Prehistoric Henges and Circles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burial Mounds in Europe and Japan Comparative and Contextual Perspectives

Comparative and Global Perspectives on Japanese Archaeology Burial Mounds in Europe and Japan Comparative and Contextual Perspectives edited by Access Thomas Knopf, Werner Steinhaus and Shin’ya FUKUNAGAOpen Archaeopress Archaeopress Archaeology © Archaeopress and the authors, 2018. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78969 007 1 ISBN 978 1 78969 008 8 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the authors 2018 © All image rights are secured by the authors (Figures edited by Werner Steinhaus) Access Cover illustrations: Mori-shōgunzuka mounded tomb located in Chikuma-shi in Nagano prefecture, Japan, by Werner Steinhaus (above) Magdalenenberg burial mound at Villingen-Schwenningen, Germany,Open by Thomas Knopf (below) The printing of this book wasArchaeopress financed by the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Oxuniprint, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2018. Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................................................................................................... iii List of authors ................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Issue 3 Autumn 2010 Kirkstall Abbey and Abbey House Museum

TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2010 In this issue: Kirkstall Abbey and Abbey House Museum Mysterious Carved Rocks on Ilkley Moor Along the Hambleton Drove Road The White Horse of Kilburn The Notorious Cragg Vale Coiners The Nunnington Dragon Hardcastle Crags in Autumn Hardcastle Crags is a popular walking destination, most visitors walk from Hebden Bridge into Hebden Dale. (also see page 13) 2 The Yorkshire Journal TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2010 Left: Fountains Cottage near the western gate of Fountains Abbey. Photo by Jeremy Clark Cover: Cow and Calf Rocks, Ilkley Moor Editorial utumn marks the transition from summer into winter when the arrival of night becomes noticeably earlier. It is also a great time to enjoy a walk in one of Yorkshire’s beautiful woodlands with their A magnificent display of red and gold leaves. One particularly stunning popular autumn walk is Hardcastle Crags with miles of un-spoilt woodland owned by the National Trust and starts from Hebden Bridge in West Yorkshire. In this autumn issue we feature beautiful photos of Hardcastle Crags in Autumn, and days out, for example Kirkstall Abbey and Abbey House Museum, Leeds, Mysterious carved rocks on Ilkley Moor, the Hambleton Drove Road and the White Horse of Kilburn. Also the story of the notorious Cragg Vale coiners and a fascinating story of the Nunnington Dragon and the knight effigy in the church of All Saints and St. James, Ryedale. In the Autumn issue: A Day Out At Kirkstall Abbey And Abbey The White Horse Of Kilburn That Is Not A House Museum,-Leeds True White Horse Jean Griffiths explores Kirkstall Abbey and the museum. -

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

A Pilgrimage to Avebury Stone Circles in Wiltshire

BEST OF BRITAIN A pilgrimage to Avebury stone circles in Wiltshire ere are famous religious pilgrimages, there are also the pilgrimages that one does for oneself. It doesn't have to be on foot or by any particular mode of transport. It is nothing more than the journey of getting to the desired destination, in any way or form. For me, that desired destination was the stone circles of Avebury in Wiltshire, for years I’ve been yearning to sit in stone circles and visit the sacred sites of Europe. So, why visit Avebury, a place that is often sold to us as the poor cousin of the ever-famous Stonehenge? In real - ity, it is not less but much more. Why Avebury? is sacred Neolithic site is the largest set of stone circles out of the thousands in the United Kingdom and in the world. It is older than other sites, although the dating is sketchy. I've heard everything from 2600BC to 4500BC and it’s still up for discussion. Despite being a World Heritage site, Avebury is fully open to the public. Unlike Stonehenge, you can walk in and around the stones. It is accessible by public transport, buses stop in the middle of the village, and the entrance is free. As well as the stone cir - cles, there is also an avenue of stones that take you down to the West Kennet Long Barrow and Silbury Hill. Onsite for a small fee you can visit the museum and manor that are run by the National Trust. -

