Brahms Schumann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

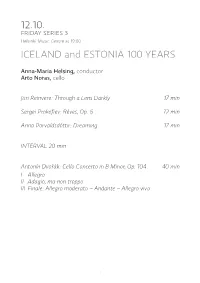

12.10. ICELAND and ESTONIA 100 YEARS

12.10. FRIDAY SERIES 3 Helsinki Music Centre at 19:00 ICELAND and ESTONIA 100 YEARS Anna-Maria Helsing, conductor Arto Noras, cello Jüri Reinvere: Through a Lens Darkly 17 min Sergei Prokofiev: Rêves, Op. 6 12 min Anna Þorvaldsdóttir: Dreaming 17 min INTERVAL 20 min Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 40 min I Allegro II Adagio, ma non troppo III Finale: Allegro moderato – Andante – Allegro vivo 1 The LATE-NIGHT CHAMBER MUSIC will begin in the main Concert Hall after an interval of about 10 minutes. Those attending are asked to take (unnumbered) seats in the stalls. Paula Sundqvist, violin Tuija Rantamäki, cello Sonja Fräki, piano Antonín Dvořák: Piano Trio “Dumky” 31 min 1. Lento maestoso – Allegro vivace – Allegro molto 2. Poco adagio – Vivace 3. Andante – Vivace non troppo 4. Andante moderato – Allegretto scherzando – Allegro 5. Allegro 6. Lento maestoso – Vivace Interval at about 20:00. The concert will end at about 21:15, the late-night chamber music at about 22:00. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and Yle Areena. It will also be shown in two parts in the programme “RSO Musiikkitalossa” (The FRSO at the Helsinki Music Centre) on Yle Teema on 21.10. and 4.11., with a repeat on Yle TV 1 on 27.10. and 10.11. 2 JÜRI REINVERE director became a close friend and im- portant mentor of the young compos- (b. 1971): THROUGH A er. Theirs was not simply a master-ap- LENS DARKLY prenticeship relationship, for they often talked about music, and Reinvere would Jüri Reinvere has been described as a sometimes express his own views as a true cosmopolitan with Estonian roots. -

Double Bass Sound Christine Hoock

MOZARTEUM DOUBLE BASS SOUND CHRISTINE HOOCK RECORDS MOZARTEUM DOUBLE BASS SOUND – Christine Hoock Die CD-Reihe „Mozarteum-Sound“ hat es sich ten und Studierenden ihrer Klasse im Fokus dieser zum Ziel gesetzt, hervorragende künstlerische Aufnahme. Als Partner standen ihr bei der Reali- Leistungen wie auch eine besondere Klangästhetik sierung dieses breitgefächerten Repertoires Hans- – immer in Bezug auf ein bestimmtes Instrument jörg Angerer (Chefdirigent der Bläserphilharmonie – an der Universität Mozarteum Salzburg zu do- Mozarteum Salzburg), Benjamin Schmid (Violine), kumentieren. Mari Kato (Klavier), Ariane Haering (Klavier), Bar- bara Nussbaum (Klavier) und DJ UmbertoEcho (Mi- Diesmal dem Kontrabass mit seiner außerordent- xing Desk) zur Seite. lichen Beweglichkeit, seinem Farbenreichtum und seiner Virtuosität – dabei oft nahezu archaische Klangwelten erschaffend – gewidmet, steht die au- ßergewöhnliche Kontrabass-Künstlerin Christine Hoock gemeinsam mit Absolventinnen/Absolven- MOZARTEUM DOUBLE BASS SOUND – Christine Hoock The CD series Mozarteum Sound aims to docu- the Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg), ment excellent artistic achievements at the Moz- Benjamin Schmid (violin), Mari Kato (piano), Ariane arteum University as well as a particular kind of Haering (piano), Barbara Nussbaum (piano) and aesthetic sound, always related to a certain in- DJ UmbertoEcho (mixing desk). strument. This recording is devoted to the double bass and reveals its extraordinary fl exibility, rich colours and virtuosity, and features the outstanding double bass player Christine Hoock, together with graduates and students from her class. Partners in the realization of this broad repertoire were Hansjörg Angerer (principal conductor of 1 1 CHRISTINE HOOCK „... jeder entscheidet sich intuitiv für das Instru- Dies spiegelt sich auch in ihrer abwechslungsrei- Die Preisträgerin internationaler Wettbewerbe ar- Christine Hoock leitet die Internationale Johann- ment, dessen Tonhöhe und Klangfarbe seine innere chen Diskographie wieder. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Jae Cosmos Lee, Violin

