Dress Practices As Embodied Multimodal Rhetorics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports

By Ruth S. Barrett Th e Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports 74 Where the desperation of late-stage m 1120_WEL_Barrett_TulipMania [Print]_14155638.indd 74 9/22/2020 12:04:44 PM Photo Illustrations by Pelle Cass Among Ivy League– Obsessed Parents meritocracy is so strong, you can smell it 75 1120_WEL_Barrett_TulipMania [Print]_14155638.indd 75 9/22/2020 12:04:46 PM On paper, Sloane, a buoyant, chatty, stay-at-home mom from Faireld County, Connecticut, seems almost unbelievably well prepared to shepherd her three daughters through the roiling world of competitive youth sports. She played tennis and ran track in high school and has an advanced “I thought, What are we doing? ” said Sloane, who asked to be degree in behavioral medicine. She wrote her master’s thesis on the identied by her middle name to protect her daughters’ privacy connection between increased aerobic activity and attention span. and college-recruitment chances. “It’s the Fourth of July. You’re She is also versed in statistics, which comes in handy when she’s ana- in Ohio; I’m in California. What are we doing to our family? lyzing her eldest daughter’s junior-squash rating— and whiteboard- We’re torturing our kids ridiculously. ey’re not succeeding. ing the consequences if she doesn’t step up her game. “She needs We’re using all our resources and emotional bandwidth for at least a 5.0 rating, or she’s going to Ohio State,” Sloane told me. a fool’s folly.” She laughed: “I don’t mean to throw Ohio State under the Yet Sloane found that she didn’t know how to make the folly bus. -

CRISIS of PURPOSE in the IVY LEAGUE the Harvard Presidency of Lawrence Summers and the Context of American Higher Education

Institutions in Crisis CRISIS OF PURPOSE IN THE IVY LEAGUE The Harvard Presidency of Lawrence Summers and the Context of American Higher Education Rebecca Dunning and Anne Sarah Meyers In 2001, Lawrence Summers became the 27th president of Harvard Univer- sity. Five tumultuous years later, he would resign. The popular narrative of Summers’ troubled tenure suggests that a series of verbal indiscretions created a loss of confidence in his leadership, first among faculty, then students, alumni, and finally Harvard’s trustee bodies. From his contentious meeting with the faculty of the African and African American Studies Department shortly af- ter he took office in the summer of 2001, to his widely publicized remarks on the possibility of innate gender differences in mathematical and scientific aptitude, Summers’ reign was marked by a serious of verbal gaffes regularly reported in The Harvard Crimson, The Boston Globe, and The New York Times. The resignation of Lawrence Summers and the sense of crisis at Harvard may have been less about individual personality traits, however, and more about the context in which Summers served. Contestation in the areas of university governance, accountability, and institutional purpose conditioned the context within which Summers’ presidency occurred, influencing his appointment as Harvard’s 27th president, his tumultuous tenure, and his eventual departure. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution - Noncommercial - No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You may reproduce this work for non-commercial use if you use the entire document and attribute the source: The Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke University. -

