Stop Violence Against Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture | the AHRC Cultural Value

Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska 2 Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska THE AHRC CULTURAL VALUE PROJECT CONTENTS Foreword 3 4. The engaged citizen: civic agency 58 & civic engagement Executive summary 6 Preconditions for political engagement 59 Civic space and civic engagement: three case studies 61 Part 1 Introduction Creative challenge: cultural industries, digging 63 and climate change 1. Rethinking the terms of the cultural 12 Culture, conflict and post-conflict: 66 value debate a double-edged sword? The Cultural Value Project 12 Culture and art: a brief intellectual history 14 5. Communities, Regeneration and Space 71 Cultural policy and the many lives of cultural value 16 Place, identity and public art 71 Beyond dichotomies: the view from 19 Urban regeneration 74 Cultural Value Project awards Creative places, creative quarters 77 Prioritising experience and methodological diversity 21 Community arts 81 Coda: arts, culture and rural communities 83 2. Cross-cutting themes 25 Modes of cultural engagement 25 6. Economy: impact, innovation and ecology 86 Arts and culture in an unequal society 29 The economic benefits of what? 87 Digital transformations 34 Ways of counting 89 Wellbeing and capabilities 37 Agglomeration and attractiveness 91 The innovation economy 92 Part 2 Components of Cultural Value Ecologies of culture 95 3. The reflective individual 42 7. Health, ageing and wellbeing 100 Cultural engagement and the self 43 Therapeutic, clinical and environmental 101 Case study: arts, culture and the criminal 47 interventions justice system Community-based arts and health 104 Cultural engagement and the other 49 Longer-term health benefits and subjective 106 Case study: professional and informal carers 51 wellbeing Culture and international influence 54 Ageing and dementia 108 Two cultures? 110 8. -

Négociations Fondation Maeght : Entre Célébrations Monaco - Union Européenne Et Polémique R 28240 - F : 2,50 € Michel Roger S’Explique

FOOT : SANS FALCAO ET JAMES, QUELLES AMBITIONS POUR L’ASM ? 2,50 € Numéro 135 - Septembre 2014 - www.lobservateurdemonaco.mc SOCIÉTÉ USINE D’INCINÉRATION : LES SCÉNARIOS POSSIBLES ECOLOGIE CHANGEMENT CLIMATIQUE : POURQUOI IL FAUT RÉAGIR CULTURE NÉGOCIATIONS FONDATION MAEGHT : ENTRE CÉLÉBRATIONS MONACO - UNION EUROPÉENNE ET POLÉMIQUE R 28240 - F : 2,50 € MICHEL ROGER S’EXPLIQUE 3 782824 002503 01350 pour lui Solavie pag Observateur 09/2014.indd 2 08/09/14 15:51 LA PHOTO DU MOIS CRAINTES epuis des mois, dans certains milieux, on ne parle que de ça. En principauté, le lancement des négociations avec l’Union européenne (UE) inquiète pas mal de monde. Notamment les professions libérales qui craignent Dde voir tomber le presque total monopole qu’ont les Monégasques sur ces professions très encadrées réglementairement. « Ceci entraînerait à très court terme la disparition de notre profession telle qu’elle existe depuis des siècles. Ce qui est très préoccupant. D’autant plus que ce sera la même chose pour les médecins, les architectes, les experts-comptables monégasques… », a expliqué à L’Obs’ le bâtonnier de l’ordre des avocats de Monaco, Me Richard Mullot. Une crainte qui a poussé les avocats, les dentistes, les médecins et les architectes à se réunir pour réfléchir à la création d’un collectif. Objectif : défendre auprès du gou- vernement leurs positions et leurs spécificités qui restent propres à chaque profession. En face, le gouvernement cherche à rassurer. Dans l’interview qu’il a accordée à L’Obs’, le ministre d’Etat, Michel Roger, le répète. Il est hors de ques - tion de brader ce qui a fait le succès de la princi- pauté : « Il n’y aura pas d’accord si Monaco devait perdre sa souveraineté ou si ses spécificités devaient être menacées. -