“CELLISSIMO” PROGRAM NOTES By Jae Cosmos Lee, Violin Max Brush (1838 – 1920) At the urging of the beginning with a slow introduction, which is Cello virtuoso Robert Hausmann, the an example of Beethoven breaking off from German Romantic composer, Max Bruch the normal fast movement form, especially completed his op.47, Kol Nidrei (the in the last movement of an instrumental Aramaic phrase, which means All Vows, and work. Moreover, the entire third movement is the incantation that starts the Yom Kippur is in E major, which is the dominant key from service) in 1880 and publishing it a year later the original A major that the first movement in Berlin. Along with his first Violin is written in, which at the time was Concerto, this composition, originally for considered highly unconventional. The A Cello and Orchestra, is one of his most minor Scherzo, which comprises the second beloved and widely performed pieces. For movement, is in the parallel minor to the that reason, it led the German National opening movement's key, which can also be Socialist Party during the 1930's to assume considered Beethoven going against the that Bruch was of Jewish origin and banned grain of his Viennese contemporaries. his music until Germany's defeat in the Second World War. Fortunately, for Bruch, who was raised Protestant, and whose ancestors were not Jewish, his music Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) at age 57, survived the persecution and Kol Nidrei is earnestly contemplated retirement from still firmly planted in the canon of every composing after the premiere of his String cellist. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1983, Tanglewood

. ^ 5^^ mar9 E^ ^"l^Hifi imSSii^*^^ ' •H-.-..-. 1 '1 i 1^ «^^«i»^^^m^ ^ "^^^^^. Llii:^^^ %^?W. ^ltm-''^4 j;4W»HH|K,tf.''if :**.. .^l^^- ^-?«^g?^5?,^^^^ _ '^ ** '.' *^*'^V^ - 1 jV^^ii 5 '|>5|. * .««8W!g^4sMi^^ -\.J1L Majestic pine lined drives, rambling elegant mfenor h^^, meandering lawns and gardens, velvet green mountain *4%ta! canoeing ponds and Laurel Lake. Two -hundred acres of the and present tastefully mingled. Afulfillment of every vacation delight . executive conference fancy . and elegant home dream. A choice for a day ... a month . a year. Savor the cuisine, entertainment in the lounges, horseback, sleigh, and carriage rides, health spa, tennis, swimming, fishing, skiing, golf The great estate tradition is at your fingertips, and we await you graciously with information on how to be part of the Foxhollow experience. Foxhollow . an tver growing select family. Offerings in: Vacation Homes, Time- Shared Villas, Conference Center. Route 7, Lenox, Massachusetts 01240 413-637-2000 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor One Hundred and Second Season, 1982-83 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Abram T. Collier, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Leo L. Beranek, Vice-President George H. Kidder, Vice-President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick William J. Poorvu J. P. Barger Mrs. John L. Grandin Irving W. Rabb Mrs. John M. Bradley David G. Mugar Mrs. George R. Rowland Mrs. Norman L. Cahners Albert L. Nickerson Mrs. George Lee Sargent George H.A. -

Charles Villiers Stanford(1852-1924)

