Gould Piano Trio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Zurich Chamber Orchestra EDMOND DE STOUTZ, Conductor

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN The Zurich Chamber Orchestra EDMOND DE STOUTZ, Conductor FRIDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 15, 1980, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Symphony No. 3 in C major ........... BOYCE Allegro Vivace Tempo di menuetto Suite about the Present Times for Two String Orchestras (1979) . MORET Pourquoi Ombre vansante du songe Abime Extase Aux quatre vents Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major ........ BACH Allegro, adagio Allegro INTERMISSION Apollon Musagete ............. STRAVINSKY Naissance d'ApoIIon Variation Terpsichore Variation d'Apollon Variation d'Apollon Pas d'action Pas de deux Variation de calliope Coda Variation de polymnie Apotheose Concertino No. 2 in G major .......... PERGOLESI Largo Da cappella Largo affettuoso Allegro Angel, Columbia, and Turnabout Records. 101st Season Forty-eighth Concert Seventeenth Annual Chamber Arts Series PROGRAM NOTES Symphony No. 3 in C major ......... WILLIAM BOYCE (1711-1779) By the time his symphonies were published (1760), Dr. William Boyce had attained a position of eminence and honor among English musicians. He held the post of Composer to the Royal Chapel, and he was also one of the Chapel's organists. Receiving his doctorate in music at Cambridge, he then took office as Master of the King's Music (1755-1759). His reverence for the old masters of English church music, which was encouraged by his teacher Maurice Greene, resulted in his completing Greene's projected collection of English Cathedral Music, the first volume of which was published in 1760. Vocal music was considered by most composers to be of paramount importance "the finest instrumental music" being regarded as "an imitation of the vocal." It is not therefore surprising that some instrumental forms originated as introductions and adornments to vocal works. -

24 August 2021

24 August 2021 12:01 AM Bruno Bjelinski (1909-1992) Concerto da primavera (1978) Tonko Ninic (violin), Zagreb Soloists HRHRTR 12:11 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Piano Sonata in C major K.545 Young-Lan Han (piano) KRKBS 12:21 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) 3 Songs for chorus, Op 42 Danish National Radio Choir, Stefan Parkman (conductor) DKDR 12:32 AM Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824) Serenade for 2 violins in A major, Op 23 no 1 Angel Stankov (violin), Yossif Radionov (violin) BGBNR 12:41 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809),Ignace Joseph Pleyel (1757-1831), Harold Perry (arranger) Divertimento 'Feldpartita' in B flat major, Hob.2.46 Academic Wind Quintet BGBNR 12:50 AM Joaquin Nin (1879-1949) Seguida Espanola Henry-David Varema (cello), Heiki Matlik (guitar) EEER 12:59 AM Toivo Kuula (1883-1918) 3 Satukuvaa (Fairy-tale pictures) for piano (Op.19) Juhani Lagerspetz (piano) FIYLE 01:15 AM Edmund Rubbra (1901-1986) Trio in one movement, Op 68 Hertz Trio CACBC 01:35 AM Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) Peer Gynt - Suite No 1 Op 46 Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Ole Kristian Ruud (conductor) NONRK 02:01 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Metamorphosen Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, Giordano Bellincampi (conductor) NZRNZ 02:28 AM Max Bruch (1838-1920) Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 26 James Ehnes (violin), Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, Giordano Bellincampi (conductor) NZRNZ 02:52 AM Eugene Ysaye (1858-1931) Sonata for Solo Violin in D minor, op. 27/3 James Ehnes (violin) NZRNZ 02:59 AM Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Symphony No. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

