Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Rights Abuses in Sudan Over the Month of March 20161 Overview

Human Rights Abuses in Sudan over the Month of March 20161 Overview During the month of March 2016, SUDO (UK)’s network of human rights monitors have reported and verified 65 incidents of human rights abuses across Sudan involving nine Sudanese states, whilst one such abuse was recorded in South Sudan relating to the arrest of two prominent Sudanese politicians who had participated in the National Dialogue by the security services of the Government of South Sudan. Monitors submitted a further two reports verifying the presence of a heavily armed group in North Darfur that is allegedly linked to ISIS in Libya, in addition to the troop movement of the Rapid Support Forces in South Kordofan. Enclosed within the 65 reports pertaining to human rights abuses, SUDO (UK) has assessed that various forces under the authority of the Government of Sudan2 were responsible, as individual entities, for 50 instances of human rights abuses, whilst various militias known collectively as Janjaweed were responsible for ten abuses. Unknown parties committed five such abuses, the various armed opposition movements four3, and the South Sudanese security service one such abuse. Once again it is worth stressing that multiple actors colluded in various incidents resulting in the fact that multiple perpetrators can be responsible for the same incident, hence 70 perpetrators have been identified for 65 human rights abuses. The 65 reports detail the following: the death 37 civilians and the serious injury of 59; the rape of 14 females including nine minors; the arrest of 28 persons including one detainee being held in a toxic container at the Sudanese Armed Forces Headquarters in Demazin; 15 reports of aerial bombardment resulting in the minimum use of some 160 bombs; the direct targeting of 30 civilian villages, which have been identified by monitors leading to the destruction of 15 of those villages; five incidents pertaining to press freedom with four newspaper confiscations; three dispersions of peaceful protest; and the denial of external travel to five persons. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations. -

Sudan Arming the Perpetrators of Grave Abuses in Darfur

Sudan Arming the perpetrators of grave abuses in Darfur Map The boundary between north and south Sudan runs south of Southern Darfur, Western Kordofan, Southern Kordofan, White Nile and Blue Nile States. The so-called 'marginal' areas are Abyei, Southern Kordofan/the Nuba mountains and Blue Nile State. Introduction "I was living with my family in Tawila and going to school when one day the Janjawid came and attacked the school. We all tried to leave the school but we heard noises of bombing and started running in all directions... The Janjawid caught some girls: I was raped by four men inside the school…When I went back to town, I found that they had destroyed all the buildings. Two planes and a helicopter had bombed the town. One of my uncles and a cousin were killed in the attack. " A 19- year-old woman, describing the attack on Tawila in February 2004.(1) Governments of countries named in this report that have allowed the supply of various types of arms to Sudan over the past few years have contributed to the capacity of Sudanese leaders to use their army and air force to carry out grave violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. Foreign governments have also enabled the government of Sudan to arm and deploy untrained and unaccountable militias that have deliberately and indiscriminately killed civilians in Darfur on a large scale, destroying homes, looting property and forcibly displacing the population. Amnesty International has received testimony of gross human rights violations from hundreds of displaced persons in Chad, Darfur and in the capital, Khartoum. -

Country Report Sudan at a Glance: 2003-04

Country Report June 2003 Sudan Sudan at a glance: 2003-04 OVERVIEW The peace process between the government and the leading southern rebel force, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, will be kept alive by international pressure, although little of substance will be agreed in the short term. A ceasefire remains in effect until the end of June, while talks have been suspended until July. A US presidential report to Congress on the commitment of the Sudanese government to peace avoided calling for sanctions, signalling US support for ongoing dialogue. A significant rise in oil exports and a recovery in non-oil exports in 2003 are expected to ensure strong real GDP growth of 5.9%, slowing marginally to 5.3% in 2004. The current-account deficit, however, will widen over the forecast period to US$1.74bn by end-2004 (9.6% of GDP). Key changes from last month Political outlook • With halting progress in the peace talks, the political outlook is dependent upon the continued commitment to negotiations. Many obstacles remain, not least the role of the opposition groups not included in the talks and the growing unrest in the west of the country. Economic policy outlook • The government will not veer from its commitment to IMF-led policies, although expenditure may stray beyond agreed limits. Economic policy will continue to centre on balancing the budget through subsidy cutting and raising taxes. These measures, combined with a revised oil price forecast, will result in a reduced budget deficit of SD5.5bn (US$21.1m; 0.1% of GDP) in 2003, which will then widen in 2004 to SD33bn. -

