’s new golf society tees off Although the George Hotel is best known for its darts and dominoes, the colourful village pub has become the unlikely base for Youlgrave’s budding golfers. The Conksbury Golf Society was established in May of this year, and at present has 12 members. Last month they enjoyed an outing to Shirland Golf Course, between Alfreton and Clay Cross, with Owen ’Taffy’ Jones emerging as the winner with 18 Stapleford points. He was presented with the prestigious egg cup trophy by the George Hotel’s Stephen Marsh (pictured right). Other members of the society Stephen Marsh (right) of the George Hotel presents who turned out for the October Owen ‘Taffy’ Jones with the egg cup trophy. round included Chris Cooke, Steve Hope, Adrian Murray, Gordon Coupe, John Montgomery and should contact Stephen Marsh at the Stephen Marsh. George Hotel (tel 636292). The Conksbury Golf Society welcomes For details of how the George’s darts new members – regardless of experience and domino teams are faring see ‘Pommie or ability – and anyone interested in joining Briefs’ on page 3. Published by the Bugle. Editor: Andrew McCloy, Greystones Cottage, Bankside, Youlgrave DE45 1WD, tel. 01629 636125, e-mail [email protected]. Contributions for the next issue to arrive by the 15th of the month. The views in this publication are not necessarily those of the editorial team. www.thebugle.org.uk. Printed by Greenaway Workshop, Hackney, Matlock (tel. -

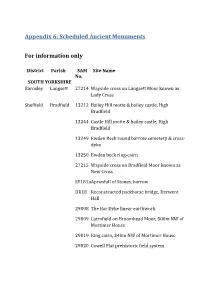

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER SURVEYS OF PREHISTORIC STONE CIRCLES IN BRITAIN, 1986. by A. Jensine Andresen and Mark Bonchek of Princeton University. Copyright: A. Jensine Andresen, Mark Bonchek and the New Horizons Research Foundation. November 1986. CONTENTS. Introductory Note. Magnetic Surveying Project Report on Geomantic Resea England, June 16 - July 22, 1986. Selected Notes. Bibliography. 1. Introductory Note. This report deals with a piece of research falling within the group of enquiries comprised under the term "geomancy". which has come into use during the past twenty years or so to connote what could perhaps be called the as yet somewhat speculative study of various presumed subtle or occult properties of terrestrial landscapes and the earth beneath them. In earlier times the word "geomancy" was used rather differently in relation to divination or prophecy carried out by means of some aspect of the earth, but nowadays it refers to the study of what might be loosely called "earth mysteries". These include the ancient Chinese lore and practical art of Fengshui -- the correct placing of buildings with respect to the local conformation of hills and dales, the orientation of medieval churches, the setting of buildings and monuments along straight lines (i.e. the so-called ley lines or leys). These topics all aroused interest in the early decades of the present century. Similarly,since about 1900 interest in megalithic monuments throughout western Europe has steadily increased. This can be traced to a variety of causes, which include increased study and popularisation of anthropology, folklore and primitive religion (e.g. -

Rude Stone Monuments Chapt

RUDE STONE MONUMENTS IN ALL COUNTRIES; THEIR AGE AND USES. BY JAMES FERGUSSON, D. C. L., F. R. S, V.P.R.A.S., F.R.I.B.A., &c, WITH TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY-FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS. LONDON: ,JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET. 1872. The right of Translation is reserved. PREFACE WHEN, in the year 1854, I was arranging the scheme for the ‘Handbook of Architecture,’ one chapter of about fifty pages was allotted to the Rude Stone Monuments then known. When, however, I came seriously to consult the authorities I had marked out, and to arrange my ideas preparatory to writing it, I found the whole subject in such a state of confusion and uncertainty as to be wholly unsuited for introduction into a work, the main object of which was to give a clear but succinct account of what was known and admitted with regard to the architectural styles of the world. Again, ten years afterwards, while engaged in re-writing this ‘Handbook’ as a History of Architecture,’ the same difficulties presented themselves. It is true that in the interval the Druids, with their Dracontia, had lost much of the hold they possessed on the mind of the public; but, to a great extent, they had been replaced by prehistoric myths, which, though free from their absurdity, were hardly less perplexing. The consequence was that then, as in the first instance, it would have been necessary to argue every point and defend every position. Nothing could be taken for granted, and no narrative was possible, the matter was, therefore, a second time allowed quietly to drop without being noticed. -