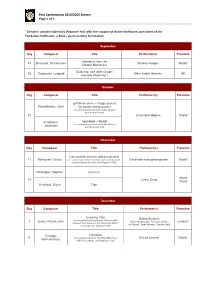

Past Commissions 2014/15

Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 1 of 5 * Denotes commissioned by Wigmore Hall with the support of André Hoffmann, president of the Fondation Hoffmann, a Swiss grant-making foundation September Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Variations from the 14 Birtwistle, Sir Harrison Nicolas Hodges World* Golden Mountains Study No. 44A after Chopin 15 Godowsky, Leopold Marc-André Hamelin UK nouvelle étude No.1 October Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première gefährlich dünn — fragile pieces Petraškevičs, Jānis for double string quartet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern and Wigmore Hall) 10 Ensemble Modern World* Schöllhorn, sous-bois – Sextet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern Johannes and Wigmore Hall) November Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Carnaval for clarinet, piano and cello 11 Mantovani, Bruno (co-commissioned by Ensemble intercontemporain, Ensemble intercontemporain World* Opéra national de Paris and Wigmore Hall) Montague, Stephen nun-mul World 16 Jenna Sung World Pritchard, Gwyn Tide December Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Uncanny Vale Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 3 Jones, Patrick John (Emer McDonough, Nicholas Daniel, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted Joy Farrall, Sarah Burnett, Stephen Bell) campaign and Wigmore Hall) Turnage, Contusion 6 (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, Belcea Quartet World* Mark-Anthony NMC Recordings and Wigmore Hall) Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 2 of 5 January Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Light and Matter Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 14 Saariaho, Kaija (Jacqueline Shave, Caroline Dearnley, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted campaign Huw Watkins) and Wigmore Hall) 3rd Quartet Holt, Simon (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, World* NMC Recordings, Heidelberger Frühling, and 19 Wigmore Hall) JACK Quartet Haas, Georg Friedrich String Quartet No. -

Download the Job Description

MUSIC. THEATRE. WALES. needs a Marketing and Communications Manager Fixed term contract until the end of December 2020 (part-time) We are inviting applications from suitably qualified candidates who are able to offer 3 days a week. The company is based in an attractive, modern office situated within a listed building close to Cardiff Bay station and the successful candidate will be expected to work from here. Salary: £27-30k depending on experience (pro rata) Music Theatre Wales is one of Europe’s leading contemporary opera companies, recognised since its formation in 1988 as a vital force in opera, presenting bold new work that is characterised by the powerful impact it makes on audiences and artists alike. We work in association with the UK’s leading contemporary music ensemble, the London Sinfonietta, with whom all our productions are performed. In 2020, we will deliver two contrasting new works: February/March 2020 • Denis & Katya by Philip Venables and Ted Huffman has already proved to be an outstanding success with our co-producers at Opera Philadelphia where the work has been acclaimed as a totally new way of using opera and music theatre to engage with current social issues. Alongside this, we will run a Young People’s Consultation and Creative Project aimed at hard-to-reach young people in Newport and Mold. June/July and Autumn 2020 • Violet will be an equally powerful contemporary work which presents a female- centred plot that stands in stark contrast to most of the operatic canon. Composed by Tom Coult and written by Alice Birch – an outstanding and uncompromising theatre writer known for her strong females leads – Violet will give award-winning theatre director Rebecca Frecknall the chance to work in opera for the first time. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

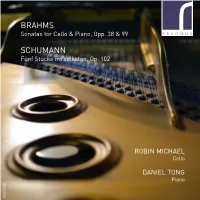

Brahms Schumann

BRAHMS Sonatas for Cello & Piano, Opp. 38 & 99 SCHUMANN Fünf Stücke im Volkston, Op. 102 ROBIN MICHAEL Cello DANIEL TONG Piano RES10188 Brahms & Schumann Works for Cello & Piano Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Sonata No. 1 for Cello and Piano in E minor, Op. 38 1. Allegro non troppo [13:26] 2. Allegretto quasi menuetto [5:37] Robin Michael cello 3. Allegro [6:23] Daniel Tong piano Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Fünf Stücke im Volkston, Op. 102 Cello by Stephan von Baehr (Paris, 2010), after Matteo Goffriller (1695) (Five Pieces in Folk Style) Bow by Noel Burke (Ireland, 2012), after François Xavier Tourte (1820) 4. Vanitas vanitatum [2:57] 5. Langsam [3:24] Blüthner Boudoir Grand Piano thought to have been played and 6. Nicht schnell, mit viel Ton zu spielen [3:56] selected by Brahms, Serial No. 45615 (1897) 7. Nicht zu rasch [1:54] 8. Stark und markiert [3:08] Johannes Brahms Sonata No. 2 for Cello and Piano in F major, Op. 99 9. Allegro vivace [8:51] 10. Adagio affettuoso [6:21] 11. Allegro passionato [6:51] 12. Allegro molto [4:41] About Robin Michael: Total playing time [67:35] ‘Michael played with fervour, graceful finesse and great sensitivity’ The Strad About Daniel Tong: ‘[...] it’s always a blessed relief to hear an artist with Daniel Tong’s self-evident love and understanding of the instrument’ BBC Music Magazine Brahms & Schumann: inventiveness and in its firm but delicately Works for Cello & Piano detailed structure.’ The first copies of the published sonata appeared in August 1866, Brahms started work on his Cello Sonata No. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