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) SOMMCD 0185 String Quartet No. 3 in D minor, Op. 64 Céleste Series String Quartet No. 4 in G minor, Op. 99 String Quartet No. 7 in C minor, Op. 166 Charles Villiers (First Recordings) Stanford Dante Quartet Krysia Osostowicz & Oscar Perks violins Yuko Inoue viola, Richard Jenkinson cello String Quartet No. 3 [26:41] String Quartet No. 7 [21:13] n 1 1. Allegro moderato ma appassionato 6:05 9 1. Allegretto ma con fuoco 7:26 String Quartets 2 2. Allegretto semplice 5:40 bl 2. Andante 6:57 3 3. Andante (quasi Fantasia) 7:54 bm 3. Allegro molto 3:31 Nos 3, 4 & 7 4 4. Allegro feroce ma non troppo mosso 7:01 bn 4. Allegro giusto 3:18 String Quartet No. 4 [27:57] n 5 1. Allegro moderato 9:46 6 2. Allegretto vivace 4:18 7 3. Adagio 7:08 First Recordings 8 4. Allegro molto vivace 6:44 Total recording time 76:09 Recorded at St. Nicholas Parish Church, Thames Ditton. Nos. 3 & 4: June 22-23, 2017; No. 7: May 8, 2018 Producer: Siva Oke Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor ante Front cover: Psyche Entering Cupid’s Garden by JW Waterhouse (1849-1917) D © Harris Museum & Art Gallery, Preston / Bridgeman Images Design: Andrew Giles Booklet Editor: Michael Quinn Quartet DDD © & 2018 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU Charles Villiers from the examples of the 19th-century German canon (and especially the three Stanford quartets of Brahms) and which he passed onto his pupils such as Vaughan Williams, Bridge, Dyson and Howells. -

(Of(R) Viola) and Piano Op

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: November 18, 2004 I, Kyung ju Lee _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Viola Performance It is entitled: An analysis and comparison of the clarinet and viola versions of the Two sonatas for clarinet (or Viola) And piano Op.120 by Johannes Brahms. This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Catharine Carroll Lee Fiser Steven Cohen 2 AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF THE CLARINET AND VIOLA VERSION OF THE TWO SONATAS FOR CLARINET (OR VIOLA) AND PIANO OP. 120 BY JOHANNES BRAHMS. A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2004 by Kyungju Lee B.M., Yeungnam University, 1996 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 A.D., University of Cincinnati, 2002 Committee Chair: Catharine Carroll, D.M.A. 2 3 ABSTRACT Johannes Brahms was one of the first composers to appreciate fully the viola’s potential, allowing the instrument a chance to shine in his chamber music. Although Brahms’ Two Sonatas in f-minor and E-flat major, Op.120, were originally written for clarinet and piano, they are also greatly loved in the viola repertoire. Upon examination of the clarinet and viola versions of the sonatas, Brahms seems to have been keenly aware of the potential of each instrument. He intentionally sought different effects from these two instruments by composing two different versions. -

David Shifrin August 8

Carte Blanche Concert III: David Shifrin August 8 Monday, August 8 JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, op. 120, no. 1 (1894) Allegro appassionato Andante un poco adagio PROgram OVERVIEW Allegretto grazioso ERTS Clarinetist David Shifrin makes his Music@Menlo debut with Vivace C a program illustrating the autumnal quality of Brahms’s late David Shifrin, clarinet; Jon Kimura Parker, piano works. As a complement to the fes tival’s “Farewell” program (see p. 27), the season’s third Carte Blanche Concert cen- JOHANNES BrahmS ON ters on Brahms’s discovery of the clarinet at the end of his Clarinet Trio in a minor, op. 114 (1891) C life. Along side the immortal Clarinet Quintet offered on Con- Allegro Adagio cert Program VI, Brahms’s f minor Clarinet Sonata and the Andante grazioso HE Clarinet Trio reveal the composer at his most introspective. Allegro Max Bruch’s Pieces for Clarinet Trio, composed more than a C Intermission decade after Brahms’s death, evoke Brahms in their pathos N and deeply felt lyricism. A MAX BRUCH (1838–1920) L From Eight Pieces, op. 83 (1909) Nachtgesang (Nocturne): Andante con moto B Allegro con moto SPECIAL THANKS Andante con moto Music@Menlo dedicates this performance to Michèle and Allegro vivace, ma non troppo Larry Corash with gratitude for their generous support. David Shifrin, clarinet; Wu Han, piano; David Finckel, cello RTE CA www.musicatmenlo.org CARTE BLANCHE CONCERTS Program Notes: David Shifrin JOHANNES BRAHMS trio favors restraint over Sturm und Drang, calling to mind Brahms’s (Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg; died April 3, 1897, Vienna) other great a minor chamber work, the Opus 51 Number 2 String Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, op. -

