Rude Stone Monuments Chapt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

The Recumbent Stone Circles of Aberdeenshire

The Recumbent Stone Circles of Aberdeenshire The Recumbent Stone Circles of Aberdeenshire: Archaeology, Design, Astronomy and Methods By John Hill The Recumbent Stone Circles of Aberdeenshire: Archaeology, Design, Astronomy and Methods By John Hill This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by John Hill All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6585-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6585-2 This book is dedicated to: Dr Joan J Taylor (1940-2019) Dr Aubrey Burl (1926-2020) “What was once considered on the fringe of archaeology, now becomes mainstream” and to Rocky (2009-2020) “My faithful companion who walked every step of the way with me across the Aberdeenshire landscape” TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................ ix List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xiii Introduction ............................................................................................... -

The Origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 the Avebury Henge Is One of the Famous Mega

1 The origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2Mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 The Avebury henge is one of the famous mega- 7 lithic monuments of the European Neolithic, Research 8 yet much remains unknown about the detail 9 and chronology of its construction. Here, the 10 results of a new geophysical survey and 11 re-examination of earlier excavation records 12 illuminate the earliest beginnings of the 13 monument. The authors suggest that Ave- ’ 14 bury s Southern Inner Circle was constructed 15 to memorialise and monumentalise the site ‘ ’ 16 of a much earlier foundational house. The fi 17 signi cance here resides in the way that traces 18 of dwelling may take on special social and his- 19 torical value, leading to their marking and 20 commemoration through major acts of monu- 21 ment building. 22 23 Keywords: Britain, Avebury, Neolithic, megalithic, memory 24 25 26 Introduction 27 28 Alongside Stonehenge, the passage graves of the Boyne Valley and the Carnac alignments, the 29 Avebury henge is one of the pre-eminent megalithic monuments of the European Neolithic. ’ 30 Its 420m-diameter earthwork encloses the world s largest stone circle. This in turn encloses — — 31 two smaller yet still vast megalithic circles each approximately 100m in diameter and 32 complex internal stone settings (Figure 1). Avenues of paired standing stones lead from 33 two of its four entrances, together extending for approximately 3.5km and linking with 34 other monumental constructions. Avebury sits within the centre of a landscape rich in 35 later Neolithic monuments, including Silbury Hill and the West Kennet palisade enclosures 36 (Smith 1965; Pollard & Reynolds 2002; Gillings & Pollard 2004). -

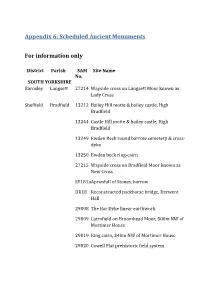

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER SURVEYS OF PREHISTORIC STONE CIRCLES IN BRITAIN, 1986. by A. Jensine Andresen and Mark Bonchek of Princeton University. Copyright: A. Jensine Andresen, Mark Bonchek and the New Horizons Research Foundation. November 1986. CONTENTS. Introductory Note. Magnetic Surveying Project Report on Geomantic Resea England, June 16 - July 22, 1986. Selected Notes. Bibliography. 1. Introductory Note. This report deals with a piece of research falling within the group of enquiries comprised under the term "geomancy". which has come into use during the past twenty years or so to connote what could perhaps be called the as yet somewhat speculative study of various presumed subtle or occult properties of terrestrial landscapes and the earth beneath them. In earlier times the word "geomancy" was used rather differently in relation to divination or prophecy carried out by means of some aspect of the earth, but nowadays it refers to the study of what might be loosely called "earth mysteries". These include the ancient Chinese lore and practical art of Fengshui -- the correct placing of buildings with respect to the local conformation of hills and dales, the orientation of medieval churches, the setting of buildings and monuments along straight lines (i.e. the so-called ley lines or leys). These topics all aroused interest in the early decades of the present century. Similarly,since about 1900 interest in megalithic monuments throughout western Europe has steadily increased. This can be traced to a variety of causes, which include increased study and popularisation of anthropology, folklore and primitive religion (e.g. -