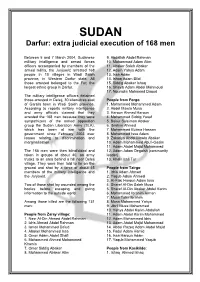

Darfur: Extra Judicial Execution of 168 Men

SUDAN Darfur: extra judicial execution of 168 men Between 5 and 7 March 2004, Sudanese 9. Abdallah Abdel Rahman military intelligence and armed forces 10. Mohammed Adam Atim officers accompanied by members of the 11. Abaker Saleh Abaker armed militia, the Janjawid, arrested 168 12. Adam Yahya Adam people in 10 villages in Wadi Saleh 13. Issa Adam province, in Western Darfur state. All 14. Ishaq Adam Bilal those arrested belonged to the Fur, the 15. Siddig Abaker Ishaq largest ethnic group in Darfur. 16. Shayib Adam Abdel Mahmoud 17. Nouradin Mohamed Daoud The military intelligence officers detained those arrested in Deleij, 30 kilometres east People from Forgo of Garsila town in Wadi Saleh province. 1. Mohammed Mohammed Adam According to reports military intelligence 2. Abdel Mawla Musa and army officials claimed that they 3. Haroun Ahmed Haroun arrested the 168 men because they were 4. Mohammed Siddig Yusuf sympathizers of the armed opposition 5. Bakur Suleiman Abaker group the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), 6. Ibrahim Ahmed which has been at war with the 7. Mohammed Burma Hassan government since February 2003 over 8. Mohammed Issa Adam issues relating to discrimination and 9. Zakariya Abdel Mawla Abaker marginalisation. 10. Adam Mohammed Abu’l-Gasim 11. Adam Abdel Majid Mohammed The 168 men were then blindfolded and 12. Adam Adam Degaish (community taken in groups of about 40, on army leader) trucks to an area behind a hill near Deleij 13. Khalil Issa Tur village. They were then told to lie on the ground and shot by a force of about 45 People from Tairgo members of the military intelligence and 1. -

Darfur Destroyed Ethnic Cleansing by Government and Militia Forces in Western Sudan Summary

Human Rights Watch May 2004 Vol. 16, No. 6(A) DARFUR DESTROYED ETHNIC CLEANSING BY GOVERNMENT AND MILITIA FORCES IN WESTERN SUDAN SUMMARY.................................................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 ABUSES BY THE GOVERNMENT-JANJAWEED IN WEST DARFUR.................... 7 Mass Killings By the Government and Janjaweed............................................................... 8 Attacks and massacres in Dar Masalit ............................................................................... 8 Mass Executions of captured Fur men in Wadi Salih: 145 killed................................ 21 Other Mass Killings of Fur civilians in Wadi Salih........................................................ 23 Aerial bombardment of civilians ..........................................................................................24 Systematic Targeting of Marsali and Fur, Burnings of Marsalit Villages and Destruction of Food Stocks and Other Essential Items ..................................................26 Destruction of Mosques and Islamic Religious Articles............................................... 27 Killings and assault accompanying looting of property....................................................28 Rape and other forms -