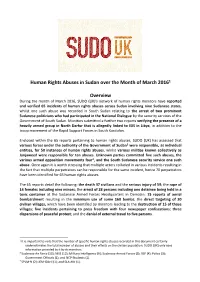

Human Rights Abuses in Sudan Over the Month of March 20161 Overview

Human Rights Abuses in Sudan over the Month of March 20161 Overview During the month of March 2016, SUDO (UK)’s network of human rights monitors have reported and verified 65 incidents of human rights abuses across Sudan involving nine Sudanese states, whilst one such abuse was recorded in South Sudan relating to the arrest of two prominent Sudanese politicians who had participated in the National Dialogue by the security services of the Government of South Sudan. Monitors submitted a further two reports verifying the presence of a heavily armed group in North Darfur that is allegedly linked to ISIS in Libya, in addition to the troop movement of the Rapid Support Forces in South Kordofan. Enclosed within the 65 reports pertaining to human rights abuses, SUDO (UK) has assessed that various forces under the authority of the Government of Sudan2 were responsible, as individual entities, for 50 instances of human rights abuses, whilst various militias known collectively as Janjaweed were responsible for ten abuses. Unknown parties committed five such abuses, the various armed opposition movements four3, and the South Sudanese security service one such abuse. Once again it is worth stressing that multiple actors colluded in various incidents resulting in the fact that multiple perpetrators can be responsible for the same incident, hence 70 perpetrators have been identified for 65 human rights abuses. The 65 reports detail the following: the death 37 civilians and the serious injury of 59; the rape of 14 females including nine minors; the arrest of 28 persons including one detainee being held in a toxic container at the Sudanese Armed Forces Headquarters in Demazin; 15 reports of aerial bombardment resulting in the minimum use of some 160 bombs; the direct targeting of 30 civilian villages, which have been identified by monitors leading to the destruction of 15 of those villages; five incidents pertaining to press freedom with four newspaper confiscations; three dispersions of peaceful protest; and the denial of external travel to five persons. -

Culture and Conflict Summit Draft Resource Guide

Culture and Conflict Summit Draft Resource Guide September 10 and 11, 2014 Washington, DC About the Resource Guide This resource guide is a beginning of a comprehensive resource for educators and peacebuilders interested in using arts both inside and outside academia. It is meant to be a useful guide to those who are teaching about using arts in conflict scenarios for the purposes of peace, and those who will engage in it in practice. We encourage you to reflect on additional resources that would be useful for these groups of people during the two days of the Culture and Conflict Summit, hosted by the British Council in partnership with the U.S. Institute of Peace. We also encourage critical feedback on the current draft resource guide to increase its utility for those working for peace. 2 The United States Institute of Peace [USIP] is an independent, nonpartisan conflict management center created by the United States Congress thirty years ago. Our mission is to prevent, mitigate, and resolve violent conflicts around the world. We do this by engaging directly in conflict zones and providing analysis, education, and resources to those working for peace. Our work in conflict zones has revealed to us that arts and culture are powerful tools to educate societies about alternatives to violence and mobilize people to undertake nonviolent action to challenge injustices and advance a sustainable peace. We know that every society has cultural reservoirs that can be tapped to advance counter- narratives focused on the nonviolent transformation of conflict. This should be an integral part of strengthening individuals and institutions working for peace. -

Legacy – the All Blacks

LEGACY WHAT THE ALL BLACKS CAN TEACH US ABOUT THE BUSINESS OF LIFE LEGACY 15 LESSONS IN LEADERSHIP JAMES KERR Constable • London Constable & Robinson Ltd 55-56 Russell Square London WC1B 4HP www.constablerobinson.com First published in the UK by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2013 Copyright © James Kerr, 2013 Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologise for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition. The right of James Kerr to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-47210-353-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-47210-490-8 (ebook) Printed and bound in the UK 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Cover design: www.aesopagency.com The Challenge When the opposition line up against the New Zealand national rugby team – the All Blacks – they face the haka, the highly ritualized challenge thrown down by one group of warriors to another. -