3 Avebury Info

AVEBURY HENGE & WEST KENNET AVENUE Information for teachers A henge is a circular area enclosed by a bank or ditch, Four or five thousand years ago there were as many as used for religious ceremonies in prehistoric times. 200-300 henges in use. They were mostly constructed Avebury is one of the largest henges in the British Isles. with a ditch inside a bank and some of them had stone Even today the bank of the henge is 5m above the or wooden structures inside them. Avebury has four modern ground level and it measures over one kilome- entrances, whereas most of the others have only one or tre all the way round. The stone circle inside the bank two. and ditch is the largest in Europe. How are the stones arranged? The outer circle of standing stones closely follows the circuit of the ditch. There were originally about 100 stones in this circle, of which 30 are still visible today. The positions of another 16 are marked with concrete pillars. Inside the northern and southern halves of the outer circle are two more stone circles, each about 100m in diameter. Only a small number of their original stones have survived. There were other stone settings inside these circles, including a three-sided group within the southern circle, known as ‘the Cove’. The largest stone that remains from this group weighs about 100 tonnes and is one of the largest megaliths in Britain. What is sarsen stone? Sarsen is a type of sandstone and is found all over the chalk downland of the Marlborough Downs. -

Jersey's Spiritual Landscape

Unlock the Island with Jersey Heritage audio tours La Pouquelaye de Faldouët P 04 Built around 6,000 years ago, the dolmen at La Pouquelaye de Faldouët consists of a 5 metre long passage leading into an unusual double chamber. At the entrance you will notice the remains of two dry stone walls and a ring of upright stones that were constructed around the dolmen. Walk along the entrance passage and enter the spacious circular main Jersey’s maritime Jersey’s military chamber. It is unlikely that this was ever landscape landscape roofed because of its size and it is easy Immerse Download the FREE audio tour Immerse Download the FREE audio tour to imagine prehistoric people gathering yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org the history the history here to worship and perform rituals. and stories and stories of Jersey of Jersey La Hougue Bie N 04 The 6,000-year-old burial site at Supported by Supported by La Hougue Bie is considered one of Tourism Development Fund Tourism Development Fund the largest and best preserved Neolithic passage graves in Europe. It stands under an impressive mound that is 12 metres high and 54 metres in diameter. The chapel of Notre Dame de la Clarté Jersey’s Maritime Landscape on the summit of the mound was Listen to fishy tales and delve into Jersey’s maritime built in the 12th century, possibly Jersey’s spiritual replacing an older wooden structure. past. Audio tour and map In the 1990s, the original entrance Jersey’s Military Landscape to the passage was exposed during landscape new excavations of the mound. -

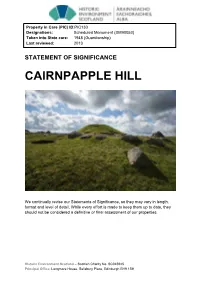

Cairnpapple Hill Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC130 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90053) Taken into State care: 1948 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2013 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE CAIRNPAPPLE HILL We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH CAIRNPAPPLE HILL SYNOPSIS Cairnpapple Hill is one of the best-known prehistoric sites on the mainland of Scotland. Archaeological excavations in 1947-8 revealed that the place had been the focus of communal activity for over 200 generations of local farmers, from the early Neolithic (c. -

Session 1 Time Travel in the Peak District from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic Aims of the Session Curriculum Links Resources

Stone Age to Iron Age KS2 Session 1 Time travel in the Peak District from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic Aims of the session The aim of this session is to explore the evidence of life in the local area from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic. Gather evidence in the gallery to create a video back at school about life in the Mesolithic times. Curriculum links This session will support pupils to develop a chronologically secure knowledge and understanding of British, local and world history, establishing clear narratives within and across the periods they study. They should note connections, contrasts and trends overtime and develop the appropriate use of historical terms. They should regularly address and sometimes devise historically valid questions about change, cause, similarity and difference, and significance. They should construct informed responses that involve thoughtful selection and organisation of relevant historical information. They should understand how our knowledge of the past is constructed from a range of sources. A visit to the Wonders of the Peak gallery will contribute to both an overview and a depth study to help pupils understand both the long arc of development and complexity of specific aspects of the content. Resources Handling collection, Stone Age Boy, DK Find out series, Stone Age Stone Age to Iron Age KS2 KS2 Session 1: 12,000 to 6,000 years ago The aim of this session is to explore the evidence of life in the local area from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic. Gather evidence in the gallery to create a video back at school about life in the Mesolithic times. -