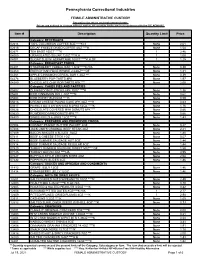

FEMALE ADMINISTRATIVE CUSTODY See Policy for Return and Replacement Terms

Pennsylvania Correctional Industries FEMALE ADMINISTRATIVE CUSTODY See policy for return and replacement terms. Prices are subject to change without notice. All quantity limits are in accordance with the DC ADM-815. Item # Description Quantity Limit Price Category: BEVERAGES 02614 100% COLUMBIAN COFFEE 5OZ ****K,H None 2.61 02616 DECAF FREEZE DRIED COFFEE 4OZ ****K None 1.54 02671 TEA BAGS 100CT ****K 1 2.46 04000 GRANULATED SUGAR 12OZ ****K,H 1 1.00 04001 SUGAR SUB W/ ASPARTAME 100CT ****K,H,GF 1 1.25 Category: BREAKFAST FOODS 04201 STRAWBERRY CEREAL BAR 1.3OZ ****K,H/A None 0.39 04260 ENERGY BAR,FDGE BRWNE 2.64OZ****GF None 1.31 04261 APPLE CINNAMON CEREAL BAR 1.3OZ *** None 0.39 04276 BLUEBERRY POP-TARTS 8PK None 1.97 04280 CHOCOLATE CHIP POP-TARTS 8PK *** None 2.00 Category: CAKES PIES AND PASTRIES 05602 DUNKIN DONUT STICKS 6PK 10OZ ****K None 1.36 05604 ICED CINNAMON ROLL 4OZ ****K None 0.62 05608 ICED HONEY BUN 6OZ ****K None 0.59 05616 CREAM CHEESE POUND CAKE 2PK 4OZ ****K None 0.63 05617 PEANUT BUTTER WAFERS 6-2PKS 12OZ ****K None 1.76 05628 CHOCOLATE COVERED MINI DONUTS 6PK *** None 0.66 05630 POWDERED MINI DONUTS 6PK *** None 0.66 06800 SWISS ROLLS 6-2PKS 12OZ ****K None 1.43 Category: PREPARED AND PRESERVED FOODS 07004 CREAMY PEANUT BUTTER PACKET 2OZ None 0.27 07406 JACK LINK'S ORIGINAL BEEF STEAK 2OZ None 2.21 07409 BACON SINGLES 6 SLICES .78OZ None 1.80 07411 BEEF & CHEESE STICK 1OZ None 0.57 07413 BEEF SUMMER SAUSAGE HOT 5OZ None 1.44 07414 BEEF SUMMER SAUSAGE REGULAR 5OZ None 1.44 07420 TURKEY SUMMER SAUSAGE SWEET 5OZ****GF -

Boxers Or Briefs Poll

Boxers Or Briefs Poll Fun Poll, Boxers or Briefs? Cast your vote and then share with your friends to get their vote. Welcome to Zity. 15%: Plain nondescript underwear. I personally prefer boxers, but they get so annoying. For women the options were briefs, bikini, shorts and thongs. Pants for sport, boxers otherwise. Seems it's a big deal with some of the younger crowd out there, (under 40) that says it's a big deal if you wear whitey tightys, boxers of briefs. 57% (647) Boxer briefs. Sam Talbot (Top Chef) - "boxers, briefs and commando" Rob Thomas (lead singer of Matchbox Twenty) Justin Timberlake (pop musician and actor) - started in briefs; switched to boxers; then to boxer briefs and sometimes commando; about boxer briefs, his current preference, he says: "like the way they hold everything together". 10 Answers. The new findings from the National Poll on Healthy Aging suggest that more physicians should routinely ask their older female patients about incontinence issues they might be experiencing. Tighty Whiteys are NOT cool (not saying you show your underwear to everyone). Share Followers 0. They also offer refastenable hook tabs and curved leg elastics like adult diapers for a fit that stays in place and helps you, or those you love, stay confident and comfortable. This comment has been removed by the author. Here's how to debrief his briefs. Kagura = 878 8. Boxers, Briefs and Battles. I in uncomplicated words switched to briefs/boxers, which ability i have were given lengthy lengthy previous from in uncomplicated words boxers to many times situations boxers, on get jointly briefs. -

HANESBRANDS INC GOING COMMANDO September 13, 2016 DISCLAIMER

BRIAN MCGOUGH ALEC RICHARDS JEREMY MCLEAN HANESBRANDS INC GOING COMMANDO September 13, 2016 DISCLAIMER DISCLAIMER Hedgeye Risk Management is a registered investment advisor, registered with the State of Connecticut. Hedgeye Risk Management is not a broker dealer and does not provide investment advice for individuals. This research does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. This research is presented without regard to individual investment preferences or risk parameters; it is general information and does not constitute specific investment advice. This presentation is based on information from sources believed to be reliable. Hedgeye Risk Management is not responsible for errors, inaccuracies or omissions of information. The opinions and conclusions contained in this report are those of Hedgeye Risk Management, and are intended solely for the use of Hedgeye Risk Management’s clients and subscribers. In reaching these opinions and conclusions, Hedgeye Risk Management and its employees have relied upon research conducted by Hedgeye Risk Management’s employees, which is based upon sources considered credible and reliable within the industry. Hedgeye Risk Management is not responsible for the validity or authenticity of the information upon which it has relied. TERMS OF USE This report is intended solely for the use of its recipient. Re-distribution or republication of this report and its contents are prohibited. For more details please refer to the appropriate sections of the Hedgeye Services Agreement and the Terms of Use at www.hedgeye.com © Hedgeye Risk Management LLC, All Rights Reserved. 2 PLEASE SUBMIT QUESTIONS* TO [email protected] *ANSWERED AT THE END OF THE CALL STILL CALLING IT LIKE WE SEE IT 1) Core business weakening. -