2002-04-07 ASSOCIATE PARLIAMENTARY GROUP On

ASSOCIATE PARLIAMENTARY GROUP ON SUDAN Visit to Sudan 7th - 12th April 2002 Facilitated by Christian Aid, Oxfam GB, Save the Children, Tearfund, and the British Embassy, Khartoum ASSOCIATE PARLIAMENTARY GROUP ON SUDAN Visit to Sudan 7th - 12th April 2002 Facilitated by Christian Aid, Oxfam GB, Save the Children, Tearfund, and the British Embassy, Khartoum Associate Parliamentary Group on Sudan 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We visited Sudan between April 6th and 13th 2002 under the auspices of the Associate Parliamentary Group for Sudan accompanied by HM Ambassador to Sudan Richard Makepeace, Dan Silvey of Christian Aid and the Group co-ordinator Colin Robertson. Our grateful thanks go to Colin and Dan for their superb organisation, tolerance and patience, to Christian Aid, Oxfam GB, Save the Children and Tearfund for their financial and logistical support, and to Ambassador Makepeace for his unfailing courtesy, deep knowledge of the current situation and crucial introductions. Our visit to southern Sudan could not have gone ahead without the hospitality and support of Susan from Unicef in Rumbek and Julie from Tearfund at Maluakon. As well as being grateful to them and their organisations we are enormously impressed by their courage and commitment to helping people in such difficult and challenging circumstances. Thanks to the efforts of these and many others we were able to pack a huge number of meetings and discussions into a few days, across several hundred miles of the largest country in Africa. The primary purpose of our visit was to listen and learn. Everyone talked to us of peace, and of their ideas about the sort of political settlement needed to ensure that such a peace would be sustainable, with every part of the country developed for the benefit of all of its people. -

Stop Violence Against Women

Lives blown apart Crimes against women in times of conflict Stop violence against women Amnesty International Publications First published in 2004 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom http://www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2004 ISBN: 0-86210-363-0 AI Index: ACT 77/075/2004 Original language: English Printed by: Alden Press, Oxford, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. This report would not have been possible without the help of many organizations and individuals who provided time, expertise and invaluable advice. In particular, Amnesty International would like to thank Tracy Ulltveit-Moe, research consultant. Cover photo : A woman carrying water to the village of Boeth in southern Sudan passes a pile of weapons belonging to rebel soldiers resting nearby, 2001 © Panos Pictures/Sven Torfinn Amnesty International is a worldwide movement of people who campaign for internationally recognized human rights to be respected and protected. Amnesty International’s vision is of a world in which every person enjoys all the human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. In pursuit of this vision, Amnesty International’s mission is to undertake research and action focused on preventing and ending grave abuses of the rights to physical and mental integrity, freedom of conscience and expression, and freedom from discrimination, within the context of its work to promote all human rights. -

Oil and Conflict in Sudan

Sudan Update - Raising the stakes - Oil and conflict in Sudan SUDAN UPDATE Raising the stakes: Oil and conflict in Sudan 1 Sudan Update - Raising the stakes - Oil and conflict in Sudan Reports: Oil Raising the stakes: Oil and conflict in Sudan 1 - Introduction OIL BOOM? On 30 August 1999, Sudan filled its first tanker-load of oil. A gigantic pipeline snaking up from oilfields over 1600 kilometres into the African hinterland was at last disgorging 100,000 barrels a day of crude oil at a nearly-completed marine terminal near Port Sudan, on the Red Sea. It offered fulfilment of countless promises of oil wealth that had been repeated to the Sudanese people by their rulers over the last quarter of a century. Billions of dollars had been invested, first in exploration, then pipeline, refinery and terminal construction. Now Sudan, Africa's largest country, could join OPEC and hold its head up as an oil exporter alongside Saudi Arabia and Libya, said Sudan's government ministers. Their critics replied that if it did join OPEC it would be politically insignificant alongside the major producers. Better parallels would be with the repression, sabotage, corruption and pollution encountered in Burma, Colombia or the Niger Delta. Just three weeks later, on 20 September 1999, opponents of Sudan's military regime blew a hole in the newly-completed pipeline. The explosion took place just outside the town of Atbara, the centre of Sudan's railway industry, on the river Nile above Khartoum. The location is important because - if one believed the oil companies or the government - it was so unlikely. -