White Paper for a Sustainable Peace in Casamance

White Paper for a Sustainable Peace in Casamance Perspectives from Women and Local Populations August 2019 Content 3. Acronyms & Abbreviations 4. Acknowledgements 5. Foreword 7. Cry For Action Of The Women Of Casamance! 8. Preface 9. Introduction 9. Context 11. Historical background of the conflict and the peace process 13. The Conflict’s Impacts On Local Populations, Women And Youth 13. Socioeconomic and environmental impacts 15. Casamance populations’ perceptions and feelings of exclusion 17. The conflict’s specific impacts on women 18. A permanent insecurity 19. Strategies And Perspectives From Civil Society 20. Civil society actors 21. Addressing challenges and establishing peace 23. Actions and approaches 25. Conditions for effective and inclusive participation 26. Women’s participation in peace processes 26. The mediation role of women of Casamance 27. La Plateforme des Femmes pour la Paix en Casamance (PFPC) 28. Senegambia Forum 29. Breaking down barriers and strengthening support across women throughout Senegal 30. Recommendations for a definitive & sustainable peace in Casamance 34. Bibliography 35. Annexes 49. Endnotes Acronyms & Abbreviations AFUDES Association of United Brothers for the Economic and Social Development of the Fogny ASC Sports and Cultural Association AJAEDO Association des Jeunes Agriculteurs et Éleveurs du Département d'Oussouye AJWS American Jewish World Service (NGO) ANRAC Agence nationale pour la Relance des Activités économiques en Casamance ANSD Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie -

Violent Conflicts and Civil Strife in West Africa: Causes, Stability Challenges and Prospects

Annan, N 2014 Violent Conflicts and Civil Strife in West Africa: Causes, stability Challenges and Prospects. Stability: International Journal of Security & Development, 3(1): 3, pp. 1-16, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/sta.da RESEARCH ARTICLE Violent Conflicts and Civil Strife in West Africa: Causes, Challenges and Prospects Nancy Annan* The advent of intra-state conflicts or ‘new wars’ in West Africa has brought many of its economies to the brink of collapse, creating humanitarian casualties and concerns. For decades, countries such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea- Bissau were crippled by conflicts and civil strife in which violence and incessant killings were prevalent. While violent conflicts are declining in the sub-region, recent insurgencies in the Sahel region affecting the West African countries of Mali, Niger and Mauritania and low intensity conflicts surging within notably stable countries such as Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal sends alarming signals of the possible re-surfacing of internal and regional violent conflicts. These conflicts are often hinged on several factors including poverty, human rights violations, bad governance and corruption, ethnic marginalization and small arms proliferation. Although many actors including the ECOWAS, civil society and international community have been making efforts, conflicts continue to persist in the sub-region and their resolution is often protracted. This paper posits that the poor understanding of the fundamental causes of West Africa’s violent conflicts and civil strife would likely cause the sub-region to continue experiencing and suffering the brunt of these violent wars. Introduction 24). While violent conflicts are declining in The transformation from inter-state to intra- the sub-region, recent insurgencies in the state conflict from the latter part of the 20th Sahel region affecting the West African coun- Century in West Africa brought a number of tries of Mali, Niger and Mauritania sends its economies to near collapse. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations. -

Sudan Arming the Perpetrators of Grave Abuses in Darfur

Sudan Arming the perpetrators of grave abuses in Darfur Map The boundary between north and south Sudan runs south of Southern Darfur, Western Kordofan, Southern Kordofan, White Nile and Blue Nile States. The so-called 'marginal' areas are Abyei, Southern Kordofan/the Nuba mountains and Blue Nile State. Introduction "I was living with my family in Tawila and going to school when one day the Janjawid came and attacked the school. We all tried to leave the school but we heard noises of bombing and started running in all directions... The Janjawid caught some girls: I was raped by four men inside the school…When I went back to town, I found that they had destroyed all the buildings. Two planes and a helicopter had bombed the town. One of my uncles and a cousin were killed in the attack. " A 19- year-old woman, describing the attack on Tawila in February 2004.(1) Governments of countries named in this report that have allowed the supply of various types of arms to Sudan over the past few years have contributed to the capacity of Sudanese leaders to use their army and air force to carry out grave violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. Foreign governments have also enabled the government of Sudan to arm and deploy untrained and unaccountable militias that have deliberately and indiscriminately killed civilians in Darfur on a large scale, destroying homes, looting property and forcibly displacing the population. Amnesty International has received testimony of gross human rights violations from hundreds of displaced persons in Chad, Darfur and in the capital, Khartoum. -

Accessing Services in the City the Significance of Urban Refugee-Host Relations in Cameroon, Indonesia and Pakistan