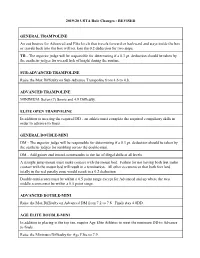

2019-20 USTA Rule Changes - REVISED

2019-20 USTA Rule Changes - REVISED GENERAL TRAMPOLINE An out bounce for Advanced and Elite levels that travels forward or backward and stays inside the box or travels back into the box will not lose the 0.2 deduction for two steps. TR - The superior judge will be responsible for determining if a 0.3 pt. deduction should be taken by the aesthetic judges for overall lack of height during the routine. SUB-ADVANCED TRAMPOLINE Raise the Max Difficulty on Sub-Advance Trampoline from 4.6 to 4.8. ADVANCED TRAMPOLINE MINIMUM: Seven (7) Somis and 4.9 Difficulty. ELITE OPEN TRAMPOLINE In addition to meeting the required DD - an athlete must complete the required compulsory skills in order to advance to finals. GENERAL DOUBLE-MINI DM - The superior judge will be responsible for determining if a 0.3 pt. deduction should be taken by the aesthetic judges for tumbling across the double-mini. DM - Add gainer and inward somersaults to the list of illegal skills at all levels. A straight jump mount must make contact with the mount bed. Failure for not having both feet make contact with the mount bed will result in a termination. All other occurrences that both feet land totally in the red penalty zone would result in a 0.2 deduction. Double-mini scores must be within a 0.5 point range except for Advanced and up where the two middle scores must be within a 0.5 point range. ADVANCED DOUBLE-MINI Raise the Max Difficulty on Advanced DM from 7.2 to 7.8 Finals stay 4.8DD. -

Take Ivy Was Originally Published Shosuke Ishizu Is the Representative Director in Japan in 1965, Setting Off an Explosion of of Ishizu Office

Teruyoshi Hayashida was born in the fashionable Aoyama District of Tokyo, where he also grew up. He began shooting cover images for Men’s Club magazine after the title’s launch. A sophisticated Photographs by Teruyoshi Hayashida dresser and a connoisseur of gourmet food, Text by Shosuke Ishizu, Toshiyuki Kurosu, he is known for his homemade, soy-sauce- and Hajime (Paul) Hasegawa marinated Japanese pepper (sansho), and his love of gunnel tempura and Riesling wine. Described by The New York Times as, “a treasure of fashion insiders,” Take Ivy was originally published Shosuke Ishizu is the representative director in Japan in 1965, setting off an explosion of of Ishizu Office. Originally born in Okayama American-influenced “Ivy Style” fashion among Prefecture, after graduating from Kuwasawa Design students in the trendy Ginza shopping district School he worked in the editorial division at Men’s of Tokyo. The product of four collegiate style Club until 1960 when he joined VAN Jacket Inc. enthusiasts, Take Ivy is a collection of candid He established Ishizu Office in 1983, and now photographs shot on the campuses of America’s produces several brands including Niblick. elite, Ivy League universities. The series focuses on men and their clothes, perfectly encapsulating Toshiyuki Kurosu was raised in Tokyo. He joined the unique student fashion of the era. Whether VAN Jacket Inc. in 1961, where he was responsible lounging in the quad, studying in the library, riding for the development of merchandise and sales bikes, in class, or at the boathouse, the subjects of promotion. He left the company in 1970 and Take Ivy are impeccably and distinctively dressed in started his own business, Cross and Simon. -

“THE IVY LOOK POCKET GUIDE” Interview by GSTAG

“THE IVY LOOK POCKET GUIDE” Interview by GSTAG. 1) Could you please introduce yourself? JP Gall: JP Gall, modernist, flaneur, salesman and author. Graham Marsh: Graham Marsh is an art director, illustrator and author. He never wears double breasted jackets or black shoes. 2) How did you both come to The Ivy Look? G.M.: As I said in the book, Ivy clothes were addictive. I got hooked the first time I saw them being worn by the pilgrims of modern jazz who inhabited the London based art Department of Marvel Comics where I first worked back in the early 1960s. It was an insider’s world of narrow lapelled sharp Ivy suits, narrow knitted ties and narrow haircuts. The soundtrack to this cool, detached world included the music of Miles Davis, Gerry Mulligan and Jimmy Smith. This was a world I wanted into and like a sponge proceeded to soak up all it had to offer. JP.G.: I made a concerted effort to be different from my peers. I was a teenager in the 1980s and I felt completely disconnected from the music and fashion of that period. It left me cold. I thank 2 people. Firstly Paul Weller who made me a mod, because from there it was a process of curiosity and research that led me on from elementary mod to the whole Ivy League thing. And I also need to thank John Simons, a mentor for many of us kids keen to get the feel of the original Ivy League jazz culture under our finger nails. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Blacklist100 E-Book 14JUL2020 V2.3