S/2020/614 Security Council

United Nations S/2020/614 Security Council Distr.: General 29 June 2020 Original: English Children and armed conflict in the Sudan Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions on children and armed conflict, is the sixth report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Sudan. It focuses on trends in and patterns of violations committed against children in Darfur, the Two Areas and Abyei between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2019. It provides information on the perpetrators of the violations, as well as on actions taken by the parties to the conflict to improve the protection of children affected by armed conflict, including dialogue and actions plans. The report also contains a series of recommendations aimed at ending and preventing grave violations against children in the Sudan. 20-08611 (E) 210720 *2008611* S/2020/614 I. Introduction 1. The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions on children and armed conflict, is the sixth report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Sudan and covers the period from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2019. It contains descriptions of the trends in grave violations committed against children since the previous report (S/2017/191) and outlines the progress and challenges since the adoption of the conclusions by the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict in July 2017 (S/AC.51/2017/3). The violations presented in the report have been verified by the country task force on monitoring and reporting, co-chaired by the African Union- United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) for Darfur, and the Resident Coordinator and UNICEF for the Two Areas (Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile) and Abyei. -

America's Secret Migs

THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE SECRET COLD WAR TRAINING PROGRAM RED EAGLES America’s Secret MiGs STEVE DAVIES FOREWORD BY GENERAL J. JUMPER © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com RED EAGLES America’s Secret MiGs OSPREY PUBLISHING © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS DEDICATION 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 FOREWORD 10 INTRODUCTION 12 PART 1 ACQUIRING “THE ASSETS” 15 Chapter 1: HAVE MiGs, 1968–69 16 Chapter 2: A Genesis for the Red Eagles, 1972–77 21 PART 2 LAYING THE GROUND WORK 49 Chapter 3: CONSTANT PEG and Tonopah, 1977–79 50 Chapter 4: The Red Eagles’ First Days and the Early MiGs 78 Chapter 5: The “Flogger” Arrives, 1980 126 Chapter 6: Gold Wings, 1981 138 PART 3 EXPANDED EXPOSURES AND RED FLAG, 1982–85 155 Chapter 7: The Fatalists, 1982 156 Chapter 8: Postai’s Crash 176 Chapter 9: Exposing the TAF, 1983 193 Chapter 10: “The Air Force is Coming,” 1984 221 Chapter 11: From Black to Gray, 1985 256 PART 4 THE FINAL YEARS, 1986–88 275 Chapter 12: Increasing Blue Air Exposures, 1986 276 Chapter 13: “Red Country,” 1987 293 Chapter 14: Arrival Shows, 1988 318 POSTSCRIPT 327 ENDNOTES 330 APPENDICES 334 GLOSSARY 342 INDEX 346 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com DEDICATION In memory of LtCdr Hugh “Bandit” Brown and Capt Mark “Toast” Postai — 6 — © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is a story about the Red Eagles: a group of men, and a handful of women, who provided America’s fighter pilots with a level of training that was the stuff of dreams. It was codenamed CONSTANT PEG. -

Human Rights Abuses in Sudan Over the Month of May 20161 Overview

Human Rights Abuses in Sudan over the Month of May 20161 Overview During the month of May 2016, SUDO (UK)’s network of human rights monitors have reported and verified 75 incidents of human rights abuses across Sudan involving eight Sudanese states. Enclosed within the 75 reports pertaining to human rights abuses, SUDO (UK) has assessed that various forces under the direct authority of the Government of Sudan2 were responsible, as individual entities, for 41 instances of human rights abuses. A further 14 abuses were carried out by groups categorised by monitors as “pro-government militias”3, whilst 17 such abuses were recorded against militias labelled as Janjaweed. Three human rights abuses were perpetrated by the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – North (SPLM-N), and one abuse was registered against the following entities: a Salamat ethnic militia; the SPLM-Peace Wing headed by Daniel Kodi; and an unknown actor. It is worth stressing that at times multiple actors colluded in any one instance, hence why 78 perpetrators have been identified for 75 incidents. The 75 reports detail the following: the death of 33 civilians4 including 10 children; the serious injury of 87 civilians; the rape of 22 women including five minors (this number does not include the as yet unconfirmed reports of dozens of women raped in an incident recorded in South Darfur); the arrest of 35 civilians (two of which were subject to beatings, whilst another has been subject to rape alongside 12 detained women in Blue Nile); 45 counts of kidnap; five incidents of aerial bombardment utilising a minimum of 31 bombs including explosive bombs; eight direct attacks on civilian villages and/or towns; and 10 incidents pertaining to press freedom including six newspaper confiscations.