Stonehenge and Megalithic Europe

Alan Mattlage, February 1st. 1997 Stonehenge and Megalithic Europe Since the 17th century, antiquarians and archeologists have puzzled over Stonehenge and similar megalithic monuments. Our understanding of these monuments and their builders has, however, only recently gone beyond very preliminary speculation. With the advent of radiocarbon dating and the application of a variety of sciences, a rough picture of the monument builders is slowly taking shape. The remains of deep sea fish in Mesolithic trash heaps indicate that northern Europeans had developed a sophisticated seafaring society by 4500 BC. The subsequent, simultaneous construction of megalithic monuments in Denmark-Sweden, Brittany, Portugal, and the British Isles indicates the geographic distribution of the society's origins, but eventually, monument construction occurred all across northwestern Europe. The monument builders' way of life grew out of the mesolithic economy. Food was gathered from the forest, hunted, or collected from the sea. By 4000 they began clearing patches of forest to create an alluring environment for wild game as well as for planting crops. This marks the start of the Neolithic period. Their material success produced the first great phase of megalithic construction (c. 4200 to 3200). The earliest monuments were chambered tombs, built by stacking enormous stones in a table-like structures, called "dolmens," which were then covered with earth. We call the resulting tumuli a "round barrow." Local variations of this monument-type can be identified. Elaborate "passage graves" were built in eastern Ireland. Elaborate "passage graves" were built in eastern Ireland. These were large earthen mounds covering a corridor of stones leading to a corbeled chamber. -

Neolithic Houses from Llanfaethlu, Anglesey Number 81 Autumn 2015

THE NEWSLETTERAST OF THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY P Registered Office: University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, London WC1H 0PY http://www.prehistoricsociety.org/ Neolithic houses from Llanfaethlu, Anglesey C.R Archaeology was commissioned by Isle of Anglesey The houses County Council to undertake a programme of archaeological House 1 is the largest of the structures and associated works at Llanfaethlu, Anglesey. The site is located on the with a large but ephemeral spread of relict soil which had north-eastern slope of a low hill overlooking a river. Three accumulated in a natural hollow outside the building. Early Neolithic houses, a large Middle Neolithic pit group This probably represents an activity or refuse disposal area. and two features with Grooved Ware pottery have been The house is not yet fully excavated (excavation will be excavated. Llanfaethlu is the first Early Neolithic multi-house completed this autumn), but is in excess of 16 m by 7 m settlement in north-west Wales, and whilst it has some striking and is oriented on a north-east–south-west axis. A number of resemblances to the houses at Llandegai and Parc Cybi it is different construction methods were utilised in the erection exceptional in terms of the artefactual assemblage and the level of the outer walls, ranging from stone-lined postholes in the of preservation. There is a strong resemblance to Irish sites north-east to wall slots and stakeholes in the south-east wall. where a recurring pattern of two or three buildings clustered Charcoal in one of the wall slots suggests that fire played a together is evident. -

Archaeological Research Agenda for the Avebury World Heritage Site

This volume draws together contributions from a number of specialists to provide an agenda for future research within the Avebury World Heritage Site. It has been produced in response to the English Heritage initiative for the development of regional and period research frameworks in England and represents the first formal such agenda for a World Heritage Site. Following an introduction setting out the background to, need for and development of the Research Agenda, the volume is presented under a series of major headings. Part 2 is a resource assessment arranged by period from the Lower Palaeolithic to the end of the medieval period (c. AD 1500) together with an assessment of the palaeo-environmental data from the area. Part 3 is the Research Agenda itself, again arranged by period but focusing on a variety of common themes. A series of more over-arching, landscape-based themes for environmental research is also included. In Part 4 strategies for the implementation of the Research Agenda are explored and in Part 5 methods relevant for that implementation are presented. Archaeological Research Agenda for the Avebury World Heritage Site Avebury Archaeological & Historical Research Group (AAHRG) February 2001 Published 2001 by the Trust for Wessex Archaeology Ltd Portway House, Old Sarum Park, Salisbury SP4 6EB Wessex Archaeology is a Registered Charity No. 287786 on behalf of English Heritage and the Avebury Archaeological & Historical Research Group Copyright © The individual authors and English Heritage all rights reserved British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 1–874350–36–1 Produced by Wessex Archaeology Printed by Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge The cost of this publication was met by English Heritage Front Cover: Avebury: stones at sunrise (© English Heritage Photographic Library.