Table of Contents 04: Curatorial Note 10: Open Letter on Race 19: Short Essay: Celebrating Blackness on Juneteenth 25: Artist Statement & Works (Elizabeth Colomba) 28: Short Essay: Who sets the standards for equality (E’lana Jordan) 31: Category 1: Cause & Community 58: Category 2: Industry & Services 85: Spoken Word Poem: A-head of the School 86: Category 3: Marketing, Communication & Design 113: Spoken Word Poem: Culture Storm 114: Category 4: Media, Arts & Entertainment 141: Category 5: STEM & Healthcare 168: Full 2020 blacklist100 171: Closing Acknowledgements 2 Curatorial Note This e-book originated as a post on LinkedIn the week following the death of George Floyd. The post included an 8-page document entitled an “Open Letter on Race." The letter was released as a 25-minute video, also. The central theme of the letter was a reflection on Dr. Martin Luther King’s critical question: “Where do we go from here?" Leading into the week of Juneteenth, the Open Letter on Race received over 30,000 views, shares, and engagements. Friends were inspired to draft essays sharing their stories; and this book represents their collective energy. In the arc of history, we stand hopeful that we have now reached a long-awaited inflection point; this book is a demonstration that the People are ready to lead change. This e-book features 100 Black culture-makers & thought-leaders whose message is made for this moment. The theme of this book is “A Call for Change.” This interactive book will never be printed, and has embedded hyperlinks so you can take action now. -

Boxers Or Briefs? Neither

Boxers Or Briefs? Neither. It’s Trunks. By Deborah Weinswig for Forbes August 15, 2016 We recently teamed up Gen X: “Boxers Or Millennials: Defined By with First Insight, which Briefs?” Leads To “The The Trunk offers companies a platform Boxer Brief” for consumer testing of products, to analyze According to First Insight consumer tests of men’s In 1994, a high school data, prices of men’s trunk apparel conducted since student at an MTV - underwear have risen by 2013. The findings show sponsored town hall 44% over the past three that, although men’s apparel famously asked Bill Clinton, years, and the volume of prices overall have fallen by “Is it boxers or briefs?” He trunks tested via the 27.8% over the period, laughed and answered, company’s platform has men’s underwear prices “Usually briefs.” The fact boosted tests in the entire have, in fact, increased by that he answered at all men’s underwear category 34%. We also found that the endeared him to Gen Xers. by 34% over the same number of tests conducted on Around the same time, John period. In 2013, trunks men’s accessories via First Varvatos cut off a pair of accounted for just 8% of the Insight has grown by 681% long johns and called them total men’s underwear tests over the past three years. “boxer briefs.” Now, conducted via First Insight’s The popular BPOP according to data from The platform; in 2016 to date, +0.70% sock category, NPD Group, boxer briefs are they have represented 56% where the number of tests the dominant form of men’s of the total. -

Machine Learning (Ml) for Tracking the Geo-Temporality of a Trend: Documenting the Frequency of the Baseball-Trucker Hat on Social Media and the Runway

MACHINE LEARNING (ML) FOR TRACKING THE GEO-TEMPORALITY OF A TREND: DOCUMENTING THE FREQUENCY OF THE BASEBALL-TRUCKER HAT ON SOCIAL MEDIA AND THE RUNWAY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Rachel Rose Getman May 2019 © 2019 Rachel Rose Getman ABSTRACT This study applied fine-grained Machine Learning (ML) to document the frequency of baseball-trucker hats on social media with images populated from the Matzen et al. (2017) StreetStyle-27k Instagram dataset (2013-2016) and as produced in runway shows for the luxury market with images populated from the Vogue Runway database (2000-2018). The results show a low frequency of baseball-trucker hats on social media from 2013-2016 with little annual fluctuation. The Vogue Runway plots showed that baseball-hats appeared on the runway before 2008 with a slow but steady annual increase from 2008 through 2018 with a spike in 2016 to 2017. The trend is discussed within the context of social, cultural, and economic factors. Although ML requires refinement, its use as a tool to document and analyze increasingly complex trends is promising for scholars. The study shows one implementation of high-level concept recognition to map the geo-temporality of a fashion trend. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Rachel R. Getman holds a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). Her interests lie in the intersection of arts and sciences through interdisciplinary collaboration. The diversification of her professional experience from the service industry, education, wardrobe styling, apparel production, commercial vocals, and organic agriculture influence her advocacy for holistic thinking and non-linear problem solving.