ACCESSING SERVICES IN THE CITY THE SIGNIFICANCE OF URBAN REFUGEE-HOST RELATIONS IN CAMEROON, INDONESIA AND PAKISTAN CHURCH WORLD SERVICE FEBRUARY 2013 Graeme Rodgers/CWS ACCESSING SERVICES IN THE CITY THE SIGNIFICANCE OF URBAN REFUGEE-HOST RELATIONS IN CAMEROON, INDONESIA AND PAKISTAN Church World Service, New York Immigration and Refugee Program February 2013 Executive Summary This report considers how relationships between urban refugees and more established local communities affect refugee access to key services and resources. According to the estimates of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the majority of the world’s refugees now reside in cities or towns. In contrast to camps, where refugees are relatively isolated from local host communities and more dependent on assistance from humanitarian agencies to meet their basic needs, refugees in urban areas typically depend more on social networks, relationships and individual agency to re-establish their livelihoods. This study explores the conditions under which refugee-host relations may either promote or inhibit refugee access to local services and other resources. It also considers how positive impacts of these evolving relationships may be nurtured and developed to improve humanitarian outcomes for refugees. In 2009, UNHCR updated its policy on refugees in urban areas, highlighting the challenges of providing protection and assistance in spatially and socially complex environments. This initiative has encouraged the broader humanitarian community to explore more innovative approaches to understanding and programming related to refugees in urban areas. One of the effects of this development has been to highlight the role of the host community and the importance of considering their needs and perspectives. -

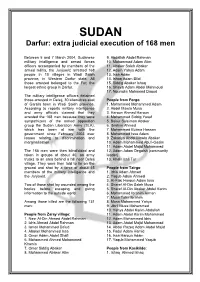

Darfur: Extra Judicial Execution of 168 Men

SUDAN Darfur: extra judicial execution of 168 men Between 5 and 7 March 2004, Sudanese 9. Abdallah Abdel Rahman military intelligence and armed forces 10. Mohammed Adam Atim officers accompanied by members of the 11. Abaker Saleh Abaker armed militia, the Janjawid, arrested 168 12. Adam Yahya Adam people in 10 villages in Wadi Saleh 13. Issa Adam province, in Western Darfur state. All 14. Ishaq Adam Bilal those arrested belonged to the Fur, the 15. Siddig Abaker Ishaq largest ethnic group in Darfur. 16. Shayib Adam Abdel Mahmoud 17. Nouradin Mohamed Daoud The military intelligence officers detained those arrested in Deleij, 30 kilometres east People from Forgo of Garsila town in Wadi Saleh province. 1. Mohammed Mohammed Adam According to reports military intelligence 2. Abdel Mawla Musa and army officials claimed that they 3. Haroun Ahmed Haroun arrested the 168 men because they were 4. Mohammed Siddig Yusuf sympathizers of the armed opposition 5. Bakur Suleiman Abaker group the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), 6. Ibrahim Ahmed which has been at war with the 7. Mohammed Burma Hassan government since February 2003 over 8. Mohammed Issa Adam issues relating to discrimination and 9. Zakariya Abdel Mawla Abaker marginalisation. 10. Adam Mohammed Abu’l-Gasim 11. Adam Abdel Majid Mohammed The 168 men were then blindfolded and 12. Adam Adam Degaish (community taken in groups of about 40, on army leader) trucks to an area behind a hill near Deleij 13. Khalil Issa Tur village. They were then told to lie on the ground and shot by a force of about 45 People from Tairgo members of the military intelligence and 1. -

Darfur Destroyed Ethnic Cleansing by Government and Militia Forces in Western Sudan Summary

Human Rights Watch May 2004 Vol. 16, No. 6(A) DARFUR DESTROYED ETHNIC CLEANSING BY GOVERNMENT AND MILITIA FORCES IN WESTERN SUDAN SUMMARY.................................................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 ABUSES BY THE GOVERNMENT-JANJAWEED IN WEST DARFUR.................... 7 Mass Killings By the Government and Janjaweed............................................................... 8 Attacks and massacres in Dar Masalit ............................................................................... 8 Mass Executions of captured Fur men in Wadi Salih: 145 killed................................ 21 Other Mass Killings of Fur civilians in Wadi Salih........................................................ 23 Aerial bombardment of civilians ..........................................................................................24 Systematic Targeting of Marsali and Fur, Burnings of Marsalit Villages and Destruction of Food Stocks and Other Essential Items ..................................................26 Destruction of Mosques and Islamic Religious Articles............................................... 27 Killings and assault accompanying looting of property....................................................28 Rape and other forms