NMC164 Watkins-Wyas-Booklet

Huw Watkins In my craft or sullen art Mark Padmore tenor Huw Watkins piano Paul Watkins cello Alina Ibragimova violin The Nash Ensemble Elias Quartet Huw Watkins Sonata for Cello and Three Auden Songs 8’47 The Nash Ensemble Eight Instruments 13’44 10 Brussels in Winter 3’31 Artistic Director Amelia Freedman CBE FRAM 1 Allegro 4’36 11 Eyes look into the well 2’51 Paul Watkins cello 2 Lento 5’04 12 At last the secret is out 2’25 Ian Brown conductor 3 Allegro 4’04 Mark Padmore tenor Philippa Davies flute Paul Watkins cello Huw Watkins piano Richard Hosford clarinet The Nash Ensemble Ursula Leveaux bassoon Laura Samuel violin Ian Brown conductor 15’02 Partita for solo violin Catherine Leonard violin 13 Maestoso 4’07 Lawrence Power viola Four Spencer Pieces 15’15 14 Lento ma non troppo 1’06 Duncan McTier double bass 4 Prelude 1’46 15 Lento 4’31 and Huw Watkins piano 5 Shipbuilding on the Clyde 1’49 16 Comodo 1’04 6 The Crucifixion 1’36 17 Allegro molto 4’14 Elias Quartet 7 The Resurrection of Soldiers 5’51 Alina Ibragimova violin Sara Bitlloch violin Separating Fighting Swans 2’28 8 Donald Grant violin 9 Postlude 1’45 18 In my craft or sullen art: Martin Saving viola Marie Bitlloch cello Huw Watkins piano Goodison Quartet No 4 17’31 Mark Padmore tenor Elias Quartet Total timing 71’01 Mark Padmore appears by arrangement with Harmonia Mundi USA. Alina Ibragimova appears on this recording with kind permission from Hyperion Records. -

The Four Seasons I

27 Season 2013-2014 Friday, November 29, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, November 30, at 8:00 Sunday, December 1, at 2:00 Richard Egarr Conductor and Harpsichord Giuliano Carmignola Violin Vivaldi The Four Seasons I. Spring, Concerto in E major, RV 269 a. Allegro b. Largo c. Allegro II. Summer, Concerto in G minor, RV 315 a. Allegro non molto b. Adagio alternating with Presto c. Presto III. Autumn, Concerto in F major, RV 293 a. Allegro b. Adagio molto c. Allegro IV. Winter, Concerto in F minor, RV 297 a. Allegro non molto b. Largo c. Allegro Intermission 28 Purcell Suite No. 1 from The Fairy Queen I. Prelude II. Rondeau III. Jig IV. Hornpipe V. Dance for the Fairies Haydn Symphony No. 101 in D major (“The Clock”) I. Adagio—Presto II. Andante III. Menuetto (Allegretto)—Trio—Menuetto da capo IV. Vivace This program runs approximately 1 hour, 40 minutes. The November 29 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 3 Story Title 29 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra community itself. His concerts to perform in China, in 1973 is one of the preeminent of diverse repertoire attract at the request of President orchestras in the world, sold-out houses, and he has Nixon, today The Philadelphia renowned for its distinctive established a regular forum Orchestra boasts a new sound, desired for its for connecting with concert- partnership with the National keen ability to capture the goers through Post-Concert Centre for the Performing hearts and imaginations of Conversations. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1.