Concrete Prehistories: the Making of Megalithic Modernism 1901-1939

Concrete Prehistories: The Making of Megalithic Modernism Abstract After water, concrete is the most consumed substance on earth. Every year enough cement is produced to manufacture around six billion cubic metres of concrete1. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern prehistories. We present an archaeology of concrete in the prehistoric landscapes of Stonehenge and Avebury, where concrete is a major component of megalithic sites restored between 1901 and 1964. We explore how concreting changed between 1901 and the Second World War, and the implications of this for constructions of prehistory. We discuss the role of concrete in debates surrounding restoration, analyze the semiotics of concrete equivalents for the megaliths, and investigate the significance of concreting to interpretations of prehistoric building. A technology that mixes ancient and modern, concrete helped build the modern archaeological imagination. Concrete is the substance of the modern –”Talking about concrete means talking about modernity” (Forty 2012:14). It is the material most closely associated with the origins and development of modern architecture, but in the modern era, concrete has also been widely deployed in the preservation and display of heritage. In fact its ubiquity means that concrete can justifiably claim to be the single most dominant substance of heritage conservation practice between 1900 and 1945. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern pasts, and in particular, modern prehistories. As the pre-eminent marker of modernity, concrete was used to separate ancient from modern, but efforts to preserve and display prehistoric megaliths saw concrete and megaliths become entangled. -

BA0063 2013-001 Radial Leaded Capacitor Assembly Location Change Notification Jan 13 Final

Syfer Technology Limited Old Stoke Road Arminghall, Norwich, Norfolk NR14 8SQ England Tel: +44 (0)1603 723347 Fax +44 (0)1603 723301 Email: [email protected] Web: www.syfer.com Anglia Sandall Road Wisbech Cambridgeshire PE13 2PS United Kingdom BA0063 February 2013 PCN reference: 2013/01 Subject: Radial Leaded Capacitor Assembly Location Change Dear Customer, Syfer Technology Ltd has been manufacturing radial leaded capacitors at our UK manufacturing facility from the early 1980s. Due to facility space requirements needed to develop and manufacture new products, it has been decided to sub-contract the radial assembly process. Ceramic Chip Capacitor Encapsulation Material Lead to Chip Capacitor Solder Joint Lead Fig. 1. Radial Capacitor Construction Diagram The critical part of the radial component (the ceramic chip capacitor) will still be manufactured, electrically tested and inspected by Syfer. Registered Office: Old Stoke Road Arminghall, Norwich NR14 8SQ England Registered in England: No 2092166 (FA4/971/1) The radial assembly process including soldering leads onto the chip capacitor, encapsulation, print and radial electrical test will be conducted by the sub-contractor. The sub-contractor is certified to ISO9001 and has a proven history of manufacturing and supplying radial leaded capacitors. Syfer has conducted reliability tests on components manufactured by the sub-contractor as part of qualification and ongoing monitoring requirements. The change in location for the radial leaded capacitor assembly does not affect component specifications (including dimensional, performance or reliability) and, as such, there is no change to the Syfer part number. Radial leaded capacitors manufactured by the sub-contractor will gradually be phased into customer supply from March 2013. -

Relationships Between Round Barrows and Landscapes from 1500 Bc–Ac 1086

The University of Manchester Research Other Types of Meaning: Relationships between Round Barrows and Landscapes from 1500 bc–ac 1086 DOI: 10.1017/S0959774316000433 Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Cooper, A. (2016). Other Types of Meaning: Relationships between Round Barrows and Landscapes from 1500 bc–ac 1086. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 26(4), 665-696. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000433 Published in: Cambridge Archaeological Journal Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 Cambridge Archaeological Journal For Peer Review Other types of meaning: relationships between round barrows and -

The Lives of Prehistoric Monuments in Iron Age, Roman, and Medieval Europe by Marta Díaz-Guardamino, Leonardo García Sanjuán and David Wheatley (Eds)