Gould Piano Trio

SANIBEL MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAM NOTES GOULD PIANO TRIO Lucy Gould, violin ~ Richard Lester, cello ~ Benjamin Frith, piano with ROBERT PLANE, clarinet Saturday, March 21, 2019 ~ PROGRAM ~ Trio for Clarinet, Cello Johannes BRAHMS And Piano in A minor, Op. 114 (1833-1897) Allegro Adagio Andantino grazioso Allegro Four Fables for Clarinet, Violin, Huw WATKINS Cello, and Piano (b. 1976) Lento Allegro Lento Lento — Andante — Allegro ~ INTERMISSION ~ Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello Antonín DVOŘÁK in F minor, Op. 65 (1841-1904) Allegro ma non troppo Allegretto grazioso Poco adagio Allegro con brio Gould Piano Trio The Gould Piano Trio, which was compared by the Washington Post to the great Beaux Arts Trio for its “musical fire” and “dedication to the genre,” has remained at the forefront of the international chamber music scene for a quarter of a century. Launched by their First Prize at the Melbourne Chamber Music Competition and subsequently selected as “Rising Stars” by Britain’s Young Concert Artists Trust Artists, the ensemble made a highly successful debut at New York’s Weill Recital Hall that was described by Strad Magazine as “Pure Gould.” The Trio’s many appearances at London’s Wigmore Hall have included the complete piano trios of Dvořák, Mendelssohn, and Schubert, plus a Beethoven cycle in 2017-2018 to celebrate the ensemble’s 25th anniversary appearing at that iconic venue. Commissioning and performing new works is an important part of the Gould Trio’s philosophy of remaining creative inspired. Most recently, the Trio premiered Four Fables by Huw Watkins, one of today’s most popular British composers, who was featured at Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center this past season. -

Marshall University Department of Music Presents a Senior Recital Dean Pauley, Cello, Alanna Cushing, Piano Dean Pauley Marshall University

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar All Performances Performance Collection Spring 4-9-2012 Marshall University Department of Music presents a Senior Recital Dean Pauley, cello, Alanna Cushing, piano Dean Pauley Marshall University Alanna Cushing Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Pauley, Dean and Cushing, Alanna, "Marshall University Department of Music presents a Senior Recital Dean Pauley, cello, Alanna Cushing, piano" (2012). All Performances. Book 49. http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf/49 This Recital is brought to you for free and open access by the Performance Collection at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Performances by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEPARTMENT of MUSIC Program Trio for Clarinet, Cello, and Piano, Op. 114 Johannes Brahms (1833 - 1897) Allegro Adagio presents a Emily Hall, clarinet Dean Pauley, cello Dr. Henning Vauth, piano Senior Recital Dean Pauley, cello Sonata for Cello and Piano in D Minor Claude Debussy (1862 - 1918) Alanna Cushing, piano I. Prologue: Lent, sostenuto e molto risoluto II. Sérénade: Modérément animé in collaboration with guest artists III. Final: Animé, léger et nerveux Dr. Henning Vauth, piano Emily Hall, clarinet Brief Intermission Suite for Unaccompanied Cello Johann Sebastian Bach in D Minor BWV 1008 (1685 – 1750) Monday, April 9, 2012 Prelude Smith Recital Hall Sarabande 8:00pm Drei Fantasiestücke for Cello and Piano, Op. 73 Robert Schumann This program is presented by the College of Fine Arts through the (1810 – 1856) Department of Music, with the support of student activity funds.