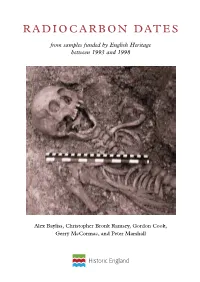

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

Settlement Hierarchy and Social Change in Southern Britain in the Iron Age

SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN IN THE IRON AGE BARRY CUNLIFFE The paper explores aspects of the social and economie development of southern Britain in the pre-Roman Iron Age. A distinct territoriality can be recognized in some areas extending over many centuries. A major distinction can be made between the Central Southern area, dominated by strongly defended hillforts, and the Eastern area where hillforts are rare. It is argued that these contrasts, which reflect differences in socio-economic structure, may have been caused by population pressures in the centre south. Contrasts with north western Europe are noted and reference is made to further changes caused by the advance of Rome. Introduction North western zone The last two decades has seen an intensification Northern zone in the study of the Iron Age in southern Britain. South western zone Until the early 1960s most excavation effort had been focussed on the chaiklands of Wessex, but Central southern zone recent programmes of fieid-wori< and excava Eastern zone tion in the South Midlands (in particuiar Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire) and in East Angiia (the Fen margin and Essex) have begun to redress the Wessex-centred balance of our discussions while at the same time emphasizing the social and economie difference between eastern England (broadly the tcrritory depen- dent upon the rivers tlowing into the southern part of the North Sea) and the central southern are which surrounds it (i.e. Wessex, the Cots- wolds and the Welsh Borderland. It is upon these two broad regions that our discussions below wil! be centred. -

Peak District Mines Historical Society Ltd

Peak District Mines Historical Society Ltd. Newsletter No. 142 April 2012 The Observations and Discoveries; Their Tenth Birthday! In this Newsletter we depart from what has become tradition and do not have a normal issue of Peak District Mines Observations and Discoveries, but instead have an index of the first forty sets of notes; ten years on since the first, this seems a perfect time to do this. The onerous task of compiling this index has fallen to Adam Russell, who very kindly volunteered to do this without prompting from us. We are very grateful. When we started I don’t think we ever envisaged there would be so many notes and with failing memory there is an increasing need to have an index to help easily find the various jottings when we need to refer back to something. We also take this opportunity to thank the many people who have contributed notes over the years – these have enlivened the Observations and Discoveries no end. This said, we always need more – if you have found something new or interesting, explored a shaft people don’t often go down or entered a mine where there is no readily available description of what is there, please consider writing a short note. There are literally hundreds of mines in the Peak where we have no idea what lies below ground – most were presumably explored in the 60s or 70s but often nothing was written down, and a new generation is now having to reinvent the wheel. We were gratified to learn, from the Reader Survey on the content of the newsletter that Steve undertook last year, just how much you, the readers, appreciated these notes. -

Hope to Hathersage Or Bamford Via Castleton

Hope to Hathersage (via Castleton) Hope to Bamford (via Castleton) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 17th August 2020 Current status Document last updated Wednesday, 19th August 2020 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2019-2020, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Hope to Hathersage or Bamford (via Castleton) Start: Hope Station Finish: Hathersage or Bamford Stations Hope Station, map reference SK 180 832, is 18 km south west of Sheffield, 231 km north west of Charing Cross and 169m above sea level. Bamford Station, map reference SK 207 825, is 3 km south east of Hope Station and 151m above sea level.