The Prehistoric Society Book Reviews THE LIVES OF PREHISTORIC MONUMENTS IN IRON AGE, ROMAN, AND MEDIEVAL EUROPE BY MARTA DÍAZ-GUARDAMINO, LEONARDO GARCÍA SANJUÁN AND DAVID WHEATLEY (EDS) Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2015. 356pp, 50 figs, 32 B/W plates, 6 tables. ISBN 978-0-19-872460-5, hb, £85 This handsome book is the outcome of a session at the 2013 European Association of Archaeologists in Pilsen, organised by the editors on the cultural biographies of monuments. It is divided into three sections, with the main part comprising 13 detailed case-studies, framed on either side by shorter introduction and discussion pieces. There is variety in the chronologies, subject matters and geographical scopes addressed; in short there is something for almost everyone! In their Introduction, the editors advocate that archaeologists require a more reflexive conceptual toolkit to deal with the complex issues of monument continuity, transformation, re-use and abandonment, and the significance of the speed and the timing of changes. They also critique the loaded term ‘afterlife’ as this separates the unfolding biography of a monument, and unwittingly relegates later activities to lesser importance than its original function. In the following chapter, Joyce Salisbury explores how the veneration of natural places in the landscape, such as caves and mountains, was shifted to man-made monumental features over time. The bulk of the book focuses on the specific case-studies which span Denmark in the north to Tunisia in the south and from Ireland in the west to Serbia and Crete in the east. In Chapter 3, Steen Hvass’s account of the history of research at the monument complex of King’s Jelling in Denmark is fascinating, but a little heavy on stratigraphic narrative, and light on theory and discussion. -

Stonehenge and Avebury WHS Management Plan 2015 Summary

Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site Vision The Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site is universally important for its unique and dense concentration of outstanding prehistoric monuments and sites which together form a landscape without parallel. We will work together to care for and safeguard this special area and provide a tranquil, rural and ecologically diverse setting for it and its archaeology. This will allow present and future generations to explore and enjoy the monuments and their landscape setting more fully. We will also ensure that the special qualities of the World Heritage Site are presented, interpreted and enhanced where appropriate, so that visitors, the local community and the whole world can better understand and value the extraordinary achievements © K020791 Historic England © K020791 Historic of the prehistoric people who left us this rich legacy. Avebury Stone Circle We will realise the cultural, scientific and educational potential of the World Heritage Site as well as its social and economic benefits for the community. © N060499 Historic England © N060499 Historic Stonehenge in summer 2 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 World Heritage Sites © K930754 Historic England © K930754 Historic Arable farming in the WHS below the Ridgeway, Avebury The Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site is internationally important for its complexes of outstanding prehistoric monuments. Stonehenge is the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle in the world, while Avebury is Stonehenge and Avebury were inscribed as a single World Heritage Site in 1986 for their outstanding prehistoric monuments the largest. -

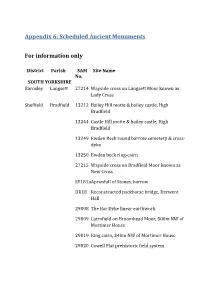

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER SURVEYS OF PREHISTORIC STONE CIRCLES IN BRITAIN, 1986. by A. Jensine Andresen and Mark Bonchek of Princeton University. Copyright: A. Jensine Andresen, Mark Bonchek and the New Horizons Research Foundation. November 1986. CONTENTS. Introductory Note. Magnetic Surveying Project Report on Geomantic Resea England, June 16 - July 22, 1986. Selected Notes. Bibliography. 1. Introductory Note. This report deals with a piece of research falling within the group of enquiries comprised under the term "geomancy". which has come into use during the past twenty years or so to connote what could perhaps be called the as yet somewhat speculative study of various presumed subtle or occult properties of terrestrial landscapes and the earth beneath them. In earlier times the word "geomancy" was used rather differently in relation to divination or prophecy carried out by means of some aspect of the earth, but nowadays it refers to the study of what might be loosely called "earth mysteries". These include the ancient Chinese lore and practical art of Fengshui -- the correct placing of buildings with respect to the local conformation of hills and dales, the orientation of medieval churches, the setting of buildings and monuments along straight lines (i.e. the so-called ley lines or leys). These topics all aroused interest in the early decades of the present century. Similarly,since about 1900 interest in megalithic monuments throughout western Europe has steadily increased. This can be traced to a variety of causes, which include increased study and popularisation of anthropology, folklore and primitive religion (e.g.